2. 清远市人民医院肿瘤内科,广东 清远 511500

2. Department of Oncology, Qingyuan People's Hospital, Qingyuan 511500, China

宫颈癌是发展中国家女性中发病率第2位及致死率第3位的恶性肿瘤[1]。目前,早期宫颈癌患者治疗后的5年生存率高达90%,而局部晚期或远处转移患者预后仍不理想,特别是Ⅳ期患者的5年生存率仅约20% [2]。尽管以顺铂为基础的同步放化疗可改善局部晚期患者的总生存率和无进展生存期[3],但约50%局部晚期患者在初始治疗后的2年内出现复发[4]。因此,探索宫颈癌发生及进展的机制,寻找预测宫颈癌发生和进展潜在的分子靶点,对改善宫颈癌患者的生存预后有着极其重要的临床价值。SLP-2是stomatin基因超家族的新成员[5]。SLP-2与线粒体内膜紧密相连,位于线粒体内膜与外膜之间的膜间隙内[6]。其功能是调节线粒体蛋白质的稳定性,包括呼吸链复合物的抑制肽和亚基[6]。近年来多项研究发现SLP-2参与肿瘤的发生与发展,与肿瘤细胞的增殖、凋亡、粘附及侵袭等密切相关[7-11]。Huang等[11]发现SLP-2可能通过诱导肝癌细胞EMT的发生促进肝癌的侵袭及转移。有研究发现,上调SLP-2可能会大大增加基质金属蛋白酶9(MMP-9)的表达,其与肿瘤的进展密切相关,如侵袭、迁移、血管生成和体外肿瘤细胞转移等[12-15]。本课题组前期研究发现宫颈癌癌组织中SLP-2的表达明显高于癌旁组织,其高表达与宫颈癌的鳞状细胞癌抗原、深肌层浸润、淋巴脉管浸润、盆腔淋巴结转移情况呈正相关,为盆腔淋巴结转移独立的危险因素[16],提示SLP-2可能参与宫颈癌的发生及进展。然而,SLP-2如何参与宫颈癌的进展目前国内外尚未见报道,因此本研究对此进行了初步探讨。本课题以宫颈癌腺癌Hela细胞及鳞癌Siha细胞为研究对象,用siRNA干扰技术沉默SLP-2基因,行细胞功能实验及分子实验,旨在研究其对宫颈癌细胞迁移和侵袭能力的影响及可能的机制。

1 材料和方法 1.1 细胞株人宫颈腺癌Hela细胞及宫颈鳞癌Siha细胞由南方医院肿瘤内科实验室提供。

1.2 主要试剂DMEM高糖培养基、Opti-MEM培养基、PBS缓冲液、胰蛋白酶-EDTA消化液(Gibco);胎牛血清(Biological Industry);靶向干扰SLP-2的siRNA及阴性对照(锐博生物);Lipofectamine3000脂质体(Invitrogen);全蛋白提取试剂盒及BCA蛋白定量试剂盒(碧云天);兔抗人α-tubulin、β-catenin、SLP-2、Twist多克隆抗体(proteintech);兔抗人E-cadherin多克隆抗体(Genetex),兔抗人vimentin多克隆抗体(cell signaling Technology);抗兔红外发光荧光二抗(LI-COR)。

1.3 细胞培养与RNA干扰人宫颈癌Hela及Siha细胞常规培养于含10%胎牛血清的DMEM高糖培养基,于37 ℃、饱和湿度及含5% CO2的培养箱中传代培养,取对数生长期的细胞用于实验。转染前1 d将2~3×105细胞接种于6孔板中,当细胞融合度达30%~50%时,按Lipofectamine3000脂质体说明书转染细胞。每次实验设4个组:空白对照组(control)、阴性对照组(siNC)、siSLP-2-s1沉默组、siSLP-2-s2沉默组。其中,siSLP-2-s1正义链为5'-CGA CAAUGUAACUCUGCAAtt-3',siSLP-s2正义链为5'- GGGUGAAAGAGUCUAUGCAtt-3',siNC正义链为:5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3'。

1.4 划痕实验收集siRNA转染48 h后的各组细胞,以每孔5×105 Hela细胞、6×105 Siha细胞接种于12孔板,待细胞生长密度达90%以上时,用10 µL枪头比着直尺在12孔板内画横竖两条直线,用PBS漂洗2次,洗去漂浮的细胞,用含1%血清的DMEM高糖培养基继续培养,于100倍倒置显微镜下观察并拍摄划痕愈合情况,其中Hela细胞取0 h及48 h,Siha细胞取0 h及36 h,每次实验每组取5个视野。

1.5 Transwell迁移实验将transwell小室置于24孔板中,下室加入500 µL含10%胎牛血清的DMEM高糖培养基。收集siRNA转染48 h后的各组细胞,用无血清DMEM高糖培养基重悬,以每孔1×105 Hela细胞、5×104 Siha细胞接种于transwell小室的上室。培养24 h后,取出各组小室,用棉签沾取PBS后轻轻擦拭小室膜的上层以去除未穿膜的细胞,用4%多聚甲醛固定及0.1%结晶紫染色,于200倍正置显微镜下随机选取5个视野拍照计数。

1.6 基质胶transwell侵袭实验将transwell小室置于24孔板中,按R & D公司使用说明书,将基质胶均匀涂布于各小室底部,收集siRNA转染48 h后的各组细胞,用无血清DMEM高糖培养基重悬,以每孔2×105 Hela细胞、1×105 Siha细胞接种于transwell小室的上室,下室加入500 µL含10%胎牛血清的DMEM高糖培养基。培养48 h后,取出各组小室,用棉签沾取PBS后轻轻擦拭小室膜的上层以去除未穿膜的细胞,用4%多聚甲醛固定及0.1%结晶紫染色,于200倍正置显微镜下随机选取5个视野拍照计数。

1.7 Western blot检测蛋白表达siRNA转染48 h后,用含有1 mmol PMSF和蛋白酶抑制剂混合物的lysis buffer裂解缓冲液提取各组细胞的总蛋白,BCA法测定蛋白浓度后,按30 µg的蛋白上样量上样于分离胶浓度为10%的SDS-PAGE电泳,200 mA恒流转膜2 h,5%脱脂奶粉室温封闭1 h,一抗4 ℃孵育过夜,TBST洗涤3次×10 min/次,荧光二抗室温避光孵育1 h,避光TBST洗涤3次×10 min/次,条带于干净滤纸中夹干,用Odyssey近红外成像系统扫描成像。

1.8 统计学方法采用SPSS22.0软件进行统计分析。计量资料均以均数±标准差表示。采用两独立样本t检验比较对照组及实验组之间的差异,P(双侧检验) < 0.05认为差异具有统计学意义。图片数据的采集及处理用Image J软件进行。每次实验重复3次以上。

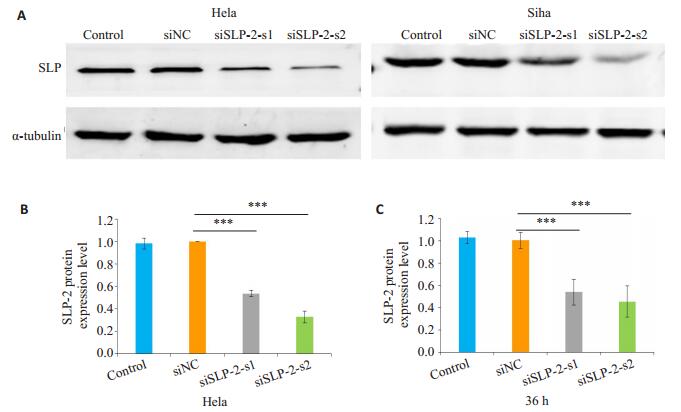

2 结果 2.1 沉默SLP-2能有效下调Hela和Siha细胞中SLP-2蛋白的表达Western blot结果显示,与control组、siNC组相比,沉默组siSLP-2-s1及siSLP-2-s2的SLP-2的表达量均显著下调(P < 0.01,图 1)。

|

图 1 siSLP-2对Hela和Siha细胞SLP-2表达的下调作用 Figure 1 Effect of siSLP-2 on SLP-2 expression in Hela and Siha cells. A: Expression of SLP-2 detected by Western blot; B, C: Quantitative analysis of the results of Western blotting. ***P < 0.01. |

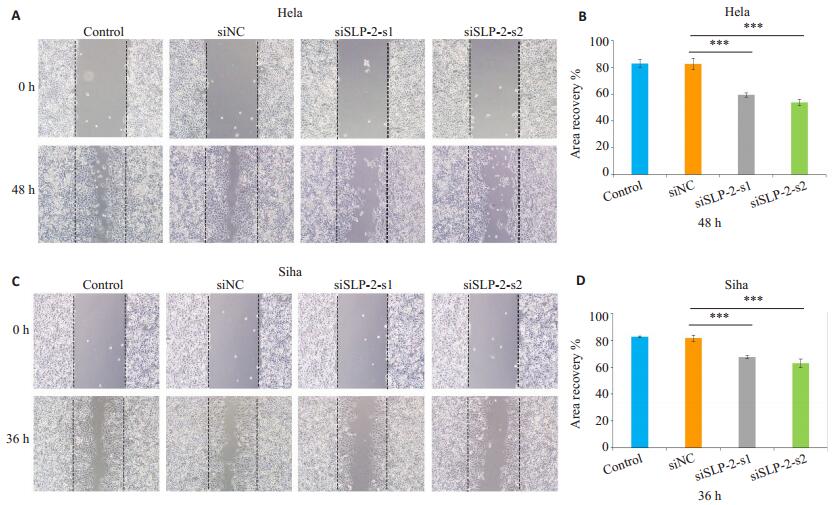

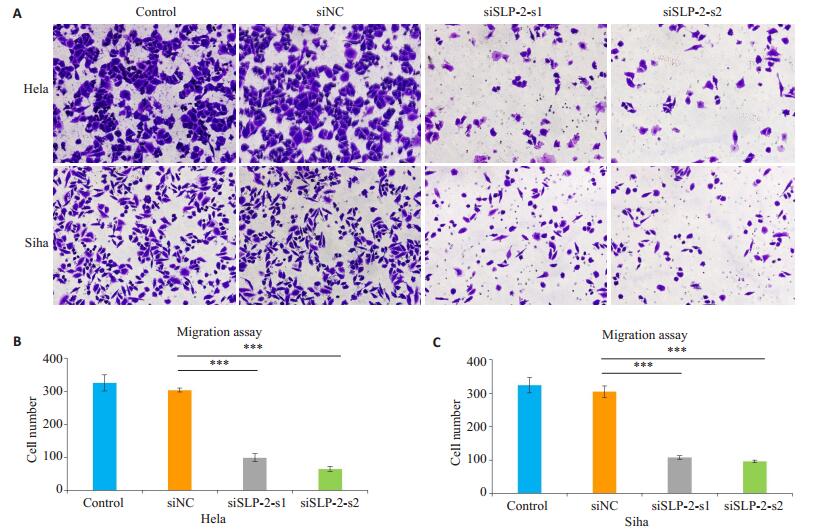

划痕实验结果显示,转染siRNA 48 h后,沉默组siSLP-2-s1及siSLP-2-s2组细胞划痕面积愈合百分比与control组及siNC组相比均明显减少(P < 0.01,图 2)。同样,Transwell迁移实验显示,转染siRNA 48 h后,沉默组siSLP-2-s1及siSLP-2-s2组细胞从上室穿过小室膜至下室的细胞数较control组及siNC组明显减少(P < 0.01,图 3)。

|

图 2 划痕实验观察沉默SLP-2基因对Hela、Siha细胞迁移能力的影响 Figure 2 Migration ability of Hela and Siha cells after si-SLP-2 transfection shown by wound healing assay (Original magnification: ×100). A, C: Wound healing assay; B, D: Quantitative analysis of wound healing area. ***P < 0.01. |

|

图 3 Transwell迁移实验观察沉默SLP-2基因对Hela、Siha细胞迁移能力的影响 Figure 3 Migration ability of Hela and Siha cells after si-SLP-2 transfection shown by Transwell assay (×200). A: Transwell assay; B, C: Quantitative analysis of cell migration. ***P < 0.01. |

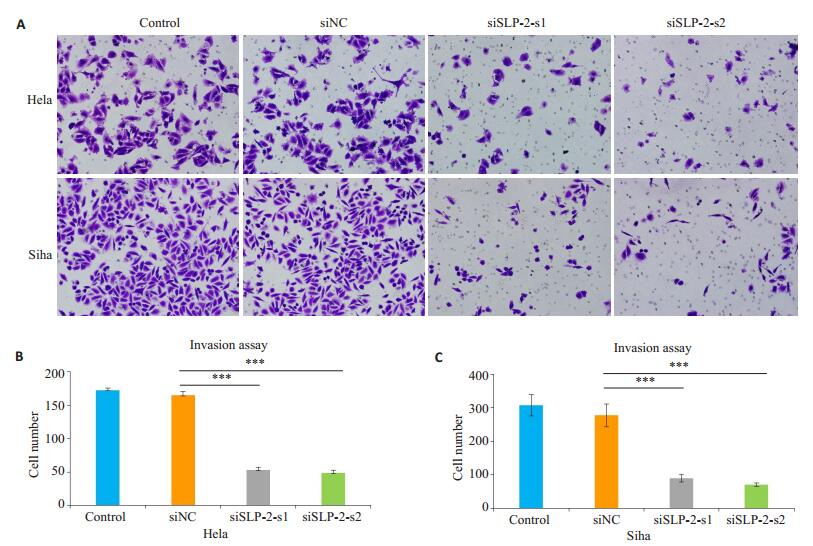

基质胶Transwell侵袭实验显示,转染siRNA 48 h后,沉默组siSLP-2-s1及siSLP-2-s2组细胞从上室穿过小室膜至下室的细胞数,较control组及siNC组明显减少(P < 0.01,图 4)。

|

图 4 Transwell侵袭实验观察沉默SLP-2基因对Hela、Siha细胞侵袭能力的影响 Figure 4 Invasion ability of Hela and Siha cells after si-SLP-2 transfection shown by Matrigel-coated Transwell assay (×200). A: Matrigel-coated Transwell assay; B, C: Quantitative analysis of cell invasion. ***P < 0.01. |

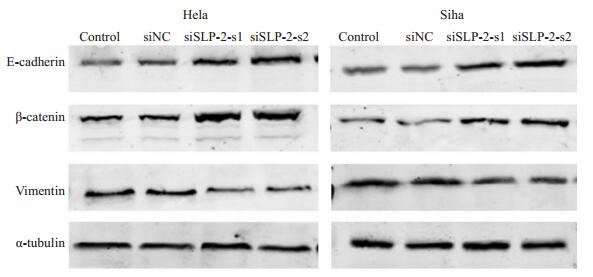

Western blot结果显示,沉默SLP-2后,Hela细胞及Siha细胞的上皮细胞标志分子E-cadherin、β-catenin表达上调,而间质细胞标志分子vimentin表达下调(图 5)。

|

图 5 Western blot实验检测沉默SLP-2基因对Hela、Siha细胞上皮间质转化分子标志蛋白的影响 Figure 5 Expression of EMT-related molecular markers detected by Western blotting in Hela and Siha cells after si-SLP-2 transfection. |

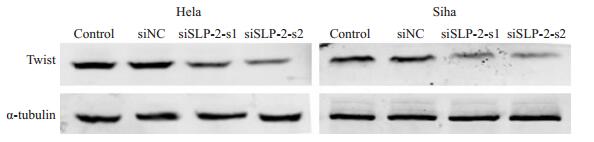

Western blot结果显示,沉默SLP-2后,EMT上游转录因子Twist表达下降(图 6)。

|

图 6 Western blot实验检测沉默SLP-2基因对Hela、Siha细胞EMT上游转录因子Twist蛋白的影响 Figure 6 Effect of silencing SLP-2 on the expression of Twist in Hela and Siha cells detected by Western blotting. |

众所周知,发生转移的肿瘤比未发生转移的肿瘤更难治疗[17-18]。肿瘤发生转移是宫颈癌进展及治疗失败的重要原因,寻找宫颈癌转移及进展的机制是当前研究的热点。我们课题组前期研究发现沉默SLP-2后HeLa、HCC94细胞株的凋亡增多,而过表达SLP-2可促进Siha细胞的增殖及通过线粒体凋亡途径抑制Siha细胞的凋亡,表明SLP-2可能在宫颈癌中发挥促癌作用[16, 19];同时,我们发现SLP-2的高表达与宫颈癌深肌层浸润、淋巴脉管浸润、盆腔淋巴结转移、鳞状细胞癌抗原相关,为盆腔淋巴结转移独立的危险因素[16]。因此我们猜测SLP-2可能参与促进宫颈癌的侵袭及转移。为明确SLP-2对宫颈癌侵袭及转移的影响,本研究用siRNA干扰技术下调宫颈腺癌Hela细胞和鳞癌Siha细胞的SLP-2的表达,通过划痕实验、Transwell迁移实验及Transwell侵袭实验,发现下调SLP-2蛋白的表达后,宫颈癌Hela和Siha细胞的迁移能力及侵袭能力均明显下降,表明SLP-2可能参与促进宫颈癌细胞的迁移及侵袭。

研究表明,肿瘤细胞发生上皮-间质转化对肿瘤转移及进展起着决定性作用[20-24]。在上皮-间质转化过程中,具有极性的上皮细胞转化为运动能力增强的间质细胞,进而更易于在细胞外基质中自由移动,导致转移能力增强[25-28]。上皮间质转化的特征之一是上皮细胞表型的丢失,比如E-cadherin、β-catenin等,及间质细胞表型的获得,比如vimentin等[20, 29],进而使肿瘤细胞更具转移性及侵袭性。Huang等[11]发现SLP-2可能通过促进肝癌细胞上皮间质转化的发生进而促进肝癌的侵袭及转移。而我们的研究也发现,下调宫颈癌Hela和Siha细胞SLP-2蛋白的表达后,上皮细胞表型蛋白E-cadherin、β-catenin表达上调,间质细胞表型蛋白vimentin表达下调,表明沉默SLP-2可能通过抑制宫颈癌细胞上皮间质转化的发生,从而使宫颈癌细胞的迁移及侵袭能力下降。

上皮间质转化的发生是受一系列上游转录因子的调节,如Slug, Snail, Twist, ZEB1 and ZEB2等,它们将上皮细胞状态转化为间质细胞状态[30]。其中,Twist是一种螺旋-环-螺旋转录因子,通过促进上皮-间质转化进而促进肿瘤转移[31]。此外有研究表明,Twist水平的升高与E-cadherin蛋白的异常表达有关[32]。本研究结果显示,下调宫颈癌Hela和Siha细胞SLP-2蛋白表达后,EMT上游转录因子Twist蛋白的表达下调,表明沉默SLP-2可能通过下调Twist蛋白的表达从而抑制宫颈癌细胞上皮间质转化的发生,但更深层次的作用机制有待进一步的研究。

综上所述,本研究发现沉默SLP-2能有效抑制宫颈癌细胞的迁移及侵袭能力,表明SLP-2可能在宫颈癌进展中发挥重要的作用,可能是潜在的转移预测标志分子及治疗的新靶点。但本实验局限之处在于缺少体内试验,以及SLP-2介导上皮间质转化促进宫颈癌细胞迁移及侵袭的具体机制有待进步研究。

| [1] |

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J].

CACancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2): 87-108.

DOI: 10.3322/caac.21262. |

| [2] |

Sherman ME, Wang SS, Carreon J, et al. Mortality trends for cervical squamous and adenocarcinoma in the United States[J].

Cancer, 2005, 103(6): 1258-64.

DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142. |

| [3] |

Green JA, Kirwan JM, Tierney JF, et al. Survival and recurrence after concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer of the uterine cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J].

Lancet, 2001, 358(9284): 781-6.

DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05965-7. |

| [4] |

Eifel PJ. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy as the standard of care for cervical cancer[J].

Nat Clin Pract Oncol, 2006, 3(5): 248-55.

DOI: 10.1038/ncponc0486. |

| [5] |

Wang Y, Morrow JS. Identification and characterization of human SLP-2, a novel homologue of stomatin (band 7.2b) present in erythrocytes and other tissues[J].

J Biol Chem, 2000, 275(11): 8062-71.

DOI: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8062. |

| [6] |

Da Cruz S, Parone PA, Gonzalo P, et al. SLP-2 interacts with prohibitins in the mitochondrial inner membrane and contributes to their stability[J].

Biochim BiophysActa, 2008, 1783(5): 904-11.

|

| [7] |

张立勇, 丁芳, 刘仲敏, 等. SLP-2基因反义核酸对食管鳞癌细胞系TE12生长和增殖的影响[J].

癌症, 2005, 24(2): 155-9.

|

| [8] |

Zhang L, Ding F, Cao W, et al. Stomatin-like protein 2 is overexpressed in cancer and involved in regulating cell growth and cell adhesion in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J].

Clin Cancer Res, 2006, 12(5): 1639-46.

DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1858. |

| [9] |

Wang Y, Cao W, Yu Z, et al. Downregulation of a mitochondria associated protein SLP-2 inhibits tumor cell motility, proliferation and enhances cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic reagents[J].

Cancer Biol Ther, 2009, 8(17): 1651-8.

DOI: 10.4161/cbt.8.17.9283. |

| [10] |

Song L, Liu L, Wu Z, et al. Knockdown of stomatin-like protein 2 (STOML2) reduces the invasive ability of glioma cells through inhibition of the NF-κB/MMP-9 pathway[J].

J Pathol, 2012, 226(3): 534-43.

DOI: 10.1002/path.v226.3. |

| [11] |

Huang Y, Chen Y, Lin X, et al. Clinical significance of SLP-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and its regulation in cancer cell proliferation, migration, and EMT[J].

Onco Targets Ther, 2017, 10: 4665-73.

DOI: 10.2147/OTT. |

| [12] |

Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis[J].

Cancer Meta Rev, 2006, 25(1): 9-34.

DOI: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. |

| [13] |

Louis DN, Pomeroy SL, Cairncross JG. Focus on central nervous system neoplasia[J].

Cancer Cell, 2002, 1(2): 125-8.

DOI: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00040-5. |

| [14] |

Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Gelatinases (MMP-2 and-9) and their natural inhibitors as prognostic indicators in solid cancers[J].

Biochimie, 2005, 87(3/4): 287-97.

|

| [15] |

Chintala SK, Tonn JC, Rao JS. Matrix metalloproteinases and their biological function in human gliomas[J].

Int J Dev Neurosci, 1999, 17(5/6): 495-502.

|

| [16] |

Deng H, Deng Y, Liu F, et al. Stomatin-like protein 2 is overexpressed in cervical cancer and involved in tumor cell apoptosis[J].

Oncol Lett, 2017, 14(6): 6355-64.

|

| [17] |

Gupta GP, Massagué J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework[J].

Cell, 2006, 127(4): 679-95.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. |

| [18] |

Pandya P, Orgaz JL, Sanz-Moreno V. Modes of invasion during tumour dissemination[J].

Mol Oncol, 2017, 11(1): 5-27.

DOI: 10.1002/1878-0261.12019. |

| [19] |

胡国林, 姚广裕, 邓欢, 等. STOML-2过表达抑制人宫颈鳞癌Siha细胞凋亡[J].

南方医科大学学报, 2015, 35(9): 1293-6.

|

| [20] |

Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front[J].

Nature, 2006, 441(792): 444-50.

|

| [21] |

Huber MA, Kraut N, Beug H. Molecular requirements for epithelialmesenchymal transition during tumor progression[J].

Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2005, 17(5): 548-58.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001. |

| [22] |

Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease[J].

J Cell Biol, 2006, 172(7): 973-81.

DOI: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. |

| [23] |

Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression[J].

Nat Rev Cancer, 2002, 2(6): 442-54.

DOI: 10.1038/nrc822. |

| [24] |

Tse JC, Kalluri R. Mechanisms of metastasis: epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contribution of tumor microenvironment[J].

J Cell Biochem, 2007, 101(4): 816-29.

DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4644. |

| [25] |

Smith BN, Bhowmick NA. Role of EMT in metastasis and therapy resistance[J].

J Clin Med, 2016, 5(2): E17.

DOI: 10.3390/jcm5020017. |

| [26] |

Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M, Alahari SK. Regulation of epithelialmesenchymal transition through epigenetic and post-translational modifications[J].

Mol Cancer, 2016, 15: 18.

DOI: 10.1186/s12943-016-0502-x. |

| [27] |

Nakaya Y, Sheng G. EMT in developmental morphogenesis[J].

Cancer Lett, 2013, 341(1): 9-15.

DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.037. |

| [28] |

Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits[J].

Nat Rev Cancer, 2009, 9(4): 265-73.

DOI: 10.1038/nrc2620. |

| [29] |

Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WN, Pignatelli M. E-cadherin-catenin cellcell adhesion complex and human cancer[J].

Br J Surg, 2000, 87(8): 992-1005.

DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01513.x. |

| [30] |

Hou CH, Lin FL, Hou SM, et al. Cyr61 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis of osteosarcoma by Raf-1/ MEK/ERK/Elk-1/TWIST-1 signaling pathway[J].

Mol Cancer, 2014, 13: 236.

DOI: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-236. |

| [31] |

Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype[J].

Nat Rev Cancer, 2007, 7(6): 415-28.

DOI: 10.1038/nrc2131. |

| [32] |

Li Y, Wang W, Wang W, et al. Correlation of TWIST2 up-regulation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumorigenesis and progressionofcervicalcarcinoma[J].

GynecolOncol, 2012, 124(1): 112-8.

|

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38