2. Medical Imaging Center, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

3. Institute of Mental Health, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

2. 南方医科大学南方医院 医学影像中心,广东 广州 510515;

3. 南方医科大学精神健康研究院,广东 广州 510515

Wake-up stroke (WUS) is defined as stroke occurring during sleep, which occurs in about 1 out of 10 stroke patients. So far only rare case series were reported to describe the results of thrombectomies for stent retrieval in patients with WUS[1, 2]. The DAWN (DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo) trial revealed that patients with stroke due to occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery or the proximal middle cerebral artery could benefit from thrombectomy performed 6-24 h after stroke with a mismatch between the clinical deficit and the infarct volume[3].

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is a non-contrast brain perfusion method in patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS)[4]. Nevertheless, gadolinium contrast agents used in ASL may cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, which renders it a contraindication in some patients with stroke[4]. Perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), first described nearly 20 years ago [5], remains the mainstay of magnetic resonance (MR)-based examinations for stroke. The mismatch between PWI and diffused-weighted imaging (DWI) indicates the presence of salvageable tissue that can be rescued by prompt recanalization[6].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the outcomes of WUS patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) of anterior circulation, who were selected for intervention based on the mismatch between ASL and DWI Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) on admission MR scans and were treated with stent retrievers.

PATIENTS AND METHODSThis study was performed at the Department of Neurology, Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China) between September, 2016 and November, 2017 under approval by the Nanfang Hospital Ethics Committee. All the patients who were presented directly or transferred to our stroke center underwent a similar imaging protocol, which consisted of non-contrast brain CT to exclude hemorrhage followed by brain MRI examinations including T1, T2, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), DWI, and ASL scans. The MRI data were acquired on a 3-T MRI scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). ASL was conducted using the protocol described by Dai et al[7, 8].

All the patients with suspected LVO were considered candidates for endovascular treatment. In this study, the patients were deemed elegible for thrombectomy based on the following criteria: (1) WUS with the time of last-known normal to arrival (hospital admission) >6 h; (2) presence of proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion confirmed by MRA; 3) mismatch of ASPECTS based on DWI and ASL; and (4) informed consent to thrombectomy using Solitaire FR (Covidien, Michigan, USA). The patients who did not have an independently modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score >2 at baseline were excluded.

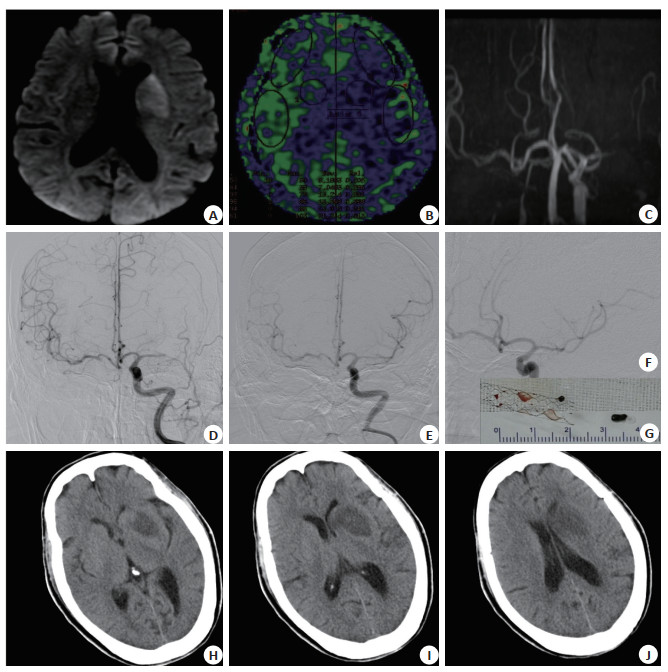

In this pragmatic study, the radiographic assessment of ASPECTS based on DWI and ASL images was designed for rapid clinical decisions. The DWIASPECTS and ASL-ASPECTS scores were assessed by a radiologist with 5 years of experience, and the difference between the two scores defined the mismatch (a higher score indicated a greater mismatch; Fig. 1). Between September, 2016 and August, 2017, 12 patients were seleceted for this study and data were collected from their digital records including the demographic data, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score at admission and discharge, the time of last-known normal before going to sleep, the time of symptom discovery on awakening, the time of CT imaging, and the time of femoral artery puncture. A successful recanalization was defined as a thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (TICI) score of 2b-3. The neurological functions were quantified by mRS score at 90 days. A favorable outcome was defined as a mRS score ≤2. MRI data were re-evaluated by an experienced radiologist with over 10 years of experience, who was blinded to the clinical data.

|

Fig.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) images of a 72- year old female patients presented to our stroke center with dysarthria and weakness of the right arm and leg. MRI scan was obtained 7 h from last known normal. The DWI-ASPECTS was 8 (A shows DWI hyperintensity of the lentiform nucleus) and the ASL-ASPECTS was 5 due to hypoperfused lentiform nucleus, anterior middle cerebral artery (MCA) cortex (M1), MCA cortex lateral to the insular ribbon (M2) and posterior MCA cortex (M3) (B). The mismatch between DWI-ASPECTS and ASL-ASPECTS was 3. MRA indicated proximal occlusion of the left MCA (C). DSA confirmed the occlusion of the left M1 segment of the MCA (D). Recanalization of the MCA was achieved (E, F). After successful thrombectomy with Solitair FR revascularization device (6×30 mm) (G). About 24 h after the operation, cranial CT scan showed hypointensity of the left lentiform nucleus (H-J). |

Data analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS, IL, USA). The normally distributed continuous variables are presented as Mean±SD, and the non-normally distributed variables as the median; the categorical variables are shown as absolute frequencies or percentages. The Wilcoxon rank test was used to analyze the non-normally distributed variables. The significance level for all bivariate and multiple analyses was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTSTwelve patients met the inclusion criteria over the 17-month study period. Tab. 1 presents the detailed clinical data and imaging findings of these patients. This cohort consisted of 5 male and 7 female patients with a median age of 64.5 (range 35-85) years. The comorbidities of the patients included hypertension (6/ 12; 50%), hyperlipidemia (1/12; 8.3%), smoking (3/12; 25%), diabetes (1/12; 8.3%), atrial fibrillation (2/12; 16.7%), and oral anticoagulation (2/12; 16.7%). The median NIHSS score was 10.43 at admission and 3.48 at discharge. The target vessel occlusion was found in the internal carotid artery (ICA) terminus in 2 cases, in M1 segment of the middle cerebral arterial in 8 cases, and in M2 segment in 2 cases. All the procedures led to successful reperfusion (TICI 2b-3), and stent retrievers were used in all cases (Fig. 1). In the 12 cases, the median duration from arrival to recanalization was 154.5 min.

| Tab.1 Clinical and imaging characteristics of the patients |

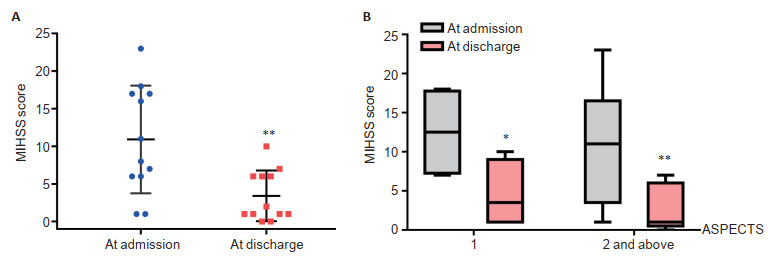

One procedural complication (thrombosis embolism) occurred in 1 patient (No.6), whose condition consequently deteriorated. However, no symptomatic or non-symptomatic hemorrhage was noted. Significant NIHSS shift occurred after the procedures in the other 11 patients (91.7%; P=0.001). A mRS score of ≤2 at 90 days was achieved in 8/12 patients (66.7%). After stratification (mismatch score 1 and ≥2) for DWI-ASL mismatch status (Fig. 2), the difference between the baseline NIHSS and NIHSS at discharge was significant in both groups (P=0.046 and 0.008, respectively).

|

Fig.2 Scatter plot and box plot of the mean NIHSS score of the patients at admission compared with that at discharge. A: NIHSS scores shift at discharge; B: After stratification by the mismatch scores (1 and ≥2), the differences between the NIHSS at the baseline and at discharge were significant in both groups (P=0.046 and 0.008, respectively). The boxes indicate interquartile range; the horizontal lines indicate the median; the whiskers indicate the extreme values; the points and squares indicate NIHSS score values; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. |

In this cohort, 1 patient (8.3%) died one month after discharge. This patient (No.3) had a history of gastrointestinal tumor, and the exact cause of death was not determined as the family members had not noticed any definite progression of stroke symptoms after discharge.

DISCUSSIONWe show here that the simple combination of DWI and ASL findings identified a subgroup of patients with M1/2 segment occlusion, who were likely to benefit from thrombectomy. We demonstrated that thrombectomy led to a statistically significant shift towards a better NIHSS score upon discharge in these patients, who had a favorable prognosis at 90 days. In this study, we found that ASL-ASPECTS provided a semiquantitative approach to estimating hypoperfusion in patients with WUS.

ASL does not require the evaluation of renal function before MR scanning, which saves the door-to-needle time. Although the clinical use of ALS is limited by the low signal-to-noise ratio of the images and the strong dependence of the ASL signal on delayed arterial transit times between the site of labeling and imaging[4], this modality provides much convenience and safety in the management of emergent conditions. In this study, we selected ASL as a substitute for PWI to evaluate the hypoperfusion volume in the stroke patients.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provided class I evidence to support the efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke with LVO and a definite time of onset[2, 9-13]. A previous study showed that in patients receiving intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) for acute stroke due to occlusion in the proximal anterior intracranial circulation, thrombectomy within 6 h after onset improved the functional outcomes of the patients at 90 days[9]. This benefit diminished as the interval increased between the time that the patient was last known normal and the time of thrombectomy [14]. However, some studies demonstrated that patients with a mismatch between the infarcted and hypoperfused brain volume might be rescued by reperfusion of the occluded proximal anterior cerebral vessels even when the reperfusion was performed more than 6 h after the patient was last known normal[3, 15]. In the case of WUS, the uncertain onset time of the stroke limited the performance of thrombectomy. To evaluate the salvageable brain tissue, we used the mismatch between ASL-ASPECTS and DWI-ASPECTS as the indicator for the procedure. Our results showed that a majority of the patients benefited from the procedure, which was in agreement with the findings in the DAWN trial[3].

As a non-contrast brain perfusion technique, ASL has the potential to replace PWI due to its convenience in emergency management of the patients. In patients with stroke, a mismatch of DWI and ASL often indicates that the brain tissue is salvageable. The mismatch of PWI and DWI was reported to be an indicator of salvageable tissue that can be rescued by prompt recanalization[6], but this approch requires gadolinium injection and dedicated software, which increases the scan duration[16]. Other evaluation method has also been reported, such as DWI-fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) mismatch as an alternative model for assessing penumbra[16], but FLAIR images do not well represent the perfusion areas. The use of the mismatch of ASL-ASPECTS and DWI-ASPECTS provides a semiquantitative method for evaluating the feasility of thrombectomy, which does not require a contrast agent and saves the scan time, and can thus be convinient in the management of stroke patients in emergency scenarios.

Different from the previously published trial[9], the patients with low baseline NIHSS scores (< 6) were also selected as candidates for the procedure as long as they met the inclusion criteria. Another study demonstrated that thrombectomy led to a shift towards a low NIHSS in patients with LVO presenting with minimal stroke symptoms, and roughly a quarter of the patients, who were primarily treated with medical therapy, failed to achieve independence at 90 days[17]. We speculate that the mismatch of ASPECTS based on ASL and DWI could aid in selecting the eligible patients for thrombectomy.

To summarize, this study demonstrates a shift towards a lower NIHSS in patients with WUS and M1/M2 occlusions who received thrombectomy with a last-known normal to arrival time >6 h. The mismatch of ASPECTS-ASL with ASPECTS-DWI was used for evaluating the salvageable brain tissue. Most of the patients had significantly lowered NIHSS at discharge, and 66.7% of them had favorable prognoses with a mRS score ≤2. But given the small sample size of patients in this study and the absence of a control group managed with conservative therapy, multicenter randomized clinical trials are required to further elucidate the value of the mismatch of ASPECTS based on ASL and DWI in selecting the patients with AIS for thrombectomy.

AcknowledgementsWe thank all the patients and their family members for their generosity and participation in this study.

| [1] |

Mokin M, Kan P, Sivakanthan S, et al. Endovascular therapy of wakeup strokes in the modern era of stent retriever thrombectomy[J]. J Neurointerv Surg, 2016, 8(3): 240-3. DOI:10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011586 |

| [2] |

Konstas AA, Minaeian A, Ross IB. Mechanical thrombectomy in wakeup strokes:a case series using alberta stroke program early CT score (ASPECTS) for patient selection[J]. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2017, 26(7): 1609-14. DOI:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.02.024 |

| [3] |

Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 378(1): 11-21. |

| [4] |

Zaharchuk G. Better late than never:the long journey for noncontrast arterial spin labeling perfusion imaging in acute stroke[J]. Stroke, 2012, 43(4): 931-2. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644344 |

| [5] |

Rosen BR, Belliveau JW, Vevea JM, et al. Perfusion imaging with NMR contrast agents[J]. Magn Reson Med, 1990, 14(2): 249-65. DOI:10.1002/mrm.1910140211 |

| [6] |

Albers GW, Thijs VN, Wechsler L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging profiles predict clinical response to early reperfusion:the diffusion and perfusion imaging evaluation for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE) study[J]. Ann Neurol, 2006, 60(5): 508-17. DOI:10.1002/ana.20976 |

| [7] |

Lou X, Yu S, Scalzo F, et al. Multi-delay ASL can identify leptomeningeal collateral perfusion in endovascular therapy of ischemic stroke[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(2): 2437-43. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.13898 |

| [8] |

Dai W, Garcia D, de Bazelaire C, et al. Continuous flow-driven inversion for arterial spin labeling using pulsed radio frequency and gradient fields[J]. Magn Reson Med, 2008, 60(6): 1488-97. DOI:10.1002/mrm.21790 |

| [9] |

Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs.t-PA alone in stroke[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(24): 2285-95. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 |

| [10] |

Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(24): 2296-306. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 |

| [11] |

Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(11): 1019-30. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 |

| [12] |

Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(11): 1009-18. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 |

| [13] |

Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(1): 11-20. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 |

| [14] |

Saver JL, Goyal M, van der Lugt A, et al. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke:a meta-analysis[J]. JAMA, 2016, 316(12): 1279-88. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.13647 |

| [15] |

Jovin TG, Liebeskind DS, Gupta R, et al. Imaging-based endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke due to proximal intracranial anterior circulation occlusion treated beyond 8 hours from time last seen well:retrospective multicenter analysis of 237 consecutive patients[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42(8): 2206-11. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604223 |

| [16] |

Legrand L, Tisserand M, Turc G, et al. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery vascular hyperintensities-diffusion-weighted imaging mismatch identifies acute stroke patients most likely to benefit from recanalization[J]. Stroke, 2016, 47(2): 424-7. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010999 |

| [17] |

Haussen DC, Bouslama M, Grossberg JA, et al. Too good to intervene?Thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion strokes with minimal symptoms:an intention-to-treat analysis[J]. J Neurointerv Surg, 2017, 9(10): 917-21. DOI:10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012633 |

2020, Vol. 40

2020, Vol. 40