2. 蚌埠医学院第二附属医院检验科,安徽 蚌埠 233040

2. Department of Clinical Laboratory, Second Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College, Bengbu 233040, China

急性肺损伤(ALI)是由于多种因素导致肺组织结构改变而引起的急性进行性呼吸衰竭,ALI严重时可进一步发展为急性呼吸窘迫综合征。ALI是临床常见危重症,死亡率高达30%~40%,其发病率与死亡率随年龄而增加[1-2]。

肺泡巨噬细胞(AM)是聚居在肺部气道和肺泡腔的一线防御细胞。作为专职吞噬细胞,AM通过吞噬作用识别和清除气道内随呼吸进入的病原体和颗粒物[3]。吞噬作用是细胞摄取直径大于0.5 μm颗粒的过程,主要由树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、中性粒细胞等专职吞噬细胞执行。AM通过模式识别受体、补体受体及Fcγ受体等有效清除病原颗粒和凋亡细胞从而在机体抵御病原微生物感染和维持机体内环境平衡稳定过程中起重要作用[4]。AM的吞噬功能易受外界环境因素和疾病状态的影响[5]。如香烟烟雾降低了补体介导的AM对肺炎链球菌的吞噬作用[6],而高糖和酒精因素均可降低AM的吞噬作用[7-8]。研究表明衰老可明显降低AM的吞噬作用[9-10]。研究发现慢性阻塞性肺病患者AM(而非血中巨噬细胞)吞噬流感嗜血杆菌功能受损[11]。有学者证明难治性哮喘病人AM吞噬葡萄球菌功能降低[12]。但目前关于ALI中AM吞噬功能是否有变化,还不甚清楚。

本研究通过流式细胞术和荧光显微镜观察ALI小鼠AM吞噬功能的变化,并对影响AM吞噬功能变化的因素进行探讨。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要试剂优级胎牛血清购于Wisent;RPMI 1640购于Hyclone;脂多糖购于Sigma;IL-33购于PEPRO TECH;IL-33抗体购于R & D;β-actin抗体,HRP标记的驴抗山羊IgG,HRP标记的羊抗兔IgG,SDS-PAGE凝胶配置试剂盒,胰酶消化液,BCA蛋白浓度测定试剂盒,NP-40裂解液,PMSF,SDS-PAGE蛋白上样缓冲液(5X),PVDF(聚偏二氟乙烯膜),BeyoECL Star(超敏ECL化学发光试剂盒),Hoechst 33342活细胞染色液均购于上海碧云天生物技术有限公司;IL-33 ELISA试剂盒购于CUSABIO;Siglec F和CD11c流式抗体购于Invitrogen;FITC标记荧光微珠购于POLYSCIENCES。

1.2 实验动物及急性肺损伤模型的建立实验动物为昆明种小鼠,购于安徽医科大学实验动物中心。选取体质量25~30 g的昆明种小鼠,随机分为2组:正常对照组和ALI模型组。ALI模型小鼠采用脂多糖(4 mg/kg)经鼻腔1次滴入激发形成,正常对照组使用PBS代替脂多糖鼻滴,造模12 h后处死小鼠,取肺组织进行鉴定与检测。

1.3 小鼠肺组织湿/干比重测定取正常对照组和ALI模型组小鼠肺组织,PBS肺动脉灌洗去除残留血液。肺组织置于吸水纸上吸干表面水分,统一称量左肺质量(湿重)并记录,然后将肺组织放置烘箱24 h后至肺组织质量恒定后取出称质量(干重),计算各组小鼠肺组织湿/干(W/D)比重。

1.4 肺组织HE染色取各组小鼠肺组织,4%多聚甲醛固定24 h,然后使用全自动组织脱水机脱水透明12 h。石蜡包埋,切片机上将石蜡块切成5 μm厚的薄片。切片使用不同浓度的二甲苯进行脱蜡,梯度酒精(高浓度到低浓度)浸泡处理后,苏木素、伊红染色。切片用二甲苯透明后中性树脂封片,显微镜下观察拍照。

1.5 气道上皮细胞的分离与培养小鼠进行支气管插管,使用PBS进行支气管肺泡灌洗,尽可能去除支气管肺泡中白细胞。然后通过肺动脉用PBS灌洗小鼠肺,直至肺部变白。肺组织剪碎后,使用胰酶(0.25%)、DNA酶(100 µg/mL)和胶原酶(40 µg/mL)37 ℃消化30 min。消化液经研磨后分别使用200目和400目滤网各过滤1次。滤液使用含1%FBS的PBS洗涤2次,然后去除红细胞。细胞悬液经洗涤后采用磁珠分选法去除CD45阳性细胞。CD45阴性细胞使用含10%FBS的DMEM重悬后接种6孔板,37 ℃培养2 h。非粘附细胞被收集然后接种预先铺有胶原的6孔板中,37 ℃温箱中培养待用。

1.6 AM的获取与鉴定小鼠处死后固定,气管插管,使用无菌PBS进行支气管肺泡灌洗。支气管肺泡灌洗液(BALF)离心后,沉淀用0.83%NH4Cl裂解红细胞。PBS洗涤细胞后用RPMI 1640完全培养液重悬,接种6孔板,37 ℃培养箱温育2 h,去除悬浮细胞,贴壁细胞就是AM。用0.25%的胰酶消化贴壁的AM,细胞经PBS洗涤2次后用染色缓冲液重悬,PE-Siglec F和PEcy5.5-CD11c荧光抗体4 ℃冰上孵育30 min,PBS洗涤2次后,4%PFA固定,FACS Calibur流式细胞仪检测。

1.7 流式细胞术(FCM)检测AM吞噬功能取各种情况的AM,接种12孔板(5 × 104细胞/孔),每孔加入1 μL FITC标记的荧光微球(含4.55 × 107个直径为1 μm的微球)37 ℃孵育2 h,吸弃培养上清,然后AM用0.25%胰酶消化,再用PBS洗涤3次,4% PFA固定,使用FACS Calibur流式细胞仪检测AM吞噬荧光微球情况。

1.8 荧光显微镜检测肺泡巨噬细胞吞噬功能取正常对照组和ALI组AM,接种12孔板(5 × 104细胞/孔),每孔加入1 μL FITC标记的荧光微球(含4.55 × 107个直径为1 μm的微球)37 ℃孵育2 h,吸弃培养上清,用PBS洗涤细胞3次,然后加入hoechst 33342染色工作液盖住细胞样品,37 ℃孵育10 min,PBS洗涤细胞3次,3 min/次,然后荧光显微镜下观察拍照。

1.9 免疫印迹取小鼠肺组织,匀浆后采用NP-40裂解液提取蛋白,BCA法进行蛋白定量,10%的SDS-PAGE电泳。然后蛋白被转移到PVDF膜上,5%工业脱脂奶粉,室温封闭2 h后,一抗4 ℃孵育过夜。TBST洗膜后HRP标记的二抗孵育2 h,然后使用增强化学发光法曝光显影条带。

1.10 ELISA检测收集BALF的离心上清及各种细胞的培养上清,按照武汉华美(CUSABIO)ELISA试剂盒操作说明书检测上清中IL-33的含量。最后用酶标仪测量各组A450 nm值,制作标准曲线,计算各组IL-33浓度。

1.11 统计学分析实验数据以均数±标准差表示,使用统计软件SPSS16.0进行数据分析,对于多组间比较采用方差分析,两组之间比较用t检验,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

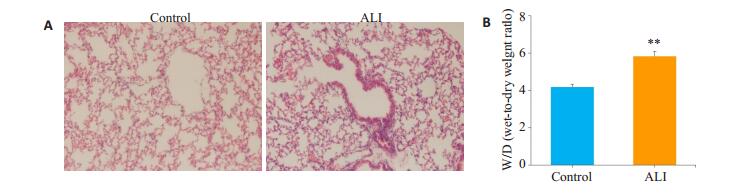

2 结果 2.1 ALI小鼠AM吞噬功能降低本研究中,采用的是脂多糖经气道诱导ALI小鼠模型。脂多糖(4 mg/kg)经鼻腔滴入激发12 h后,小鼠肺泡结构紊乱,肺间质水肿,肺组织炎性细胞浸润明显,肺泡壁增厚(图 1A);与正常对照组相比,ALI模型组小鼠肺湿干重比值明显升高(图 1B)。

|

图 1 ALI模型小鼠构建成功 Fig.1 Successful establishment of the mouse model of ALI. A: HE staining of lung tissue (Original magnification: ×200); B: Wet/dry (W/D) weight ratio of the lung tissue. **P < 0.01 compared to the Control group. |

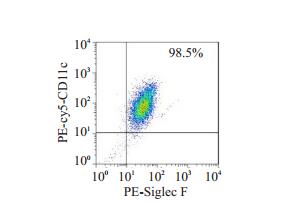

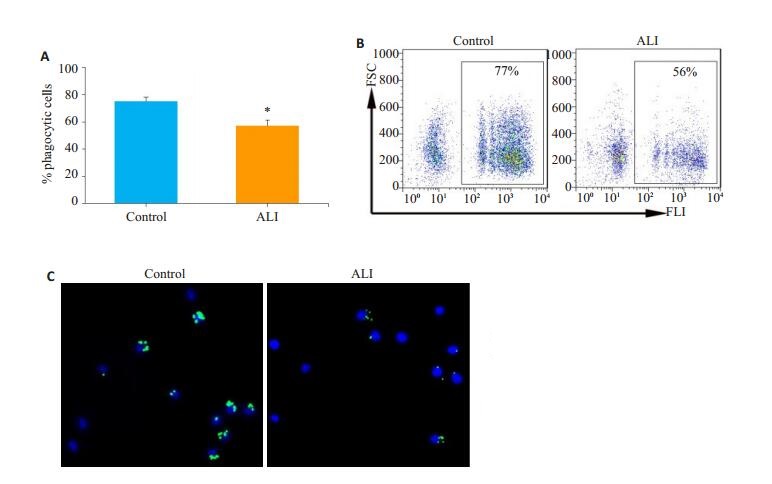

AM是Siglec F+CD11c+表型细胞[13]。采用本研究材料与方法中1.5方法获取的AM,经FCM检测,Siglec F+CD11c+细胞的纯度大于95%(图 2)。取正常对照组和ALI模型小鼠AM,与FITC标记的荧光微球共孵育2 h后,流式细胞术检测AM吞噬荧光微球的情况(图 3),与正常对照组(75.1±3.0)%相比,ALI组AM吞噬荧光微球的比率(57.0±4.3)%明显降低,荧光显微镜的观察显示ALI小鼠AM吞噬功能减弱(图 4)。

|

图 2 分离的AM FCM的鉴定 Fig.2 Identification of isolated alveolar macrophages (AMs) by flow cytometry |

|

图 3 ALI模型小鼠AM吞噬功能降低 Fig.3 AM phagocytosis is weakened in ALI model mice. A: Statistical graph; B: Representative flow cytometry charts. *P < 0.05 compared to the Control group; C: Observation of AM phagocytosis by fluorescence microscope. |

|

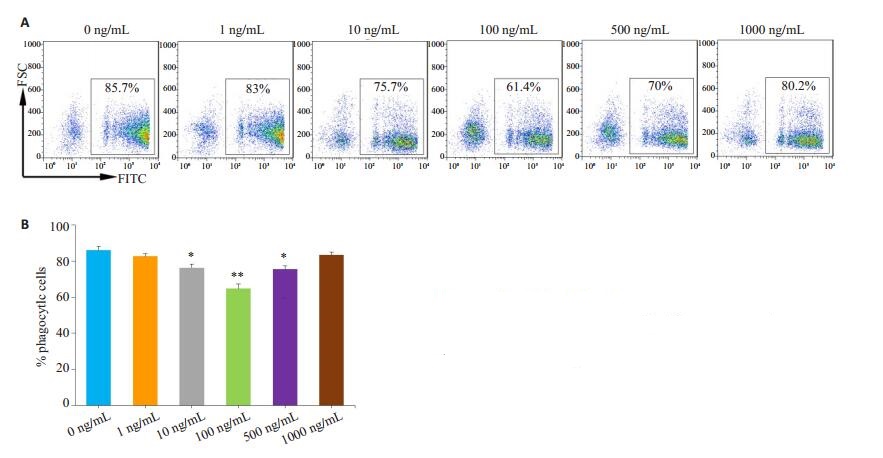

图 4 LPS抑制AM吞噬功能 Fig.4 LPS inhibits phagocytosis of the AMs from normal mice. A: Representative flow cytometry charts; B: Statistical graph; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs 0 ng/mL group. |

首先使用脂多糖直接刺激正常小鼠来源的AM,然后观察其对AM吞噬功能的影响,结果显示10~500 ng/mL的脂多糖抑制AM吞噬荧光微球,其中100 ng/mL浓度的脂多糖抑制功能最强(图 4)。

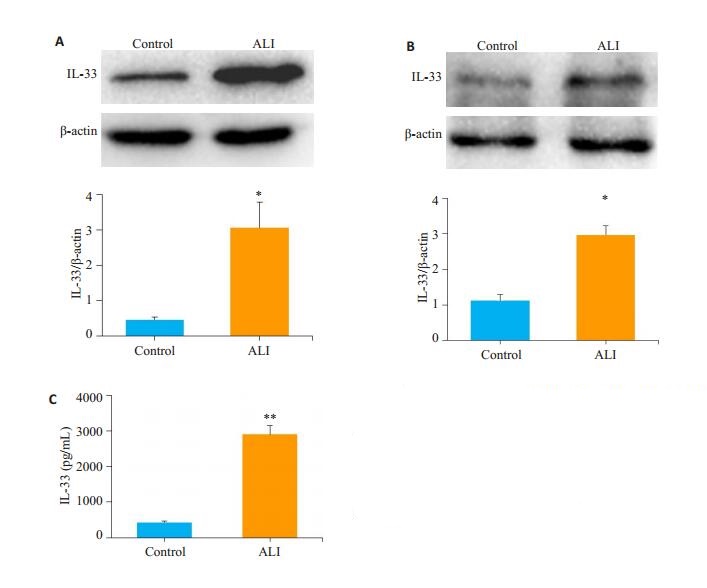

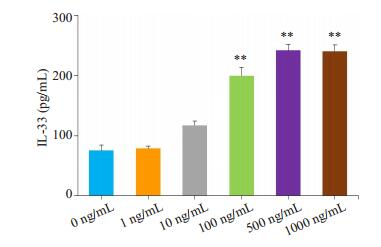

2.3 ALI模型小鼠IL-33产生增加与正常对照小鼠相比,本研究ALI模型小鼠气道上皮细胞、肺组织IL-33的表达和BALF中IL-33的含量均明显增加(图 5);脂多糖(100~1000 ng/mL)刺激肺泡上皮细胞MLE-12,IL-33的分泌明显增加(图 6)。

|

图 5 ALI模型小鼠气道上皮细胞及肺组织IL-33的产生增加 Fig.5 Increased production of IL-33 in lung tissues of ALI model mice (A) and airway epithelial cells (B). A: Representative immunoblots; B: Statistical chart of integrated optical density; C: Increased secretion of IL-33 in BALF of ALI model mice. *P < 0.05 vs the Control group, **P < 0.01 vs Control group. |

|

图 6 LPS刺激肺泡上皮MLE-12细胞IL-33的分泌增加 Fig.6 Increased secretion of IL-33 in BALF of ALI model mice. **P < 0.01 vs 0 ng/mL group. |

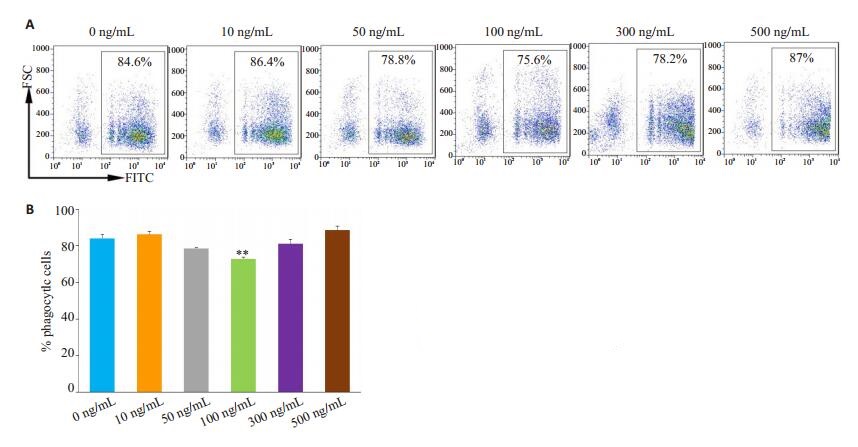

不同浓度IL-33刺激来自于正常小鼠的AM 12 h后,再与FITC标记的微球孵育2 h。流式细胞术检测AM吞噬荧光微球。IL-33(100 ng/mL)抑制AM对荧光微球的吞噬(图 7)。

|

图 7 IL-33抑制AM吞噬功能 Fig.7 IL-33 inhibits phagocytosis of AMs from normal mice. A: Representative flow cytometry charts; B: Statistical graph; **P < 0.01 vs 0 ng/mL group. |

IL-33作为气道上皮细胞损伤后释放的重要预警素,在气道炎症中的作用已为人们所熟知[14]。ALI是临床常见危重病,ALI患者容易发生呼吸道感染,而感染加大了患者进入ARDS阶段的几率[15]。研究表明ALI患者易于金黄色葡萄球菌感染,并且细菌的感染又进一步加重了肺组织炎性损伤[16]。在本研究中,我们证明ALI小鼠AM吞噬功能降低。吞噬作用是古老且保守的过程,是机体抵御病原微生物入侵和促进炎症消退维持机体平衡的重要机制。AM作为专职吞噬细胞,是气道中执行吞噬作用的主要免疫细胞[17]。因此ALI发生时,AM吞噬功能受限,则气道清除病原微生物及凋亡细胞的能力减退,这也可能是ALI患者容易发生呼吸道病原微生物感染和伴随有严重肺部炎症的重要原因。

吞噬作用是一个受到高度调节的免疫学过程,吞噬细胞接触到各种信号刺激后,吞噬功能会发生明显改变[18]。研究表明巨噬细胞受HMGB1刺激后,吞噬功能被抑制,从而导致炎症反应异常消退[19]。PGE2剂量依赖性地减少淀粉样蛋白β诱导的小胶质细胞的吞噬功能[20],而细胞因子IL-1β被报道可诱导中性粒细胞的吞噬功能增强[21]。研究证明IFN-γ的存在或长期暴露于IL-4,削弱了巨噬细胞对凋亡中性粒细胞的清除,但IL-17却增强了巨噬细胞对凋亡细胞的吞噬功能[22]。而我们的研究表明,脂多糖的直接刺激抑制了AM的吞噬功能。Iida的研究显示,脂多糖削弱了小鼠腹腔巨噬细胞的吞噬功能,增加了内内质网应激C/EBP同源蛋白的核内表达[23],这与我们的研究结果相一致。

IL-33是IL-1细胞因子家族成员之一。在哮喘、特应性皮炎、多发性硬化、类风湿性关节炎等多种炎症性疾病状态下,IL-33的表达增加[24-25]。本研究中,ALI模型小鼠(LPS诱导的肺炎)中,IL-33的表达也增加,提示IL-33在ALI中有重要作用。虽然DC等免疫细胞可以产生IL-33,但IL-33多数来源于内皮细胞和上皮细胞,往往作为危险信号(预警素)从受刺激细胞释放出来[26]。与这种观点一致,本研究发现肺泡上皮细胞受脂多糖刺激后,IL-33的产生也增加。IL-33可调控多种适应性免疫细胞,如IL-33可极化Th细胞朝向非典型Th2细胞(产生IL-5、IL-13但无IL-4)。IL-33能独立于TLR的激发诱导效应Th2细胞产生细胞因子[27]。同时IL-33也可影响固有免疫细胞的生物学活性。如IL-33可直接刺激嗜酸性粒细胞产生细胞因子。虽然单独IL-33刺激不能诱导肥大细胞脱颗粒,但可诱导IL-6、TNF-α、MCP-1等细胞因子产生的增加[28-29]。有研究报道,升高的IL-33通过激活STAT3促进了AM MMP2和MMP9的表达[30]。这些结果说明IL-33这一细胞因子可作用于多种靶细胞,而对于同一靶细胞又可产生多种生物学效应。值得注意的是,本研究表明IL-33抑制了AM的吞噬功能。但Tran的研究显示,IL-33的预处理增加了腹腔巨噬细胞对白色念珠菌的吞噬[31],这与我们的研究结论不一致。究其原因,可能是因为AM与腹腔巨噬细胞特性不同,造成了不一样的结果,说明机体内部的复杂性。

综上所述,ALI小鼠AM吞噬能力下降,这可能是由于LPS直接刺激AM引起,或者脂多糖激发肺泡上皮细胞产生的预警素IL-33也可抑制AM吞噬功能。

| [1] |

Horie S, Masterson C, Devaney J, et al. Stem cell therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a promising future?[J]. Curr Opin Crit Care, 2016, 22(1): 14-20. |

| [2] |

Khemani RG, Smith LS, Zimmerman JJ, et al. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, incidence, and epidemiology: proceedings from the pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2015, 16(5 Suppl 1): S23-40. |

| [3] |

Allard B, Panariti A, Martin JG. Alveolar macrophages in the resolution of inflammation, tissue repair, and tolerance to infection[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9(4): 1777. |

| [4] |

Rosales C, Uribe-Querol E. Phagocytosis: a fundamental process in immunity[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2017, 12(7): 9042851. |

| [5] |

Nagre N, Cong X, Pearson AC, et al. Alveolar macrophage phagocytosis and bacteria clearance in mice[J]. J Vis Exp, 2019, 145(2): e59088. |

| [6] |

Phipps JC, Aronoff DM, Curtis JL, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs pulmonary bacterial clearance and alveolar macrophage complement-mediated phagocytosis of streptococcus pneumoniae[J]. Infect Immun, 2010, 78(3): 1214-20. DOI:10.1128/IAI.00963-09 |

| [7] |

Vance J, SantosA, Sadofsky L, et al. Effect of high glucose on human alveolar macrophage phenotype and phagocytosis of mycobacteria[J]. Lung, 2018, 197(1): 89-94. |

| [8] |

Staitieh BS, Egea E, Fan X, et al. Chronic alcohol ingestion impairs rat alveolar macrophage phagocytosis via disruption of RAGE signaling[J]. Am J Med Sci, 2018, 355(5): 497-505. DOI:10.1016/j.amjms.2017.12.013 |

| [9] |

Li Z, Jiao Y, Fan EK, et al. Aging-Impaired filamentous actin polymerization signaling reduces alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria[J]. J Immunol, 2017, 199(9): 3176-86. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1700140 |

| [10] |

Wong CK, Smith CA, Sakamoto K, et al. Aging impairs alveolar macrophage phagocytosis and increases Influenza-Induced mortality in mice[J]. J Immunol, 2017, 199(3): 1060-8. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1700397 |

| [11] |

Berenson CS, Garlipp MA, Grove LJ, et al. Impaired phagocytosis of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by human alveolar macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. J Infect Dis, 2006, 194(10): 1375-84. DOI:10.1086/508428 |

| [12] |

Titze S, Stronegger WJ, Janschitz S, et al. Association of builtenvironment, social-environment and personal factors with bicycling as a mode of transportation among Austrian city dwellers[J]. Prev Med, 2008, 47(3): 252-9. |

| [13] |

Qian F, Deng J, Lee YG, et al. The transcription factor PU.1 promotes alternative macrophage polarization and asthmatic airway inflammation[J]. J Mol Cell Biol, 2015, 7(6): 557-67. DOI:10.1093/jmcb/mjv042 |

| [14] |

Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The airway epithelium in asthma[J]. Nat Med, 2012, 18(5): 684-92. DOI:10.1038/nm.2737 |

| [15] |

Yu H, Ni YN, Liang Z, et al. The effect of aspirin in preventing the acute respiratory distress syndrome/acute lung injury: A metaanalysis[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2018, 36(8): 1486-91. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.017 |

| [16] |

Feng X, Maze M, Koch LG, et al. Exaggerated acute lung injury and impaired antibacterial defenses during staphylococcus aureus infection in rats with the metabolic syndrome[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(5): e0126906. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0126906 |

| [17] |

Li Z, Jiao Y, Fan EK, et al. Aging-Impaired filamentous actin polymerization signaling reduces alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria[J]. J Immunol, 2017, 199(9): 3176-86. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1700140 |

| [18] |

Gordon S. Phagocytosis:an immunobiologic process[J]. Immunity, 2016, 44(3): 463-75. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.026 |

| [19] |

Gj K, Lee HJ, Byun HJ, et al. Novel involvement of miR-522-3p in high-mobility group box 1-induced prostaglandin reductase 1 expression and reduction of phagocytosis[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, 2017, 1864(4): 625-33. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.01.006 |

| [20] |

Nagano T, Kimura SH, Takemura M. Prostaglandin E2 reduces amyloid beta-induced phagocytosis in cultured rat microglia[J]. Brain Res, 2010, 1323(12): 11-7. |

| [21] |

van Dalen S, Blom AB, Walgreen B, et al. IL-1β-mediated activation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells results in PMN reallocation and enhanced phagocytosis: a possible mechanism for the reduction of osteoarthritis pathology[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 27(10): 1075. |

| [22] |

Zizzo G, Cohen PL. IL-17 stimulates differentiation of human antiinflammatory macrophages and phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in response to IL-10 and glucocorticoids[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 190(10): 5237-46. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1203017 |

| [23] |

Iida J, Ishii S, Nakajima Y, et al. Hyperglycaemia augments lipopolysaccharide-induced reduction in rat and human macrophage phagocytosis via the endoplasmic stress-C/EBP homologous protein pathway[J]. Br JAnaesth, 2019, 123(1): 51-9. DOI:10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.040 |

| [24] |

Theoharides TC, Petra AI, Taracanova A, et al. Targeting IL-33 in autoimmunity and inflammation[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2015, 354(1): 24-31. DOI:10.1124/jpet.114.222505 |

| [25] |

Wang H, Wang T, Yuan Z, et al. Role of receptor for advanced glycation end products in regulating lung fluid balance in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury and Infection-Related acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Shock, 2018, 50(4): 472-82. DOI:10.1097/SHK.0000000000001032 |

| [26] |

Milovanovic M, Volarevic V, Radosavljevic G, et al. IL-33/ST2 axis in inflammation and immunopathology[J]. Immunol Res, 2012, 52(1/2, SI): 89-99. |

| [27] |

Mirchandani AS, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Interleukin-33 and the function of innate lymphoid cells[J]. Trends Immunol, 2012, 33(8): 389-96. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2012.04.005 |

| [28] |

Moulin D, Donzé O, Talabot-Ayer D, et al. Interleukin(IL)-33 induces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by mast cells[J]. Cytokine, 2007, 40(3): 216-25. DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2007.09.013 |

| [29] |

Kempuraj D, Twait EC, Williard DE, et al. The novel cytokine interleukin-33 activates acinar cell proinflammatory pathways and induces acute pancreatic inflammation in mice[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e56866. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0056866 |

| [30] |

Liang Y, Yang N, Pan G, et al. Elevated IL-33 promotes expression of MMP2 and MMP9 via activating STAT3 in alveolar macrophages during LPS-induced acute lung injury[J]. Cell Mol Biol Lett, 2018, 31(23): 52. |

| [31] |

Tran VG, Cho HR, Kwon B. IL-33 priming enhances peritoneal macrophage activity in response to candida albicans[J]. Immune Netw, 2014, 14(4): 201-6. DOI:10.4110/in.2014.14.4.201 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40