Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is the most sensitive and widely used technique for early diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke[1]. A lesion showing a hyperintense signal on DWI indicates ischemic stroke, which occurs within minutes and remains hyperintense in the first few weeks after stoke. Hyperintense signals on DWI with decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values are usually considered to indicate an irreversible ischemic damage and the infarct core of a cerebral infarction[2]. However, several studies have demonstrated the reversibility of DWI hyperintense signals in the anterior and posterior circulations in stroke patients[3]; but these studies examined only small embolic lesions, and the reversibility of extensive brain lesions following ischemic stroke remain poorly documented.

The efficacy of intra-arterial thrombectomy for large vessel occlusions has been confirmed by large-scale randomized clinical trials[4-5], but patients with large pretreatment DWI lesions were excluded from these trials. The outcome of large DWI volume (>70 mL) after endovascular treatment was rarely evaluated. The results were controversial, with low rates of good prognosis ranging from 0% to 17% and favorable outcome in every third patients after successful endovascular reperfusion[6]. Herein we report a case of middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion with large DWI lesion, which was obviously reversed after successful recanalization with thrombectomy.

CASE PRESENTATION Patient history and managementA 63-year-old Chinese male patient was transferred to our stroke center with a decreased level of consciousness. About 6.8 h previously, he complained of sudden onset of dysarthria and slight weakness on the left side. He was taken to a local hospital and cranial computed tomography (CT) showed no significant abnormality. Acute ischemia stroke was highly suspected and he was given antiplatelet therapy. His symptoms aggravated rapidly with a decreased level of consciousness before transferring to our Emergency Department (ED).

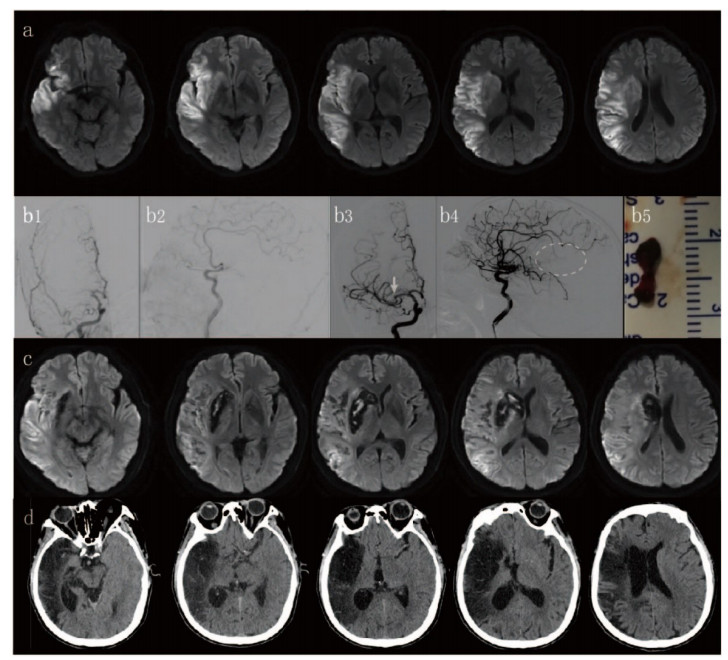

In the ED, physical examination showed that the patient had obvious confusion with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 9 (E2V3M4), presenting also with gaze deviation toward the right side, left drooping face, and left side weakness with muscle strength of 0/6. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed at 7.5 h following the symptom onset. MR angiography (MRA) suggested proximal occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and the volume of infarction on DWI was 91.5 mL calculated using a semi-quantitative software (GE post processing workstation; Fig. 1a).

|

Fig.1 Cranial MRI, DSA and CT images of the patient. MRI revealed large infarctions in the right temporal, frontal and parietal lobes (a). Initial angiography revealed proximal occlusions of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA; b1-b2). Successful recanalization was achieved after the procedure with a retrieved thrombosis of 3×10 mm (b3-b5), but the superior trunk of the right MCA remained occluded (b3) with few blood vessels seen in the oval region (b4). One week after the procedure, MRI revealed significantly decreased DWI hyperintensity and local hemorrhage was observed in the right putamen and the head of the caudate nucleus (c). During the follow-up, CT confirmed old infarctions of the MCA territory (d). |

With informed consent by his family members, the patient was transferred for thrombectomy with a stent retriever (Solitaire-FR 6 × 30 mm, Irvine, CA, USA). Recanalization and thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) grade 3 was achieved 8.5 h after the symptom onset (Fig. 1b). After the procedure, the symptoms of the patient improved significantly. He was awake 24 h after the procedure and capable of clear speech with left side muscle strength of level 5. The patient reported risk factors for cerebrovascular diseases including heavy smoking and drinking but had no other risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiac source of embolism, atrial fibrillation, thrombophilia or vasculitis.

MRI and MRA performed 1 week after the procedure confirmed the reperfusion of the brain and showed a significantly decreased infarct volume to 11.58 mL on DWI and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (Fig. 1c).

The patient was discharged with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 1 and advised to regularly take anti-platelet medicine and quit smoking and drinking. During the two-year follow-up, the patient was fully independent and cranial CT revealed old infarctions in the right frontal-temporalparietal lobes (Fig. 1d).

MRI assessmentAll the MR images were acquired using a 3.0 Tesla scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The area of the baseline and follow-up DWI was delineated manually and calculated by automated software (GE post processing workstation). The volume of the DWI hyperintensity was 91.56 mL at baseline and 11.58 mL after the procedure, suggesting that a DWI hyperintensity volume of 79.98 mL had been reversed.

DISCUSSIONIschemic stroke with an extensive infract size in the hemisphere may cause space-occupying cerebral edema, which leads to rapid deterioration of the neurological status. In the most severe cases, malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction involves the whole territory of MCA, and this catastrophic condition could result in a high mortality of up to 80% if treated conservatively[7-9]. The main clinical features of malignant MCA infarction include most commonly hemiparesis and gaze deviation, followed by intracranial hypertension with headache, vomiting, papilledema and reduced consciousness.

Previous studies have demonstrated that intra-arterial thrombectomy is beneficial for patients with large vessel occlusions[10]. These studies, however, failed to address the issue in the context of large DWI lesion volumes. In the Diffusion Weighted Imaging Evaluation for Understanding Stroke Evolution Study-2 (DEFUSE-2) and Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits-Intra-Arterial (EXTEND-IA) studies, DWI lesion volumes >70 mL, as compared with DWI lesion volumes >50 mL in SWIFT PRIME trial, was listed as an exclusion criterion for intra-arterial thrombectomy[11]. Gilgen et al tested the benefit of endovascular treatment in 105 patients with a DWI lesion volume >70 mL, and found that favorable outcomes were achieved in 35.5% of the patients (modified Rankin scale score of 0-2) after TICI 2b-3 reperfusion[6]. Based on this encouraging finding and severe clinical manifestations of the patient, we chose emergency thrombectomy to rescue the patient.

Hyperintense DWI lesions are considered to represent the irreversibly damaged ischemic core. But recent studies have suggested a high rate of DWI lesion reversal in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic stroke (TIA) and also in stroke patients following thrombolytic therapy[1]. Kidwell et al[12] reported 7 patients with large artery anterior circulation occlusions at angiography, and vessel recanalization was achieved and the mean DWI lesion volume decreased from 23 cm3 at baseline to 10 cm3 after thrombolysis with combined treatment with intravenous/intra-arterial tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). DWI reversibility was also observed in posterior circulation and pediatric ischemic stroke secondary to moyamoya disease[3].

It is widely accepted that DWI lesion reversibility is consistent with neurological improvement[13]. An extensive area of DWI hyperintensities and CT hypointensities do not necessarily indicate irreversible cerebral damage[14]. In our case, the patient's NIHSS score decreased significantly after successful recanalization, but follow-up cranial CT showed large lesions similar with the DWI findings before the procedure rather than those after the procedure. A possible explanation lies in the relatively low resolution of CT, which may cause an overestimation of the lesions and hence the mismatch between CT findings and the clinical manifestations.

Our case highlights the possibility of DWI lesion reversibility, consistent with the findings in previous studies. A large DWI lesion volume of 79.98 mL was reversed following delayed recanalization up to 8.5 h after the symptom onset, suggesting the need of re-evaluation of the meaning of DWI hyperintensity- which can be salvageable by recanalization. In addition, the cut-off volume for endovascular thrombectomy for acute stroke needs further validation by future randomized controlled trials to benefit more patients with large baseline DWI lesions.

| [1] |

Albach FN, Brunecker P, Usnich T, et al. Complete early reversal of diffusion-weighted imaging hyperintensities after ischemic stroke is mainly limited to small embolic lesions[J]. Stroke, 2013, 44(4): 1043-8. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.676346 |

| [2] |

Kranz PG, Eastwood JD. Does diffusion-weighted imaging represent the ischemic core? An evidence-based systematic review[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2009, 30(6): 1206-12. DOI:10.3174/ajnr.A1547 |

| [3] |

Tortora F, Cirillo M, Ferrara M, et al. DWI reversibility after intra-arterial thrombolysis. A case report and literature review[J]. Neuroradiol J, 2010, 23(6): 752-62. DOI:10.1177/197140091002300618 |

| [4] |

Fransen PS, Beumer D, Berkhemer OA, et al. MR CLEAN, a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands:study protocol for a randomized controlled trial[J]. Trials, 2014, 15: 343. DOI:10.1186/1745-6215-15-343 |

| [5] |

Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(24): 2296-306. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 |

| [6] |

Gilgen MD, Klimek D, Liesirova KT, et al. Younger stroke patients with large pretreatment diffusion-weighted imaging lesions may benefit from endovascular treatment[J]. Stroke, 2015, 46(9): 2510-6. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010250 |

| [7] |

Heiss WD. Malignant MCA infarction:pathophysiology and imaging for early diagnosis and management decisions[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2016, 41(1-2): 1-7. |

| [8] |

Nitta N, Nozaki K. Treatment for large cerebral infarction:past, present, and future[J]. World Neurosurg, 2015, 83(4): 483-5. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2014.08.054 |

| [9] |

Torbey MT, Bosel J, Rhoney DH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of large hemispheric infarction:a statement for health care professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the German Society for Neuro-intensive Care and Emergency Medicine[J]. Neurocrit Care, 2015, 22(1): 146-64. |

| [10] |

Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke:a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10029): 1723-31. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X |

| [11] |

Lansberg MG, Straka M, Kemp S, et al. MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2):a prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2012, 11(10): 860-7. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70203-X |

| [12] |

Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Mattiello J, et al. Thrombolytic reversal of acute human cerebral ischemic injury shown by diffusion/perfusion magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Ann Neurol, 2000, 47(4): 462-9. DOI:10.1002/1531-8249(200004)47:4<462::AID-ANA9>3.0.CO;2-Y |

| [13] |

Soize S, Tisserand M, Charron S, et al. How sustained is 24-hour diffusion-weighted imaging lesion reversal[J]. Stroke, 2015, 46(3): 704-10. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008322 |

| [14] |

Tamura G, Ihara S, Morota N. Reversible diffusion weighted imaging hyperintensities during the acute phase of ischemic stroke in pediatric moyamoya disease:a case report[J]. Childs Nerv Syst, 2016, 32(8): 1531-5. DOI:10.1007/s00381-016-3052-z |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40