2. 南方医科大学附属佛山妇幼保健院儿科,广东 佛山 528000

2. Department of Pediatrics, Foshan Women and Children's Hospital Affiliated to Southern Medical University, Foshan 528000, China

造血干细胞移植(HSCT)是治疗重型地中海贫血唯一有效而可靠的方法[1-2]。预处理方案是移植过程中至关重要的环节。预处理的目的是清除宿主固有的造血干细胞,建立起供体造血干细胞耐受的生存环境,以便能顺利造血重建。而预处理强度一直是各移植中心探索的重要问题[3-6]。环联酰胺(Cy)因其抗肿瘤及免疫抑制作用,临床应用普遍。研究表明环联酰胺还具有动员细胞的作用[7-8]。环联酰胺联合粒细胞集落刺激因子在临床上常用作动员骨髓产生更多的造血干细胞,从而收集足够的外周血造血干细胞以备移植[9]。目前大多数移植中心采用白消安(Bu)/ Cy预处理方案[10-13],而本移植中心采用基于Cy/Bu的“NF-08-TM”预处理方案,取得了世界瞩目的成效[14],这一成果是否和Cy动员骨髓造血干细胞(HSCs),从而提高Bu对HSCs清除相关,尚未见相关报道。本研究探索性建立Cy预处理铁过载小鼠模型,检测骨髓造血干细胞的变化,研究Cy对铁过载小鼠骨髓造血干细胞的影响,为进一步阐述Cy前置于Bu的优势提供实验依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 动物C57BL/6纯系小鼠(SPF级)由广东省医学动物实验中心提供以及检测,合格证号SCXK(粤)2013-0002,周龄6~8周,体质量20±2 g。饲养于南方医科大学动物中心SPF级动物房。

1.2 试剂和仪器磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS液),右旋糖酐铁注射液;小鼠血清铁蛋白检测试剂盒;注射用环磷酰胺;BD Mouse Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor CellIsolation Kit(560492),活性氧检测试剂盒(S0033),N-乙酰半胱氨酸(NAC);细胞周期检测试剂盒(CCS012);小鼠骨髓单个核细胞分离试剂盒;全自动五分类细胞计数仪,紫外/可见分光光度计,超高速流式细胞分析仪,多功能酶标仪;

1.3 实验方法 1.3.1 建立铁过载三级危险模型将C57BL/6小鼠40只随机分为4组:对照组(CG)、低剂量铁剂组(LIG)、中剂量铁剂组(MIG)、高剂量铁剂组(HIG)。对照组每次腹腔注射PBS液0.2 mL;低剂量组、中剂量组、高剂量组分别每次腹腔注射右旋糖酐铁0.25、0.5、1 g/kg。丹麦右旋糖酐铁注射液原液浓度为0.1 g/mL,用PBS液稀释到相应的浓度,使每只小鼠每次注射液体为0.2 mL,2次/周,共4周[15-16]。每周称量体质量1~2次并记录。实验结束后1周处死小鼠。采用眼球取血双抗体一步夹心法酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)检测血清铁蛋白(SF)[17];取各组小鼠肝脏、脾脏及股骨。肉眼观察;光镜观察:常规切片,苏木精-伊红染色,400倍镜下观察其病理形态学改变;普鲁士蓝铁染色,油镜下观察骨髓铁的分布情况。

1.3.2 在前期成功实验基础上,取中度危险铁过载模型鼠建立Cy预处理模型设置空白组(CTL),中度危险铁过载模型鼠组(MIG),铁剂+环磷酰胺组(Cy组),其中Cy组又按注射时间不同细分为D1、D2、D3、D4、D5、D6、D7、D14组(处死小鼠当天设为0 d,按注射Cy时间-1、-2、-3、-4、-5、-6、-7、-14 d的不同,设置分组为D1、D2、D3、D4、D5、D6、D7、D14组,对应Cy预处理后第1、2、3、4、5、6、7、14天)。CTL小鼠腹腔注射PBS 0.2 mL每次,MIG小鼠、Cy组小鼠腹腔注射右旋糖酐铁0.5 g/kg,2次/周,共8次,4周后观察1星期,确认模型建立后,CTL、MIG予腹腔注射PBS 0.2 mL每次,Cy组腹腔注射环磷酰胺50 mg/kg×2 d,处死当天设置为0 d,观察Cy注射后第1~7天、14 d外周血象、骨髓单个核细胞(BMMNCs)、造血干细胞(Lin-c-kit+Sca-1+)及细胞周期变化。

1.3.2.1 外周血细胞计数通过摘除眼球取血并用K3EDTA抗凝,用全自动血细胞分析仪检测每组小鼠的白细胞、血小板、血红蛋白和红细胞计数变化

1.3.2.2 BMMNCs分离及计数以颈椎脱臼法处死各组小鼠,用无菌手术刀和镊子依次提取每只小鼠的单侧股骨,剥离干净,剪开股骨两端,用注射器将2%FBS+ Hank's溶液反复抽吸冲出骨髓细胞,吹打成单细胞悬液,加入骨髓单个核细胞分离液取得环状乳白色单个核细胞层,重悬后用全自动血细胞计数仪进行计数。

1.3.2.3 磁珠富集造血干(lin-c-kit+scal+)/祖细胞(lin-ckit+Sca-l-)分选将上述收集到的骨髓单个核细胞悬液,用稀释10倍后的磁珠分离液调整细胞浓度为10~ 20×106/mL。加入表面封闭抗体0.25 μL/106细胞,加入生物素抗体混合物,涡旋后磁珠分离液清洗,弃上清,重悬后放置在磁力架(阴性选择)上8 min,吸出上清备用。

1.3.2.4 造血干细胞(Lin-c-kit+Sca-1+)流式分选将上述富集到的细胞用磁珠分离液清洗,离心后重悬调整至浓度1×109/mL。吸取100 μL上述细胞悬液转移到新的流式管中,按照5×106/细胞加入4 μL抗体依次加入CD34(FITC)、c-kit(PE)、Sca-1(PE-Cy7),Lineage-(APC)加入8 μL,用磁珠分离液清洗,离心弃上清。重悬细胞,浓度调整至1~2×107/mL。管内注入1滴7-ADD混匀。贝克曼超高速流式分选仪计数、分选。

1.3.2.5 流式细胞周期检测收集1×105~1×106HSC,细胞周期分析取上述70%冷乙醇固定的细胞样品,用PBS洗2次,以洗去残留的乙醇,留少许PBS混匀细胞,加入碘化丙啶染液,放入4 ℃冰箱避光30 min,流式细胞仪检测细胞周期的变化。

1.4 统计方法Excel、SPSS18统计软件进行数据统计及作图,结果以均数±标准差来表示,两组之间采用t检验,多组之间采用单因素方差分析进行统计及分析,P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 地中海贫血三级危险铁过载模型建立 2.1.1 小鼠的一般表现与CG相比,低、中、高剂量的铁剂组小鼠在第2周时,耳朵、脚爪、尾巴等部位出现渐深的褐色,皮肤开始脱毛,毛色无光不顺,症状随着时间进行加重。随着实验的进行,铁剂组小鼠活动量减少,目光呆滞,蜷缩成团,竖毛弓背,精神萎靡,反应迟钝,易受惊吓,且高剂量组小鼠死亡4只。

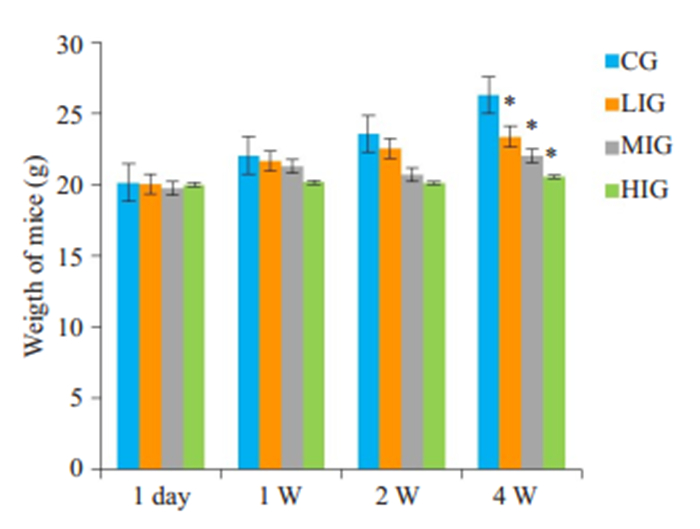

2.1.2 小鼠体质量变化在实验过程不同的时间段,记录各组小鼠体质量变化。第1天,各组小鼠体质量基本无差异,随着时间进展,铁剂组小鼠进食量明显减少,生长缓慢,第4周时,铁剂组小鼠与对照组相比,体质量明显下降,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 1)。

|

图 1 不同剂量的铁剂处理后,各组小鼠体质量随时间的变化情况 Fig.1 Changes of body weight of the mice over time after treatment with iron dextran. CG: Control group; LIG: Low dose iron group; MIG: Middle dose iron group; HIG: High dose iron group. 1 day: The first day of the test; 1W: The first week of the test; 2W: The second week of the test; 4W: The fourth week of the week; Compared with control group, *P < 0.05. |

和CG相比,铁剂组小鼠肝、脾肉眼可见增大、淤血、水肿,上述现象的严重程度和铁剂量的高低呈明显正相关;铁剂组肝脾系数明显增大:LIG、MIG、HIG小鼠肝脏相对质量增加了46.9%、96.5%、160.2%,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.0001)。根据临床经验,人肝脏增加2 cm,对应质量或体积增大50%,则可认为低剂量组肝脏肿大<2.5 cm,而高剂量组肝肿大>5 cm,中剂量组肝脏肿大程度在二者之间;和对照组相比,低、中、高剂量组脾脏指数分别升高了24%、97.6%、155.8%,差异具有显著性统计学意义(P < 0.05,表 1)。

| 表 1 给不同剂量的铁剂处理后,各小组肝脾系数检测结果 Tab.1 Liver and spleen coefficients of the mice in each group after treatment with iron dextran |

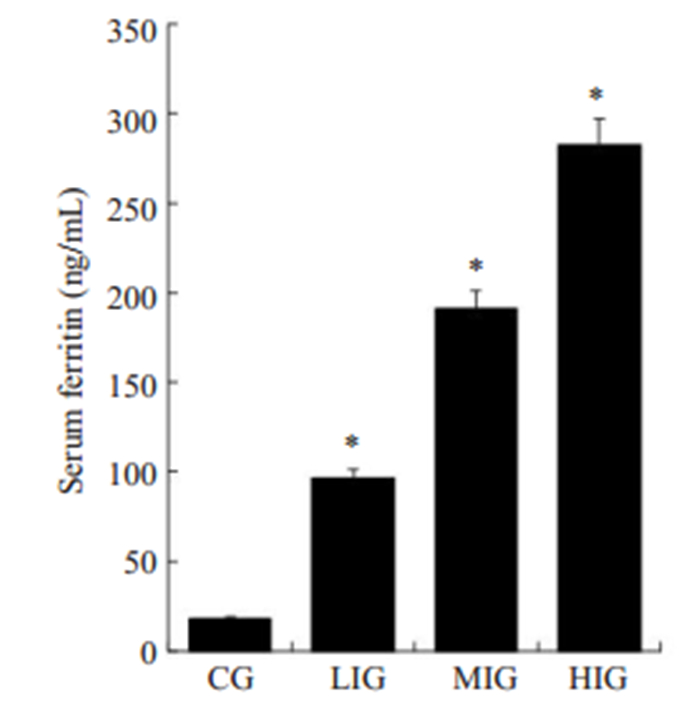

经酶联免疫吸附试验所得血清铁蛋白值,LIG、MIG、HIG组铁蛋白分别为对照组的5.2倍、10.4倍、15.3倍,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 2)。

|

图 2 不同剂量的铁剂处理后,各组小鼠血清铁蛋白检测结果 Fig.2 Detection of serum ferritin of the mice in each group by ELISA after the treatments. CG: Control group; LIG: Low dose iron group; MIG:Middle dose iron group; HIG: High dose iron group; Compared with control group, *P < 0.05. |

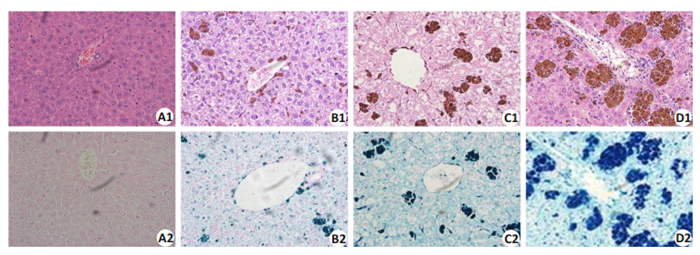

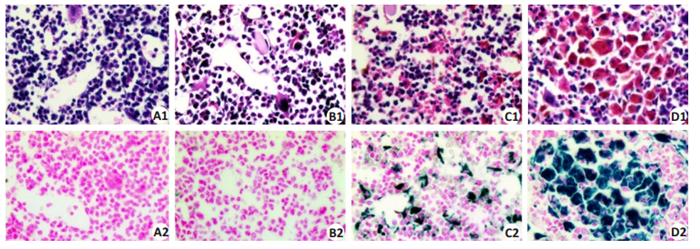

CG组小鼠肝脏未见明显病理改变,光镜下细胞排列整齐、形态规则,光镜下HE、普鲁士染色正常(图 3A1,A2);LIG组小鼠肝脏内可见轻度增大、水肿、淤血,光镜下肝细胞内可见团块状铁褐色沉积,未见明显坏死、炎性浸润等,普鲁士染色可见少量染成亮蓝色的铁(图 3B1,B2);MIG组可见小鼠肝脏明显肿大、淤血,呈褐色改变,光镜下肝细胞可见凝固性坏色,核固缩、溶解,胞浆内较多铁颗粒存在,普鲁士染色见颗粒状、块状亮蓝色铁沉积(图 3C1,C2);HIG小鼠肝脏重度肿大,整个肝脏相比对照组体积增大2倍左右,水肿、淤血严重,呈深褐色改变,光镜下大片凝固性坏死,细胞内外大片铁颗粒,普鲁士染色可见大片团块状亮蓝色铁(图 3D1,D2)。

|

图 3 不同剂量的铁剂处理后,各组小鼠肝脏HE(上图)及普鲁士染色结果 Fig.3 HE staining and Prussia staining of the lived of the mice in each group (Original magnification: × 400). A1/A2: Control group; B1/B2: Low dose group; C1/C2: Moderate dose group; D1/D2: High dose group. |

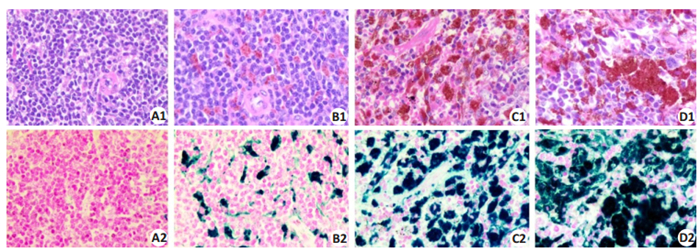

CG组小鼠脾脏未见明显的病理改变,光镜下细胞形态细胞形态正常,排列规则,可见脾小体(图 4A1,A2);LIG组小鼠脾脏肉眼可见体积增大,淤血水肿,呈暗红色,光镜下脾脏边缘区级红髓区可见少量颗粒状褐色沉积,普鲁士染色镜下可见亮蓝色铁颗粒(图 4B1,B2);MIG组肉眼可见明显淤血、肿大,呈褐色改变,光镜下可见脾脏大量铁颗粒沉积,脾小体与红髓区界限不清(图 4C1,C2);HIG组肉眼可见脾脏体积增大明显,淤血、肿大,呈深褐色改变,光镜下脾脏布满大量铁颗粒,脾小体与红髓界限不清(图 4D1,D2)。

|

图 4 不同剂量的铁剂处理后,各组小鼠脾脏HE、普鲁士染色结果 Fig.4 HE staining and Prussia staining of the spleen in each group (×400). A1/A2: Control group; B1/B2: Low dose group; C1/C2: Moderate dose group; D1/D2: High dose group. |

CG组小鼠和LIG组小鼠骨髓光镜下骨髓基质无或有少量浅蓝色铁颗粒和小珠,呈阴性或弱阳性(图 5A1、A2、B1、B2);MIG组骨髓细胞外有较多蓝色铁存在,呈颗粒、小珠、块状(图 5C1、C2);HIG组骨髓细胞内外均有大量黑蓝色铁存在,呈团块状(图 5D1、D2)。

|

图 5 骨髓HE、普鲁士染色结果 Fig.5 HE staining and Prussia staining of the bone marrow of mice in each group (×400). A1/A2: Control group; B1/B2: Low dose group; C1/C2: Moderate dose group; D1/D2: High dose group. |

和MIG小鼠相比,食欲下降明显,行动迟缓,反应迟钝,在第1~2天最明显,第7天及第14天小鼠精神状态及行动较前恢复。

2.2.2 Cy对外周血象的影响和CTL相比,MIG小鼠外周血PLT、YM%、HBC、HGB无明显变化,WBC、YM%升高,差异具有显著性统计学意义(P < 0.05);Cy组和MIG小鼠相比,WBC、YM%在第1天开始下降,第3天降至最低,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),第4天快速回升,第7天基本恢复正常(表 2)

| 表 2 各组小鼠外周血象检测结果 Tab.2 Test results of peripheral blood samples in each group |

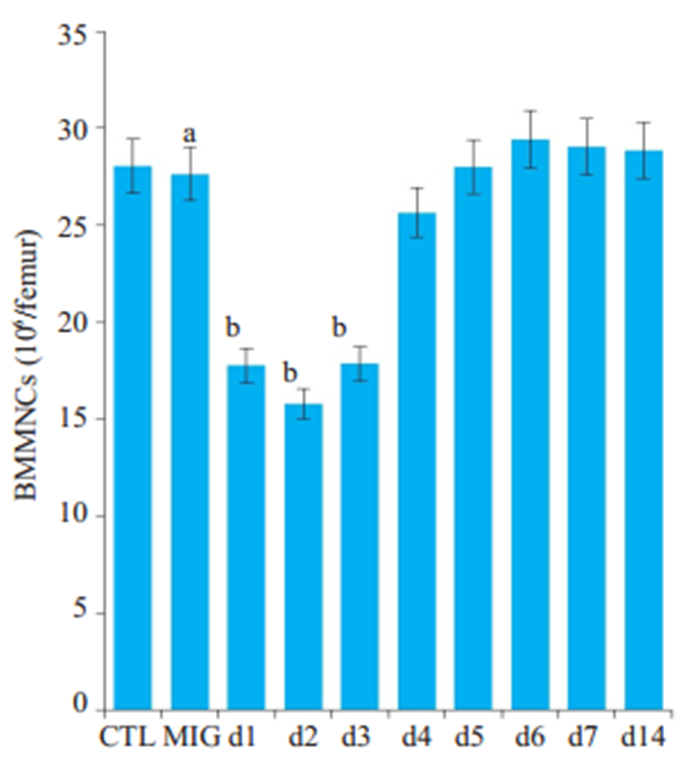

CTL和MIG相比,小鼠股骨BMMNCs数目基本相同,差异不具有统计学意义;Cy组与MIG相比,小鼠股骨BMMNCs数目在第1~ 3天均明显下降,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),第4天开始回升,第5~6天数目基本恢复正常(图 6)。

|

图 6 环磷酰胺作用后,不同组小鼠骨髓单个核细胞变化情况 Fig.6 Canges of bone marrow mononuclear cells after cyclophosphamide treatment. CTL: Control group; MIG: moderate dose iron group; d1-d14: Day 1 to day 14, respectively; Compared with the control group, aP>0.05; Compared with the Middle dose iron group, bP < 0.05. |

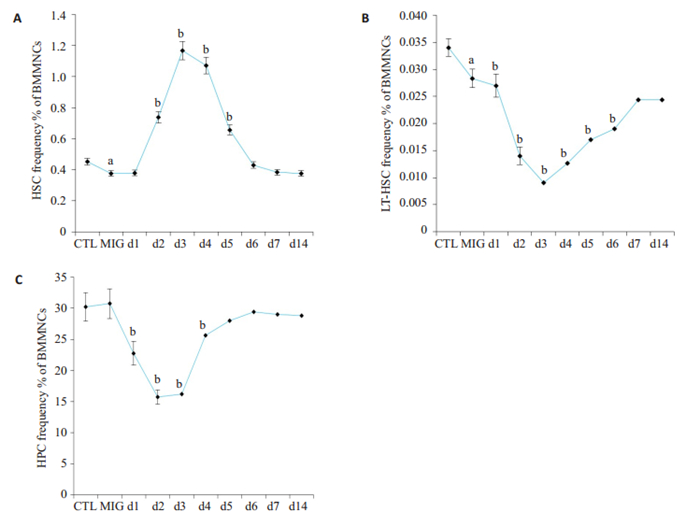

与CTL小鼠相比,MIG小鼠骨髓HPC数目未见明显变化,但HSC以及LT HSC明显降低,提示铁沉积对小鼠远期造血功能产生损害;和MIG小鼠相比,Cy组小鼠的HSCs在D1组开始升高,D3、D4组升至最高,差异具有显著性(P < 0.05),D7组基本恢复正常。而LT-HSC变化与之基本相反(图 7)。

|

图 7 环磷酰胺处理后,小鼠骨髓细胞数目的变化情况 Fig.7 Effect of cyclophosphamide on the number of bone marrow cells. A: Proportion of HSCs; B: Proportion of LTHSCs; C: Proportion of HPCs. CTL: Control group; MIG: Middle dose iron group; d1 to d7: The first day to the seventh day; d14; the fourteenth day; Compared with the control group, aP < 0.05; Compared with the Middle dose iron group, bP < 0.05 |

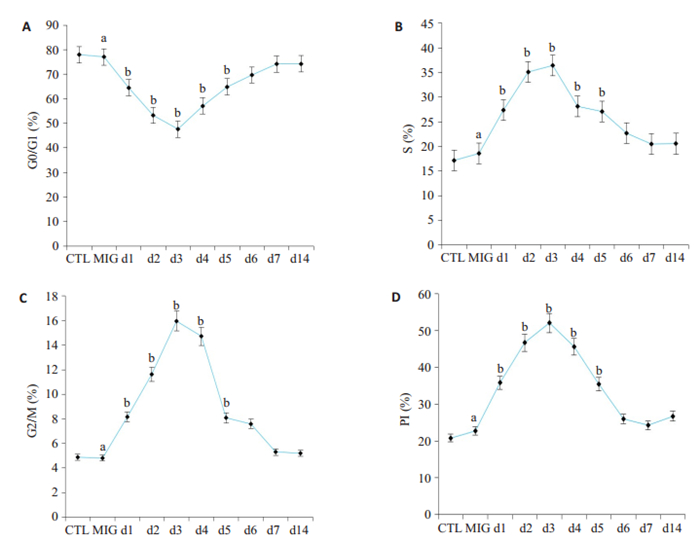

MIG小鼠HSCs细胞周期与CTL小鼠相比,G0/G1、S、G2/M各时期的分布、PI基本相同,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。Cy组小鼠HSCs细胞周期分布和铁过载组小鼠的相比:G0/G1期在第1~2天明显降低,第3天降至最低,第4~5天逐渐回升,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),第6天基本正常。S期、G2/M、PI均在第1~4天明显升高,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),第7天基本恢复正常复正常。静息状态的HSCs进入细胞周期,加速G1期到S期,S期到M期的转化(图 8)。

|

图 8 环磷酰胺处理后,不同组小鼠HSCs细胞周期各时相分布及增殖指数变化 Fig.8 Changes of cell cycle distribution and proliferation index of hematopoietic stem cells after cyclophosphamide treatment. A: Proportion of G0/G1 cell; B: Proportion of S phase cells; C: Proportion of G2/M cells; D: Proliferation index; CTL: Control group; MIG: Middle dose iron group; d1 to d7: The first day to the seventh day; d14; The fourteenth day; Compared with the control group, aP>0.05; Compared with the Middle dose iron group, bP < 0.05. |

地中海贫血是全球最大的单基因遗传性血液病之一。患者长期的输血以及不规律的祛铁导致体内脏器铁过载。目前造血干细胞移植是治疗重型地贫唯一有效可靠的方法。目前造血干细胞移植治疗地贫研究主要集中在移植方式的选择、供者的选择以及预处理方案以及术后的治疗[18-19]。本移植中心不同于其他地贫移植中心,采用前置环磷酰胺于白消安,取得国际领先的移植成绩,本研究旨在探索环磷酰胺对造血干细胞作用特点如何,但是由于临床患者取材所限,可重复性差,很难深入开展研究工作。因此建立Cy预处理铁过载模型有着非常重要的现实意义。

本研究通过给小鼠定期腹腔注射右旋糖酐铁,结合临床对重型β-地贫三级分度标准以及前期的预实验基础,成功模拟建立地贫三级危险模型。Musumeci等[20]通过给小鼠腹腔注射右旋糖酐铁建立铁过载模型,侧重于研究铁沉积引起心脏功能变化。Tsay等[21]建立铁过载模型侧重于研究铁对骨骼及运动的影响。柴笑等[22]研究铁过载侧重于研究铁过载对功能的影响。本研究根据重型β-地中海贫血临床分度标准模拟建立铁过载三级危险模型。小鼠肝脏、脾脏、骨髓中均可见铁不同程度的沉积,且与危险分度成正相关,这与临床患者肝脏、脾脏大量铁沉积是一致的。通过定量、定性对小鼠进行模拟地贫危险级别分级,也符合临床治疗中按照患者处于不同危险分级预处理时给予药物的剂量不同[23-24]。重型高剂量β-地中海贫血为单基因缺陷的遗传性疾病,而我们采用的是基因正常的小鼠,这也是我们建立模型的不足之处。

研究多发性骨髓瘤干细胞动员中发现,Cy联合粒细胞集落刺激因子动员干细胞的数量优于单独使用粒细胞集落刺激因子,并且植入时间相似[25]。研究发现低剂量环磷酰胺如2.5 g/m2动员骨髓瘤干细胞较高剂量环磷酰胺更为安全,与降低环磷酰胺毒性相关[26]。在前期成功建立中度危险铁过载模型基础上,我们进一步研究Cy对铁过载小鼠骨髓细胞作用特点,采用连续两天腹腔注射Cy50 mg/kg[14, 27],检测外周血发现WBC从d1开始下降,d3降至最低,而后逐渐回升,骨髓HSCs变化与外周血WBC变化基本一致,这与Juaristi等[28]建立环磷酰胺单剂量150 mg/kg大鼠模型上观察环磷酰胺对红细胞生成的影响结果外周血象和HSCs恢复特点类似,由此说明此剂量的环磷酰胺对骨髓的毒性作用是暂时的,具有可逆性。HSCs损伤后数目短暂下降后,迅速回升,此时造血干细胞细胞周期状态如何,为此我们继续检测造血干细胞细胞周期分布发现,造血干细胞G0/G1期细胞比例在第1~2天迅速减少,在第3天降至最低,第4天开始回升,而S期细胞、G2-M比例变化以及增殖指数与之相反,说明造血干细胞在此剂量环磷酰胺作用后,出现短暂损伤修复,而后更多静息期HSCs迅速进入细胞周期,并且促进细胞从G1向S期转化,S期向G2期转化,起到动员造血干细胞的作用,且在第4天动员作用最强,此时更多静息状态下的HSCs脱离骨髓龛的保护,进入细胞周期进行增殖,这与利用环磷酰胺200 mg/ kg证明造血干细胞处于不断更新中结果一致[29]。因此若在骨髓细胞动员作用最大时给予具有明显骨髓毒性的Bu, 将明显提高预处理方案对HSCs的清除作用,降低移植排斥风险,提高移植成功率。

综上,本研究在建立铁过载模型的基础上,成功建立了Cy预处理铁过载模型,探讨了Cy在预处理方案中对铁过载小鼠骨髓细胞具有动员作用,且d4动员作用最大,为进一步研究其机制提供了一定的实验基础,对地贫移植预处理方案Cy前置于Bu的优势提供了一定的实验依据。

| [1] |

Park BK, Kim HS, Kim S, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in congenital hemoglobinopathies with myeloablative conditioning and rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin[J]. Blood Res, 2018, 53(2): 145-51. DOI:10.5045/br.2018.53.2.145 |

| [2] |

Crippa S, Rossella V, Aprile A, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells from beta-thalassemia patients have impaired hematopoietic supportive capacity[J]. J Clin Invest, 2019, 129(4): 1566-80. DOI:10.1172/JCI123191 |

| [3] |

Anurathapan U, Pakakasama S, Rujkijyanont P, et al. Pretransplant immunosuppression followed by reduced-toxicity conditioning and stem cell transplantation in high-risk thalassemia: a safe approach to disease control[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2013, 19(8): 1259-62. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.023 |

| [4] |

Anurathapan U, Pakakasama S, Mekjaruskul P, et al. Outcomes of thalassemia patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation by using a standard myeloablative versus a novel reduced-toxicity conditioning regimen according to a new risk stratification[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2014, 20(12): 2066-71. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.07.016 |

| [5] |

Malard F, Milpied N, Blaise D, et al. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor hemopoietic stem cell transplantation in adults with acute myeloid leukemia after reduced-intensity or nonmyeloablative conditioning: a study from the societe francaise de ghreffe de moelle et de therapie cellulaire[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2015, 21(6): 1059-67. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.02.014 |

| [6] |

Liu QF, Fan ZP, Zhang Y, et al. Sequential intensified conditioning and tapering of prophylactic immunosuppressants for graft-versushost disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for refractory leukemia[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2009, 15(11): 1376-85. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.017 |

| [7] |

Winkler IG, Pettit AR, Raggatt LJ, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell mobilizing agents G- CSF, cyclophosphamide or AMD3100 have distinct mechanisms of action on bone marrow HSC niches and bone formation[J]. Leukemia, 2012, 26(7): 1594-601. DOI:10.1038/leu.2012.17 |

| [8] |

Musto P, Simeon V, Grossi A, et al. Predicting poor peripheral blood stem cell collection in patients with multiple myeloma receiving pretransplant induction therapy with novel agents and mobilized with cyclophosphamide plus granulocyte-colony stimulating factor: results from a gruppo italiano malattie EMatologiche dell'Adulto Multiple Myeloma Working Party study[J]. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2015, 17(6): 64. |

| [9] |

Szumilas P, Barcew K, Baskiewicz-Masiuk M, et al. Effect of stem cell mobilization with cyclophosphamide plus granulocyte colonystimulating factor on morphology of haematopoietic organs in mice[J]. Cell Prolif, 2005, 38(1): 47-61. |

| [10] |

Lee J H, Joo Y D, Kim H, et al. Randomized trial of myeloablative conditioning regimens: busulfan plus cyclophosphamide versus busulfan plus fludarabine[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(6): 701-9. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2362 |

| [11] |

Copelan EA, Hamilton BK, Avalos B, et al. Better leukemia-free and overall survival in AML in first remission following cyclophosphamide in combination with busulfan compared with TBI[J]. Blood, 2013, 122(24): 3863-70. DOI:10.1182/blood-2013-07-514448 |

| [12] |

Dhere V, Edelman S, Waller EK, et al. Myeloablative busulfan/ cytoxan conditioning versus reduced-intensity fludarabine/ melphalan conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia[J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 2018, 59(4): 837-43. DOI:10.1080/10428194.2017.1361027 |

| [13] |

Ben-Barouch S, Cohen O, Vidal L, et al. Busulfan fludarabine vs busulfan cyclophosphamide as a preparative regimen before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2016, 51(2): 232-40. DOI:10.1038/bmt.2015.238 |

| [14] |

Li C, Wu X, Feng X, et al. A novel conditioning regimen improves outcomes in beta-thalassemia major patients using unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation[J]. Blood, 2012, 120(19): 3875-81. DOI:10.1182/blood-2012-03-417998 |

| [15] |

Okabe H, Suzuki T, Uehara E, et al. The bone marrow hematopoietic microenvironment is impaired in iron-overloaded mice[J]. Eur J Haematol, 2014, 93(2): 118-28. DOI:10.1111/ejh.12309 |

| [16] |

Musumeci M, Maccari S, Sestili P, et al. The C57BL/6 genetic background confers cardioprotection in iron- overloaded mice[J]. Blood Transfus, 2013, 11(1): 88-93. |

| [17] |

Xu LH, Fang JP, Xu HG, et al. Evaluation of hepatic iron overload in Chinese children with beta-thalassemia major[J]. Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 2011, 28(8): 702-7. DOI:10.3109/08880018.2011.603820 |

| [18] |

Sun L, Wang N, Chen Y, et al. Unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for patients with beta-thalassemia major based on a novel conditioning regimen[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019, 25(8): 1592-6. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.03.028 |

| [19] |

Tisdale J. Improvements in haploidentical transplantation for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassaemia[J]. Lancet Haematol, 2019, 6(4): e168-e69. DOI:10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30045-6 |

| [20] |

Musumeci M, Maccari S, Sestili P, et al. The C57BL/6 genetic background confers cardioprotection in iron-overloaded mice[J]. Blood Transfus, 2013, 11(1): 88-93. |

| [21] |

Tsay J, Yang Z, Ross FP, et al. Bone loss caused by iron overload in a murine model: importance of oxidative stress[J]. Blood, 2010, 116(14): 2582-9. DOI:10.1182/blood-2009-12-260083 |

| [22] |

柴笑, 赵明峰, 李德冠, 等. 小鼠铁过载模型的建立及其对骨髓造血功能的影响[J]. 中国医学科学院学报, 2013, 35(5): 547-52. DOI:10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2013.05.012 |

| [23] |

Strocchio L, Locatelli F. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in thalassemia[J]. Hematol Oncol Clin NorthAm, 2018, 32(2): 317-28. DOI:10.1016/j.hoc.2017.11.011 |

| [24] |

John MJ, Mathew A, Philip CC, et al. Unrelated and related donor transplantation for beta-thalassemia major: A single-center experience from India[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2018, 22(5): e13209. DOI:10.1111/petr.13209 |

| [25] |

Lin TL, Wang PN, Kuo MC, et al. Cyclophosphamide plus granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization in patients with multiple myeloma[J]. J Clin Apher, 2016, 31(5): 423-8. DOI:10.1002/jca.21421 |

| [26] |

Winkelmann N, Desole M, Hilgendorf I, et al. Comparison of two dose levels of cyclophosphamide for successful stem cell mobilization in myeloma patients[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2016, 142(12): 2603-10. DOI:10.1007/s00432-016-2270-9 |

| [27] |

Fujii H, Luo ZJ, Kim HJ, et al. Humanized chronic graft-versus-host disease in NOD-SCID il2rgamma-/- (NSG) mice with G-CSFmobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells following cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7): e133216. |

| [28] |

Juaristi JA, Aguirre MV, Todaro JS, et al. EPO receptor, Bax and Bclx(L) expressions in murine erythropoiesis after cyclophosphamide treatment[J]. Toxicology, 2007, 231(2-3): 188-99. DOI:10.1016/j.tox.2006.12.004 |

| [29] |

Craddock CF, Apperley JF, Wright EG, et al. Circulating stem cells in mice treated with cyclophosphamide[J]. Blood, 1992, 80(1): 264-9. DOI:10.1182/blood.V80.1.264.264 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40