Journal of Southern Medical University ›› 2026, Vol. 46 ›› Issue (1): 34-46.doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2026.01.04

Previous Articles Next Articles

Yue ZHANG1,2( ), Yuting DUAN1(

), Yuting DUAN1( ), Chen ZHANG1, Luzhe YU1, Yingying LIU1, Lihua XING1,3, Lei WANG1,3,5, Nianjun YU1, Daiyin PENG1,3,4,5, Weidong CHEN1,3,4,5(

), Chen ZHANG1, Luzhe YU1, Yingying LIU1, Lihua XING1,3, Lei WANG1,3,5, Nianjun YU1, Daiyin PENG1,3,4,5, Weidong CHEN1,3,4,5( ), Yanyan WANG1,3,4(

), Yanyan WANG1,3,4( )

)

Received:2025-07-11

Online:2026-01-20

Published:2026-01-16

Contact:

Weidong CHEN, Yanyan WANG

E-mail:zhangyue@ahtcm.edu.cn;wdchen@ahtcm.edu.cn;wangyanyan@ahtcm.edu.cn

Supported by:Yue ZHANG, Yuting DUAN, Chen ZHANG, Luzhe YU, Yingying LIU, Lihua XING, Lei WANG, Nianjun YU, Daiyin PENG, Weidong CHEN, Yanyan WANG. Poria cocos polysaccharide alleviates cyclophosphamide-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and inflammation in mice by modulating gut flora[J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2026, 46(1): 34-46.

Add to citation manager EndNote|Ris|BibTeX

URL: https://www.j-smu.com/EN/10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2026.01.04

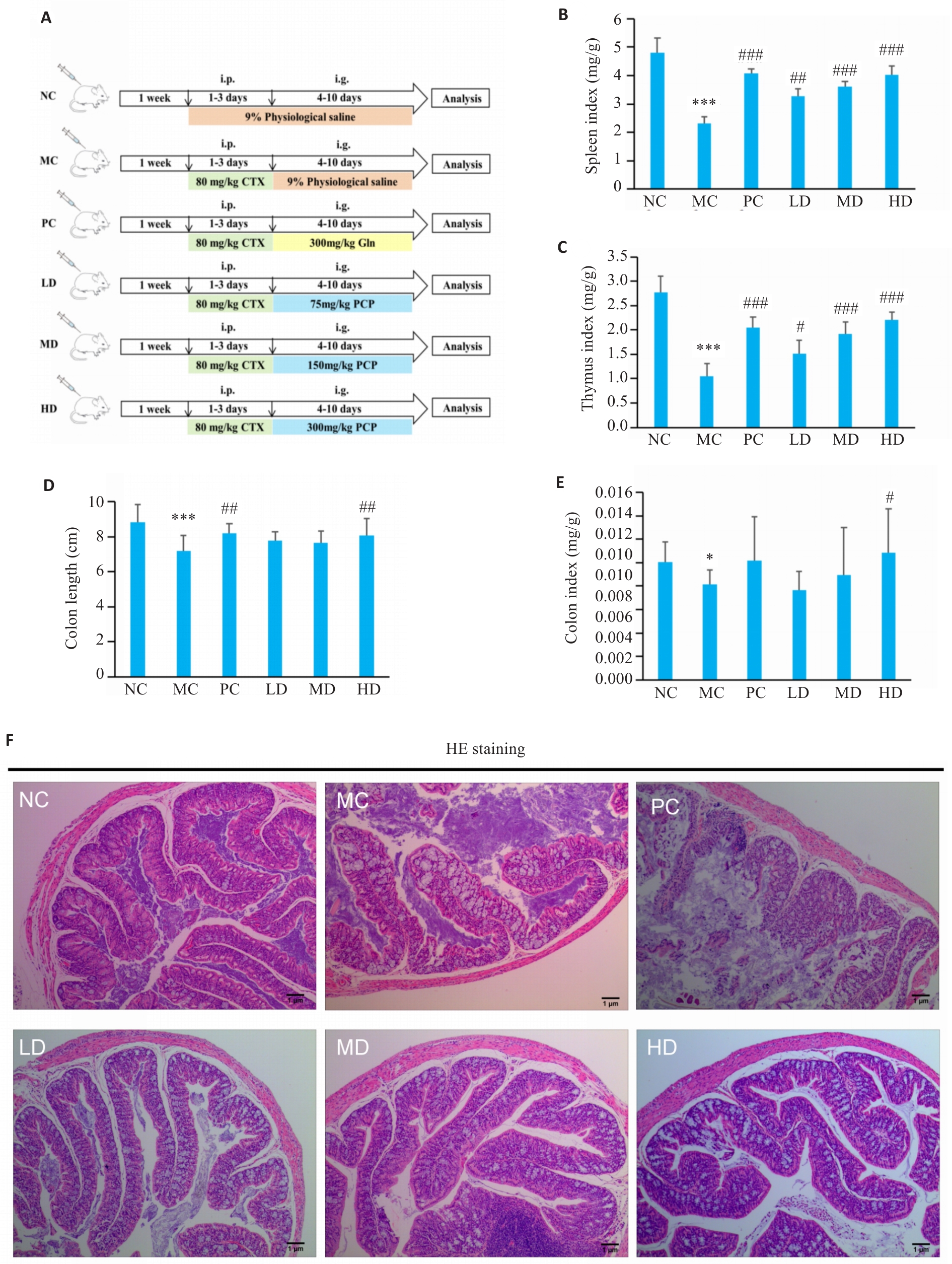

Fig.1 Effect of PCP on physiological state of the colon in CTX-treated mice. A: Illustration of the experiment design. i.p.:Intraperitoneal injection,i.g.: Irrigation. B: Spleen index (spleen weight/body weight). C: Thymus index (thymus weight/body weight) of the mice. D: Colon length of the mice. E: Colon index (colon weight/body weight). F: HE staining of the colon tissue (Original magnification: ×7.5). NC: Control group; MC: CTX model group; PC: CTX+Glutamine (positive drug) group; LD: CTX+PCP low dose group; MD: CTX+PCP medium dose group; HD: CTX+PCP high dose group. Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs NC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs MC group.

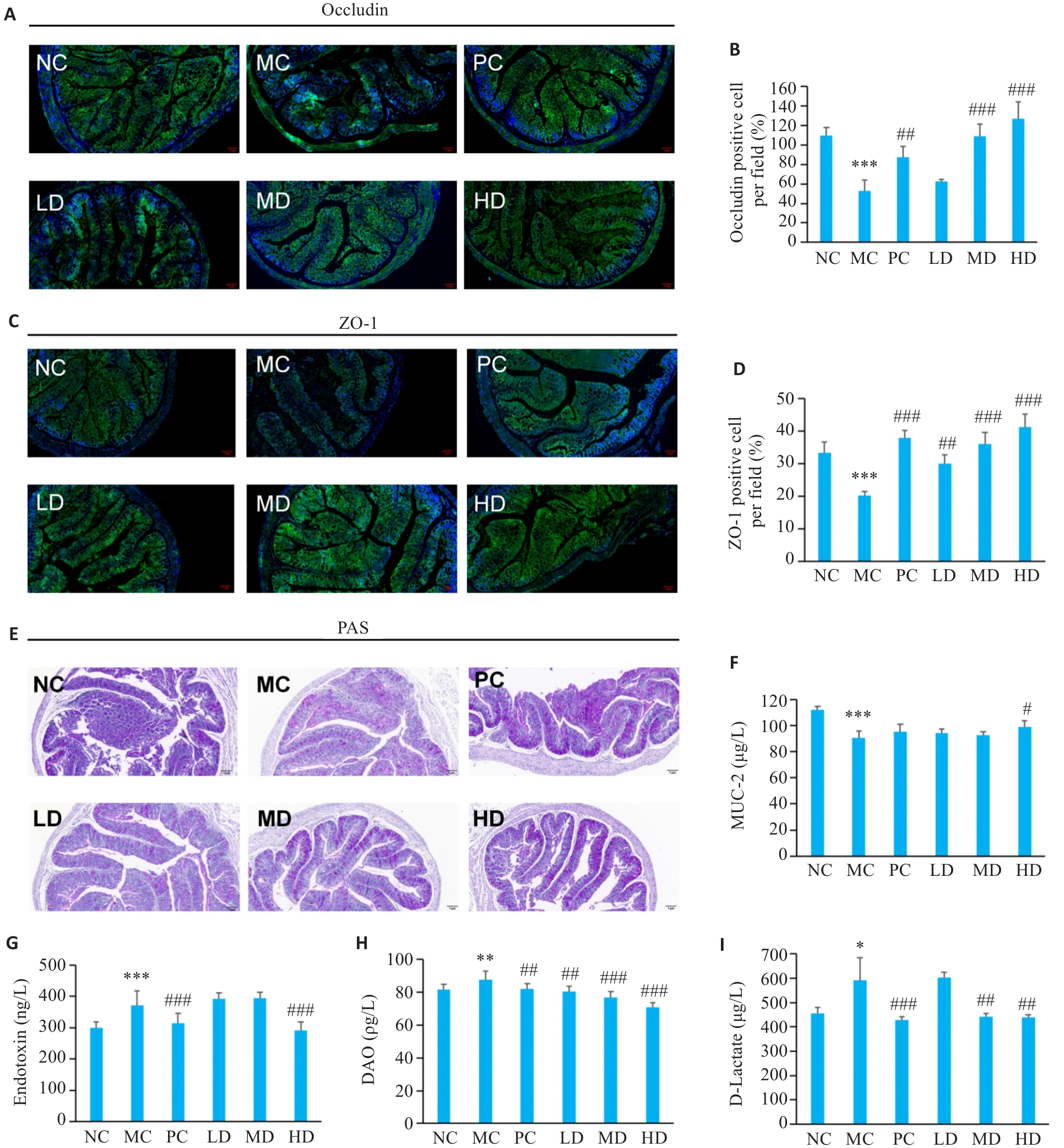

Fig.2 Effect of PCP on intestinal barrier function in CTX-treated mice. A-D: Immunofluorescence staining of occludin and ZO-1 (green: occludin and ZO-1; blue: nucleus; ×7.5). E: PAS staining showing mucus-secreting epithelial cells (×7.5). F: MUC2 contents in colonic tissues. G: Endotoxin levels in serum. H: DAO levels in serum. I: D-Lactate levels in serum. Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs MC group.

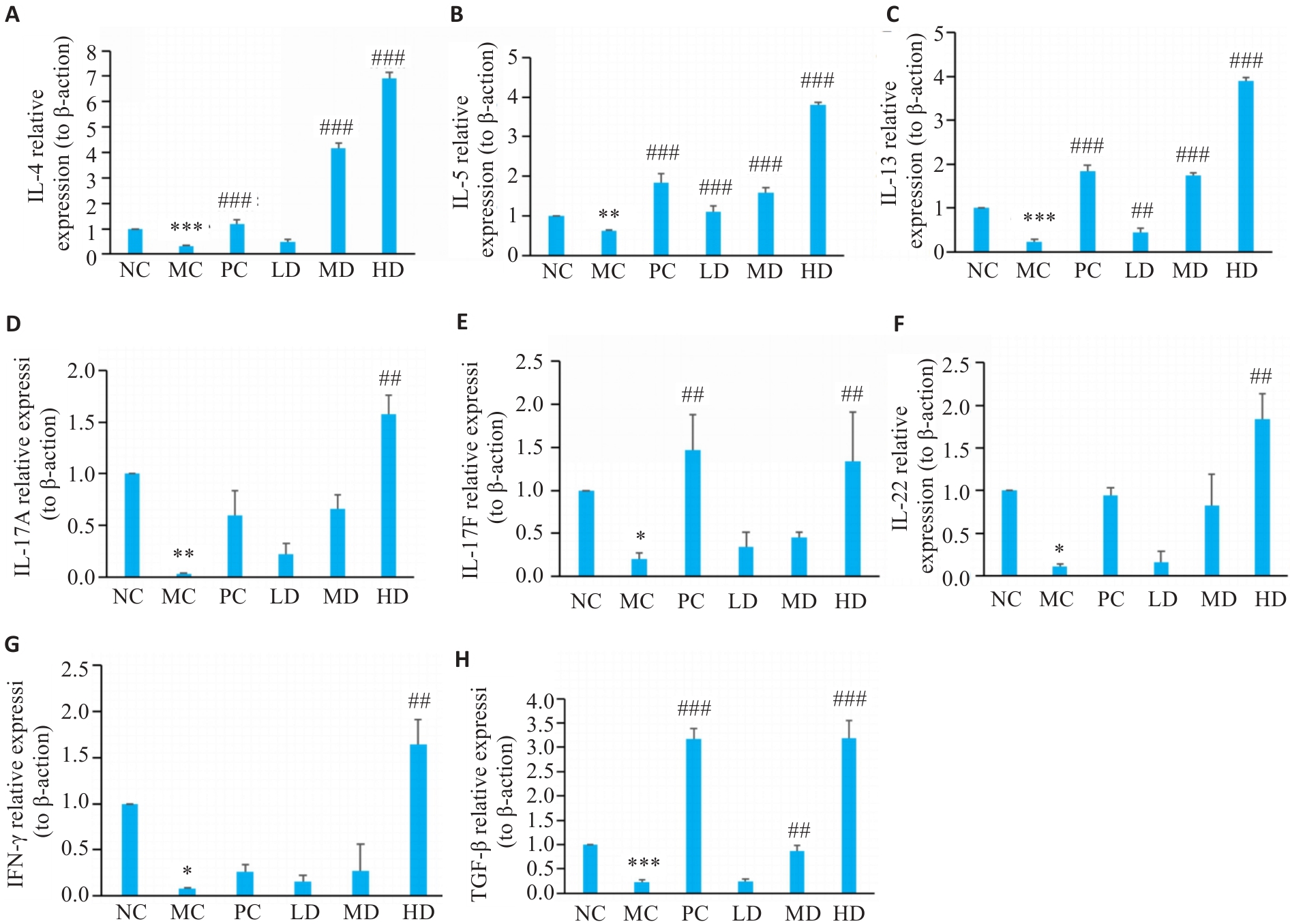

Fig.3 Effect of PCP on immune cytokines in the colonic mucosa of the mice. A-H: Relative mRNA expression levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IFN-γ, and TGF-β detected with RT-qPCR, using β-actin as the reference control. Data are represented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NC group; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs MC group.

| Group | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson | Goods_coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 195.22±50.78 | 195.79±51.02 | 5.81±0.21 | 0.97±0.00 | 1.00 |

| MC | 182.98±17.05 | 183.05±16.94 | 5.51±0.23 | 0.96±0.01 | 1.00 |

| HD | 275.21±52.61 | 274.09±51.86 | 6.32±0.44 | 0.98±0.01 | 1.00 |

Tab.1 Diversity indexes of gut microbiota in NC, MC, and HD groups (Mean±SD, n=6)

| Group | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson | Goods_coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 195.22±50.78 | 195.79±51.02 | 5.81±0.21 | 0.97±0.00 | 1.00 |

| MC | 182.98±17.05 | 183.05±16.94 | 5.51±0.23 | 0.96±0.01 | 1.00 |

| HD | 275.21±52.61 | 274.09±51.86 | 6.32±0.44 | 0.98±0.01 | 1.00 |

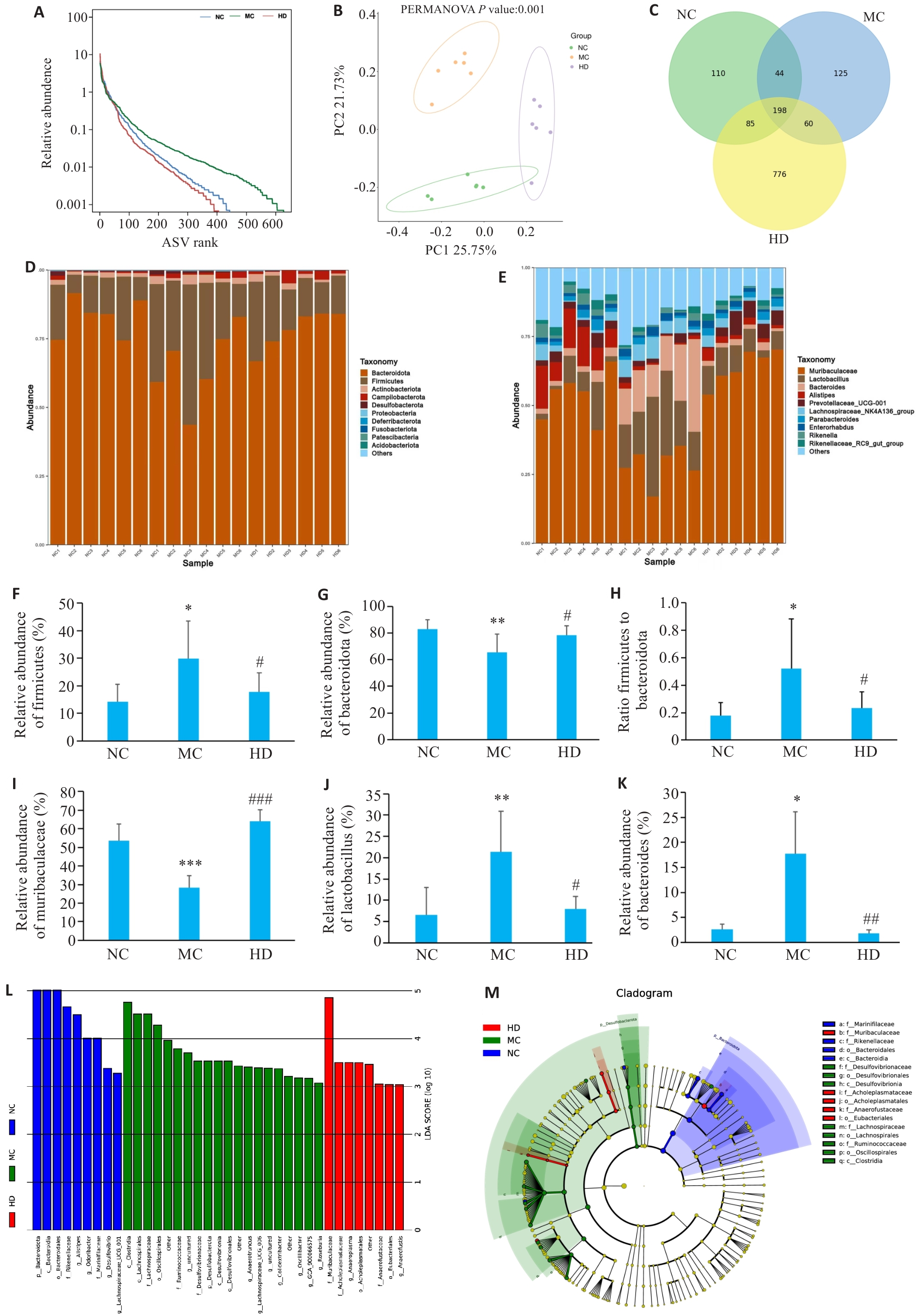

Fig.4 Effect of PCP on gut microbiota composition in CTX-treated mice. A: Species abundance distribution curve. B: Principal coordinates analysis. C: Venn graph showing species overlap. D: Phylum-level microbial composition. E: Genus-level microbial composition. F: Firmicutes abundance. G: Bacteroidetes abundance. H: Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio. I: Muribaculaceae abundance. J: Lactobacillus abundance. K: Bacteroides abundance. L: LDA score. M: Phylogenetic distribution of discriminant taxa. Data are represented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs MC group.

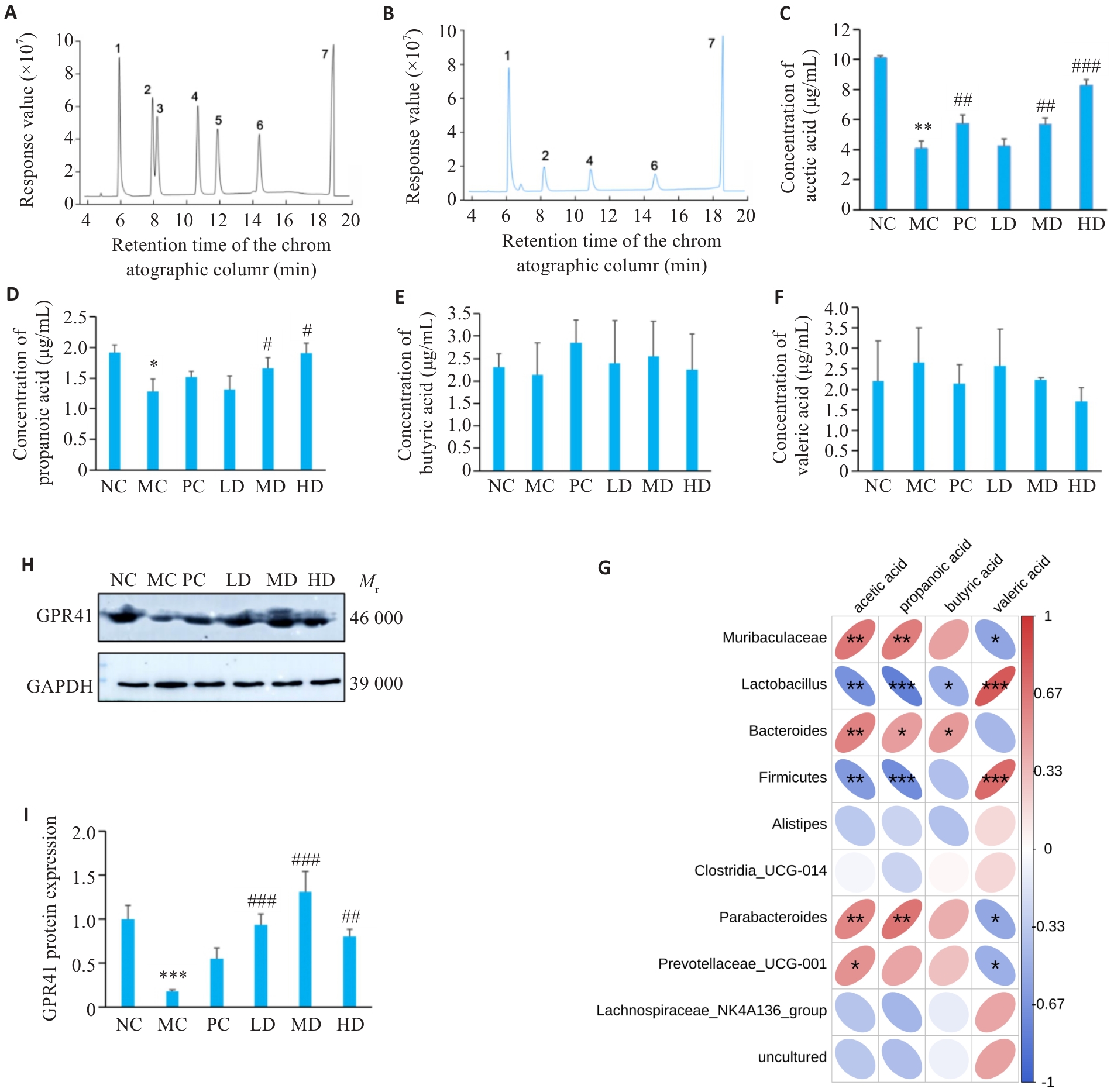

Fig.5 Effect of PCP on SCFAs content in CTX-treated mice. A: Standard curve of each component of SCFAs to be measured. B: GC chromatogram of mixed control solution of SCFAs (1: acetic acid; 2: propionic acid; 3: butyric acid; 4: isobutyric acid; 5: valeric acid; 6: isovaleric acid; 7: 2-ethylbutyric acid). C: Acetate levels. D: Propionate levels. E: Butyrate levels. F: Valerate levels. G: Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. H: Representative bands of GPR41. I: Protein expression of GPR41. Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs MC group.

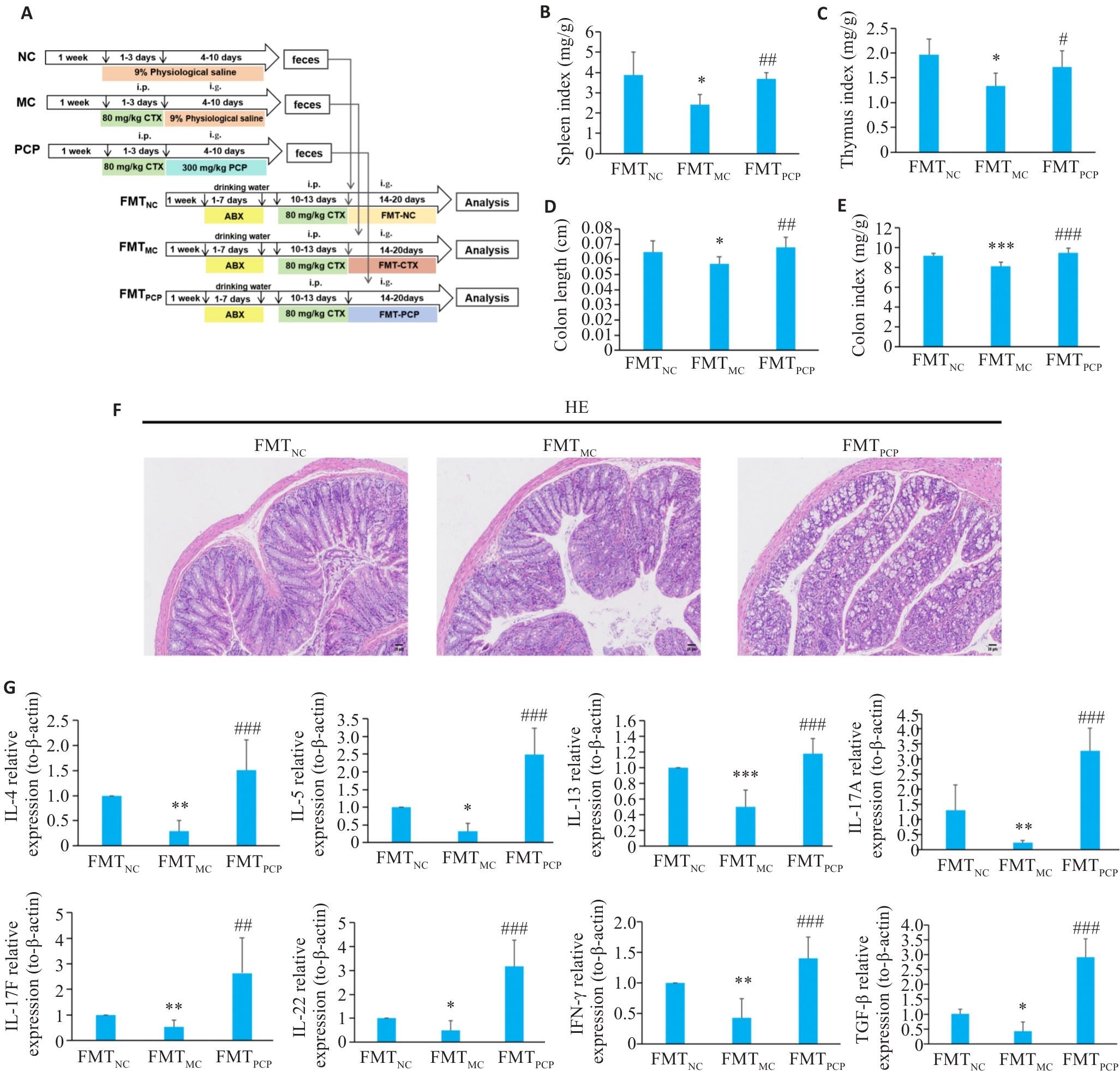

Fig.6 Effect of FMT on colon injury in CTX-treated mice. A: Illustration of the design of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiment. B: Splenic somatic index (organ-to-body weight ratio). C: Thymus index (thymus weight/body weight). D: Colon length. E: Colon index (colon weight/body weight). F: HE staining (×100). FMTNC: FMT normal group; FMTCTX: FMT CTX model group; FMTPCP: FMT-Poria cocos polysaccharide. G: FMT modulates immune function in CTX-treated mice (Relative mRNA expression levels of cytokines: IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IFN-γ, and TGF-β). Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs FMTNC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs FMTMC group.

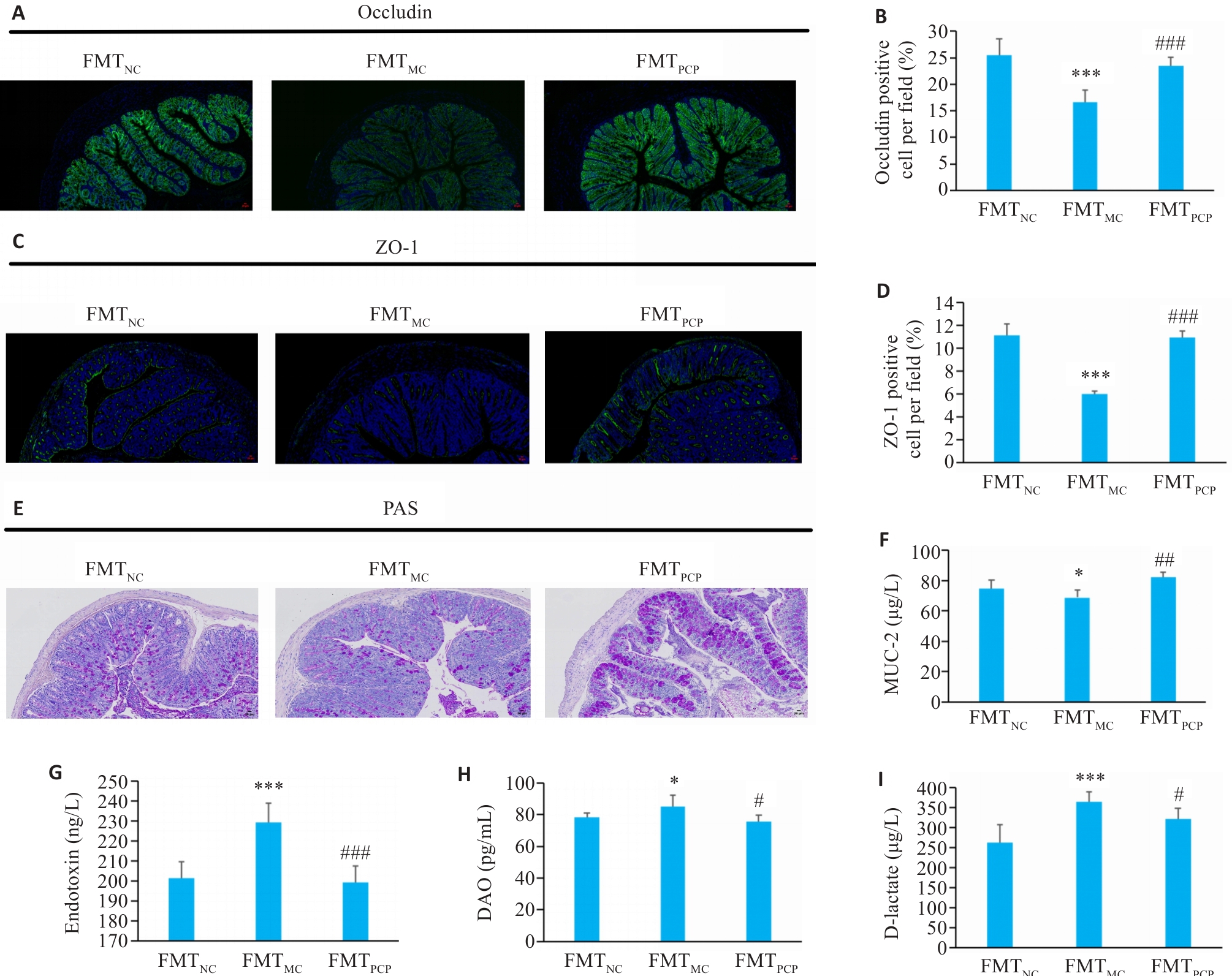

Fig.7 Effect of FMT on intestinal permeability of the mice. A-D: Immunofluorescence staining of occludin and ZO-1. (green: Occludin and ZO-1; blue: nucleus; ×100). E: PAS staining showing mucus-secreting epithelial cells (×100). F: MUC2 content in colonic tissue. G: Endotoxin levels in serum. H: DAO levels in serum. I: D-Lactate levels in serum. Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs FMTNC group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs FMTMC group.

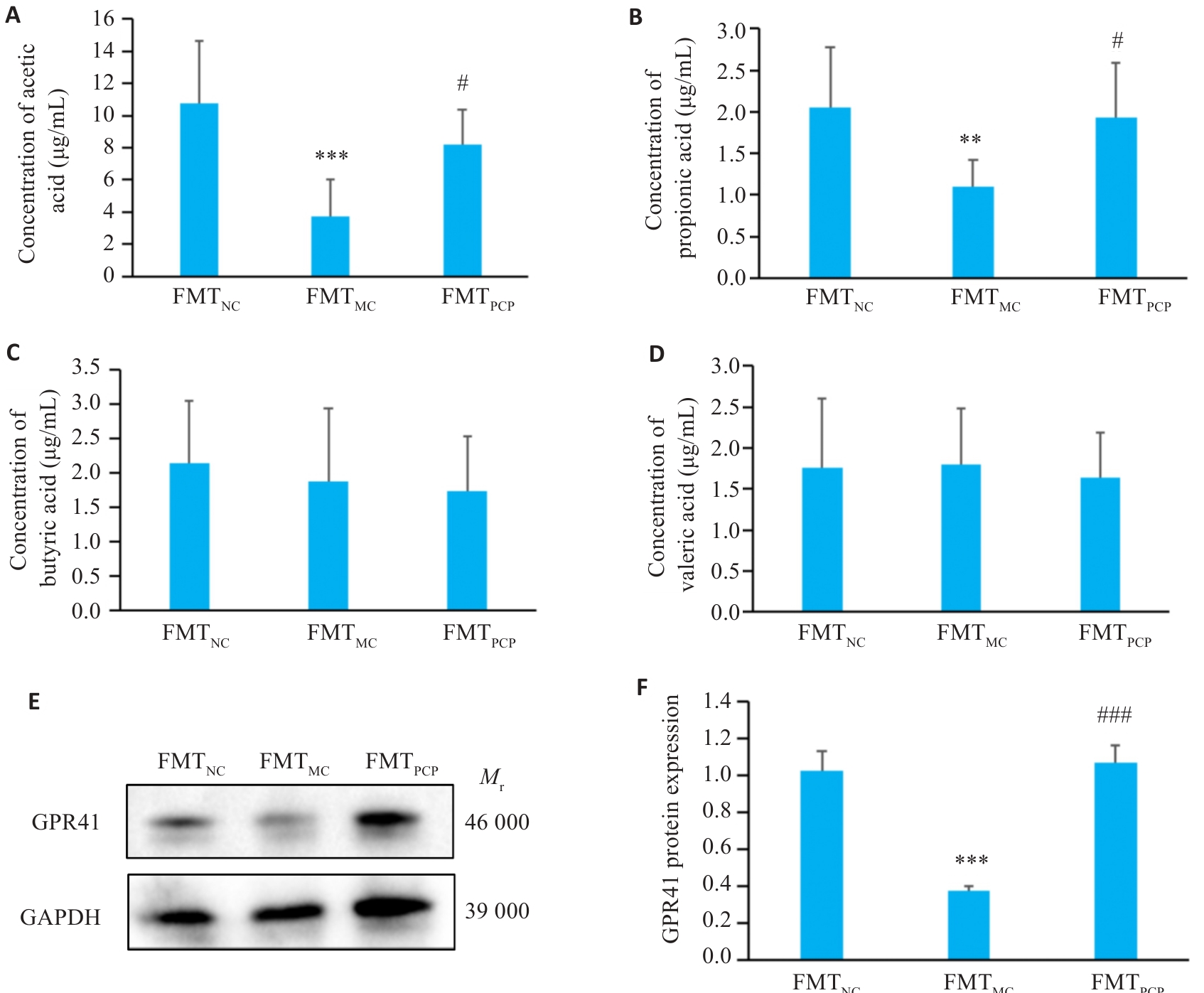

Fig. 8 Effect of FMT on SCFAs content and GPR41 in the colon of the mice. A: Acetate. B: Propionate. C: Butyrate. D: Valerate concentrations. E: Representative bands of GPR41. F: Quantitative analysis of GPR41 protein expression normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as Mean±SD (n=6). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs FMTNC group; #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 vs FMTMC group.

| [1] | Chu Q, Zhang YR, Chen W, et al. Apios americana Medik flowers polysaccharide (AFP) alleviate Cyclophosphamide-induced imm-unosuppression in ICR mice[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2020, 144: 829-36. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.035 |

| [2] | Day W, Gabriel C, Kelly RE, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis resembling late-stage Degos disease with gastrointestinal perfo-rations successfully treated with combination of cyclophosphamide and rituximab: case-based review[J]. Rheumatol Int, 2020, 40(11): 1883-90. doi:10.1007/s00296-019-04495-2 |

| [3] | Viaud S, Saccheri F, Mignot G, et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide[J]. Science, 2013, 342(6161): 971-6. doi:10.1126/science.1240537 |

| [4] | Allaire JM, Crowley SM, Law HT, et al. The intestinal epithelium: central coordinator of mucosal immunity[J]. Trends Immunol, 2018, 39(9): 677-96. doi:10.1016/j.it.2018.04.002 |

| [5] | Chistiakov DA, Bobryshev YV, Kozarov E, et al. Intestinal mucosal tolerance and impact of gut microbiota to mucosal tolerance[J]. Front Microbiol, 2015, 5: 781. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00781 |

| [6] | Cani PD, Possemiers S, Van de Wiele T, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability[J]. Gut, 2009, 58(8): 1091-103. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.165886 |

| [7] | Yang WJ, Yu TM, Huang XS, et al. Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 4457. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18262-6 |

| [8] | Kayama H, Okumura R, Takeda K. Interaction between the microbiota, epithelia, and immune cells in the intestine[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2020, 38: 23-48. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-070119-115104 |

| [9] | 聂文律, 王东鹏, 钟丽姣, 等. 麸炒苍术精制多糖通过调节亚油酸代谢改善环磷酰胺诱导的小鼠免疫抑制与肠道损伤[J/OL].中国中药杂志,1-14 [2025-10-15]. . |

| [10] | 郭林霞, 马可为, 冯志华, 等. 枣多糖提取物对环磷酰胺所致的蛋雏鸡肠黏膜免疫屏障功能下降的缓解作用[J]. 中国兽医学报, 2022, 42(1): 107-13. |

| [11] | Xu TR, Zhang HM, Wang SG, et al. A review on the advances in the extraction methods and structure elucidation of Poria cocos polysaccharide and its pharmacological activities and drug carrier applications[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2022, 217: 536-51. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.07.070 |

| [12] | Zhao MH, Guan ZY, Tang N, et al. The differences between the water- and alkaline-soluble Poria cocos polysaccharide: a review[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2023, 235: 123925. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123925 |

| [13] | Jiang YH, Wang L, Chen WD, et al. Poria cocos polysaccharide prevents alcohol-induced hepatic injury and inflammation by repressing oxidative stress and gut leakiness[J]. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 963598. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.963598 |

| [14] | Duan YT, Huang JJ, Sun MJ, et al. Poria cocos polysaccharide improves intestinal barrier function and maintains intestinal homeostasis in mice[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2023, 249: 125953. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125953 |

| [15] | Sun MJ, Yao L, Yu QM, et al. Screening of Poria cocos polysaccharide with immunomodulatory activity and its activation effects on TLR4/MD2/NF-κB pathway[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2024, 273(Pt 1): 132931. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132931 |

| [16] | 房 悦, 黄佳静, 张 越, 等. 基于BTLA/HVEM通路研究茯苓多糖对免疫抑制小鼠的免疫调节作用[J]. 中南药学, 2025, 23(5): 1183-9. |

| [17] | 王灿红, 霍小位, 何晓山, 等. 羧甲基茯苓多糖对肠癌小鼠生命延长及对环磷酰胺的减毒作用[J]. 食品科学, 2016, 37(21): 229-33. |

| [18] | Cheng Y, Xie Y, Ge JC, et al. Structural characterization and hepatoprotective activity of a galactoglucan from Poria cocos [J]. Carbohydr Polym, 2021, 263: 117979. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117979 |

| [19] | Wang J, Li MH, Gao YW, et al. Effects of exopolysaccharides from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum JLAU103 on intestinal immune response, oxidative stress, and microbial communities in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2022, 70(7): 2197-210. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c06502 |

| [20] | Wu ZH, Huang SM, Li TT, et al. Gut microbiota from green tea polyphenol-dosed mice improves intestinal epithelial homeostasis and ameliorates experimental colitis[J]. Microbiome, 2021, 9(1): 184. doi:10.1186/s40168-021-01115-9 |

| [21] | Chang CJ, Lin CS, Lu CC, et al. Ganoderma lucidum reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota[J]. Nat Commun, 2015, 6: 7489. doi:10.1038/ncomms8489 |

| [22] | Jädert C, Phillipson M, Holm L, et al. Preventive and therapeutic effects of nitrite supplementation in experimental inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Redox Biol, 2013, 2: 73-81. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.012 |

| [23] | Mao XM, Wu S, Huang DD, et al. Complications and comorbidities associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy: Rethinking drug design and delivery for anticancer therapy[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2024, 14(7): 2901-26. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2024.03.006 |

| [24] | Chen L, Wang D, Liu W, et al. Immunomodulation of exopo-lysaccharide produced by Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ZFM216 in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice by modulating gut microbiota[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2024, 283(Pt 2): 137619. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137619 |

| [25] | Xue HK, Liang BM, Wang Y, et al. The regulatory effect of polysaccharides on the gut microbiota and their effect on human health: a review[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2024, 270(Pt 2): 132170. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132170 |

| [26] | Ying MX, Yu Q, Zheng B, et al. Cultured Cordyceps sinensis polysaccharides modulate intestinal mucosal immunity and gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-treated mice[J]. Carbohydr Polym, 2020, 235: 115957. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115957 |

| [27] | Zhu ZP, Luo YR, Lin LT, et al. Modulating effects of turmeric polysaccharides on immune response and gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-treated mice[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2024, 72(7): 3469-82. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c05590 |

| [28] | Li N, Wang D, Wen XJ, et al. Effects of polysaccharides from Gastrodia elata on the immunomodulatory activity and gut microbiota regulation in cyclophosphamide-treated mice[J]. J Sci Food Agric, 2023, 103(7): 3390-401. doi:10.1002/jsfa.12491 |

| [29] | Wang DP, Dong Y, Xie Y, et al. Atractylodes lancea rhizome polysaccharide alleviates immunosuppression and intestinal mucosal injury in mice treated with cyclophosphamide[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2023. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c05173 |

| [30] | Chopyk DM, Grakoui A. Contribution of the intestinal microbiome and gut barrier to hepatic disorders[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 159(3): 849-63. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.077 |

| [31] | Buckley A, Turner JR. Cell biology of tight junction barrier regulation and mucosal disease[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2018, 10(1): a029314. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a029314 |

| [32] | Nyström EEL, Martinez-Abad B, Arike L, et al. An intercrypt subpopulation of goblet cells is essential for colonic mucus barrier function[J]. Science, 2021, 372(6539): eabb1590. doi:10.1126/science.abb1590 |

| [33] | Gustafsson JK, Johansson MEV. The role of goblet cells and mucus in intestinal homeostasis[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 19(12): 785-803. doi:10.1038/s41575-022-00675-x |

| [34] | Pizarro TT, Dinarello CA, Cominelli F. Editorial: cytokines and intestinal mucosal immunity[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 698693. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.698693 |

| [35] | Wu XC, Huang XJ, Ma WN, et al. Bioactive polysaccharides promote gut immunity via different ways[J]. Food Funct, 2023, 14(3): 1387-400. doi:10.1039/d2fo03181g |

| [36] | Knox NC, Forbes JD, Peterson CL, et al. The gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: lessons learned from other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2019, 114(7): 1051-70. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000305 |

| [37] | Fu YP, Feng B, Zhu ZK, et al. The polysaccharides from Codonopsis pilosula modulates the immunity and intestinal microbiota of cyclophosphamide-treated immunosuppressed mice[J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(7): 1801. doi:10.3390/molecules23071801 |

| [38] | Zhu YQ, Chen BR, Zhang XY, et al. Exploration of the Muribaculaceae family in the gut microbiota: diversity, metabolism, and function[J]. Nutrients, 2024, 16(16): 2660. doi:10.3390/nu16162660 |

| [39] | Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status[J]. Cell, 2021, 184(16): 4137-53. e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019 |

| [40] | Han F, Wang Y, Han YY, et al. Effects of whole-grain rice and wheat on composition of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in rats[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2018, 66(25): 6326-35. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01891 |

| [41] | Wang H, Li ML, Jiao FR, et al. Soluble dietary fibers from solid-state fermentation of wheat bran by the fungus Cordyceps cicadae and their effects on colitis mice[J]. Food Funct, 2024, 15(2): 516-29. doi:10.1039/d3fo03851c |

| [42] | de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, et al. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights[J]. Gut, 2022, 71(5): 1020-32. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326789 |

| [1] | Ruimin HAN, Manke ZHAO, Junfang YUAN, Zhenhong SHI, Zhen WANG, Defeng WANG. Live combined Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium improves glucose and lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetic mice with circadian rhythm disruption via the SCFAs/GPR43/GLP-1 pathway [J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2025, 45(7): 1490-1497. |

| [2] | XU Xinzhu, Lina GUO, Kangdi ZHENG, Yan MA, Shuxian LIN, Yingxi HE, Wen SHENG, Suhua XU, Feng QIU. Lacticaseibacillus paracasei E6 improves vinorelbine-induced immunosuppression in zebrafish through its metabolites acetic acid and propionic acid [J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2025, 45(2): 331-339. |

| [3] | Shuxian LIN, Lina GUO, Yan MA, Yao XIONG, Yingxi HE, Xinzhu XU, Wen SHENG, Suhua XU, Feng QIU. Lactobacillus plantarum ZG03 alleviates oxidative stress via its metabolites short-chain fatty acids [J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2025, 45(10): 2223-2230. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||