南方医科大学学报 ›› 2025, Vol. 45 ›› Issue (11): 2444-2455.doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2025.11.17

龚雪1( ), 樊雍扬2(

), 樊雍扬2( ), 罗开元2, 燕翼2, 李忠豪2(

), 罗开元2, 燕翼2, 李忠豪2( )

)

收稿日期:2025-04-03

出版日期:2025-11-20

发布日期:2025-11-28

通讯作者:

李忠豪

E-mail:503253172@qq.com;760445401@qq.com;525838244@qq.com

作者简介:龚 雪,本科,主管护师,E-mail: 503253172@qq.com基金资助:

Xue GONG1( ), Yongyang FAN2(

), Yongyang FAN2( ), Kaiyuan LUO2, Yi YAN2, Zhonghao LI2(

), Kaiyuan LUO2, Yi YAN2, Zhonghao LI2( )

)

Received:2025-04-03

Online:2025-11-20

Published:2025-11-28

Contact:

Zhonghao LI

E-mail:503253172@qq.com;760445401@qq.com;525838244@qq.com

Supported by:摘要:

目的 探讨人诱导多能干细胞衍生的心脏类器官在心脏疾病模型和药物评价中的潜在应用。 方法 通过调控Wnt信号通路构建由人诱导多能干细胞自组装衍生的心脏类器官,采用流式细胞术检测心脏类器官中心肌细胞比例,RT-qPCR检测干细胞标志基因(OCT4、Nanog、SOX2)和心肌细胞标志基因(TNNT2、NKX2.5、RYR2、KCNJ2)的表达,免疫荧光染色检测TNNT2、CD31、Vimentin的蛋白表达,钙瞬态检测心脏类器官跳动幅度;建立体外心肌损伤模型和缺血再灌注模型,Masson染色检测损伤水平,ELISA检测心肌肌钙蛋白T(cTnT)释放水平;利用TUNEL染色和钙瞬态检测分别评价化疗药物多柔比星和曲妥珠单抗对心脏类器官的毒副作用。 结果 心脏类器官在培养第8天开始跳动,心肌细胞在心脏类器官中占比为32.4%,心脏类器官可见心肌标志物TNNT2、NKX2.5、RYR2和KCNJ2大量表达(P<0.001)。不同批次分化的心脏类器官在形态大小、跳动频率、心肌细胞比例、和心肌收缩力方面均无显著差异。心脏类器官可维持体外培养≥50 d。液氮造成心脏类器官心肌损伤、 TNNT2和MYH7基因表达下降(P<0.05)、cTnT分泌增加(P<0.01)、跳动幅度下降(P<0.01)和峰值时间增加(P<0.01),而卡托普利处理可减轻损伤发生。低氧/复氧诱导心脏类器官缺血再灌注损伤,心肌纤维化和凋亡增多(P<0.001)。多柔比星处理心脏类器官24 h后,细胞死亡明显增加(P<0.05)、心脏类器官的跳动频率和细胞活力下降(P<0.05),且具有剂量依懒性。曲妥珠单抗引起心脏类器官收缩力和钙处理能力下降(P<0.05)。 结论 成功构建心脏类器官,并可用于心脏疾病建模及药物评价。

龚雪, 樊雍扬, 罗开元, 燕翼, 李忠豪. 利用人诱导多能干细胞构建的心脏类器官在心脏疾病建模及药物评价中的应用价值[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2025, 45(11): 2444-2455.

Xue GONG, Yongyang FAN, Kaiyuan LUO, Yi YAN, Zhonghao LI. Construction of cardiac organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for cardiac disease modeling and drug evaluation[J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2025, 45(11): 2444-2455.

| Gene | Forward Primer (5'→3') | Reverse Primer (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | CTCTGAGGTGTGGGGGATTC | TCAGGCTGAGAGGTCCCAAG |

| Nanog | TTTGTGGGCCTGAAGAAAACT | AGGGCTGTCCTGAATAAGCAG |

| SOX2 | GCCGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCG | GGCAGCGTGTACTTATCCTTCT |

| TNNT2 | GGAGGAGTCCAAACCAAAGCC | TCAAAGTCCACTCTCTCTCCATC |

| NKX2.5 | CCAAGTGTGCGTCTGCCTTT | CGCACAGCTCTTTCTTTTCGG |

| RYR2 | GGCAGCCCAAGGGTATCTC | ACACAGCGCCACCTTCATAAT |

| KCNJ2 | GTGCGAACCAACCGCTACA | CCAGCGAATGTCCACACAC |

| MYH7 | GGCAAGACAGTGACCGTGAAG | CGTAGCGATCCTTGAGGTTGTA |

| GAPDH | GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT | GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

表1 RT-qPCR引物序列

Tab.1 Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

| Gene | Forward Primer (5'→3') | Reverse Primer (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | CTCTGAGGTGTGGGGGATTC | TCAGGCTGAGAGGTCCCAAG |

| Nanog | TTTGTGGGCCTGAAGAAAACT | AGGGCTGTCCTGAATAAGCAG |

| SOX2 | GCCGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCG | GGCAGCGTGTACTTATCCTTCT |

| TNNT2 | GGAGGAGTCCAAACCAAAGCC | TCAAAGTCCACTCTCTCTCCATC |

| NKX2.5 | CCAAGTGTGCGTCTGCCTTT | CGCACAGCTCTTTCTTTTCGG |

| RYR2 | GGCAGCCCAAGGGTATCTC | ACACAGCGCCACCTTCATAAT |

| KCNJ2 | GTGCGAACCAACCGCTACA | CCAGCGAATGTCCACACAC |

| MYH7 | GGCAAGACAGTGACCGTGAAG | CGTAGCGATCCTTGAGGTTGTA |

| GAPDH | GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT | GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

图1 心脏类器官的构建

Fig.1 Construction of the Cardiac Organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. A: Schematic diagram depicting the protocol for constructing cardiac organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. B: Brightfield images of the developing cardiac organoids. C, D: Proportion of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells in cardiac organoids determined by flow cytometry. E: Frozen sections of the developing cardiac organoids. F: Diameter of the developing cardiac organoids (n=10). G: The mRNA expressions in cardiac organoids determined by RT-qPCR. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs D0.

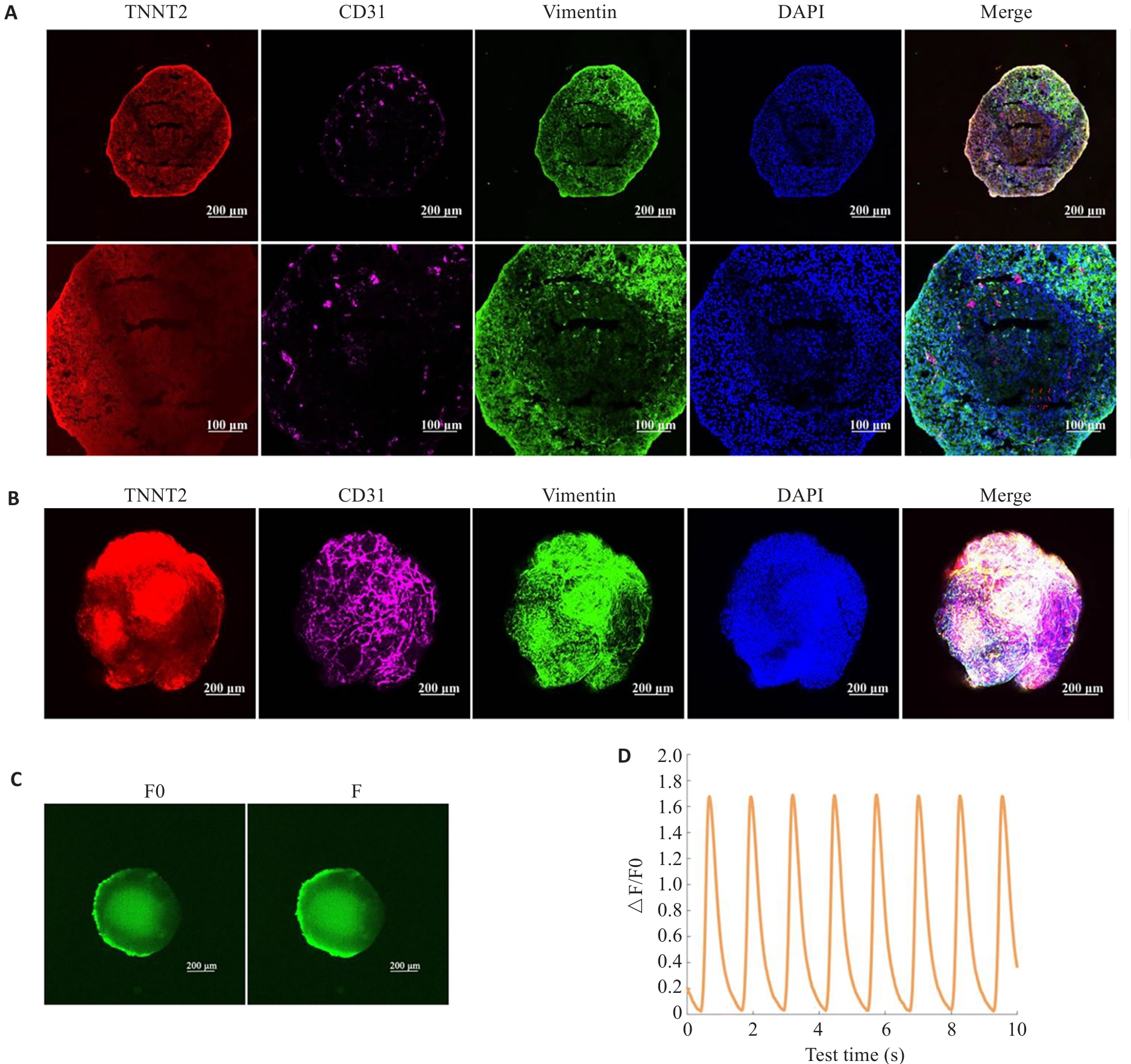

图2 心脏类器官的鉴定

Fig.2 Characterization of the constructed cardiac organoids. A: Immunofluorescent staining of frozen sections of the cardiac organoids. B: Whole-mount staining of the cardiac organoids. C, D: Calcium transient assay of the cardiac organoids (n=3).

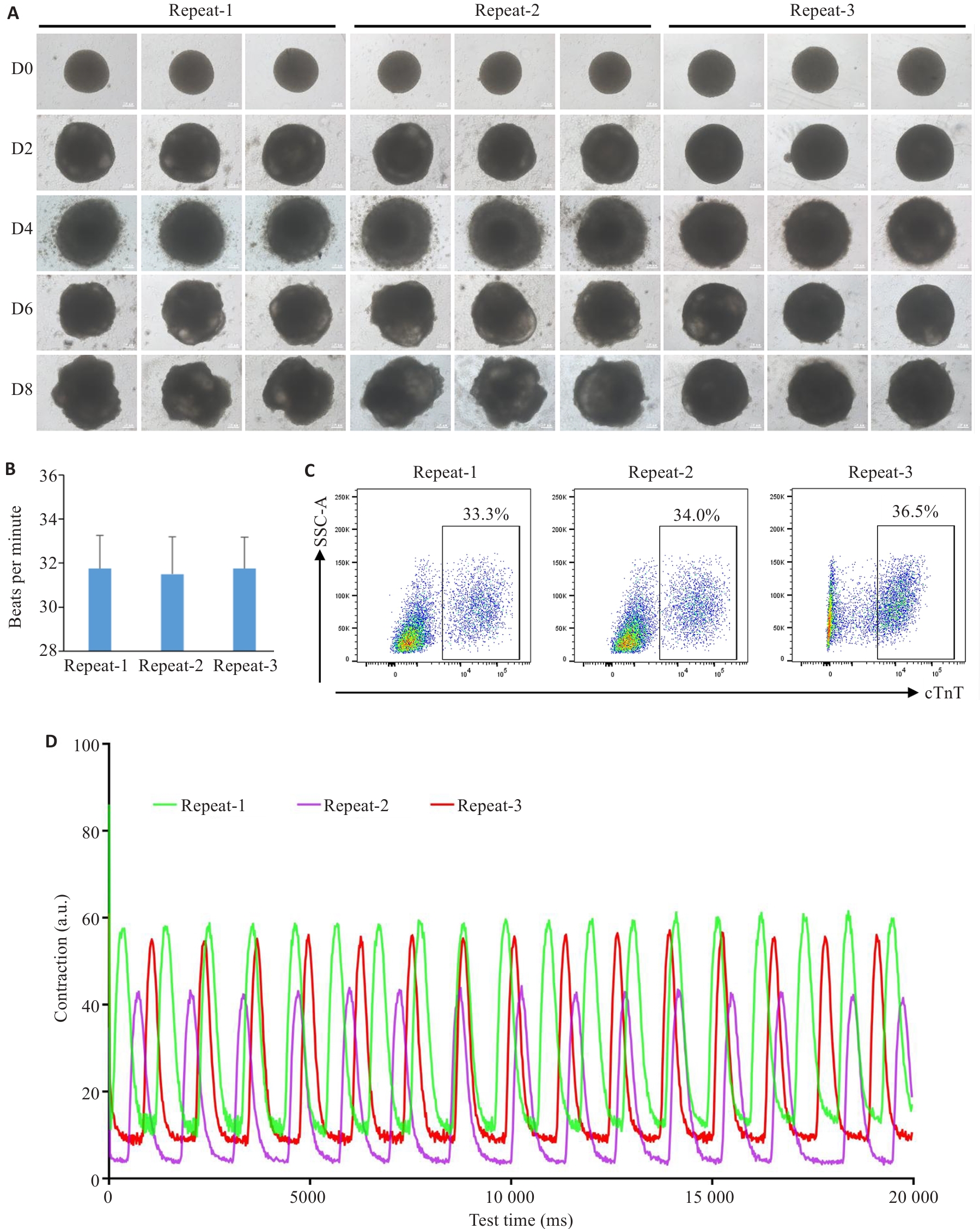

图3 不同批次的心脏类器官一致性检测

Fig.3 Consistency tests of the cardiac organoids from different batches. A: Brightfield images of the developing cardiac organoids from different batches. B: Beating frequency of the cardiac organoids from different batches (n=8). C: Proportion of cardiomyocytes in the cardiac organoids from different batches determined by flow cytometry. D: Measurement of the contractile ability of cardiac organoids using Image J.

图4 心脏类器官长期培养

Fig.4 Long-term culture of the cardiac organoids. A: Brightfield images of the developing cardiac organoids. B: Measurement of contractile ability of the cardiac organoids using Image J. C: Immunofluorescent staining of frozen sections of the cardiac organoids.

图5 心脏类器官建模

Fig.5 Disease modeling of cardiac organoids. A: Brightfield images of the cardiac organoids with different treatments. B: Masson's staining of the cardiac organoids. C: Calcium transient assay of the cardiac organoids. D: Amplitude of Ca2+ transient and the time to peak of Ca2+ transient (n=5). E: mRNA expressions of MYH7 and TNNT2 with or without cryoinjury and captopril treatment. F: Evaluation of cTnT levels in the culture medium by ELISA (n=6). G: Masson's staining of the cardiac organoids. H: TUNEL staining of the organoid sections after H/R treatment. I: Statistical analysis of apoptosis. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group; #P<0.05 vs cryoinjury group.

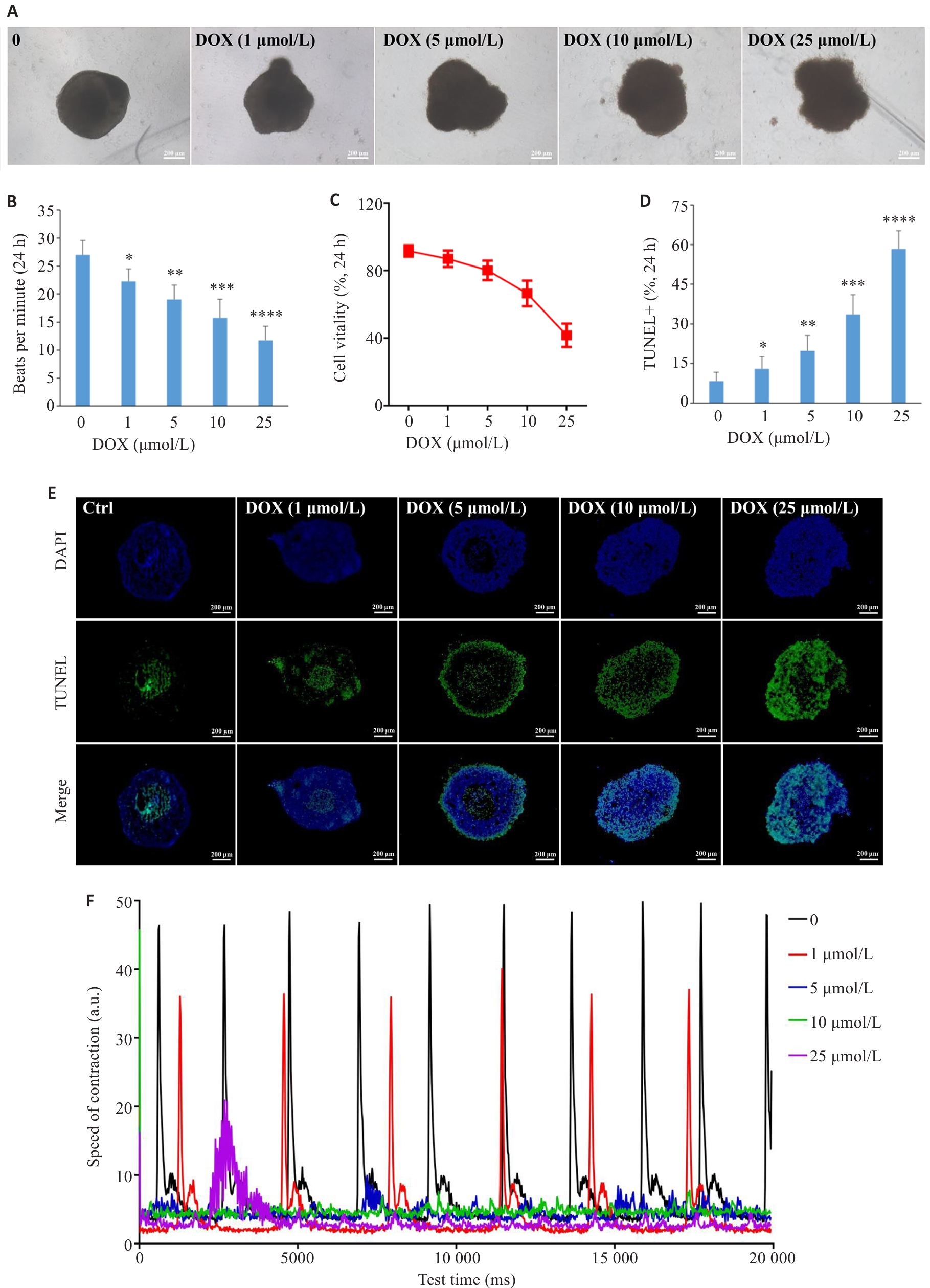

图6 多柔比星对心脏类器官的影响

Fig.6 Effect of doxorubicin on the cardiac organoids. A: Brightfield images of the cardiac organoids treated with doxorubicin (scale bar=200 μm). B: Dose-dependent effects of doxorubicin on beating frequency of the cardiac organoids (n=8). C: Dose-dependent effects of doxorubicin on cell vitality in the cardiac organoids by CCK8 assay. D: Statistical analysis of cell apoptosis. E: TUNEL staining of the organoid sections after exposure to doxorubicin for 24 h at the indicated concentrations. F: Measurement of contractile ability of the cardiac organoids using Image J. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs control group (0).

图7 曲妥珠单抗引起心脏类器官功能异常

Fig.7 Trastuzumab causes dysfunction of the cardiac organoids. A: Calcium transient assay of the cardiac organoids with Trastuzumab treatment. B: Amplitude of Ca2+ transient and the time to peak of Ca2+ transient (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control group, n=5). C: Measurement of contractile ability of the cardiac organoids with Trastuzumab treatment using Image J.

| [1] | Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10226): 795-808. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32008-2 |

| [2] | Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American heart association[J]. Circulation, 2017, 135(10): e146-603. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000491 |

| [3] | Tang XY, Wu SS, Wang D, et al. Human organoids in basic research and clinical applications[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2022, 7(1): 168. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01024-9 |

| [4] | Kapałczyńska M, Kolenda T, Przybyła W, et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures-a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures[J]. Arch Med Sci, 2018, 14(4): 910-9. |

| [5] | Wnorowski A, Yang HX, Wu JC. Progress, obstacles, and limitations in the use of stem cells in organ-on-a-chip models[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2019, 140: 3-11. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.06.001 |

| [6] | Soldatow VY, Lecluyse EL, Griffith LG, et al. In vitro models for liver toxicity testing[J]. Toxicol Res (Camb), 2013, 2(1): 23-39. doi:10.1039/c2tx20051a |

| [7] | Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts[J]. Science, 1998, 282(5391): 1145-7. doi:10.1126/science.282.5391.1145 |

| [8] | Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors[J]. Cell, 2006, 126(4): 663-76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024 |

| [9] | Thomas D, Cunningham NJ, Shenoy S, et al. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells in cardiovascular research: current approaches in cardiac differentiation, maturation strategies, and scalable production[J]. Cardiovasc Res, 2022, 118(1): 20-36. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvab115 |

| [10] | Yang DH, Gomez-Garcia J, Funakoshi S, et al. Modeling human multi-lineage heart field development with pluripotent stem cells[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2022, 29(9): 1382-401. e8. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2022.08.007 |

| [11] | Kim H, Kamm RD, Vunjak-Novakovic G, et al. Progress in multicellular human cardiac organoids for clinical applications[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2022, 29(4): 503-14. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2022.03.012 |

| [12] | Lee SG, Kim YJ, Son MY, et al. Generation of human iPSCs derived heart organoids structurally and functionally similar to heart[J]. Biomaterials, 2022, 290: 121860. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121860 |

| [13] | Arzt M, Pohlman S, Mozneb M, et al. Chemically defined production of tri-lineage human iPSC-derived cardiac spheroids[J]. Curr Protoc, 2023, 3(5): e767. doi:10.1002/cpz1.767 |

| [14] | Lewis-Israeli YR, Wasserman AH, Gabalski MA, et al. Self-assembling human heart organoids for the modeling of cardiac development and congenital heart disease[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 5142. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25329-5 |

| [15] | Zhang FZ, Qiu H, Dong XH, et al. Single-cell atlas of multilineage cardiac organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. Life Med, 2022, 1(2): 179-95. doi:10.1093/lifemedi/lnac002 |

| [16] | Ho BX, Pang JKS, Chen Y, et al. Robust generation of human-chambered cardiac organoids from pluripotent stem cells for improved modelling of cardiovascular diseases[J]. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2022, 13(1): 529. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-03215-1 |

| [17] | Santoro R, Piacentini L, Vavassori C, et al. An in vitro model for cardiac organoid production: The combined role of geometrical confinement and substrate stiffness[J]. Mater Today Bio, 2025, 31: 101566. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101566 |

| [18] | Song HB, Weinstein HNW, Allegakoen P, et al. Single-cell analysis of human primary prostate cancer reveals the heterogeneity of tumor-associated epithelial cell states[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 141. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27322-4 |

| [19] | Rossi G, Manfrin A, Lutolf MP. Progress and potential in organoid research[J]. Nat Rev Genet, 2018, 19(11): 671-87. doi:10.1038/s41576-018-0051-9 |

| [20] | Rossi G, Broguiere N, Miyamoto M, et al. Capturing cardiogenesis in gastruloids[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2021, 28(2): 230-40. e6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2020.10.013 |

| [21] | Drakhlis L, Biswanath S, Farr CM, et al. Human heart-forming organoids recapitulate early heart and foregut development[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2021, 39(6): 737-46. doi:10.1038/s41587-021-00815-9 |

| [22] | Song M, Choi DB, Im JS, et al. Modeling acute myocardial infarction and cardiac fibrosis using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived multi-cellular heart organoids[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2024, 15(5): 308. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-06703-9 |

| [23] | Arhontoulis DC, Kerr CM, Richards D, et al. Human cardiac organoids to model COVID-19 cytokine storm induced cardiac injuries[J]. J Tissue Eng Regen Med, 2022, 16(9): 799-811. doi:10.1002/term.3327 |

| [24] | Richards DJ, Li Y, Kerr CM, et al. Human cardiac organoids for the modelling of myocardial infarction and drug cardiotoxicity[J]. Nat Biomed Eng, 2020, 4(4): 446-62. doi:10.1038/s41551-020-0539-4 |

| [25] | Gopal S, Rodrigues AL, Dordick JS. Exploiting CRISPR Cas9 in three-dimensional stem cell cultures to model disease[J]. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2020, 8: 692. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00692 |

| [26] | Hofbauer P, Jahnel SM, Papai N, et al. Cardioids reveal self-organizing principles of human cardiogenesis[J]. Cell, 2021, 184(12): 3299-317.e22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.034 |

| [27] | Schmidt C, Deyett A, Ilmer T, et al. Multi-chamber cardioids unravel human heart development and cardiac defects[J]. Cell, 2023, 186(25): 5587-605.e27. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.030 |

| [28] | Hoang P, Kowalczewski A, Sun SY, et al. Engineering spatial-organized cardiac organoids for developmental toxicity testing[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2021, 16(5): 1228-44. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.013 |

| [29] | Yang JS, Lei W, Xiao Y, et al. Generation of human vascularized and chambered cardiac organoids for cardiac disease modelling and drug evaluation[J]. Cell Prolif, 2024, 57(8): e13631. doi:10.1111/cpr.13631 |

| [30] | Paik DT, Chandy M, Wu JC. Patient and disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells for discovery of personalized cardiovascular drugs and therapeutics[J]. Pharmacol Rev, 2020, 72(1): 320-42. doi:10.1124/pr.116.013003 |

| [31] | Marini V, Marino F, Aliberti F, et al. Long-term culture of patient-derived cardiac organoids recapitulated Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy and disease progression[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 10: 878311. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.878311 |

| [32] | Filippo Buono M, von Boehmer L, Strang J, et al. Human cardiac organoids for modeling genetic cardiomyopathy[J]. Cells, 2020, 9(7): 1733. doi:10.3390/cells9071733 |

| [33] | Garreta E, Kamm RD, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, et al. Rethinking organoid technology through bioengineering[J]. Nat Mater, 2021, 20(2): 145-55. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-00804-4 |

| [34] | Zhang S, Wan ZP, Kamm RD. Vascularized organoids on a chip: strategies for engineering organoids with functional vasculature[J]. Lab Chip, 2021, 21(3): 473-88. doi:10.1039/d0lc01186j |

| [35] | Kim H, Wang MQ, Paik DT. Endothelial-myocardial angiocrine signaling in heart development[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021, 9: 697130. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.697130 |

| [1] | 李洋洋, 徐佳佳, 姜诚诚, 陈子龙, 陈 颖, 应梦娇, 王 澳, 马彩云, 王春景, 郭 俣, 刘长青. Rho激酶抑制剂Y27632促进人诱导多能干细胞来源原始神经上皮细胞向多巴胺能神经前体细胞的转化[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2024, 44(2): 236-243. |

| [2] | 徐佳佳, 李洋洋, 仲光尚, 方祝玲, 刘淳博, 马彩云, 王春景, 郭 俣, 刘长青. 人诱导多能干细胞体外定向分化为多巴胺能神经元祖细胞[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2023, 43(2): 175-182. |

| [3] | 方丽君, 冯子倍, 梅静怡, 周嘉辉, 林展翼. 低氧环境可体外促进人诱导多能干细胞分化为拟胚体[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2022, 42(6): 929-936. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||