2. 深圳市龙岗区骨科医院麻醉科,广东 深圳 518116

2. Department of Anesthesiology, Longgang Orthopedics Hospital, Shenzhen 518116, China

目前许多研究证明,丙泊酚不但导致发育期大脑神经元广泛的凋亡[1-5],也可导致少突胶质细胞的凋亡增多[1-5]。少突胶质细胞合成的髓鞘碱性蛋白(MBP),是中枢神经系统中髓鞘的重要组成部分,由其形成的有髓神经纤维连接大脑不同区域,参与人和动物的行为及认知过程[7-8]。出生后10 d之内的啮齿类动物暴露于丙泊酚时,镇静剂量[9]和更高的麻醉剂量[10]均可导致神经元明显凋亡,但少突胶质细胞的影响与丙泊酚暴露剂量是否相关尚未见报道。前期研究,我们建立了胚胎期斑马鱼丙泊酚暴露模型[11],并利用该模型发现丙泊酚胚胎期暴露导致MBP蛋白表达下调以及少突胶质细胞凋亡增多[6];也发现丙泊酚可抑制不同发育期SD乳鼠MBP mRNA与蛋白的表达,其中以7 d(P7)、14 d(P14)最为显著[12]。本研究以P7 SD乳鼠为研究对象,进一步观察不同剂量丙泊酚对少突胶质细胞MBP蛋白的影响以及脑内胼胝体和内囊处的髓鞘形成情况。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验动物孕19~21 d SD大鼠6只,由南方医科大学实验动物中心提供。待其自然分娩,每只孕鼠产仔8~14只,共63只。出生当日记为P0,本研究选用出生后第7天(P7)SD乳鼠作为研究对象。

1.2 主要药品及试剂丙泊酚注射液(得普利麻,10 mg/mL,AstraZeneca UK Limited,批号X15047B),中长链脂肪乳(华瑞制药有限公司,80GG051),逆转录试剂盒(TaKaRa,RR036),qRT-PCR试剂盒(TaKaRa,RR820),qRT-PCR引物(上海生工股份有限公司),兔抗大鼠MBP多克隆抗体(Abcam,ab40390),小鼠抗大鼠Active Caspase-3单克隆抗体(Bioss,bsm-33199M),兔抗大鼠Cleaved Caspase-3多克隆抗体(Bioss,bs-0081R),兔抗大鼠β-actin多克隆抗体(Bioss,bs-0061R),Alexa Flour 488标记山羊抗兔IgG(碧云天,A0423),CY3标记山羊抗小鼠IgG(碧云天,A0521),HRP标记山羊抗兔IgG(弗德生物,FD0128),BCA试剂盒(碧云天,P0010S),qRT-PCR仪(Roche,LC480),全自动荧光显微镜(Olympus,BX63)。

1.3 实验方法 1.3.1 实验分组及动物模型建立将其中57只P7 SD乳鼠随机分为5组(其余6只备用):对照组(n=13)、溶剂组(n=5)、25、50、100 mg/kg丙泊酚组(各组n=13)。

丙泊酚组按分组剂量分别计算给药量后腹腔注射,0.4 mL/只,体积不足者用生理盐水补齐。溶剂组和对照组分别腹腔注射等体积的中长链脂肪乳剂和生理盐水。将处于麻醉状态的乳鼠放入37 ℃充氧恒温箱中,密切观察乳鼠肤色和呼吸频率,待麻醉苏醒后放回母鼠身边正常哺乳。给药后8 h和24 h,用1%的戊巴比妥8 μL/g腹腔注射深麻醉后取材。

1.3.2 qRT-PCR检测mbp、caspase-3 mRNA的转录水平用Trizol法提取总RNA,测量其浓度和纯度,然后取适量RNA进行逆转录得到cDNA。按照TaKaRa, RR820试剂盒说明书加样扩增反应体系,反应条件为:预变性,95 ℃ 30 s;扩增,95 ℃ 5 s,60 ℃ 30 s,40个循环;冷却至50 ℃。引物序列:mbp上游引物5'-GCTTC CTCCCAAGGCACA-3',下游引物5'-GGTAGCAATA CGGGTTGACATAG-3';caspase-3上游引物5'-TCCA CGAGCAGAGTCAAAGG-3',下游引物5'-AACAAG CCAACCAAGTTCACA-3';β-actin上游引物5'-TGA CAGGATGCAGAAGGAGA-3',下游引物5'-TAGAG CCACCAATCCACACA-3'。以β-actin作为内参,所得Ct值计算出2-△△Ct来评价mRNA相对表达量。

1.3.3 Western blot检测MBP、Cleaved Caspase-3蛋白表达水平用RIPA裂解组织,提取大脑总蛋白,BCA法定量蛋白浓度,每孔上样量为50 μg。配制15% SDSPAGE凝胶,恒压电泳后转移至PVDF膜。5%脱脂奶粉室温封闭2 h,TBST洗膜1次后分别加入一抗MBP(1: 1500),Cleaved Caspase-3(1:1000),β- actin(1:2000)4 ℃孵育过夜。次日洗膜后加入二抗(HRP标记山羊抗兔IgG,1:15 000)室温孵育1 h。浸泡于ECL发光液,用凝胶成像系统采集图像,所采集图像用Image J软件分析目标条带的灰度值。

1.3.4 免疫荧光检测少突胶质细胞凋亡戊巴比妥麻醉后开胸,分别用预冷的0.9%生理盐水和4%多聚甲醛心脏灌注取脑。4%多聚甲醛固定24 h,然后进行组织脱水、包埋、连续冠状面切片,厚度为4 μm。免疫荧光染色:60 ℃烤片1~2 h;常规脱蜡复水;在柠檬酸盐缓冲液中用微波加热法进行抗原修复,冷却至室温;通透后加5%牛血清蛋白室温封闭1 h;滴加一抗MBP(1:300)、Active Caspase-3(1:300)4 ℃共孵育过夜;次日洗去一抗,加入二抗Alexa Flour 488标记山羊抗兔IgG(1: 500)、CY3标记山羊抗小鼠IgG(1:500),室温避光共孵育1 h;DAPI染色细胞核后用抗荧光淬灭剂封片,荧光显微镜下观察拍照。

1.3.5 免疫荧光染色检测MBP在大脑胼胝体和内囊处的表达MBP染色是一种检测大脑髓鞘形成的敏感方法。给药后24 h灌注取脑,制片和染色等方法如前所述,一抗使用MBP(1:300),二抗使用Alexa Flour 488标记山羊抗兔IgG(1:500)。在相同曝光参数下,用扫描荧光显微镜扫描整个脑片区域,重点观察胼胝体和内囊处MBP表达情况。

1.3.6 统计学处理计量资料以均数±标准差表示,采用SPSS20.0软件进行单因素方差分析,两两之间多重比较采用LSD法。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 丙泊酚单次腹腔注射对乳鼠生理反射的影响乳鼠分别腹腔注射25、50和100 mg/kg丙泊酚后,均在5 min内翻正反射消失,其中50和100 mg/kg丙泊酚组疼痛反射消失(齿镊夹尾未出现体动反应),平均起效时间为397±10 s和286±20 s。3种剂量丙泊酚暴露后恢复时间(从给药到恢复翻正反射的时间)分别为69±7、133±9、260±17 min(表 1)。所有接受丙泊酚腹腔注射的乳鼠未发现皮肤颜色和呼吸方式的明显改变,溶剂组脂肪乳注射后与对照组相比乳鼠精神状态未发生明显变化。

| 表 1 不同剂量丙泊酚对乳鼠生理反射的影响 Tab.1 Effect of different doses of propofol on physiological reflexes in neonatal rats (Mean±SD, n=13) |

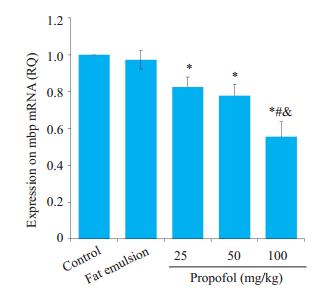

与对照组相比,各丙泊酚组mbp mRNA转录水平明显降低(P < 0.05,图 1),其中100 mg/kg丙泊酚组较25和50 mg/kg丙泊酚组降低程度更大,且差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 1)。与转录结果一致,各丙泊酚组MBP合成呈现出明显的剂量相关性减少(P < 0.05,图 2A,B)。溶剂组mbp mRNA转录和MBP合成均无明显改变(P > 0.05,图 2A,B)。

|

图 1 丙泊酚暴露后8 h对mbp mRNA转录的影响 Fig.1 Effect of propofol on mbp mRNA expression level at 8 h after the injection (Mean±SD, n=5). *P < 0.05 vs control group; #P < 0.05 vs 25 mg/kg propofol group; &P < 0.05 vs 50 mg/kg propofol group |

|

图 2 丙泊酚暴露后8 h对MBP合成的影响 Fig.2 Effect of propofol on MBP expression at 8 h after injection (Mean ± SD, n=5). A: Western blots of MBP expression; B: Quantitative analysis of MBP expression; *P < 0.05, control group; #P < 0.05 vs 25 mg/kg propofol group; &P < 0.05 vs 50 mg/kg propofol group |

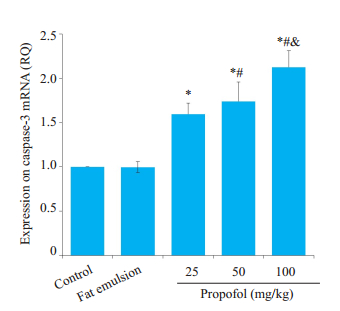

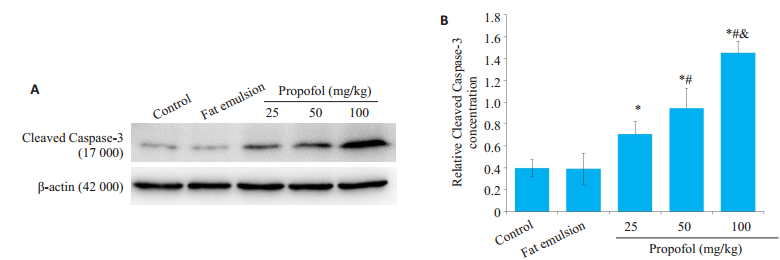

各丙泊酚组较空白对照组caspase-3 mRNA表达明显上调,且具有剂量相关性(P < 0.05,图 3),100 mg/kg丙泊酚组高达对照组的2倍。同样,与对照组相比各丙泊酚组Cleaved Caspase-3表达呈梯度上调趋势,且各剂量组间差异具有显著性(P < 0.05,图 4)。溶剂组无明显改变(P > 0.05,图 3、4)。

|

图 3 丙泊酚暴露后8 h对caspase-3 mRNA表达的影响 Fig.3 Effect of propofol on caspase- 3 mRNA expression level at 8 h after injection (Mean ± SD, n=5). *P < 0.05 vs control group; #P < 0.05 vs 25 mg/kg propofol group; &P < 0.05 vs 50 propofol mg/kg group |

|

图 4 丙泊酚暴露后8 h对Cleaved Caspase-3表达的影响 Fig.4 Effect of propofol on Cleaved Caspase-3 expression at 8 h after injection (Mean±SD, n=5). A: Western blots of Cleaved Caspase- 3; B: Quantitative analysis of Cleaved Caspase- 3 expression; *P < 0.05 vs control group; #P < 0.05 vs 25 mg/kg propofol group; &P < 0.05 vs 50 mg/kg propofol group |

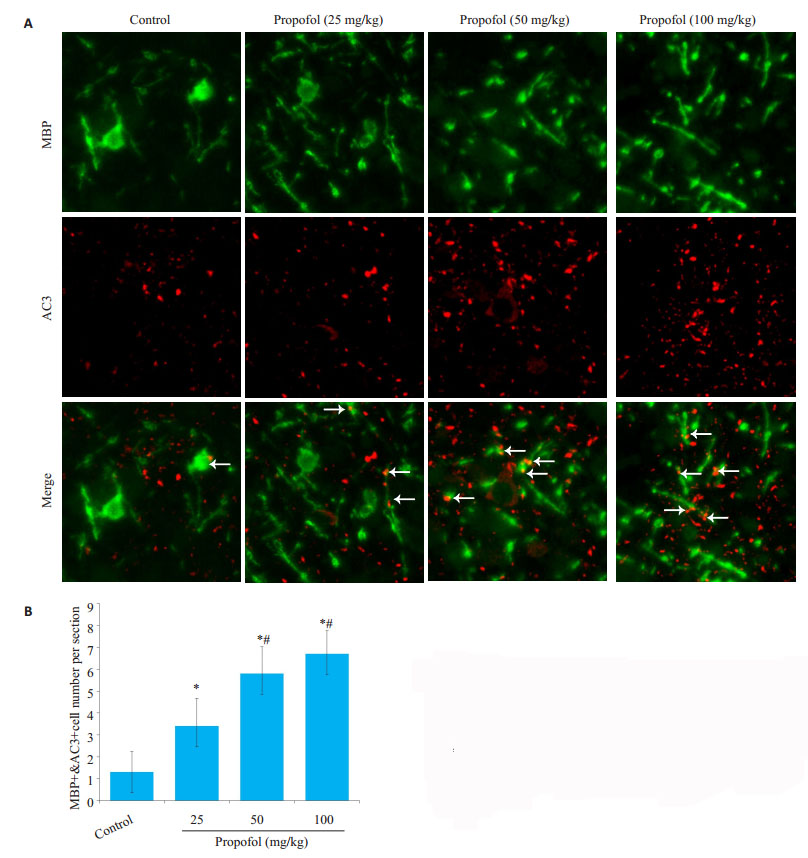

与对照组相比,各丙泊酚组少突胶质细胞凋亡数量明显增多(P < 0.05,图 5)。50和100 mg/kg丙泊酚组较25 mg/kg丙泊酚组有显著增多(P < 0.05,图 5)。

|

图 5 丙泊酚暴露后8 h对少突胶质细胞凋亡的影响 Fig.5 Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes at 8 h after propofol injection (Mean ± SD, n=4). A: Apoptotic oligodendrocytes were double stained (arrow, orange) for MBP (green) and Cleaved Caspase-3 (red) (scale bar=20 μm); B: Quantitative analysis of apoptotic oligodendrocytes. *P < 0.05 vs control group; #P < 0.05 vs 25 mg/kg propofol group |

丙泊酚暴露后24 h,进行MBP荧光染色观察胼胝体和内囊处髓鞘形成情况。胼胝体处MBP染色为丝状,内囊处MBP染色为片状。在胼胝体处,与对照组相比,100 mg/kg丙泊酚组MBP染色的平均光密度值(AOD)明显降低(P < 0.05,图 6A,C)。在内囊处,与对照组相比,50和100 mg/kg丙泊酚组MBP染色的平均光密度值均有显著性降低,且MBP阳性面积也明显减少(P < 0.05,图 6B,C)。25 mg/kg丙泊酚组与对照组相比,胼胝体和内囊部位MBP染色均未见明显变化(P > 0.05,图 6C)。

|

图 6 丙泊酚暴露后24 h胼胝体和内囊处髓鞘形成情况 Fig.6 Myelination in the corpus callosum (A) and the internal capsule (B) at 24 h after propofol injection (Mean ± SD, n=4; scale bar=200 μm). C: Average optical density (AOD) of the corpus callosum and the internal capsule; *P < 0.05 vs control group |

全麻药物在小儿大脑发育期应用的安全性一直以来都备受关注,最新由GAS发布的权威报道中称在婴儿期单次、短时间接受全身麻醉,对神经发育无害[13]。然而作者也指出本次临床观察中仅使用了吸入麻醉药七氟醚,具有一定的局限性。静脉全身麻醉药物丙泊酚,同样普遍应用于小儿外科手术麻醉的诱导和维持,但在婴幼儿期应用的安全性还未有准确的临床结果。

针对丙泊酚对发育期大脑可能产生负面影响,从不同动物暴露模型[5, 14]、不同暴露时期[15-16]、不同暴露剂量[9-10]等多方面研究证明了丙泊酚可以导致发育期大脑神经元凋亡明显增加和树突形成减少。也有一些结果表明丙泊酚暴露后少突胶质细胞凋亡增多以及相关蛋白MBP表达受抑制[5, 11],亚麻醉剂量是否能影响少突胶质细胞,影响是否具有剂量相关性,对少突胶质细胞的损伤是否会影响到髓鞘形成等问题都未见报道。本次研究采用P7 SD乳鼠,对上述问题进行进一步探究。

据估计,大鼠出生后1周的神经发育相当于人类出生时期,正是大脑发育的高峰时期。人类孕28周时胎儿开始髓鞘发育[17-18],相反大鼠的髓鞘化发生在出生以后[19],P0~P15髓鞘快速形成,1周龄是少突胶质细胞分化成熟和髓鞘形成的高峰期[20-21]。有研究表明丙泊酚对少突胶质细胞的易损期是晚期少突祖细胞分化成熟并开始形成髓鞘的这一阶段[5]。因此我们选择P7 SD乳鼠作为研究对象。动物实验中诱导使其失去翻正反射和疼痛反射的所需剂量称为麻醉剂量,仅失去翻正反射,疼痛反射仍然存在的剂量成为亚麻醉剂量,也叫镇静剂量[22]。据此,本实验腹腔注射25 mg/kg丙泊酚为乳鼠的亚麻醉剂量,50和100 mg/kg为其麻醉剂量。在新生大脑发育期低温、低氧、疼痛等不良因素都可以引起神经元或少突胶质细胞的损伤[23-25]。本研究中未发现乳鼠呼吸频率和皮肤颜色发生明显改变,排除了相关混杂因素,以明确后续检测到少突胶质细胞的异常归因于丙泊酚。

人类大脑中胶质细胞占比超过90%,绝大多数大胶质细胞亚型为少突胶质细胞。最初少突胶质细胞前体细胞由端脑腹侧神经干细胞发育而来,随后分化成熟为少突胶质细胞。在中枢神经系统中,成熟少突胶质细胞与神经元轴突发生复杂的相互作用,形成髓鞘,从而为轴突提供绝缘性以及增强动作电位在郎飞结处的跳跃式传导[26]。成熟少突胶质细胞分泌的MBP和肌动蛋白之间相互作用参与髓鞘的包裹和压实。MBP在调节髓鞘膜结构的形态和稳定性中起着至关重要作用[27]。前期研究表明,麻醉剂量的丙泊酚可以导致斑马鱼和SD乳鼠mbp mRNA和MBP蛋白表达同时下调[11-12]。本次实验我们发现仅25 mg/kg单次腹腔注射的亚麻醉剂量丙泊酚就可以明显抑制mbp mRNA和MBP蛋白的表达,随着剂量的增大表现出梯度减少的趋势,说明丙泊酚对少突胶质细胞MBP的影响具剂量依赖性。比较发现,MBP蛋白表达的减少程度明显大于mRNA。MBP是一种长寿蛋白,一旦产生并形成髓鞘将伴随一生,这种蛋白一般存在高度的翻译后修饰[28]。我们检测的是18 000的成熟MBP,因此我们推断丙泊酚对少突胶质细胞MBP翻译后修饰过程的影响程度大于mbp mRNA转录过程,且也有很大可能性是影响mbp mRNA翻译,尤其当丙泊酚剂量达到高麻醉剂量后影响更为明显。

研究表明,丙泊酚可诱导P5~7 C57乳鼠失去疼痛反射的ED50剂量为200 mg/kg,然而该剂量的1/4便可导致明显的神经元凋亡增多[9]。亚麻醉剂量的丙泊酚是否也可以导致少突胶质细胞凋亡的增多呢?Caspase-3与细胞凋亡密切相关,在程序性细胞死亡的内源性和外源性途径中起着重要作用[29]。首先我们检测全脑caspase-3 mRNA和Cleaved Caspase-3蛋白发现其表达明显增高,表明丙泊酚暴露使脑内凋亡细胞数增多;随后用荧光双染证明了部分凋亡细胞为少突胶质细胞,且剂量依赖性增多。综上我们研究表明,在亚麻醉剂量丙泊酚导致神经元广泛凋亡的同时也伴随着少突胶质细胞凋亡的明显增多。

脑白质中胼胝体处的神经纤维束联系左右大脑半球,属于连合纤维;内囊处的神经纤维束联系大脑皮层和脑干、脊髓,属于投射纤维[30]。本研究关注胼胝体和内囊区域神经纤维的髓鞘形成情况。神经纤维早期髓鞘形成的标志是MBP进行性增加,MBP表达多少和分布情况影响着髓鞘的包裹和压实[31],对脑切片进行MBP免疫荧光染色观察髓鞘形成情况较传统的坚牢蓝染色法更为敏感[32]。通过上述方法我们观察到内囊处50和100 mg/kg丙泊酚组MBP染色AOD值明显降低,胼胝体处仅100 mg/kg丙泊酚组明显降低。综上,说明麻醉剂量丙泊酚可以损伤神经纤维髓鞘的形成,并且对丙泊酚的敏感性存在区域上的差异。依据在小鼠双侧颈动脉狭窄模型中,脑缺血破坏了脑白质的完整性从而导致认知功能障碍[33],我们也可推断丙泊酚导致的认知功能障碍除了与神经元损伤有关,还可能与少突胶质细胞的损伤有关。

综上所述,本研究单次腹腔注射25~100 mg/kg丙泊酚可以诱导mbp mRNA和蛋白表达明显下调,且随剂量增加下调程度越大。同时,少突胶质细胞凋亡增多也呈剂量依赖性,因此我们推断少突胶质细胞凋亡是导致mbp mRNA和蛋白表达明显下调的原因之一。同时本研究表明麻醉剂量丙泊酚可不同程度抑制胼胝体和内囊处神经纤维髓鞘形成,这也可能是后期认知功能障碍的原因之一。然而仍需要我们进一步探讨,如这些改变是否长期存在,超微结构下髓鞘的板层结构是否发生改变,是否会导致长期行为学异常等。

| [1] |

Chidambaran V, Costandi A, D'mello A. Propofol: a review of its role in pediatric anesthesia and sedation[J]. CNS Drugs, 2015, 29(7): 543-63. DOI:10.1007/s40263-015-0259-6 |

| [2] |

Malhotra A, Yosh E, Xiong M. Propofol's effects on the fetal brain for Non-Obstetric surgery[J]. Brain Sci, 2017, 7(8): 107. |

| [3] |

Xiong M, Zhang L, Li J, et al. Propofol-Induced neurotoxicity in the fetal animal brain and developments in modifying these Effects-An updated review of propofol fetal exposure in laboratory animal studies[J]. Brain Sci, 2016, 6(2): 11. DOI:10.3390/brainsci6020011 |

| [4] |

Bosnjak ZJ, Logan S, Liu Y, et al. Recent insights into molecular mechanisms of Propofol-Induced developmental neurotoxicity[J]. Anesth Analg, 2016, 123(5): 1286-96. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001544 |

| [5] |

Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, et al. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2013, 110(Suppl 1): i29-38. |

| [6] |

刘川, 林春水, 郭培培, 等. 胚胎期斑马鱼丙泊酚暴露可下调髓鞘碱性蛋白的表达[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2018, 38(9): 1115-20. |

| [7] |

Simons M, Nave KA. Oligodendrocytes: myelination and axonal support[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2016, 8(1): a20479. |

| [8] |

Eluvathingal TJ, Chugani HT, Behen ME, et al. Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: a diffusion tensor imaging study[J]. Pediatrics, 2006, 117(6): 2093-100. DOI:10.1542/peds.2005-1727 |

| [9] |

Cattano D, Young C, Straiko MM, et al. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain[J]. Anesth Analg, 2008, 106(6): 1712-4. DOI:10.1213/ane.0b013e318172ba0a |

| [10] |

Fredriksson A, Ponten E, Gordh T, et al. Neonatal exposure to a combination of N-methyl-D-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor anesthetic agents potentiates apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent Behavioral deficits[J]. Anesthesiology, 2007, 107(3): 427-36. DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000278892.62305.9c |

| [11] |

Guo P, Huang Z, Tao T, et al. Zebrafish as a model for studying the developmental neurotoxicity of propofol[J]. J Appl Toxicol, 2015, 35(12): 1511-9. DOI:10.1002/jat.3183 |

| [12] |

朱晓勤, 林春水, 郭培培, 等. 丙泊酚对不同发育时期SD大鼠少突胶质细胞鞘磷脂蛋白的影响[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2017, 37(12): 1615-9. |

| [13] |

Mccann ME, de Graaff JC, Dorris L, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age after general anaesthesia or awakeregional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled equivalence trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(1172): 664-77. |

| [14] |

Li J, Xiong M, Alhashem HM, et al. Effects of prenatal propofol exposure on postnatal development in rats[J]. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 2014, 43(2014): 51-8. |

| [15] |

Xiong M, Li J, Alhashem HM, et al. Propofol exposure in pregnant rats induces neurotoxicity and persistent learning deficit in the offspring[J]. Brain Sci, 2014, 4(2): 356-75. DOI:10.3390/brainsci4020356 |

| [16] |

Pesić V, Milanović D, Tanić N, et al. Potential mechanism of cell death in the developing rat brain induced by propofol anesthesia[J]. Int J Dev Neurosci, 2009, 27(3): 279-87. DOI:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.12.005 |

| [17] |

Clancy B, Finlay BL, Darlington RB, et al. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2007, 28(5): 931-7. DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.01.014 |

| [18] |

Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, et al. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury[J]. J Neurosci, 2001, 21(4): 1302-12. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001 |

| [19] |

Wiggins RC. Myelin development and nutritional insufficiency[J]. Brain Res, 1982, 257(2): 151-75. |

| [20] |

Hartman BK, Agrawal HC, Kalmbach S, et al. A comparative study of the immunohistochemical localization of basic protein to myelin and oligodendrocytes in rat and chicken brain[J]. J Comp Neurol, 1979, 188(2): 273-90. DOI:10.1002/cne.901880206 |

| [21] |

Reemst K, Noctor SC, Lucassen PJ, et al. The indispensable roles of microglia and astrocytes during brain development[J]. Front Hum Neurosci, 2016, 10(8): 566. |

| [22] |

Bosnjak ZJ, Logan S, Liu Y, et al. Recent insights into molecular mechanisms of Propofol-Induced developmental neurotoxicity[J]. Anesth Analg, 2016, 123(5): 1286-96. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001544 |

| [23] |

Back SA, Han BH, Luo NL, et al. Selective vulnerability of late oligodendrocyte progenitors to hypoxia-ischemia[J]. J Neurosci, 2002, 22(2): 455-63. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00455.2002 |

| [24] |

Lee HJ, Kim JW, Yim SV, et al. Fluoxetine enhances cell proliferation and prevents apoptosis in dentate gyrus of maternally separated rats[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2001, 6(6): 725-8. DOI:10.1038/sj.mp.4000947 |

| [25] |

Ruda MA, Ling QD, Hohmann AG, et al. Altered nociceptive neuronal circuits after neonatal peripheral inflammation[J]. Science, 2000, 289(5479): 628-31. DOI:10.1126/science.289.5479.628 |

| [26] |

Rowitch DH. Glial specification in the vertebrate neural tube[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2004, 5(5): 409-19. DOI:10.1038/nrn1389 |

| [27] |

Domingues HS, Cruz A, Chan JR, et al. Mechanical plasticity during oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination[J]. Glia, 2018, 66(1): 5-14. DOI:10.1002/glia.23206 |

| [28] |

Truscott RJ, Friedrich MG. Can the fact that myelin proteins are old and break down explain the origin of multiple sclerosis in Some People[J]. J Clin Med, 2018, 7(9): 281. DOI:10.3390/jcm7090281 |

| [29] |

Khalilzadeh B, Shadjou N, Kanberoglu GS, et al. Advances in nanomaterial based optical biosensing and bioimaging of apoptosis via caspase-3 activity: a review[J]. Mikrochim Acta, 2018, 185(9): 434. DOI:10.1007/s00604-018-2980-6 |

| [30] |

Chenin L, Lefranc M, Velut S, et al. Cortical and subcortical functional neuroanatomy for low-grade glioma surgery[J]. Neurochirurgie, 2017, 63(3): 117-21. DOI:10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.10.001 |

| [31] |

Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, et al. Arrested oligodendrocyte lineage progression during human cerebral white matter development: dissociation between the timing of progenitor differentiation and myelinogenesis[J]. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2002, 61(2): 197-211. DOI:10.1093/jnen/61.2.197 |

| [32] |

Creeley CE, Dikranian KT, Dissen GA, et al. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the fetal rhesus macaque brain[J]. Anesthesiology, 2014, 120(3): 626-38. DOI:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000037 |

| [33] |

Ben-Ari H, Lifschyz T, Wolf G, et al. White matter lesions, cerebral inflammation and cognitive function in a mouse model of cerebral hypoperfusion[J]. Brain Res, 2019, 15(5): 193-201. |

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39