2. 四川大学华西临床医学院,四川 成都 610041;

3. 重庆医科大学附属第二医院肝胆外科,重庆 400016;

4. 重庆市潼南区人民医院肝胆外科,重庆 402660

2. West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China;

3. Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China;

4. Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, People's Hospital of Tongnan District, Chongqing 402660, China

肝纤维化是由多种慢性肝损伤引起的自愈过程。肝纤维化的特点是大量细胞外基质的沉积,导致肝组织中结缔组织的异常增殖[1]。在这个病理过程中,肝纤维化是唯一可逆的过程。因此,探讨逆转肝纤维化的方法对预防肝硬化性肝细胞癌的发生尤为重要[2]。大量研究发现,活化的肝星状细胞在肝纤维化的病理过程中发挥重要作用。维甲酸信号通路对肝星状细胞促纤维化潜力有重要的调控作用,并且认为其能够与过氧化物酶体增殖物活化受体γ (PPAR-γ)协同作用,有利于肝纤维化的逆转[3]。甲氧基欧芹酚能够抑制肝星状细胞(HSC)的活化,进而改善了硫代乙酰胺(TAA)诱导的大鼠肝损伤、纤维化和炎症[4]。因此,诱导活化的肝星状细胞凋亡是阻断肝纤维化发展的重要策略。

内质网应激是一种由未折叠蛋白反应过度激活引起的内质网稳态失衡。既往研究发现,ER-stress在诱导活化的HSCs凋亡中起着重要的调控作用。依托泊苷能够经ER-stress途径诱导人肝星状细胞的凋亡[5]。ERstress介导的自噬能够促进咖啡因诱导的肝星状细胞凋亡[6]。但是,也有研究报道,ER-stress并不能促进HSC凋亡[7]。因此,进一步研究对于阐明内质网应激在肝细胞凋亡中的作用机制显得尤为重要。

Kupffer细胞(KCs)是体内最大的巨噬细胞群,也是肝内重要的非实质细胞。由于其具有较高的可塑性,KCs能够通过改变其细胞极性,适应不同的机体内环境,并发挥不同的生物学效应[8-10]。ER-stress在调控KCs细胞极性以及下游炎症因子分泌谱方面,特别是肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α)的分泌,有着重要的意义。前期研究发现ER-stress能够促进骨髓源性巨噬细胞分泌大量TNF-α[11]。牛磺熊去氧胆酸能够通过抑制KCs内质网应激,减少KCs源性TNF-α的分泌[12]。值得注意的是,TNF-α被认为广泛参与了多种细胞凋亡过程的调控[13-15],但是ER-stress介导的KCs源性TNF-α分泌增加是否能够诱导HSC凋亡,从而逆转肝纤维化,仍未见明确报道。

在本实验中,我们观察了ER-stress介导的KCs源性TNF-α分泌增加对活化肝星状细胞凋亡的作用,并对其可能的作用机制进行了探讨,旨在找寻一种能够有效逆转肝纤维化进程的新方法。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要材料DMEM培养基、ELISA试剂盒购于Abcam。RTPCR引物由Sangon Biotech(上海)合成。TUNEL试剂盒购于Roche。CD16、结蛋白(Desmin)、肿瘤坏死因子受体(TNFR)、cleaved-caspase 8、caspase 8、cleavedcaspase 3以及caspase 3一抗抗体购于Abcam。甘油醛-3-磷酸脱氢酶(GAPDH)一抗抗体购于BOSTER Biological Technology(上海)。本研究使用的所有其他试剂均为商用分析级试剂。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 实验动物与分组雄性SD大鼠(200~300 g)由重庆医科大学实验动物中心提供。在美国国立卫生研究院指导下,对所有动物进行了人道主义护理。本研究使用的方案经重庆医科大学第二附属医院动物使用与伦理委员会(2015~2018)评审通过。按照随机数字表法,将大鼠随机分为4组:对照组(Control group,n=15):大鼠腹腔注射生理盐水(2 mg/kg),2次/周,共8周。大鼠术后给予正常饮食水。

肝纤维化组(Model group,n=15):大鼠腹腔注射40% CCl4溶液(花生油制成,2 mg/kg),2次/周,共8周。大鼠术后给予正常饮食饮水。

内质网应激组(ER-stress group,n=15):大鼠腹腔注射40% CCl4(花生油制成,2 mg/kg)溶液和衣霉素(1 mg/kg)[16],2次/周,共8周。大鼠术后给予正常饮食饮水。

KCs封闭组(Depletion group,n=15):大鼠腹腔注射40% CCl4溶液(花生油制成,2 mg/kg)和衣霉素(1 mg/kg),2次/周,共8周。经衣霉素处理后,经腹腔注射氯膦酸脂质体(50 mg/kg)[17],封闭KCs功能。大鼠术后给予正常饮食饮水。

1.2.2 分离、培养KCs根据Li等[6]提出的三步法,即IV型胶原酶消化、梯度离心和选择性粘附,分离KCs。在37 ℃,5% CO2条件下,KCs培养于含10%胎牛血清、100 U/mL青霉素G、100 U/mL链霉素的DMEM培养基中。

1.2.3 KCs、LX2共培养模型建立在37 ℃,5% CO2条件下,LX2细胞与KCs(按10:1的比例)在含10%胎牛血清、100 U/mL青霉素G、100 U/mL链霉素的DMEM中共培养24 h。收集细胞和上清液用于后续实验,随机分为4组,具体分组如下:

对照组:按上述方法分离提取对照组大鼠KCs细胞,并与LX2细胞共培养。

肝纤维化组:按上述方法分离提取肝纤维化组大鼠KCs细胞,并与LX2细胞共培养。

ER-stress组:按上述方法分离提取ER-stress组大鼠KCs细胞,并与LX2细胞共培养。

肿瘤坏死因子受体(TNFR)阻断组:在ER-stress大鼠基础上,经门静脉注射anti-ratTNFRmAb(0.35 mg/kg)后,按上述方法分离提取ER-stress组大鼠KCs细胞,并与LX2细胞共培养。

1.2.4 ELISA收集各组大鼠血清标本和KCs上清液。将抗体血清(100 µL/孔)加入到ELISA孔板中,于37 ℃反应1 h。将各组大鼠血清和KCs上清液(100 µL/孔)加入到ELISA孔板中,于37 ℃反应1 h。随后,将抗IgG抗体加入到ELISA孔板中,于37 ℃反应1 h。反应结束后,将工作液加入到ELISA孔板中,于37 ℃反应30 min。最后,将染色液加入ELISA孔板中,运用ELISA检测仪检测各孔样本中细胞因子水平。

1.2.5 免疫荧光各组细胞经4%多聚甲醛固定、0.2% Triton X-100通透、5%小牛血清封闭后,在4 ℃下,避光过夜孵育于CD16(1:200)、DESMIN(1:200)一抗抗体溶液中。然后,在37 ℃下,避光孵育于荧光二抗(1:5000)溶液中1 h。最后,在37 ℃下,避光孵育于DAPI溶液中15 min,并以抗荧光淬灭剂封片。运用荧光显微镜观察各组细胞CD16、DESMIN染色情况,并统计阳性细胞数量,进行定量分析。

1.2.6 Western blot按以下步骤进行Western blot:蛋白样品经电泳、转膜、5%小牛血清封闭后,在4 ℃下,过夜孵育于TNFR(1:1000),cleaved- caspase 8(1:1000),caspase 8(1:1000),cleaved- caspase 3(1:1000)以及caspase 3(1:1000)的一抗抗体溶液中。然后,在37 ℃下,孵育于二抗溶液中1 h。根据GAPDH表达量,对所有样本进行标准化。

1.2.7 RT-PCR按以下步骤进行RT-PCR:初始变性阶段95 ℃ 5 min,变性阶段94 ℃ 60 s,退火阶段58 ℃ 69 s,延伸阶段72 ℃ 60 s,循环40次。根据GAPDH表达量,对所有样本进行标准化。具体引物序列如下:TNF-α:F: 5'-GAGAGGCCGAGATTCACAGAG-3' R: 5'-CGG AACAAATCCAGAAGACCAG-3'; GAPDH:F: 5'-GT GGGTGAGGAGCACGTAGTC-3' R: 5'-GAGCTTCC CGTTCAGCTCTG-3'。

1.2.8 肝功能检测术后收集各组大鼠血液标本,采用全自动生化分析仪(Beckman CX7,Beckman Coulter,美国)检测血清谷氨酸转氨酶(AST)、天冬氨酸转氨酶(ALT)等肝功能指标,评价肝功能。

1.2.9 天狼星红染色石蜡切片经二甲苯脱蜡、梯度浓度乙醇洗脱后,用天狼星红液和苏木精染色,并以中性树胶封片。运用倒置显微镜观察各组肝组织染色情况,以细胞质呈红色为阳性,并统计阳性细胞数量,进行定量分析。

1.2.10 免疫组化石蜡切片经二甲苯脱蜡、梯度浓度乙醇洗脱、枸橼酸钠溶液抗原修复,山羊血清封闭后、在4 ℃下,过夜孵育于CD16(1:50 00)和DESMIN(1:4000)一抗抗体溶液。然后,石蜡切片在37 ℃下,孵育于二抗溶液中30 min。经DAB溶液染色、苏木精滴染、二甲苯脱蜡、乙醇梯度洗脱后,用中性树胶封片。运用倒置显微镜观察各组肝组织CD16、DESMIN表达情况,并统计阳性细胞数量,进行定量分析。

1.2.11 TUNEL根据TUNEL试剂盒说明书,进行TUNEL染色实验。运用倒置显微镜观察染色结果,以细胞核呈棕色为阳性,并统计TUNEL阳性细胞数量,进行定量分析。

1.3 统计学分析所有结果均采用SPSS 18.0软件(SPSS Inc,美国)进行分析。正态分布数据用均数±标准差表示,采用t检验检测各组间差异。异常分布数据以中值表示,采用秩和检验各组间检验差异。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

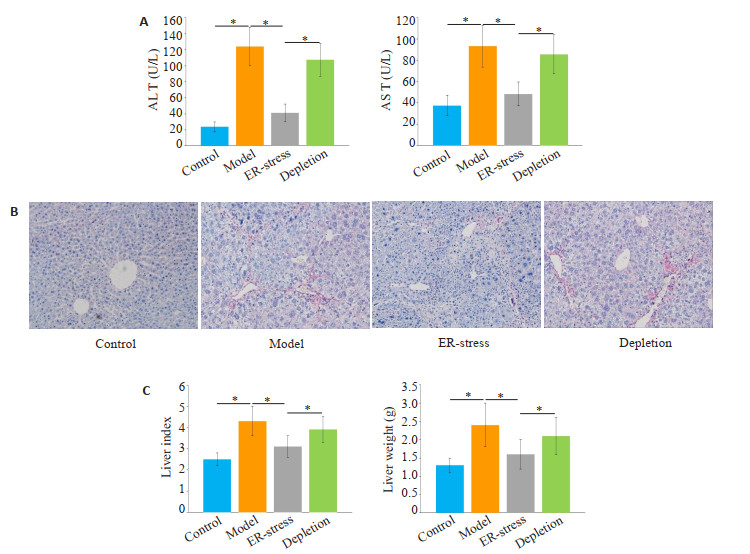

2 结果 2.1 KCs内质网应激有效的降低了大鼠肝功能标志物水平和肝纤维化程度与对照组相比,肝纤维化组的ALT和AST水平明显增加(P < 0.05,图 1A)。经衣霉素处理后,与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组的ALT和AST水平明显下降(P < 0.05)。在封闭KCs功能后,与ER-stress组相比,KCs封闭组的ALT和AST水平组显著增加(P < 0.05)。各组肝脏重量、肝脏指数变化趋势与肝功能指标相似,如图 1B所示。运用天狼星红染色检测肝纤维化程度。如图 1C所示,与对照组相比,肝纤维化组天狼星红染色阳性区域显著增加。经衣霉素处理后,与肝纤维化组相比,ERstress组天狼星红染色阳性区域显著降低。在封闭KCs功能后,与ER-stress组相比,KCs封闭组天狼星红染色阳性区域明显增加。

|

图 1 KCs内质网应激降低了大鼠肝功能标志物水平和肝纤维化程度 Fig.1 Endoplasmic reticulum stress of the KCs reduces liver function markers and liver fibrosis in rats. A: Serum AST and ALT levels in each group (*P < 0.05); B: Degree of liver fibrosis in each group (Sirius red staining, original magnification: ×400); C: Liver weight and liver index (*P < 0.05). |

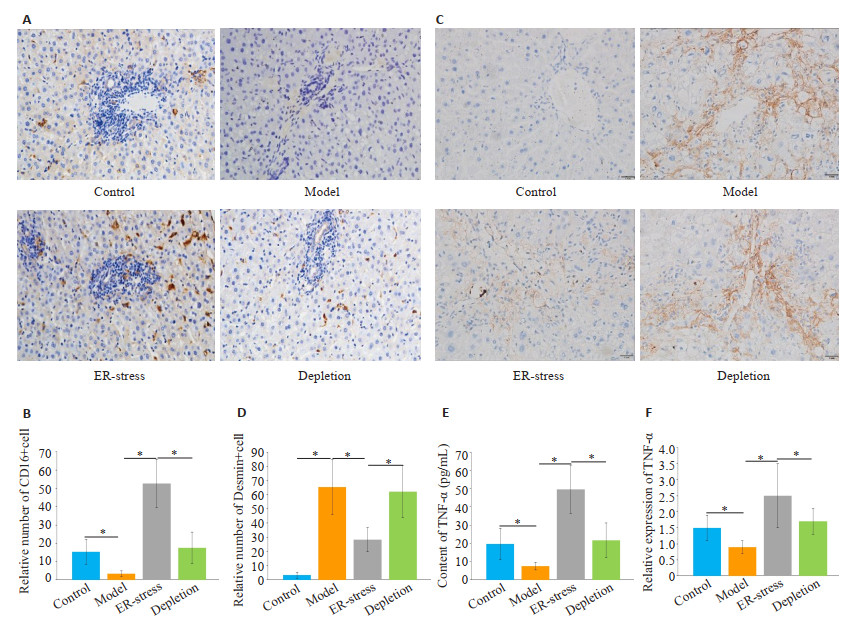

与对照组相比,肝纤维化组CD16阳性KCs数量明显降低(P < 0.05,图 2A~B)。经衣霉素处理后,与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组CD16阳性KCs数量显著增加(P < 0.05)。封闭KCs功能后,与ER-stress组相比,KCs封闭组CD16阳性KCs数量明显降低(P < 0.05)。然后,运用免疫组化染色法检测各组肝组织内活化肝星状细胞数量。与对照组相比,肝纤维化组Desmin阳性细胞数量明显增加(P < 0.05,图 2C~D)。经衣霉素处理后, 与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组Desmin阳性细胞数量显著减少(P < 0.05)。阻断KCs功能后,与ER-stress组相比,KCs封闭组Desmin阳性细胞的数量明显增加(P < 0.05)。运用ELISA和RT-PCR检测各组大鼠血清内TNF-α水平,各组TNF-α水平呈现与免疫组化相似的趋势(图 2E~F)。

|

图 2 KCs内质网应激增加了肝组织内M1型KCs数量,降低了肝组织内活化肝星状细胞数量 Fig.2 Endoplasmic reticulum stress KCs increases the number of M1 KCs and reduces the number of activated hepatic stellate cells in the liver. A: Immunohistochemical staining for detection of M1 type KC (×400); B: Number of CD16-positive cells in the liver (*P < 0.05); C: Detection of the number of active hepatic stellate cells by immunohistochemical staining (×400); D: Number of activated hepatic stellate cells in the liver (*P < 0.05); E, F: Serum level of TNF-α and its mRNA expression (*P < 0.05). |

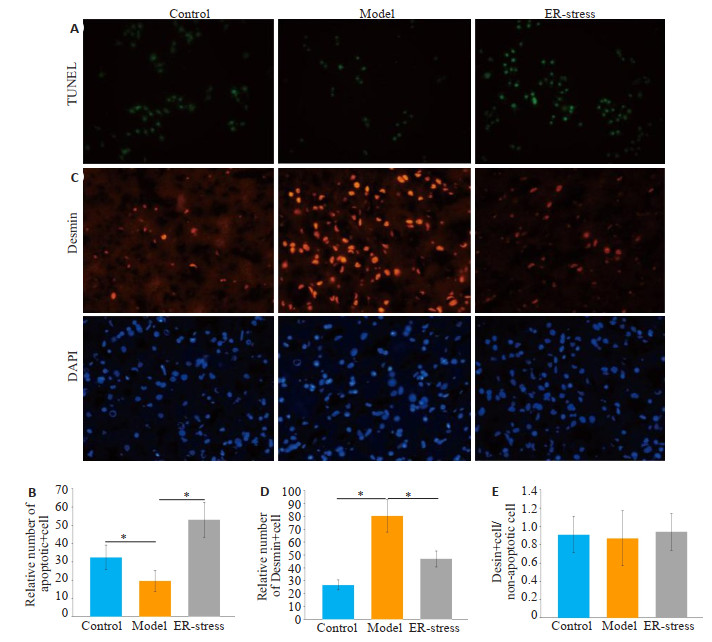

与对照组相比,肝纤维化组内凋亡LX2细胞的数量明显减少(P < 0.05,图 3A)。经衣霉素处理后,与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组内凋亡LX2细胞的数量明显增加(P < 0.05)。Desmin阳性细胞的数量在各组呈现相反的趋势(P < 0.05,图 3C)。各组Desmin阳性细胞和总非凋亡细胞比例差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,图 3E)。

|

图 3 活化肝星状细胞细胞数量下降的主要途径是KCs内质网应激诱导的细胞凋亡 Fig.3 KCs endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis is the main pathway for the decrease in the number of activated hepatic stellate cells. A: TUNEL staining for detecting apoptosis of activated hepatic stellate cells (×400); B: Relative number of apoptotic activated hepatic stellate cells in each group (*P < 0.05); C: Immunofluorescence assay of the number of activated hepatic stellate cells (×400); D: Relative number of activated hepatic stellate cells in each group (*P < 0.05); E: Proportion of Desmin-positive cells and total non-apoptotic cells. |

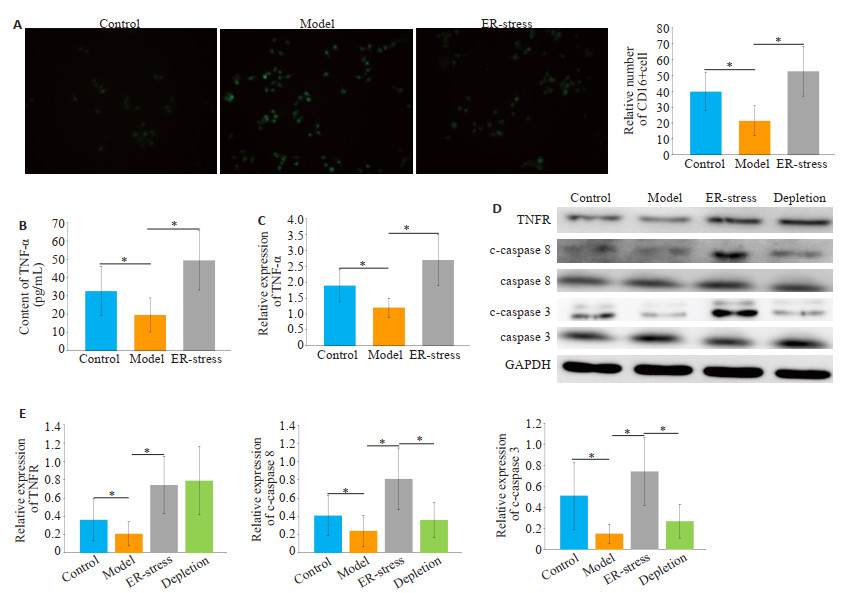

与对照组相比,肝纤维化组CD16阳性细胞数量明显降低(P < 0.05,图 4A)。经衣霉素处理后, 与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组CD16阳性细胞数量显著增加(P < 0.05)。各组KCs内TNF-α表达和mRNA水平呈现类似的趋势(图 4B)。与对照组相比,肝纤维化组KCs内TNFR1、c-caspase 8、c-caspase 3的表达明显降低(P < 0.05,图 4D)。经衣霉素处理后,与肝纤维化组相比,ER-stress组TNFR、c-caspase 8、c-caspase 3的表达明显增加(P < 0.05);经anti-rat TNFR mAb处理后,与ERstress组相比,TNFR阻断组中TNFR未见显著改变,但c-caspase 8、c-caspase 3的表达明显下降(P < 0.05)。

|

图 4 内质网应激介导的KCs源性TNF-α分泌经上调TNFR/caspase8信号通路活性诱导LX2细胞凋亡 Fig.4 Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated TNF-α secretion in KCs induces apoptosis in LX2 cells by up-regulating TNFR/caspase8 signaling pathway activity. A: Immunofluorescence detection of M1 type KCs, ×400, *P < 0.05; B, C: TNF-α expression and mRNA levels in cell supernatant, *P < 0.05; D: Western blotting detects the expression of TNFR, cleaved caspase 8, cleaved caspase 3 in each group of KCs; E: Relative expression of protein. *P < 0.05. |

肝硬化是一种以功能性肝结构被非功能肝结构逐步代替为特征的终末期肝功能紊乱[18]。值得注意的是,在肝纤维化的病理过程中,活化肝星状细胞被认为是分泌基质蛋白的肌成纤维细胞的主要细胞来源,也是肝纤维化发生的主要驱动因素[19-20]。目前,以肝星状细胞为靶点,治疗肝纤维化主要有两种理论:一种治疗方法是抑制造血干细胞的活化;另一种治疗方法是促进造血干细胞的凋亡。在我们的研究中,随着KCs内质网应激诱导的活化肝星状细胞凋亡的增加,血清AFT、ALT水平、肝纤维化程度均明显降低。与此同时,血清TNF-α水平以及mRNA水平也显著下降。这些结果表明,促进活化肝星状细胞凋亡可以减轻肝纤维化的严重程度,这与之前的一些研究一致[21]。

拟南芥能够调控非折叠蛋白反应和内质网应激介导的细胞凋亡[22]。内质网应激诱导的CHOP上调能够促进细胞凋亡[23]。近年来,内质网应激与活性肝星状细胞凋亡的关系得到了广泛的研究。目前,主流理论认为内质网应激可通过多种信号通路促进活化肝星状细胞的凋亡。Kawasaki[24]认为,当自噬受到抑制时,敲除活化肝星状细胞Hsp47基因能够引起前胶原积累,从而诱导肝星状细胞内质网应激,最终引起肝星状细胞凋亡。大麻二酚可经内质网应激途径诱导活化肝星状细胞死亡[25]。然而,也有一些研究持相反观点[7, 26],认为内质网应激不能诱导肝星状细胞凋亡。这些结果表明,内质网应激诱导活化肝星状细胞的凋亡可能有其他机制参与。TNF-α是一种重要的细胞因子,它被广泛认为参与细胞凋亡的调节。cIAP1是调节TNF-α诱导的肠上皮细胞死亡或存活所必需的[27]。一项关于心肌细胞的实验表明,TNF-α诱导的AIF上调是导致大鼠心肌细胞凋亡的关键机制[28]。因此,TNF-α有可能参与了内质网应激介导的细胞凋亡的调控。

值得注意的是,作为肝内一种重要的TNF-α分泌者[29],前期研究发现抑制KCs内质网应激可以减少肝内TNF-的α分泌[11-12]。在我们的研究中发现,经衣霉素处理后,M1型KCs数量和KCs源性TNF-α的分泌均显著增高。同时,KCs内质网应激显著降低了肝纤维化程度,降低了血清ALT、AST水平,也显著降低了肝脏中活化肝星状细胞的数量。在阻断KCs功能后,上述结果均被逆转。这些实验结果提示,通过增加KCs源性TNF-α的分泌,KCs内质网应激可以减少肝组织内活化肝星状细胞的数量。最后,我们对KCs源性TNF-α诱导活化肝星状细胞凋亡的可能研究进行了探讨。我们发现,经衣霉素处理后,活化肝星状细胞数量显著减少,细胞数量减少的主要途径是内质网应激引起的细胞凋亡。同时,活化肝星状细胞内TNFR、cleaved-caspase 8、cleaved-caspase 3的表达也显著增加。这些实验结果表明,KCs源性TNF-α分泌增加经上调TNFR/caspase 8信号通路活性促进活化肝星状细胞的凋亡。

综上所述,衣霉素诱导的内质网应激能够促进KCs M1极化和KCs源性TNF-α的分泌。而KCs源性TNF-α分泌增加能够经TNFR/caspase 8途径诱导肝星状细胞的凋亡。

| [1] |

Bitto N, Liguori E, la Mura V. Coagulation, microenvironment and liver fibrosis[J]. Cells, 2018, 7(8): 85. DOI:10.3390/cells7080085 |

| [2] |

Yue F, Li WJ, Zou J, et al. Spermidine prolongs lifespan and prevents liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by activating MAP1Smediated autophagy[J]. Cancer Res, 2017, 77(11): 2938-51. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3462 |

| [3] |

Panebianco C, Oben JA, Vinciguerra M, et al. Senescence in hepatic stellate cells as a mechanism of liver fibrosis reversal: a putative synergy between retinoic acid and PPAR-Gamma signalings[J]. Clin Exp Med, 2017, 17(3): 269-80. DOI:10.1007/s10238-016-0438-x |

| [4] |

Liu YW, Chiu YT, Fu SL, et al. Osthole ameliorates hepatic fibrosis and inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation[J]. J Biomed Sci, 2015, 22: 63. DOI:10.1186/s12929-015-0168-5 |

| [5] |

Wang C, Zhang F, Cao Y, et al. Etoposide induces apoptosis in activated human hepatic stellate cells via ER stress[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 34330. DOI:10.1038/srep34330 |

| [6] |

Li YJ, Chen YY, Huang HY, et al. Autophagy mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances the caffeine-induced apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells[J]. Int J Mol Med, 2017, 40(5): 1405-14. DOI:10.3892/ijmm.2017.3145 |

| [7] |

Hernández-Gea V, Hilscher M, Rozenfeld R, et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum stress induces fibrogenic activity in hepatic stellate cells through autophagy[J]. J Hepatol, 2013, 59(1): 98-104. |

| [8] |

Chen Y, Liu ZJ, Liang SY, et al. Role of Kupffer cells in the induction of tolerance of orthotopic liver transplantation in rats[J]. Liver Transpl, 2008, 14(6): 823-36. DOI:10.1002/lt.21450 |

| [9] |

Sica A, Invernizzi P, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in liver homeostasis and pathology[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 59(5): 2034-42. DOI:10.1002/hep.26754 |

| [10] |

Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines[J]. Immunity, 2014, 41(1): 14-20. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008 |

| [11] |

Keestra-Gounder AM, Byndloss MX, Seyffert N, et al. NOD1 and NOD2 signalling links ER stress with inflammation[J]. Nature, 2016, 532(7599): 394-7. DOI:10.1038/nature17631 |

| [12] |

Xu XS, Wang MH, Li JZ, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid alleviates hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury by suppressing the function of Kupffer cells in mice[J]. Biomedecine Pharmacother, 2018, 106: 1271-81. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.046 |

| [13] |

Guo SH, Angela F, Messmer-Blust, et al. Role of A20 in cIAP-2 protection against tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-mediated apoptosis in endothelial cells[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2014, 15(3): 3816-33. DOI:10.3390/ijms15033816 |

| [14] |

HM Ni, Mitchell R, McGill, et al. Caspase inhibition prevents tumor necrosis factor-α-induced apoptosis and promotes necrotic cell death in mouse hepatocytes in vivo and in vitro[J]. Am J Pathol, 2016, 186(10): 2623-36. DOI:10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.06.009 |

| [15] |

Tao Wang, Si-Dong Yang, Sen Liu, et al. 17β-estradiol inhibites tumor necrosis factor-α induced apoptosis of human nucleus pulposus cells via the PI3K/Akt Pathway[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2016, 22(12): 4312-22. |

| [16] |

Abdullahi A, Stanojcic M, Parousis A, et al. Modeling acute ER stress in vivo and in vitro[J]. Shock, 2017, 47(4): 506-13. DOI:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000759 |

| [17] |

Lee YS, Funk LH, Lee JK, et al. Macrophage depletion and Schwann cell transplantation reduce cyst size after rat contusive spinal cord injury[J]. Neural Regen Res, 2018, 13(4): 684-91. DOI:10.4103/1673-5374.230295 |

| [18] |

Martínez-Esparza M, Tristán-Manzano M, Ruiz-Alcaraz AJ, et al. Inflammatory status in human hepatic cirrhosis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(41): 11522-41. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11522 |

| [19] |

GBD Risk Factors Collaborators, Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386(10010): 2287-323. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2 |

| [20] |

Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK. Liver cirrhosis[J]. Lancet, 2014, 383(7): 1749-61. |

| [21] |

Takaaki Higashi, Scott L Friedman, Yujin Hoshida. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2017, 121: 27-42. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.007 |

| [22] |

Guo K, Wang W, Fan W, et al. Arabidopsis GAAP1 and GAAP3 modulate the unfolded protein response and the onset of cell death in response to ER stress[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2018, 9: 348. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2018.00348 |

| [23] |

Matsumoto H, Miyazaki S, Matsuyama S, et al. Selection of autophagy or apoptosis in cells exposed to ER-stress depends on ATF4 expression pattern with or without CHOP expression[J]. Biol Open, 2013, 2(10): 1084-90. DOI:10.1242/bio.20135033 |

| [24] |

Kunito Kawasaki, Ryo Ushioda, Shinya Ito, et al. Deletion of the collagen-specific molecular chaperone Hsp47 causes endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2015, 290(6): 3639-46. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.592139 |

| [25] |

Lim MP, Devi LA, Rozenfeld R. Cannabidiol causes activated hepatic stellate cell death through a mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2011, 2: e170. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2011.52 |

| [26] |

Fujii M, Yoneda A, Takei N, et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum oxidase 1α is critical for collagen secretion from and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase levels in hepatic stellate cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2017, 292(38): 15649-60. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M117.783126 |

| [27] |

Grabinger T, Bode KJ, Demgenski J, et al. Inhibitor of apoptosis protein-1 regulates tumor necrosis factor-mediated destruction of intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152(4): 867-79. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.019 |

| [28] |

Xu H, Li JY, Zhao Y, et al. TNFΑ-induced downregulation of microRNA-186 contributes to apoptosis in rat primary cardiomyocytes[J]. Immunobiol, 2017, 222(5): 778-84. DOI:10.1016/j.imbio.2017.02.005 |

| [29] |

Yuan DT, Huang S, Berger E, et al. Kupffer cell-derived tnf triggers cholangiocellular tumorigenesis through JNK due to chronic mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS[J]. Cancer Cell, 2017, 31(6): 771-89.e6. DOI:10.1016/j.ccell.2017.05.006 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40