Journal of Southern Medical University ›› 2024, Vol. 44 ›› Issue (5): 960-966.doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2024.05.18

• Basic Research • Previous Articles Next Articles

Mingming LI( ), Liangchao HE, Tianyu LI, Yan BAO, Xiang XU(

), Liangchao HE, Tianyu LI, Yan BAO, Xiang XU( ), Guang CHEN(

), Guang CHEN( )

)

Received:2024-01-05

Online:2024-05-20

Published:2024-06-04

Contact:

Xiang XU, Guang CHEN

E-mail:limingmingwnmc@163.com;xuxiang575883@163.com;chenguang210401@163.com

Mingming LI, Liangchao HE, Tianyu LI, Yan BAO, Xiang XU, Guang CHEN. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury in the parietal cortex inhibits expressions of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the medulla oblongata of mice[J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2024, 44(5): 960-966.

Add to citation manager EndNote|Ris|BibTeX

URL: https://www.j-smu.com/EN/10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2024.05.18

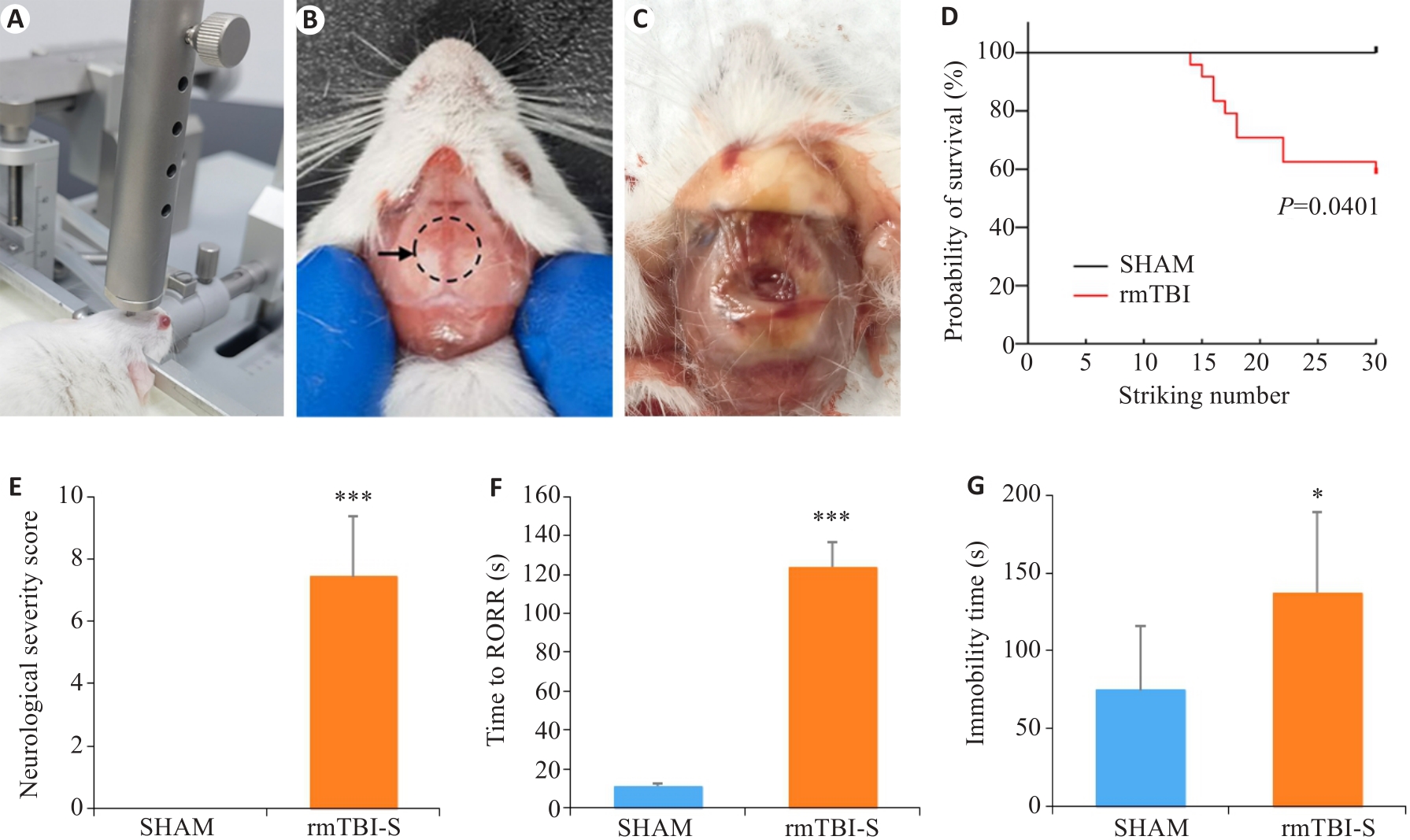

Fig.1 Repeated mild traumatic brain injury (rmTBI) results in death and behavioral changes of mice. A: The free-fall device for inducing rmTBI in mice. B: Impact site on the skull of mice shown by the dashed line circle. C: Wound in the skull after rmTBI. D: The mortality rate of mice increases with the strike number. E: Neurological severity scores of the mice surviving rmTBI. F: The mice surviving rmTBI show delayed recovery of righting reflex (RORR). G: The mice surviving rmTBI show increased immobility time in forced swimming test. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs sham group (nsham=8, nrmTBI-S=10-14).

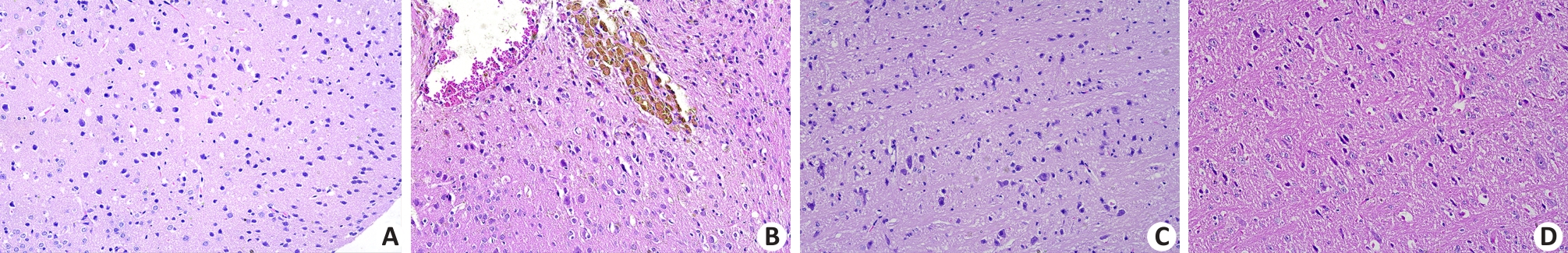

Fig.2 Histopathological changes in the parietal cortex and medulla oblongata of the mice that died after rmTBI (Original magnification: ×20). A: No abnormalities are observed in the parietal cortical neurons in the sham group. B: Tissue defects, bleeding, neuronal edema and deposition of hemosiderin particles are observed in the parietal cortex of a mouse that did not survive rmTBI. C: No abnormalities are observed in the neurons and nerve fibers in the medulla oblongata of a sham-operated mouse. D: Loose, twisted and broken nerve fibers and swollen neurons are observed in the medulla oblongata of a mouse that did not survive rmTBI.

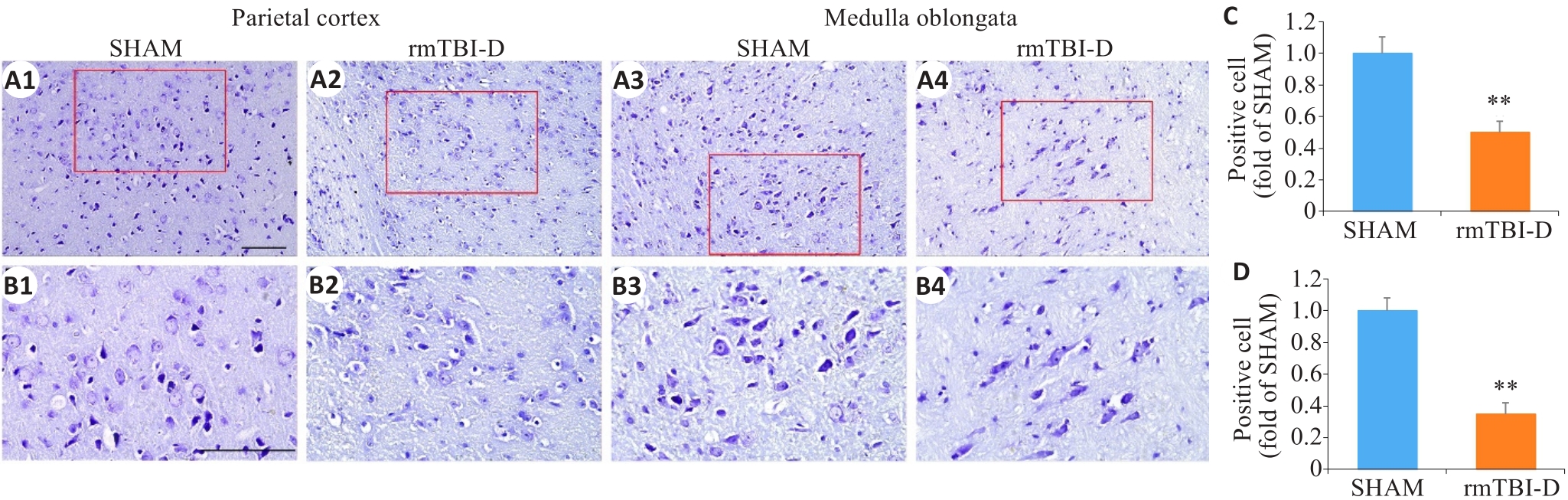

Fig.3 Loss of Nissl bodies in the neurons in the parietal cortex and medulla oblongata of the mice that did not survive rmTBI. The figures in the lower panel (B1-B4; ×40, scale bar=100 μm) are enlarged views of the boxed areas in A1-A4 (×20, scale bar=100 μm). C, D: Statistical analysis of positive cells in the parietal cortex (C) and medulla oblongata (D) (n=6). **P<0.01 vs sham group.

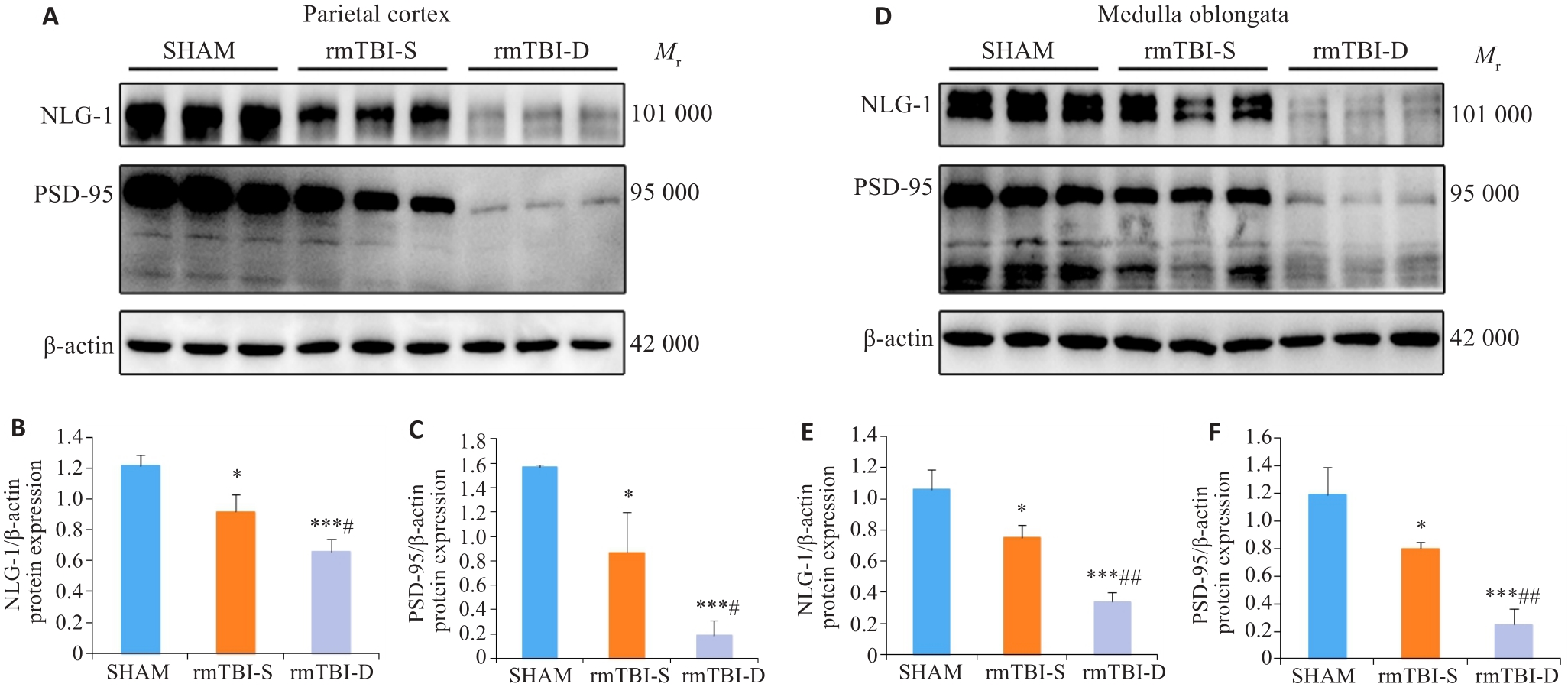

Fig.4 Western blotting of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the parietal cortex and medulla oblongata of the mice. A-C: rmTBI decreases the expression levels of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the parietal cortex, and their expression levels are lower in the mice that died after rmTBI (rmTBI-D group) than in the survivors (rmTBI-S group). D-F: rmTBI decreases the expression levels of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the medulla oblongata, and their expression levels are lower in rmTBI-D than in rmTBI-S group. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs sham group, #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs rmTBI-S group (n=3).

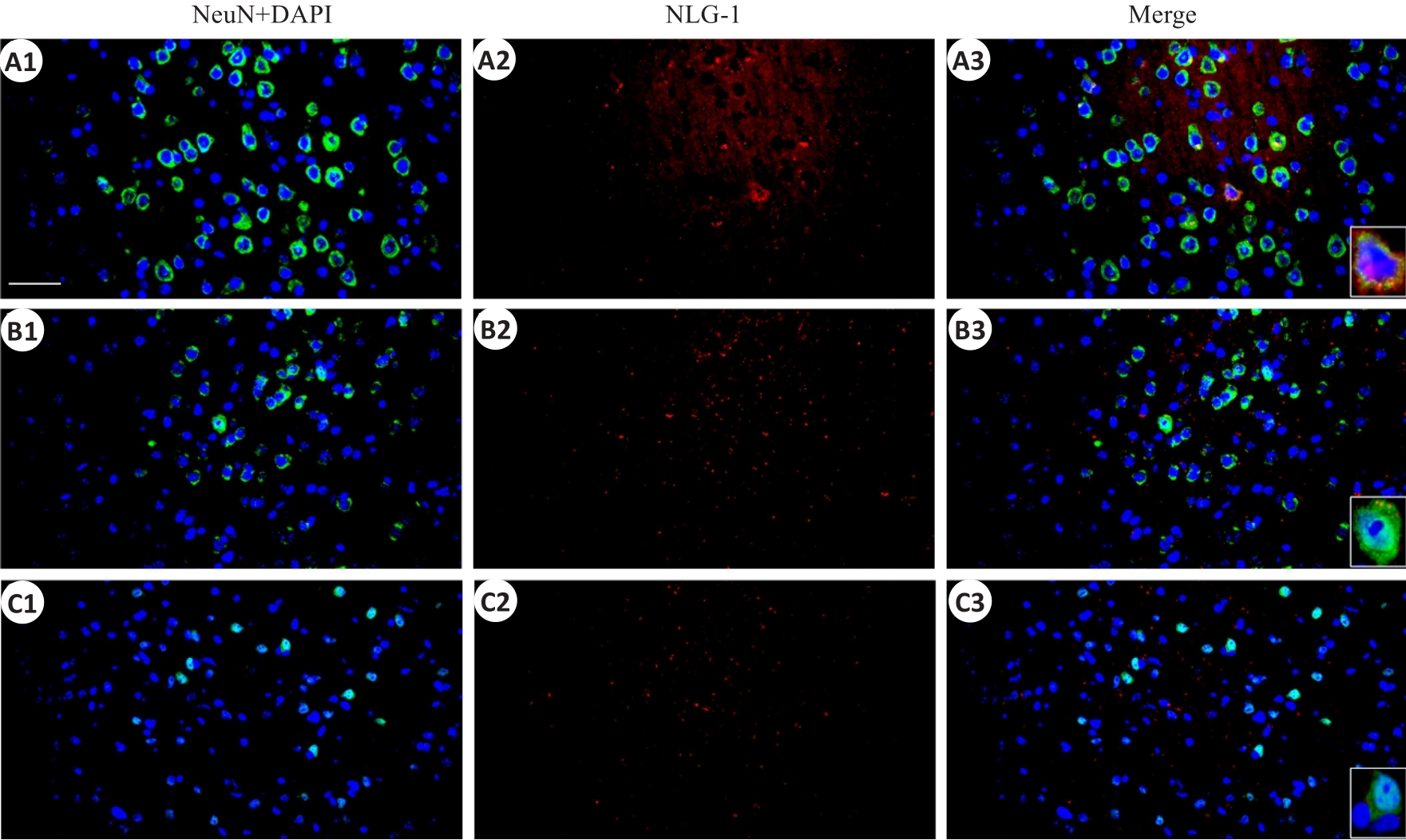

Fig.5 Immunofluorescent co-expression of NLG-1 and neuronal marker NeuN in the parietal cortex (×40, scale bar=100 μm). A1-A3: Sham group; B1-B3: rmTBI-S group; C1-C3: rmTBI-D group; NeuN,DAPI and NLG-1 present green,blue and red fluorescence rspectively.

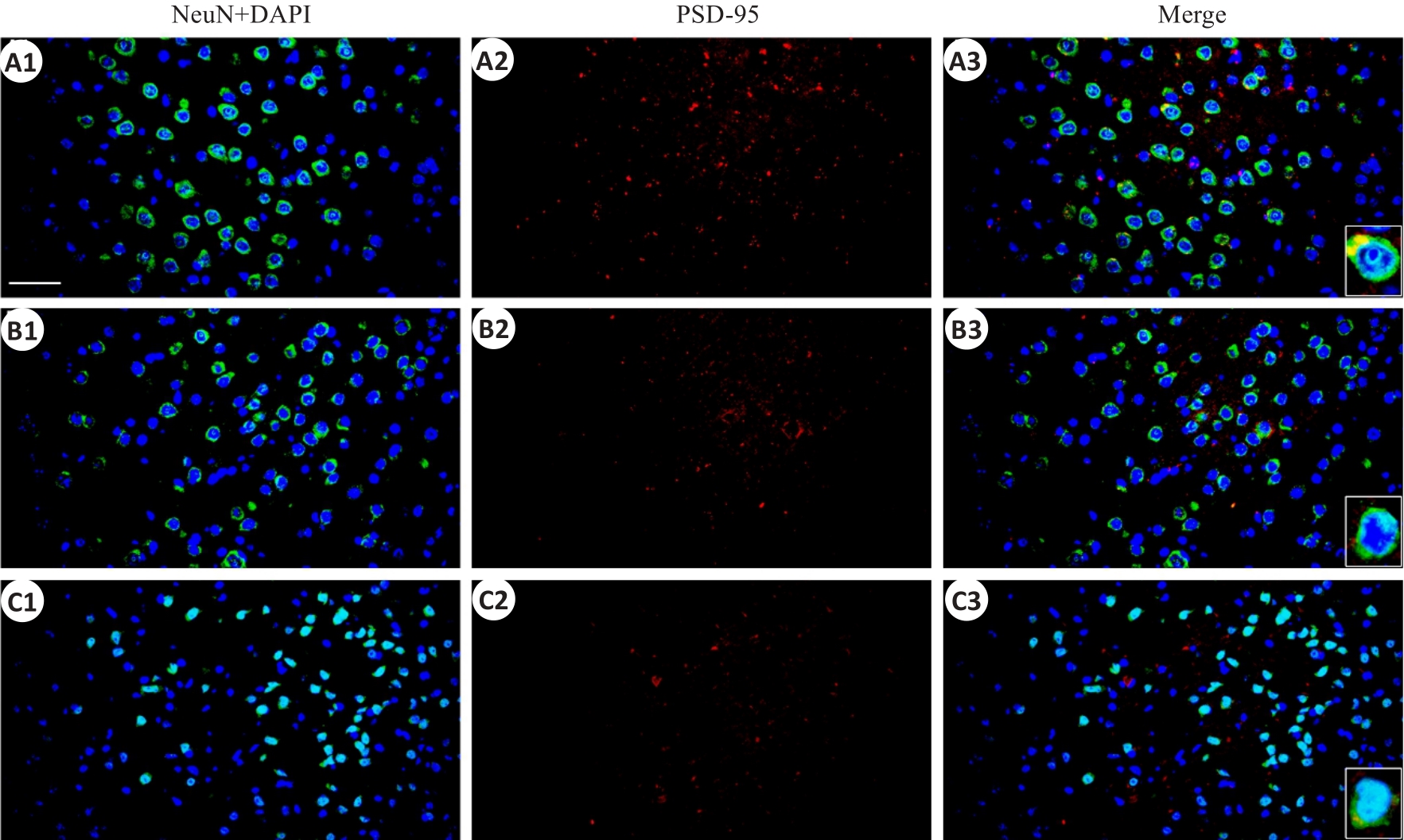

Fig.6 Immunofluorescent co-expression of PSD-95 and NeuN in the parietal cortex (×40, scale bar=100 μm).A1-A3: the sham group; B1-B3: rmTBI-S group; C1-C3: rmTBI-D group; PSD-95 presents red fluorescence.

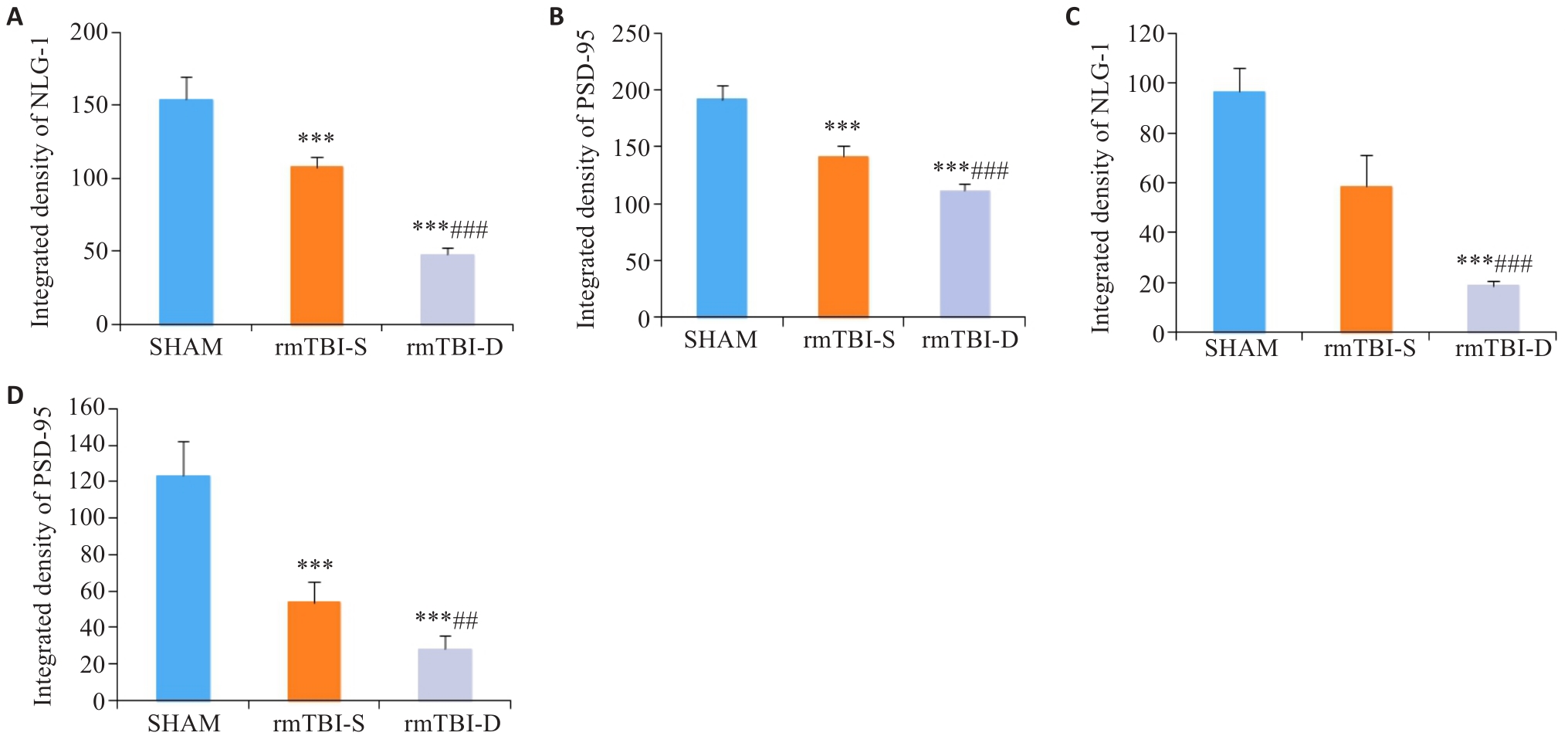

Fig.7 Statistical analysis of immunofluorescence intensity of NLG-1 and PSD-95. A, B: rmTBI decreases the integrated densities of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the parietal cortex, which are lowered in rmTBI-D group than in rmTBI-S group. C, D: rmTBI decreases the integrated densities of NLG-1 and PSD-95 in the medulla oblongata, which are lower in rmTBI-D group than in rmTBI-S group. ***P<0.001 vs sham group, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs rmTBI-S group (n=8).

| 1 | 隋立森, 余佳彬, 姜晓丹. 大鼠创伤性颅脑损伤后脑室下区内源性神经干细胞的增殖与分化[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2016, 36(8): 1094-9. |

| 2 | Skrifvars MB, Luethi N, Bailey M, et al. The effect of recombinant erythropoietin on long-term outcome after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2023, 49(7): 831-9. |

| 3 | Ratliff WA, Qubty D, Delic V, et al. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury and transcription factor modulation[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2020, 37(17): 1910-7. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2020.7005 |

| 4 | Kelly JP, Priemer DS, Perl DP, et al. Sports concussion and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: finding a path forward[J]. Ann Neurol, 2023, 93(2): 222-5. DOI: 10.1002/ana.26566 |

| 5 | Manley G, Gardner AJ, Schneider KJ, et al. A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2017, 51(12): 969-77. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097791 |

| 6 | Kawata K, Rubin LH, Wesley L, et al. Acute changes in plasma total tau levels are independent of subconcussive head impacts in college football players[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2018, 35(2): 260-6. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2017.5376 |

| 7 | Gold EM, Vasilevko V, Hasselmann J, et al. Repeated mild closed head injuries induce long-term white matter pathology and neuronal loss that are correlated with behavioral deficits[J]. ASN Neuro, 2018, 10: 1759091418781921. DOI: 10.1177/1759091418781921 |

| 8 | Greco T, Ferguson L, Giza C, et al. Mechanisms underlying vulnerabilities after repeat mild traumatic brain injuries[J]. Exp Neurol, 2019, 317: 206-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.01.012 |

| 9 | Omalu BI, Bailes J, Hammers JL, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, suicides and parasuicides in professional American athletes: the role of the forensic pathologist[J]. Am J Forensic Med Pathol, 2010, 31(2): 130-2. DOI: 10.1097/paf.0b013e3181ca7f35 |

| 10 | McMillan TM, Weir CJ, Wainman-Lefley J. Mortality and morbidity 15 years after hospital admission with mild head injury: a prospective case-controlled population study[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2014, 85(11): 1214-20. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307279 |

| 11 | Wenker IC, Abe C, Viar KE, et al. Blood pressure regulation by the rostral ventrolateral medulla in conscious rats: effects of hypoxia, hypercapnia, baroreceptor denervation, and anesthesia[J]. J Neurosci, 2017, 37(17): 4565-83. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.3922-16.2017 |

| 12 | Song JY, Ichtchenko K, Südhof TC, et al. Neuroligin 1 is a postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecule of excitatory synapses[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1999, 96(3): 1100-5. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1100 |

| 13 | Levinson JN, Chéry N, Huang K, et al. Neuroligins mediate excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation: involvement of PSD-95 and neurexin-1beta in neuroligin-induced synaptic specificity[J]. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280(17): 17312-9. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.m413812200 |

| 14 | Zhao JY, Duan XL, Yang L, et al. Activity-dependent synaptic recruitment of neuroligin 1 in spinal dorsal horn contributed to inflammatory pain[J]. Neuroscience, 2018, 388: 1-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.06.047 |

| 15 | Coley AA, Gao WJ. PSD95: a synaptic protein implicated in schizophrenia or autism[J]? Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2018, 82: 187-94. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.016 |

| 16 | Petkova-Tuffy A, Gödecke N, Viotti J, et al. Neuroligin-1 mediates presynaptic maturation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling[J]. BMC Biol, 2021, 19(1): 215. DOI: 10.1186/s12915-021-01145-7 |

| 17 | Dinda B, Dinda M, Kulsi G, et al. Therapeutic potentials of plant iridoids in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: a review[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2019, 169: 185-99. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.03.009 |

| 18 | Cai WM, Wang GJ, Wu H, et al. Identifying traumatic brain injury (TBI) by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy in a mouse model[J]. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2022, 274: 121099. DOI: 10.1016/j.saa.2022.121489 |

| 19 | Flierl MA, Stahel PF, Beauchamp KM, et al. Mouse closed head injury model induced by a weight-drop device[J]. Nat Protoc, 2009, 4(9): 1328-37. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2009.148 |

| 20 | Lasry O, Liu EY, Powell GA, et al. Epidemiology of recurrent traumatic brain injury in the general population: a systematic review[J]. Neurology, 2017, 89(21): 2198-209. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000004671 |

| 21 | Wall SE, Williams WH, Cartwright-Hatton S, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction following repeat concussions in jockeys[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2006, 77(4): 518-20. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.061044 |

| 22 | Iverson GL, Echemendia RJ, Lamarre AK, et al. Possible lingering effects of multiple past concussions[J]. Rehabil Res Pract, 2012, 2012: 316575. DOI: 10.1155/2012/316575 |

| 23 | Hunzinger KJ, Law CA, Elser H, et al. Associations between head injury and subsequent risk of falls: results from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study[J]. Neurology, 2023, 101(22): e2234-e2242. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000207949 |

| 24 | Huynh LM, Burns MP, Taub DD, et al. Chronic neurobehavioral impairments and decreased hippocampal expression of genes important for brain glucose utilization in a mouse model of mild TBI[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2020, 11: 556380. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2020.556380 |

| 25 | Zohar O, Schreiber S, Getslev V, et al. Closed-head minimal traumatic brain injury produces long-term cognitive deficits in mice[J]. Neuroscience, 2003, 118(4): 949-55. DOI: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00048-4 |

| 26 | Tsenter J, Beni-Adani L, Assaf Y, et al. Dynamic changes in the recovery after traumatic brain injury in mice: effect of injury severity on T2-weighted MRI abnormalities, and motor and cognitive functions[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2008, 25(4): 324-33. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2007.0452 |

| 27 | Wang YL, Wang L, Xu W, et al. Paraventricular thalamus controls consciousness transitions during propofol anaesthesia in mice[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2023, 130(6): 698-708. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.01.016 |

| 28 | Dewitt DS, Perez-Polo R, Hulsebosch CE, et al. Challenges in the development of rodent models of mild traumatic brain injury[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2013, 30(9): 688-701. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2012.2349 |

| 29 | Verley DR, Torolira D, Hessell BA, et al. Cortical neuromodulation of remote regions after experimental traumatic brain injury normalizes forelimb function but is temporally dependent[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2019, 36(5): 789-801. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2018.5769 |

| 30 | Ong LK. Beyond the primary infarction: focus on mechanisms related to secondary neurodegeneration after stroke[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(24): 16024. DOI: 10.3390/ijms232416024 |

| 31 | Varoqueaux F, Aramuni G, Rawson RL, et al. Neuroligins determine synapse maturation and function[J]. Neuron, 2006, 51(6): 741-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.003 |

| 32 | Cao C, Wang LW, Zhang J, et al. Neuroligin-1 plays an important role in methamphetamine-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity[J]. Toxicol Lett, 2022, 361: 1-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.03.007 |

| 33 | Camporesi E, Lashley T, Gobom J, et al. Neuroligin-1 in brain and CSF of neurodegenerative disorders: investigation for synaptic biomarkers[J]. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2021, 9(1): 19. DOI: 10.1186/s40478-021-01119-4 |

| 34 | Lai XP, Yu XJ, Qian H, et al. Chronic alcoholism-mediated impairment in the medulla oblongata: a mechanism of alcohol-related mortality in traumatic brain injury[J]? Cell Biochem Biophys, 2013, 67(3): 1049-57. DOI: 10.1007/s12013-013-9603-y |

| 35 | Levy AM, Gomez-Puertas P, Tümer Z. Neurodevelopmental disorders associated with PSD-95 and its interaction partners[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(8): 4390. (编辑:吴锦雅) |

| [1] | . Chaihu Guizhi decoction produces antidepressant-like effects via sirt1-p53 signaling pathway [J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2021, 41(3): 399-405. |

| [2] | . [J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2013, 33(04): 528-. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||