肝纤维化是多种慢性肝病发展为肝硬化的中间过程,早期有效的抗纤维化治疗能控制疾病发展,降低病死率。目前已有一些药物用于肝纤维化的治疗[1-2],但各种药物的疗效有限并具有不同程度的不良反应。因此,寻找安全有效的天然化合物是治疗肝纤维化的重点。

染料木黄酮是一种功能活性很强的植物化学物,其具有广泛的药理活性[3],其中就包括抗炎、抗氧化和抑制纤维化的作用[4-7]。由于其天然无毒的特性,染料木黄酮是一种具有广泛应用前景的抗纤维化药物。已有研究证实染料木黄酮可以明显减轻肝脏的纤维化程度[8-9]。并且在细胞水平发现染料木黄酮可以抑制HSC细胞激活[10-11]。但是,染料木黄酮抑制HSC细胞活化的分子机制尚不清楚。因此,本研究主要通过PPAR-γ调控的细胞自噬探索染料木黄酮对HSC细胞的影响,为其临床应用提供实验依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料HSC-T6细胞由Dr. Scott Friedman(Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY)惠赠,表型为活化的HSC,具有纤维化特性。染料木黄酮(Sigma);DMEM(Gibco);胎牛血清(杭州四季青公司);TRIzol(Invitrogen);血小板衍生生长因子-BB(PDGF-BB)、PPAR-γ inhibitor T0070907(Selleck Chemicals);3-MA(Sigma);1(I)collagen、-SMA一抗、p62一抗、LC3一抗、PPAR-γ一抗(Cell Signaling Technology);CO2培养箱(Thermo);高速冷冻离心机(Thermo);倒置相差显微镜(Zeiss);凝胶成像分析系统、低压电泳仪(Bio-Rad)。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 细胞培养将冷冻保存于超低温冰箱中的HSCT6复苏后接种于含100 mL/L胎牛血清的高糖DMEM培养液中,37 ℃、50 mL/L CO2条件下培养。当细胞呈单层致密状时,采用2.5 g/L胰蛋白酶消化后传代。每次试验均在呈指数生长的细胞中进行。

1.2.2 蛋白质免疫印记法分析蛋白表达HSC-T6细胞分别加入0、0.5、5、50 µmol/L的染料木黄酮,培养48 h后,提取细胞总蛋白,做SDS-PAGE电泳,将蛋白转移至硝酸纤维滤膜上。膜用体积分数为5%的脱脂奶粉封闭1h,加入各分子的抗体,4 ℃过夜。TBST漂洗3次,加入过氧化酶标记山羊抗兔IgG(1:5000),置于水平脱色摇床上孵育2 h,TBS漂洗3次,ECL光化学法显色。凝胶成像分析系统分析扫描,测定各条带积分光密度值,计算目的条带与内参照的光密度比值。

1.2.3 统计学方法采用SPSS20.0软件进行统计学分析,单因素方差分析,各组数据以均数±标准差表示,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 染料木黄酮在体外抑制PDGF-BB诱导的HSC活化HSC活化标志物,平滑肌肌动蛋白(-SMA),1 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白[1(I)collagen]的表达均显着上调(图 1A、B)。Western印迹分析显示用染料木黄酮处理后,显著抑制了HSC活化标记物-SMA,1(I)collagen的表达。

|

图 1 染料木黄酮对HSC细胞增殖的影响 Fig.1 Effect of genistein on the proliferation of cultured hepatic stellate cells. A: Expression of -SMA and 1(I) collagen in HSC cells detected by Western blotting; B: Analysis of relative expression of the proteins. *P < 0.05 vs control group, #P < 0.05 vs PDGF-BB group |

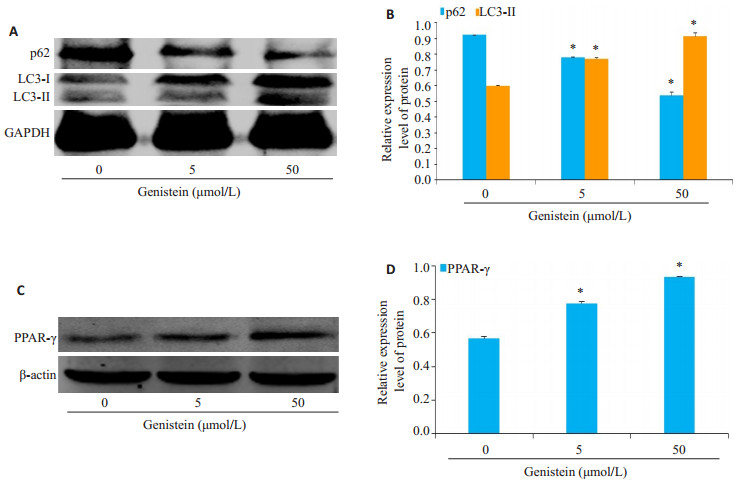

染料木黄酮处理以浓度依赖性地促进了HSCs自噬标记LC3Ⅱ蛋白的表达,还以浓度依赖的方式显著降低了泛素结合蛋白p62的表达(图 2A、B)。同时,PPAR-γ蛋白的表达水平随着染料木黄酮刺激浓度的增大而明显增加(图 2C、D)。

|

图 2 染料木黄酮对PPAR-γ调控的自噬通路的影响 Fig.2 Effect of genistein on the activation of autophagy in HSC-T6 cells. A: Expression of p62 and LC3-II in HSC-T6 cells detected by Western blotting; B: Analysis of relative expression of the proteins; C: Expression of PPAR-γ in HSCT6 cells detected by Western blotting; D: Analysis of relative expression of the protein. *P < 0.05 vs control group |

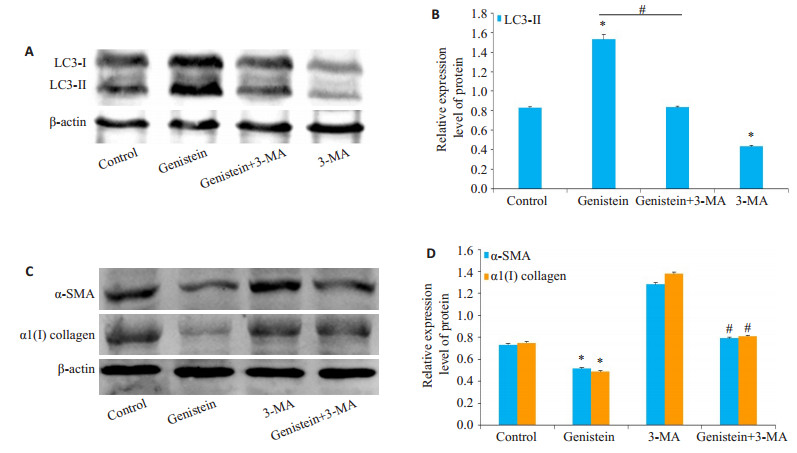

蛋白质免疫印迹分析表明,与对照组相比,Genistein处理显着增加LC3Ⅱ蛋白的表达,但自噬特异性抑制剂3-MA处理后削弱了Genistein对自噬的激活强度(图 3A、B)。用染料木黄酮处理显著降低了HSC活化标记蛋白-SMA和1(I)collagen的表达,而3-MA处理后显著损害了染料木黄酮抑制HSC活化的能力(图 3C、D)。

|

图 3 自噬在染料木黄酮抑制HSC激活过程中的作用 Fig.3 Role of autophagy in mediating genistein-induced inhibition of HSC activation. A: Expression of LC3-II in HSC-T6 cells detected by Western blotting; B: Analysis of the relative expression of LC3-II protein; C: Expression of -SMA and 1(I) collagen in HSC-T6 cells detected by Western blotting; D: Analysis of relative expression of the proteins. *P < 0.05 vs control group, #P < 0.05 vs genistein group |

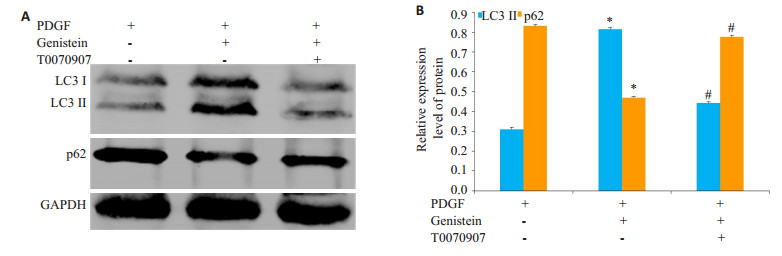

蛋白质免疫印迹分析表明,与对照组相比,染料木黄酮处理显着增加LC3Ⅱ蛋白的表达,但10 nmol/L T0070907处理后LC3Ⅱ蛋白的表达明显降低(图 4A、B)。同样,染料木黄酮处理显着降低了泛素结合蛋白p62的表达,但10 nmol/L T0070907处理后p62蛋白的表达明显增加(图 4A、B)。

|

图 4 PPAR-γ在染料木黄酮激活HSC自噬过程中的作用 Fig.4 Role of PPAR-γ in activating autophagy in genistein-treated HSCs. A: Expressions of p62 and LC3-II in HSC cells detected by Western blotting; B: Analysis of relative expression of the proteins. *P < 0.05 vs control group, #P < 0.05 vs genistein group |

肝纤维化是由许多慢性肝损伤引起的肝脏组织代偿性反应,若得不到有效治疗,常常会发展为肝硬化,肝功能衰竭,门静脉高压和肝细胞癌[1]。肝移植是晚期肝纤维化患者唯一可用的治疗方法[12],而肝纤维化在一定程度上是可逆的。因此,探讨抗纤维化治疗的方案对于肝脏疾病的防治具有重大意义[13-16]。有研究发现,染料木黄酮可以抑制酒精、高脂饮食等各种原因引起的肝纤维化的进程。而染料木黄酮作为大豆异黄酮中的一种主要活性因子,广泛存在于豆科植物中,并具有多种重要的生物活性,包括抗炎、抗氧化、防治疗骨质疏松和抗肿瘤等作用[17-20]。染料木黄酮除了来源广泛外,还具有低毒性的优点,因此研究其肝脏保护作用具有重要的实际意义。

为了研究染料木黄酮抑制HSC细胞激活的活性,我们利用血小板衍生生长因子-BB (PDGF-BB)在体外构建HSC活化的细胞模型[10-11],观察染料木黄酮对其抑制效应。结果发现染料木黄酮作用后显著抑制了HSC细胞活化标志蛋白-SMA、1(I)collagen的表达水平。这就表明,染料木黄酮可能通过抑制HSC细胞活化,发挥抑制肝纤维化的作用,然而具体是通过怎样的分子机制,课题组进行了进一步的实验研究。

PPAR-γ在HSC细胞病理学过程中发挥着重要作用。Miyahara等[6]发现在活化的HSC中PPAR-γ的表达明显降低,当加入PPAR-γ激活剂后则显著抑制HSC的激活并促进了HSC的凋亡。同时,染料木黄酮已被证实是PPAR-γ的一种天然配体[8],通过诱导PPAR-γ依赖的基因表达、调控PPAR-γ相关信号通路发挥重要的生理作用[11]。而我们的研究发现,染料木黄酮可以显著提高PPAR-γ的蛋白表达水平。这就表明,在HSC细胞内,染料木黄酮确实可以激活PPAR-γ,并通过其发挥作用。自噬作为抗肝纤维化的防御机制已经积累了大量的证据[21-24]。激活自噬可以改善肝纤维化的炎症微环境,并导致活化的HSC细胞衰老,促进HSC细胞凋亡,从而减轻肝脏的纤维化损伤[24-26]。PPAR-γ作为一个转录因子,可以调控细胞内自噬通路的激活[27-29]。有研究报道,激活PPAR-γ可以调控下游靶基因PTEN的表达,抑制Akt-mTOR信号通路进而激活细胞自噬,同时,PPAR-γ还可以促进Bcl-2磷酸化,促进其从Beclin1解离,从而导致自噬发生[27, 30]。在目前的研究中,我们发现染料木黄酮处理后,HSC细胞内自噬相关蛋白LC3Ⅱ的表达表现出与PPAR-γ同样的增长趋势,并且利用T0070907抑制PPAR-γ的活性后,细胞自噬水平也受到了明显抑制。同时,为了验证自噬在染料木黄酮拮抗肝纤维化过程中的作用,我们利用自噬抑制剂3MA抑制染料木黄酮增加的HSC细胞自噬水平后,发现染料木黄酮抑制HSC活化的活性也受到了明显抑制。所有这些结果证明,染料木黄酮可以通过激活PPAR-γ调控的自噬通路抑制HSC增殖从而发挥抗纤维化的作用。尽管我们的数据表明染料木黄酮诱导的抗纤维化作用与自噬激活之间存在直接联系,但不能消除可能导致染料木黄酮保护作用的其他信号分子。

总之,这些结果提供了一个机制证据,即在肝纤维化中,染料木黄酮诱导的保护作用与PPAR-γ调控的自噬的激活有关。

| [1] |

Sircana A, Paschetta E, Saba F, et al. Recent insight into the Role of fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(7): E1745. DOI:10.3390/ijms20071745 |

| [2] |

Incir S, Bolayirli IM, Inan O, et al. The effects of genistein supplementation on fructose induced insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation[J]. Life Sci, 2016, 158: 57-62. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2016.06.014 |

| [3] |

Ganai AA, Husain M. Genistein attenuates D-GalN induced liver fibrosis/chronic liver damage in rats by blocking the TGF-/Smad signaling pathways[J]. Chem Biol Interact, 2017, 261: 80-5. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.11.022 |

| [4] |

Huang Q, Huang R, Zhang S, et al. Protective effect of genistein isolated from Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides on hepatic injury and fibrosis induced by chronic alcohol in rats[J]. Toxicol Lett, 2013, 217(2): 102-10. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.12.014 |

| [5] |

黄艳, 黄成, 李俊. 肝纤维化病程中Kupffer细胞分泌的细胞因子对肝星状细胞活化增殖、凋亡的调控[J]. 中国药理学通报, 2010, 26(1): 9-13. |

| [6] |

Miyahara T, Schrum L, Rippe R, et al. Peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptors and hepatic stellate cell activation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2000, 275(46): 35715-22. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M006577200 |

| [7] |

刘瑞, 陈桂泓, 徐伶俐, 等. 荔枝核总黄酮及罗格列酮对大鼠肝星状细胞HSC-T6 PPAR-γ和CTGF表达的影响[J]. 实用医学杂志, 2016, 32(3): 344-7. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2016.03.002 |

| [8] |

韦红梅.大豆异黄酮激活PPARγ促进人前列腺癌DU-145细胞凋亡的作用及其机制[D].第三军医大学, 2012.

|

| [9] |

Xiang Q, Lin G, Fu X, et al. The role of peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor-gamma and estrogen receptors in genisteininduced regulation of vascular tone in female rat aortas[J]. Pharmacology, 2010, 86(2): 117-24. DOI:10.1159/000315065 |

| [10] |

Zhang Z, Zhao S, Yao Z, et al. , Autophagy regulatesturnover of lipid droplets via ROS-dependent Rab25 activation in hepatic stellatecell[J]. Redox Biol, 2017, 11: 322-34. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.021 |

| [11] |

Thoen LF, Guimarães EL, Dollé L, et al. A role for autophagy during hepatic stellate cell activation[J]. J Hepatol, 2011, 55(6): 1353-60. |

| [12] |

Cascales-Campos PA, Romero PR, Schneider MA, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patientswith hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation. Useful, necessaryor irrelevant?[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2017, 91: 155-9. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.03.013 |

| [13] |

Li Y, Zhu M, Huo Y, et al. Anti-fibrosis activity of combination therapy with epigallocatechin gallate, taurine and genistein by regulating glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and ribosomal and lysosomal signaling pathways in HSC- T6 cells[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2018, 16(6): 4329-38. |

| [14] |

Yoo NY, Jeon S, Nam Y, et al. Dietary supplementation of genistein alleviates liver inflammation and fibrosis mediated by a methioninecholine-deficient diet in db/db mice[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2015, 63(17): 4305-11. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00398 |

| [15] |

Zhuo L, Liao M, Zheng L, et al. Combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate and genistein for protection against hepatic fibrosis induced by alcohol in rats[J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2012, 35(10): 1802-10. DOI:10.1248/bpb.b12-00548 |

| [16] |

Cao W, Li Y, Li M, et al. Txn1, Ctsd and Cdk4 are key proteins of combination therapy with taurine, epigallocatechin gallate and genistein against liver fibrosis in rats[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2017, 85: 611-9. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.071 |

| [17] |

Carlos-Reyes A, Lopez-Gonzalez JS, Meneses-Flores M, et al. Dietary compounds as epigenetic modulating agents in cancer[J]. Front Genet, 2019, 10: 79. DOI:10.3389/fgene.2019.00079 |

| [18] |

Prietsch RF, Monte LG, Da Silva FA, et al. Genistein induces apoptosis and autophagy in human breast MCF-7 cells by modulating the expression of proapoptotic factors and oxidative stress enzymes[J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2014, 390(1/2): 235-42. |

| [19] |

Ikeda Y, Iki M, Morita A, et al. Intake of fermented soybeans, natto, is associated with reduced bone loss in postmenopausal women: Japanese population-based osteoporosis (JPOS) study[J]. J Nutr, 2006, 136(5): 1323-8. DOI:10.1093/jn/136.5.1323 |

| [20] |

Wang A, Wei J, Lu C, et al. Genistein suppresses psoriasis- related inflammation through a STAT3-NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism in keratinocytes[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2019(69): 270-8. |

| [21] |

Ge MX, He HW, Shao RG, et al. Recent progression in the utilization of autophagy-regulating Nature compound as anti-liver fibrosis agents[J]. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2017, 19(2): 109-13. DOI:10.1080/10286020.2016.1276168 |

| [22] |

Tao LL, Zhai YZ, Di DD, et al. The role of C/EBP-alpha expression in human liver and liver fibrosis and its relationship with autophagy[J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2015, 8(10): 13102-7. |

| [23] |

Yu YQ, M ao, Xiao XM, et al. Autophagy: a new therapeutic target for liver fibrosis[J]. World J Hepatol, 2015(16): 1982-6. |

| [24] |

Qu Y, Zhang QD, Cai XB, et al. Exosomes derived from miR-181-5pmodified adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent liver fibrosis via autophagy activation[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2017, 21(10): 2491-502. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.2017.21.issue-10 |

| [25] |

Zhang ZL, Yao Z, Zhao SF, et al. Interaction between autophagy and senescence is required for dihydroartemisinin to alleviate liver fibrosis[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2017, 8: e2886. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2017.255 |

| [26] |

Yang N, Dang SS, Shi JJ, et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester attenuates liver fibrosis via inhibition of TGF-beta 1/Smad3 pathway and induction of autophagy pathway[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2017, 486(1): 22-8. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.057 |

| [27] |

To KK, Wu WK, Loong HH. PPARgamma agonists sensitize PTENdeficient resistant lung cancer cells to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors by inducing autophagy[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2018, 823: 19-26. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.01.036 |

| [28] |

Zhong J, Gong W, Chen J, et al. Micheliolide alleviates hepatic steatosis in db/db mice by inhibiting inflammation and promoting autophagy via PPAR-gamma-mediated NF- small ka, CyrillicB and AMPK/mTOR signaling[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2018(59): 197-208. |

| [29] |

Rovito D, Giordano C, Vizza D, et al. Omega-3 PUFA ethanolamides DHEA and EPEA induce autophagy through PPAR gamma activation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2013, 228(6): 1314-22. DOI:10.1002/jcp.v228.6 |

| [30] |

Qin H, Tan W, Zhang Z, et al. 15d-prostaglandin J2 protects cortical neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation injury: involvement of inhibiting autophagy through upregulation of Bcl-2[J]. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2015, 35(3): 303-12. DOI:10.1007/s10571-014-0125-y |

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39