脓毒症是重症患者发生死亡的主要原因之一,在2016年脓毒症国际会议上被定义为机体对感染的反应失调导致危及生命的器官功能不全[1-2]。早期评估病情严重程度能有效降低脓毒症患者病死率。当前,有不少指标或评分系统可用于评估脓毒症患者预后[3-6],但能精准评估脓毒症患者预后的则不多,常用的评分系统有序贯器官衰竭评分(SOFA)、简化急性生理评分(SAPS-Ⅱ)、牛津急性疾病严重程度评分(OASIS)、Logistic器官功能障碍系统(LODS)等。有研究显示[7],相较于急性生理学与慢性健康状况评分系统Ⅱ (APACHEⅡ)评分、快速序贯器官衰竭评分(qSOFA)和全身炎症反应综合征(SIRS)评分,SOFA评分预测脓毒症预后效能最强,但受限于样本量不大。近年来,研究者构建出更为简单的OASIS评分,但在评估脓毒症患者预后方面是否强于传统的SAPS-Ⅱ评分、LODS评分,目前尚未得到证实。

MIMIC-Ⅲ(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅲ)数据库[8-9]是在美国国立卫生研究院的资助下,由美国麻省理工学院计算生理学实验室、贝斯以色列迪康医学中心以及飞利浦医疗共同发布的开放的重症医学数据库[10],目前最新版本为MIMIC-Ⅲ v1.4[11],该数据库收集了美国贝斯以色列迪康医学中心重症监护室2001年6月~2012年12月共计4万余真实患者住院信息[12-13]。该数据库样本量大,可靠性高,本研究拟基于MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库比较SOFA、SAPS-Ⅱ、OASIS和LODS评分对脓毒症患者ICU死亡风险的预测价值。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象采用回顾性研究方法,提取MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库中所有脓毒症患者,其中符合要求的有2470例。

1.1.1 纳入标准(1) 鉴于该数据库仅存在出院诊断,要求纳入患者符合国际疾病分类编码(ICD-9)严重脓毒症(编码为99592)或脓毒性休克(编码为78552)诊断标准,且在入ICU±24 h期间已留血培养并已用抗生素治疗且最差SOFA评分≥ 2;(2)年龄≥ 18岁。

1.1.2 排除标准(1) ICU住院时间 < 24 h;(2)多次入ICU患者;(3)心脏术后患者;(4)遗漏关键数据。

1.1.3 伦理学MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库所有患者相关信息均为匿名,无需获得知情同意,且作者已通过Protecting Human Research Participants exam (No. 7849113)并获得该数据库下载及使用权。

1.2 观察指标及分组基于MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库提取脓毒症患者基本信息:年龄,性别,体质量,是否机械通气,收集入ICU 24 h内脓毒症患者首次乳酸水平、白细胞、血红蛋白、血小板、肌酐和尿素氮等实验室检查以及最差SOFA评分、SAPS-Ⅱ评分、OASIS评分和LODS评分。根据ICU存活情况将患者分为存活组和死亡组。

1.3 统计学处理采用PostgreSQL 10.7和Navicat Premium 11.0软件,运用SQL语言(Structure query language)从MIMIC-Ⅲ数据库中提取上述观察指标。采用KolmogorovSmirnov检验各连续变量正态性,呈正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差表示,两组间比较采用独立样本t检验;呈非正态分布的计量资料以中位数和四分位数表示,两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料采用χ2检验进行比较。建立受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线分析比较4种评分系统对脓毒症患者ICU生存情况的预测价值。二项Logistic回归分析4种评分系统对脓毒症患者ICU死亡的影响,单因素分析结果P < 0.1纳入多因素分析。所有研究数据均使用SPSS 24.0软件分析,MedCalc 18.2作图,双侧P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 两组患者基本资料比较(表 1)| 表 1 脓毒症患者基线资料比较 Tab.1 Comparison of baseline characteristics between the survivors and non-survivors with sepsis |

2470例脓毒症患者中ICU内存活1966例,死亡504例。其中存活组中年龄67.8(54.6~80.1)岁,男性1090例,体质量78.6 (66.0~95.0) kg,机械通气865例;死亡组中年龄70.7(59.8~81.7)岁,男性264例,体质量76.3 (62.9~92.2) kg,机械通气374例。死亡组年龄、机械通气占比、乳酸、肌酐、尿素氮、SOFA、SAPS-Ⅱ、OASIS和LODS评分明显高于存活组(均P < 0.05),体质量及血小板明显低于存活组(P < 0.05),而两组间性别、白细胞、血红蛋白之间的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),在各种合并症中,除了死亡组中心律不齐稍低(P=0.045),其余合并症在两组中分布的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

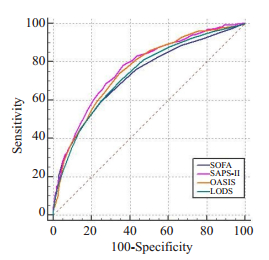

2.2 4种评分系统评估脓毒症患者ICU死亡情况的ROC曲线及曲线下面积比较建立ROC曲线评估4种评分系统对脓毒症患者ICU生存情况的预测,4种评分系统曲线下面积(AUC值)均>0.7,其中SOFA评分AUC值为0.729,95%可信区间(0.711,0.746);SAPS-Ⅱ评分AUC值为0.768,95%可信区间(0.751,0.785),OASIS评分AUC值为0.757,95%可信区间(0.740,0.774),LODS评分AUC值为0.739,95%可信区间(0.721,0.756)(图 1)。选择4种评分系统Youden指数的最大截断点所对应界值作为预测患者死亡的诊断界点,即截断值(cut-off),其中SAPS-Ⅱ评分的敏感度最大,为78.17%,Youden指数也最大,为0.4181,而SOFA评分的特异度最大,为75.13%。将4种评分系统AUC值进行差异性分析(Z检验),得出SAPS-Ⅱ评分AUC值较SOFA评分、LODS评分大,差异有统计学意义(Z=3.679,P < 0.001;Z=3.698,P < 0.001),SAPS-Ⅱ评分AUC值较OASIS大,但差异无统计学意义(Z=1.102,P=0.271);OASIS评分AUC值较LODS评分大,差异有统计学意义(Z=2.172,P=0.030),与SOFA评分AUC值相比,差异无统计学意义(Z=1.709,P=0.088);SOFA评分AUC值最小,与LODS评分相比,差异无统计学意义(Z=1.057,P=0.291,表 2)。

|

图 1 4种评分系统预测脓毒症患者ICU死亡风险的ROC曲线 Fig.1 ROC curves of the 4 scoring systems for predicting ICU mortality in patients with sepsis. |

| 表 2 4种评分系统ROC曲线下比较及差异性分析 Tab.2 Comparison of the AUCs of the 4 scoring systems (Z test) |

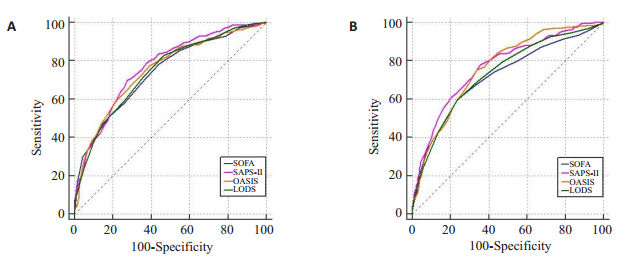

通过入ICU时患者是否合并脓毒性休克分为A、B两组(A组:不合并脓毒性休克,B组:合并脓毒性休克)。在A组患者中,SOFA评分、SAPS-Ⅱ评分、OASIS评分、LODS评分预测ICU死亡的AUC值分别为0.741 (0.714-0.766)、0.769 (0.743-0.793)、0.752 (0.726-0.777)、0.745(0.719-0.770),其中SAPS-Ⅱ评分AUC值最大。在B组患者中,SOFA评分、SAPS-Ⅱ评分、OASIS评分、LODS评分预测ICU死亡的AUC值分别为0.719 (0.693-0.743)、0.768 (0.745-0.791)、0.762 (0.738-0.785)、0.734 (0.709-0.758),其中SAPS-Ⅱ评分与OASIS评分AUC值明显较SOFA评分和LODS评分大(图 2)。

|

图 2 4种评分系统预测是否合并脓毒性休克患者ICU死亡风险的ROC曲线 Fig.2 ROC curves of four scoring systems for predicting ICU mortality in patients with orwithoutsepticshock. A: Withoutsepticshock; B: Withsepticshock; SOFA: Sequential organ failure assessment; SAPS-Ⅱ: Simplified Acute Physiology Score Ⅱ; OASIS: Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score; LODS: Logistic Organ Dysfunction System; SE: Standard error; ROC: Receiver operator characteristic curve; CI: Confidence interval. |

校正前4种评分系统均是脓毒症患者ICU死亡的危险因素(均P < 0.001),将单因素回归有统计学意义的指标(年龄,机械通气,乳酸,肌酐,尿素氮,心律不齐以及SOFA、SAPS-Ⅱ、OASIS、LODS评分)纳入多因素归方程,发现有机械通气、高乳酸、低肌酐、高尿素氮均是ICU患者发生死亡的独立危险因素;在4种评分中,SOFA、SAPS-Ⅱ、OASIS评分系统均是脓毒症患者ICU死亡的独立危险因素(OR:1.08,95%CI:1.03-1.14,P= 0.001;OR:1.04,95%CI:1.02-1.05,P < 0.001;OR:1.04,95%CI:1.01-1.06,P=0.001),但LODS评分与脓毒症患者发生ICU死亡无明显关系(OR:0.96,95%CI:0.89-1.04,P=0.350,表 3)。

| 表 3 4种评分系统对所有脓毒症患者ICU死亡风险的二项Logistic回归分析 Tab.3 Binomial logistic regression analysis of the 4 scoring systems for ICU mortality in patients with sepsis |

在ICU患者中,脓毒症发病率高,死亡率亦高达10%,若进一步发展成为脓毒性休克,则死亡率上升至40%[1],近几年早期评估脓毒症患者病情严重程度及预测患者预后已成为重症医学的研究热点[14-17]。

SOFA评分于2016年被列为脓毒症(sepsis 3.0)诊断标准,作为目前临床最常用的重症评分系统,在多项大型回顾性研究中已被证明能有效评估脓毒症患者预后[18-20]。SAPS-Ⅱ评分最初由Jean-Roger等[21]提出,是目前临床上较常用的疾病严重程度评分系统,有研究证实,在预测脓毒症患者ICU死亡及住院死亡情况时可能优于SOFA评分[22]。OASIS评分是由Johnson等[23]在2013年通过机器学习算法对APACHEⅡ的参数进行分析构建得出,其包含了10项容易获得的基础参数(转入ICU前的住院时间、年龄、格拉斯哥昏迷评分、心率、平均动脉压、呼吸频率、体温、入ICU第一个24 h内的尿量、有无机械通气以及是否手术),多项研究表明其与重症患者预后相关[24-25]。在预测ICU患者短期预后中,OASIS评分与SAPS Ⅱ评分对成年ICU患者短期预后的预测价值相比无显著差异[26],Chen等[22]发现在脓毒症患者中,OASIS评分与SOFA评分对患者ICU死亡及住院死亡的差异亦无统计学意义。本研究则发现,在预测脓毒症患者ICU死亡情况中SOFA评分特异度最高,为75.13%,但敏感度最低,为59.13%,AUC值较SAPS-Ⅱ评分及OASIS评分显著偏低,且在预测脓毒性休克患者发生死亡风险的能力明显低于预测单纯脓毒症患者(AUC值分别为0.719和0.741),这提示SOFA评分对脓毒症死亡风险评估能力不及SAPS-Ⅱ评分及OASIS评分。

LODS评分纳入的每个变量都是经过Logistic回归筛选与计算权重,该系统得出的总分数与病情严重程度密切相关[27-28],有研究发现在预测脓毒症患者预后情况时,LODS评分与SOFA评分的差异无统计学意义[29],但在评估病情更为严重的脓毒性休克患者预后时,LODS评分可能具有更好的预测价值[30]。本研究则发现,LODS评分评估脓毒性休克患者死亡风险的能力并不强于单纯脓毒症(AUC值分别为0.734和0.745),而且在二项Logistic回归多因素分析后,发现LODS评分并不能影响脓毒症患者ICU死亡(OR:0.96,95%CI:0.89-1.04,P=0.350)。

本研究有一定的局限性,首先该研究纳入脓毒症患者均来源于美国贝斯以色列迪康医学中心重症监护室,属于单中心回顾性研究,主要对象为白色人种,其研究结果可能存在种族差异性,且该数据库收集2001~2012年重症监护室的患者相关信息,而脓毒症诊断与治疗在这段时期内变化明显。其次,在不同感染部位所致脓毒症患者中,各评分系统对预后的判断亦存在差异[31],而本研究未能区分不同感染部位所致脓毒症患者。最后,我们未能分析各项评分系统的动态改变,而评分系统的动态改变更能直接反映脓毒症患者的预后。

综上所述,SOFA、SAPS-Ⅱ和OASIS评分均能预测脓毒症患者ICU死亡风险,但SAPS-Ⅱ评分和OASIS评分预测价值优于SOFA评分及LODS评分。

| [1] |

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-10. |

| [2] |

Reinhart K, Daniels R, Kissoon N, et al. Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority - A WHO resolution[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(5): 414-7. |

| [3] |

Serafim R, Gomes JA, Salluh J, et al. A comparison of the QuickSOFA and systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria for the diagnosis of sepsis and prediction of mortality: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis[J]. Chest, 2018, 153(3): 646-55. |

| [4] |

Djordjevic D, Rondovic G, Surbatovic M, et al. Neutrophil-toLymphocyte ratio, Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte ratio, Platelet-toLymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet Volume-to-Platelet count ratio as biomarkers in critically ill and injured patients: which ratio to choose to predict outcome and Nature of bacteremia?[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2018, 3758068. |

| [5] |

Khwannimit B, Bhurayanontachai R, Vattanavanit V. Comparison of the performance of SOFA, qSOFA and SIRS for predicting mortality and organ failure among sepsis patients admitted to the intensive care unit in a middle-income country[J]. J Crit Care, 2018, 44: 156-60. |

| [6] |

Finkelsztein EJ, Jones DS, Ma KC, et al. Comparison of qSOFA and SIRS for predicting adverse outcomes of patients with suspicion of sepsis outside the intensive care unit[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 73. |

| [7] |

王盛标, 李涛, 李云峰, 等. 4种评分系统对脓毒症患者预后的评估价值:附311例回顾性分析[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2017, 29(2): 133-8. |

| [8] |

柳青青, 田国祥, 宋伟伦, 等. MIMIC代码库的简要介绍[J]. 中国循证心血管医学杂志, 2018, 10(11): 1289-92. |

| [9] |

范勇, 赵宇卓, 李沛尧, 等. 危急重症监护数据库MIMIC-Ⅲ疾病谱分析[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2018, 30(6): P531-7. |

| [10] |

Saeed M, Villarroel M, Reisner AT, et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care Ⅱ: A public-access intensive care unit database[J]. Crit Care Med, 2011, 39(5): 952-60. |

| [11] |

Zhang Z. Accessing critical care big data: a step by step approach[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2015, 7(3): 238-42. |

| [12] |

Johnson AE, Pollard TJ, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-Ⅲ, a freely accessible critical care database[J]. Sci Data, 2016, 3: 160035. |

| [13] |

Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Glass L, et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals[J]. Circulation, 2000, 101(23): E215-20. |

| [14] |

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(3): 486-552. |

| [15] |

Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, et al. Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2017, 195(7): 906-11. |

| [16] |

Tacke F, Roderburg C, Benz F, et al. Levels of circulating miR-133a are elevated in sepsis and predict mortality in critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care Med, 2014, 42(5): 1096-104. |

| [17] |

Gao M, Zhang L, Liu Y, et al. Use of blood urea Nitrogen, creatinine, interleukin-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor in combination to predict the severity and outcome of abdominal sepsis in rats[J]. Inflamm Res, 2012, 61(8): 889-97. |

| [18] |

Raith EP, Udy AA, Bailey M, et al. Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for In-Hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit[J]. JAMA, 2017, 317(3): 290-300. |

| [19] |

de Grooth HJ, Geenen IL, Girbes AR, et al. SOFA and mortality endpoints in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 38. |

| [20] |

Liu Z, Meng Z, Li Y, et al. Prognostic accuracy of the serum lactate level, the SOFA score and the qSOFA score for mortality among adults with Sepsis[J]. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2019, 27(1): 51. |

| [21] |

Jean-Roger LG. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS Ⅱ) based on a European/North American multicenter study[J]. JAMA, 1993, 270(24): 2957. |

| [22] |

Chen Q, Zhang L, Ge S, et al. Prognosis predictive value of the Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score for sepsis: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Peer J, 2019, 7: e7083. |

| [23] |

Johnson AE, Kramer AA, Clifford GD. A new severity of illness scale using a subset of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation data elements shows comparable predictive accuracy[J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41(7): 1711-8. |

| [24] |

陈钦桂, 谢锐杰, 陈燕珠, 等. 牛津急性疾病严重程度评分鉴别快速序贯器官功能衰竭评分阴性脓毒症患者的临床价值[J]. 中华结核和呼吸杂志, 2018, 41(9): 701-8. |

| [25] |

张牧城, 汪正光, 洪曦菲, 等. 牛津急性疾病严重程度评分对重症患者病情评估的价值:单中心470例病例分析[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2017, 26(2): 197-201. |

| [26] |

陈钦桂, 何婉媚, 郑海崇, 等. 简化急性生理评分Ⅱ与牛津急性疾病严重程度评分对重症监护病房患者短期预后的预测价值比较[J]. 中华重症医学电子杂志:网络版, 2018, 4(2): P159-63. |

| [27] |

Gall JL. The logistic organ dysfunction system. a new way to assess organ dysfunction in the intensive care unit. ICU scoring group[J]. JAMA, 1996, 276(10): 802-10. |

| [28] |

Lamia B, Hellot MF, Girault C, et al. Changes in severity and organ failure scores as prognostic factors in onco-hematological malignancy patients admitted to the ICU[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2006, 32(10): 1560-8. |

| [29] |

Wang H, Ye L, Yu L, et al. Performance of sequential organ failure assessment, logistic organ dysfunction and multiple organ dysfunction score in severe sepsis within Chinese intensive care units[J]. Anaesth Intensive Care, 2011, 39(1): 55-60. |

| [30] |

黄金桔, 陈钦昌, 林转娣. Logistic器官功能障碍评分系统与序贯器官衰竭评估评分对脓毒性休克预后预测价值的比较[J]. 中国急救医学, 2019, 39(4): 360-5. |

| [31] |

汪颖, 王迪芬, 付江泉, 等. SOFA、qSOFA评分和传统指标对脓毒症预后的判断价值[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2017, 29(8): 700-4. |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40