2. 儿童发育疾病研究教育部重点实验室, 重庆 400014;

3. 儿童发育重大疾病国家国际科技合作基地, 重庆 400014;

4. 儿科学重庆市重点实验室, 重庆 400014

2. Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Child Development and Critical Disorders, Chongqing 400014, China;

3. China International Science and Technology Cooperation Base of Child development and Critical Disorders, Chongqing 400014, China;

4. Chongqing Key Laboratory of Pediatrics, Chongqing 400014, China

患有先天性心脏病需要进行心脏手术的儿童,必须在手术前和手术后进行反复的经胸超声心动图(TTE)检测。但是,由于恐惧和焦虑等原因,儿童常常难以配合检查。因此,为了使患儿体验更好,TTE程序更有效、准确,接受TTE的儿童有必要接受镇静以减轻其焦虑感及运动伪影。然而,在ICU以外的地区,可用于小儿的镇静剂非常有限,众多药物均不建议用于儿童[1]。

右美托嘧啶,一种高度选择性的α2激动剂,是一种具有镇痛作用的新型镇静剂,无呼吸抑制作用,可模拟自然的非快速动眼睡眠[2-3],可以为儿童提供安全有效的镇静。如作为择期手术的辅助药物[4]和用于MRI或TTE的镇静剂[5-6]。

在临床实践中,我们发现心脏手术前后的患儿镇静时需要右美托嘧啶剂量不同,先天性紫绀性心脏病和非紫绀性先天性心脏病患儿需要的剂量也不同。但是,目前尚无关于这些差异的研究。目前关于右美托嘧啶镇静进行研究多关注于某一固定剂量应用于某一手术[7-8]或与某一全麻药物合用[9]后的有效性与安全性,尚无采用滴定法测量有效量的研究[10-12],也尚无对比心脏手术前后用药剂量差异的研究。本文目的即在于确定先天性非紫绀性心脏病患儿在经历心脏手术前后镇静需要的右美托嘧啶剂量以及相关不良反应的发生率,为临床实践提供更令人信服的证据。

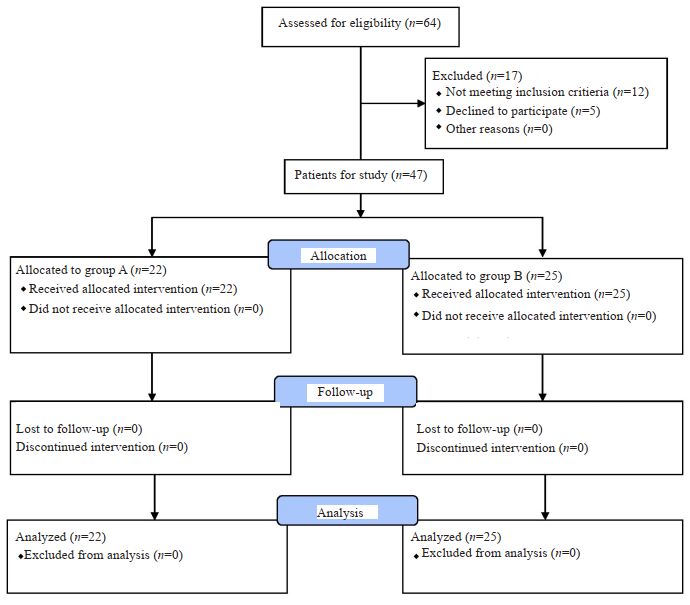

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象本项研究是在重庆医科大学附属儿童医院进行的,已获得重庆重庆医科大学附属儿童医院伦理审查委员会批准(文件号:2016124),并在chictr.org.cn上进行了注册(ChiCTR-OPC-17012665)。收集我院2017年9月18日~2017年11月20日之间,患有非紫绀性先天性心脏病,需要进行TTE的患儿64名。根据是否经历过行手术将患儿分为术前组(A组)、术后组(B组)。5名儿童的父母拒绝参加这项研究,7名儿童不符合纳入标准,A组中有5名儿童因为检查后确诊未患心脏病而未纳入(图 1)。所有患儿均在父母的陪同下完成本实验。纳入标准:年龄在3岁以下;ASA分级Ⅰ~Ⅲ级;计划在镇静剂后接受TTE;,患有先天性非紫绀性心脏病;即将接受心脏手术或接受心脏手术后1月。排除标准:患儿监护人拒绝参与;对任何研究药物成分过敏;鼻腔分泌物过多;鼻结构异常;肝或肾功能不全;心律不齐;呼吸道炎症;早产儿;21三体性综合征;正在使用β受体阻滞剂或地高辛。

|

图 1 流程图 Fig.1 Flowchart of patient enrollment |

患儿禁食至少1 h后,由不参与数据收集的麻醉护士给予鼻内右美托嘧啶。给药方法:用1 mL注射器将指定剂量的未稀释的右美托嘧啶滴入两个鼻孔,同时轻捏患儿鼻翼以增加吸收。患儿平躺在父母的怀抱,保持仰卧姿势1~2 min。接下来由不知道药物剂量的麻醉医生评估镇静效果,每5 min评定1次,评估依据为(MOAA/S)。

镇静成功的判断标准如下:镇静成功:给药后30 min内MOAA/S小于或等于3;镇静失败:30 min后,患儿MOAA/S评分大于3,或者TTE时由于患儿体动而无法完成检查。

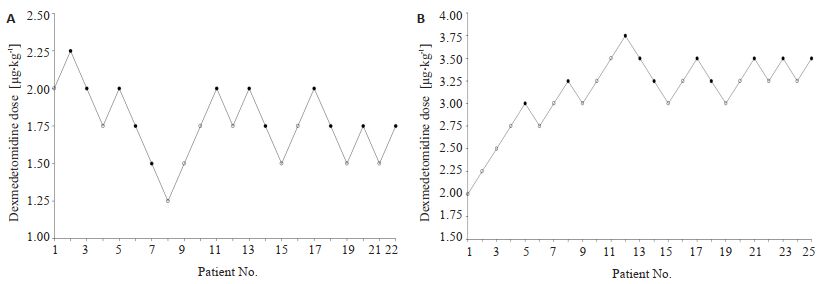

1.2.2 剂量确定方法每位患儿的用药剂量由改良序贯法[13-15]确定。将两组起始剂量均设为2.0 μg/kg,两个患儿用药间隔为0.25 μg/kg。后续受试者的右美托嘧啶剂量根据前一受试者的效果确定。如果镇静失败,则下一位患者右美托嘧啶的剂量增加0.25 μg/kg。如果患儿镇静成功,则下一位患者右美托嘧啶的剂量减少0.25 μg/kg,当每组有6个由失败到成功的转折点时即可终止实验[14-15]。

1.2.3 监测从给药(基线)开始,使用便携式监护仪连续监测心率(HR)和血氧饱和度(SpO2),每5 min测量一次呼吸频率(RR)和无创血压(NBP),直到出院为止。镇静起效时间定义为从给药开始到镇静满意时间的时间,苏醒时间为从镇静成功到醒来的时间,心动过缓和低血压分别定义为心率和血压降低幅度超过基线的20%。

1.2.4 补救措施本实验中如果镇静失败,将对患者施加一次额外的“补救”剂量的右美托嘧啶(鼻内1 μg/kg),以便患儿完成检查。如果补救镇静再次失败,临床医生则根据自己经验采取进一步措施。在整个研究过程中,TEE技师和孩子的监护人对右美托嘧啶剂量均不知情。两组之间的其他变量(例如环境噪声,照明,室温)相同。

1.2.5 离院标准完成TTE检查后,将患儿转移到恢复室继续观察,直到满足离院标准。离院标准为MAS评分≥9。在接下来的24 h内,我们仍会随访每位患儿。所有的观察和数据记录均由不知道患儿确切剂量的麻醉医生实施。

1.3 统计分析所有数据均使用R软件(版本3.2.5)进行分析,P < 0.05认为差异具有统计学意义。ED50计算方法为所有失败到成功转折的中点的平均值[14]。此外,我们还使用保序回归重新计算了ED50和ED95,用bootstrapping算法计算了95%置信区间[13]。

2 结果最终共有47位受试者成功完成了研究,A组共纳入22名受试者(7名男性;年龄:13.8±6.4月;体质量:9.1±2.4 kg)(图 2A)。B组招募了25名受试者(10名男性;年龄:15.8±5.7月;体质量:9.3±2.7 kg)(图 2B)。表 1列出了人口统计学变量。A组和B组之间没有差异(P>0.05)。两组的起效时间,检查时间和苏醒时间均无差异(P> 0.05,表 2)。表 3列出了两组患者具体患病情况。

|

图 2 两组组患者用药剂量 Fig.2 Dexmedetomidine dose in each patient in group A and B. A successful dose is indicated by a solid circle, and a failed dose by an open circle. |

| 表 1 人口学资料 Tab.1 Demographic data of the patients in the two groups |

| 表 2 两组的起效时间,检查时间和苏醒时间的比较 Tab.2 Sedation induction time and wake-up time after dexmedetomidine administration in the two groups (Mean±SD) |

| 表 3 患儿所患心脏病种类 Tab.3 Types of cardiac abnormalities in the two groups (n) |

术前组的ED50为1.84μg/kg(95%CI,1.68~2.00μg/kg),术后组为3.38 μg/kg(95%CI,3.21~3.54 μg/kg)(P < 0.05,表 4)。基于保序回归的计算结果:术前组的ED50和ED95值分别为1.79 μg/kg(95%CI,1.49~2.00 μg/kg)和2.18 μg/kg(95%CI,1.96~2.23 μg/kg);术后组ED50和ED95值分别为3.32 μg/kg(95%CI,3.08~3.50 μg/kg)和3.68 μg/kg(95%CI,3.47~3.73 μg/kg)(P < 0.01,表 4)。

| 表 4 两种计算方法下患儿的ED50 Tab.4 Dose-response data of intranasal dexmedetomidine administration for TTE sedation in the two groups derived by the Dixon-Massey up-and-down sequential allocation method and isotonic regression |

此外,我们在实验中发现A组和B组的SPO2均没有明显变化,B组的SPO2略有增加。两组HR和RR略有下降,但不超过基线的20%。A组有1名儿童经历了心动过缓。在24 h的研究期间,两组均未观察到其他不良事件,例如呼吸抑制、反流误吸等。

3 讨论在本研究中,我们使用Dixon序贯法评估并比较了右美托嘧啶滴鼻镇静用于非紫绀性先天性心脏病患儿心脏手术后前后的ED50及安全性。相比于其他方法,Dixon序贯法需要较少的样本量即可算出较为精确的ED50。此外本文还运用保序回归法估算了ED50及ED95。

增加剂量可以提高镇静的成功率,然而,不良反应发生率也会随药量的增加而增加[16-20]。对于经历过心脏手术的患儿来说,手术可能修复了潜在的分流,这会减少右美托嘧啶的需要量。但是在另一方面,接受过手术的儿童会更加惧怕医院场景,检查过程中会更加不愉快,从而需要使用更高剂量的镇静剂。因此,明确心脏手术前后患儿的用药剂量在临床上显得比较重要。

由于各种实验条件和人群不同,鼻内右美托嘧啶的有效剂量在婴幼儿中仍然不确定。右美托嘧啶滴鼻已被广泛用于儿童各种检查的镇静,文献报道的剂量范围多在1~3 μg/kg[16-26]。研究表明使用1 μg/kg的右美托嘧啶滴鼻可使53%~57%的儿童获得满意镇静[23-24],这与本研究结果有一定差距我们认为可能与研究人群、年龄以及检查种类不同有关。还有报告称,与较低剂量相比,2 μg/kg的剂量可取的更满意的镇静效果,并且不会增加心血管方面的副作用[25]。

目前没有证据表明除单心室先心病外,不同类型先心病的药代动力学有不同[27-28]。此外,有研究显示先天性非紫绀性心脏病患儿和先天性紫绀性心脏病患儿的药代动力学可能会有所不同[29]。因此,在本研究中我们仅招募了患有非紫绀性先天性心脏病的儿童,且未根据具体心脏病的类型进行更进一步的亚组分析。

本研究发现,不同人群需要的镇静剂量是不一样,术后组的儿童需要更多的右美托嘧啶才能获得足够的镇静作用,这可能是之前研究差异性的来源之一。我们认为可能是药物耐受性,焦虑以及由伤口引起的不适等原因造成的。

对于心脏手术后恢复期的患者,术后镇静是必要的。重症监护室(ICU)往往会使用镇静剂,因为它可以减轻因手术,插管,机械通气,吸痰等操作引起的不适和焦虑。药理学研究表明,连续服用又美可以产生药物耐受性[22]。迄今为止,关于右美托嘧啶耐受性发生率的数据有限。许多中心根据经验建议将右美托嘧啶的使用时间限制为48 h或更短[26]。

在本研究中,A组和B组的HR和RR均降低了,而SPO2却没有。先前的研究表明,右美托嘧啶对血压的影响呈双相性[30]。在低浓度下,右美托嘧啶的主要作用是通过集中介导交感神经并抑制交感神经的神经传递来降低血压[31-33]。由于大多数儿童都会因为紧张而心动过速、血压增高,因此他们可能反而受益。

本研究是通过Dixon序贯法获得ED50,该方法需要较少样本量即可。因此,本研究中ED95[22]的计算仅为估算值,进一步的研究需要大的样本量。此外,本研究的局限性还包括一些潜在的混杂因素,例如镇静前一晚的睡眠质量可能会干扰该研究。

综上所述,右美托嘧啶是一种合适的用于TTE镇静剂,具有许多优点,如恢复时间短暂、不会产生严重的副作用。患有非紫绀性先天性心脏病的儿童在心脏手术前需要较少的右美托嘧啶即可完成TTE手术,右美托嘧啶对这些患儿来说也比较安全。当这些患儿经历了心脏修复术后需要较大剂量的镇静剂才能获得满意的镇静效果。临床实践中,当我们选择右美托嘧啶滴鼻用于儿童TTE镇静时,应考虑儿童是否有手术史。

| [1] |

Roberts R, Rodriguez W, Murphy D, et al. Pediatric drug labeling: improving the safety and efficacy of pediatric therapies[J]. JAMA, 2003, 290(7): 905-11. DOI:10.1001/jama.290.7.905 |

| [2] |

Coté CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: analysis of medications used for sedation[J]. Pediatrics, 2000, 106(4): 633-44. DOI:10.1542/peds.106.4.633 |

| [3] |

Karian VE, Burrows PE, Zurakowski D, et al. Sedation for pediatric radiological procedures: analysis of potential causes of sedation failure and paradoxical reactions[J]. Pediatr Radiol, 1999, 29(11): 869-73. DOI:10.1007/s002470050715 |

| [4] |

Mandell GA, Majd M, Shalaby-Rana EI, et al. Society of nuclear medicine procedure guideline for pediatric sedation in nuclear medicine[J]. J Nucl Med, 2003, 44: 173-4. |

| [5] |

Mahmoud M, Gunter J, Donnelly LF, et al. A comparison of dexmedetomidine with propofol for magnetic resonance imaging sleep studies in children[J]. Anesth Analg, 2009, 109(3): 745-53. DOI:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181adc506 |

| [6] |

Mahmoud M, Radhakrishman R, Gunter J, et al. Effect of increasing depth of dexmedetomidine anesthesia on upper airway morphology in children[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2010, 20(6): 506-15. DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03311.x |

| [7] |

王风. 右美托嘧啶在先心病影像学检查时应用的观察[J]. 医药论坛杂志, 2016, 37(3): 139-40. |

| [8] |

岳静.右美托嘧啶用于儿童扁桃体、腺样体切除术术后镇静效果的临床观察[D].长春: 吉林大学, 2013. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10183-1013194281.htm

|

| [9] |

杨志攀. 右美托嘧啶预防七氟烷小儿全身麻醉术后躁动的临床分析[J]. 临床合理用药杂志, 2014, 7(27): 105-6. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-3296.2014.27.075 |

| [10] |

乔永平, 刘轶宁, 黄丹青. 支气管镜检查中应用右美托咪定镇静对患儿气道反应和心血管反应的影响观察[J]. 中国实用医药, 2020, 15(1): 126-7. |

| [11] |

马彦玲, 杜鹏. 右美托咪定与氯胺酮在儿童短小手术麻醉后痛觉过敏及苏醒躁动的应用研究[J]. 检验医学与临床, 2019, 16(21): 3200-2. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-9455.2019.21.040 |

| [12] |

刘剑霞, 杜敏, 刘巍, 等. 右美托咪定联合氯胺酮滴鼻用于小儿术前镇静的效果评估[J]. 重庆医科大学学报, 2017, 42(12): 1671-5. |

| [13] |

Pace NL, Stylianou MP. Advances in and limitations of up-anddown methodology: a précis of clinical use, study design, and dose estimation in anesthesia research[J]. Anesthesiology, 2007, 107(1): 144-52. DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000267514.42592.2a |

| [14] |

Burlacu CL, Gaskin P, Fernandes A, et al. A comparison of the insertion characteristics of the laryngeal tube and the laryngeal mask airway: a study of the ED50 propofol requirements[J]. Anaesthesia, 2006, 61(3): 229-33. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04442.x |

| [15] |

Dixon WJ. Staircase bioassay: the up-and-down method[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 1991, 15(1): 47-50. |

| [16] |

Deutsch E, Tobias JD. Hemodynamic and respiratory changes following dexmedetomidine administration during general anesthesia: sevoflurane vs desflurane[J]. Pediatr Anesth, 2007, 17(5): 438-44. DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02139.x |

| [17] |

Mason KP, Lubisch NB, Robinson F, et al. Intramuscular dexmedetomidine sedation for pediatric MRI and CT[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2011, 197(3): 720-5. DOI:10.2214/AJR.10.6134 |

| [18] |

Petroz GC, Sikich N, James M, et al. A phase I, two-center study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine in children[J]. Anesthesiology, 2006, 105(6): 1098-110. DOI:10.1097/00000542-200612000-00009 |

| [19] |

Tokuhira N, Atagi K, Shimaoka H, et al. Dexmedetomidine sedation for pediatric post-Fontan procedure patients[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2009, 10(2): 207-12. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e31819a3a3e |

| [20] |

Peng K, Wu SR, Ji FH, et al. Premedication with dexmedetomidine in pediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2014, 69(11): 777-86. DOI:10.6061/clinics/2014(11)12 |

| [21] |

Li BL, Ni J, Huang JX, et al. Intranasal dexmedetomidine for sedation in children undergoing transthoracic echocardiography study: a prospective observational study[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2015, 25(9): 891-6. DOI:10.1111/pan.12687 |

| [22] |

Miller JW, Divanovic AA, Hossain MM, et al. Dosing and efficacy of intranasal dexmedetomidine sedation for pediatric transthoracic echocardiography: a retrospective study[J]. J Can D'anesthesie, 2016, 63(7): 834-41. DOI:10.1007/s12630-016-0617-y |

| [23] |

Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, et al. A comparison of intranasal dexmedetomidine and oral midazolam for premedication in pediatric anesthesia: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial[J]. Anesth Analg, 2008, 106(6): 1715-21. DOI:10.1213/ane.0b013e31816c8929 |

| [24] |

Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, et al. Optimal timing for the administration of intranasal dexmedetomidine for premedication in children[J]. Anaesthesia, 2010, 65(9): 922-9. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06453.x |

| [25] |

Wang SS, Zhang MZ, Sun Y, et al. The sedative effects and the attenuation of cardiovascular and arousal responses during anesthesia induction and intubation in pediatric patients: a randomized comparison between two different doses of preoperative intranasal dexmedetomidine[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2014, 24(3): 275-81. DOI:10.1111/pan.12284 |

| [26] |

Mekitarian Filho E, Robinson F, de Carvalho WB, et al. Intranasal dexmedetomidine for sedation for pediatric computed tomography imaging[J]. J Pediatr, 2015, 166(5): 1313-5. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.01.036 |

| [27] |

Potts AL, Warman GR, Anderson BJ. Dexmedetomidine disposition in children: a population analysis[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2008, 18(8): 722-30. DOI:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02653.x |

| [28] |

Talke P, Li J, Jain U, et al. Effects of perioperative dexmedetomidine infusion in patients undergoing vascular surgery. The Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group[J]. Anesthesiology, 1995, 82(3): 620-33. DOI:10.1097/00000542-199503000-00003 |

| [29] |

Lynn AM, Nespeca MK, Bratton SL, et al. Ventilatory effects of morphine infusions in cyanotic versus acyanotic infants after thoracotomy[J]. Paediatr Anaesth, 2003, 13(1): 12-7. DOI:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00959.x |

| [30] |

Paris A, Tonner PH. Dexmedetomidine in anaesthesia[J]. Curr Opin Anesthesiol, 2005, 18(4): 412-8. DOI:10.1097/01.aco.0000174958.05383.d5 |

| [31] |

Hein L, Limbird LE, Eglen RM, et al. Gene substitution/knockout to delineate the role of alpha 2-adrenoceptor subtypes in mediating central effects of catecholamines and imidazolines[J]. Ann NY Acad Sci, 1999, 881: 265-71. DOI:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09368.x |

| [32] |

MacMillan LB, Hein L, Smith MS, et al. Central hypotensive effects of the α2a-adrenergic receptor subtype[J]. Science, 1996, 273(5276): 801-3. DOI:10.1126/science.273.5276.801 |

| [33] |

Link RE, Desai KH, Hein L, et al. Cardiovascular regulation in mice lacking α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes b and C[J]. Science, 1996, 273(5276): 803-5. DOI:10.1126/science.273.5276.803 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40