2. 暨南大学第二临床医学院//深圳市人民医院病理科,广东 深圳 518020;

3. 南方科技大学第一附属医院//深圳市人民医院 放疗科,广东 深圳 518020;

4. 南方医科大学 南方医院病理科,广东 广州 510515;

5. 南方医科大学 基础医学院病理学系,广东 广州 510515

2. Department of Pathology, Shenzhen People's Hospital/Second Clinical College of Jinan University, Shenzhen 518020, China;

3. Department of Radiation Oncology, Shenzhen People's Hospital/First Affiliated Hospital of Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518020, China;

4. Department of Pathology, Nanfang Hospital, Department of Pathology, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

5. Department of Pathology, Nanfang Hospital, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

肿瘤干细胞(CSC)学说认为CSC是肿瘤发生、转移和复发的根源,这群细胞有自我更新能力、无限增殖、多向分化潜能的干细胞特性[1]。CSC的研究模式是在确定白血病肿瘤干细胞[2]后建立的,细胞亚群从肿瘤细胞群中分离出来,具有自我更新和分化能力,少量细胞(一般为数个到102细胞)移植至NOD/SCID免疫缺陷小鼠体内能够成瘤,且能分化与来源肿瘤表型特征一致的肿瘤细胞,就被认为是CSC[2-3]。按照这一研究模式,相继发现了其它实体瘤CSC的存在。在结直肠癌中也认为存在一群分化缓慢、具有自我更新能力和分化潜能的细胞,只有这群细胞才能形成肿瘤,它们是结直肠癌形成的种子和源泉,即结直肠癌肿瘤干细胞学说[5-7]。

O'Brien[4]和Ricci-Vitiani[5]最开始研究结直肠癌CSC,被称为结直肠癌的肿瘤起始细胞,他们认为CD133是结直肠癌干细胞的分子标记物,只有CD133阳性的细胞才具有自我更新和连续成瘤的能力。Dalerba[6]等通过CD44、EpCAM和CD166标记物筛选出新鲜结直肠癌组织中具有CSC特性的细胞。Singh等[7]在人神经上皮性脑肿瘤中分离、培养出脑CSC,为后续其他CSC的培养了提供了方法。Vermeulen等[8]在新鲜结直肠癌组织中的培养出了CSC,并检测这些细胞表达干细胞标记物。

利用特异性标志物通过免疫磁珠或流式进行分选CSC,或通过流式细胞术分选侧群细胞(SP)仍然是目前筛选CSC的主要方法[9-15],但这些方法首先需要确定的CSC细胞膜表面标记物,限制了CSC的多样性,不利于发现新型CSC标志物。国内关于结直肠癌干细胞的研究,主要是从现有细胞株中筛选和鉴定CSC[16-21],没有建立来源于临床结直肠癌患者组织标本的CSC培养和鉴定方法。

本文应用原代培养及无血清培养,在外科手术切除的新鲜结直肠癌组织标本中筛选,有效获得了CSC,通过体外实验和裸鼠皮下成瘤实验,鉴定了CSC的自我更新及分化能力。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料胎牛血清、DMEM高糖培养基、DMEM/F12细胞培养基(Gibco);0.25%胰酶(四季青);胶原酶和透明质酸酶(Sigma);Accutase(eBioscience);B27添加剂、重组人表皮生长因子(EGF)、重组人碱性成纤维生长因子(bFGF)(Invitrogen);白血病抑制因子(LIF)(Millpore);CD133单克隆抗体(Miltenyi);CD44单克隆抗体(Abcam)Tubulin单克隆抗体(Sigma);CK7多克隆抗体(Bioworld);辣根酶标记山羊抗鼠(兔)IgG(H+L)二抗(中杉金桥);蛋白预染Marker(Fermentas);BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit、PVDF膜和化学发光检测试剂盒(Pierce);FITC、TRITC标记的荧光二抗(Santa Cruz);所采用的人结肠癌SW480细胞系来自ATCC(美国组织培养保藏中心),由上海生物细胞所提供。裸鼠购置于南方医科大学动物实验中心,饲养于南方医院SPF动物实验室。本实验遵从动物实验基本管理条例和动物伦理学条例。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 结直肠癌组织的原代培养临床结肠癌患者,男性,65岁,乙状结肠中分化腺癌行肿瘤根治术。从手术切除的标本中取下小块癌组织,在加有500 U/mL青霉素和500 U/mL链霉素的DMEM高糖培养基中漂洗3遍,接种于裸鼠皮下。1个月后,裸鼠皮下形成的肿瘤,用无菌的眼科剪剪碎,加入1 mg/mL的胶原酶和0.5 mg/mL的透明质酸酶消化液,在37 ℃摇床中消化1 h,离心去上清,PBS重悬2次后,用50 μm滤网过滤细胞悬液。通过低血清培养和多次贴壁法去除纤维细胞,获得较纯的肿瘤细胞。本研究符合医学伦理学标准并得到南方医院伦理委员会批准,并取得受试者知情同意。

1.2.2 CSC的培养和诱导分化配制无血清培养基:DMEM/F12含B27(10 ng/mL)、EGF(20 ng/mL)、bFGF(10 ng/mL)和LIF(10 ng/mL);配制含血清培养基:DMEM高糖培养基含10%胎牛血清。将肿瘤细胞制成单细胞悬液,接种于96孔板(100 μL/孔),标记含有1个细胞的培养孔。观察并记录单个原代培养的肿瘤细胞在无血清培养基中形成CSC的过程。将CSC放在含血清培养基中,诱导分化并观察细胞形态。

1.2.3 软琼脂集落形成实验37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱里培养14 d,用Giemsa液染色15 min;在倒置显微镜下观察并计数所形成的克隆(≥50个细胞计为克隆),平板克隆形成率=形成克隆数/接种细胞数×100%,实验重复3次。

1.2.4 低数量级细胞裸鼠皮下成瘤实验无血清培养基中获得的肿瘤细胞球,分别以500、1000、5000、10 000个接种到4周的BALB/c-nu裸鼠的背部皮下。因应用有血清培养基原代培养的临床结直肠癌组织,获得的肿瘤细胞中有少量纤维细胞,无法去除,本实验用同样数量级别的SW480细胞悬液为对照组。5周后处死裸鼠观察皮下瘤形成情况。

1.2.5 免疫表型的检测Western blot方法鉴定CD133、CD44、CK7的表达鼠抗人CD133单克隆抗体(1: 2000)、CD44(1:1000)、兔抗人CK7多克隆抗体(1:500)和鼠抗人β-tubulin单克隆抗体(1:1000)4 ℃过夜,二抗在室温杂交1 h。化学发光试剂检测目标蛋白质的表达。

激光共聚焦显微镜观察细胞免疫荧光检测CD133、CD44的表达。

一抗鼠抗人CD133单克隆抗体(1:300)、CD44单克隆抗体(1:200),荧光标记二抗(FITC、TRITC)(1:100),用5 μg/mL DAPI染液衬染细胞核,激光共聚焦显微镜下观察。

1.2.6 统计学方法采用SPSS13.0软件处理,计数资料采用单因素方差分析及Bonferroni两两比较的方法,P < 0.05表示差异具有统计学意义。

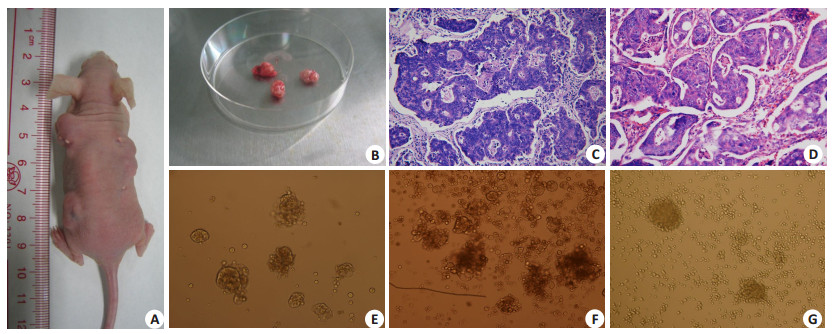

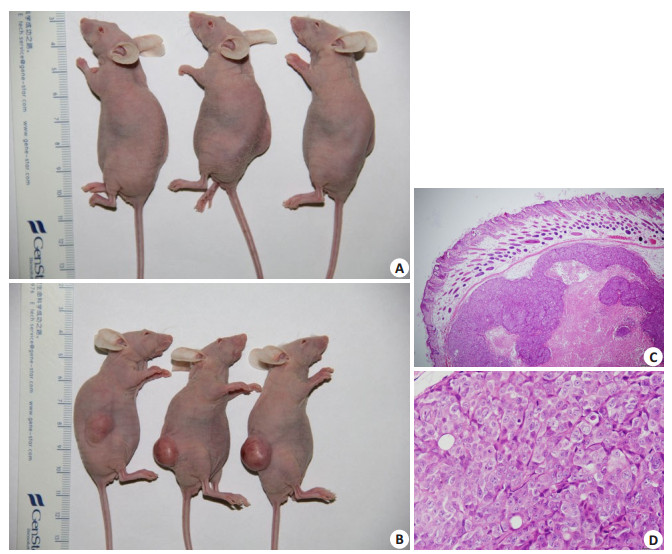

2 结果 2.1 结直肠癌组织的原代培养手术切除的结直肠癌组织在裸鼠皮下形成皮下瘤,原代培养及纯化后肿瘤细胞(图 1)结直肠癌患者癌组织块植入裸鼠皮下(A),摘除肿瘤呈椭球形(B),患者癌组织的病理形态(HE,200倍)(C)与裸鼠皮下瘤(HE,200倍)(D)组织形态类似。癌组织纯化培养后(消除成纤维细胞),形成了肿瘤细胞克隆球(E~F,200倍;G,100倍)。

|

图 1 临床结直肠癌组织肿瘤细胞的分离及其形态表现 Fig.1 Isolation of colorectal cancer xenografts from a nude mouse and pathological observation of the tumor tissues. The colorectal cancer tissues were implanted subcutaneously in nude mice (A), and the ellipsoidal xenografts were harvested 1 month later (B). HE staining was used for pathological examination of the clinical specimens of the cancer tissue (C) and the subcutaneous xenograft in nude mice (D) (×200). Figures E to F (×200) and G (×100) show the tumor cell clones formed after purification and adherent culture of the tumor cells to eliminate fibroblasts |

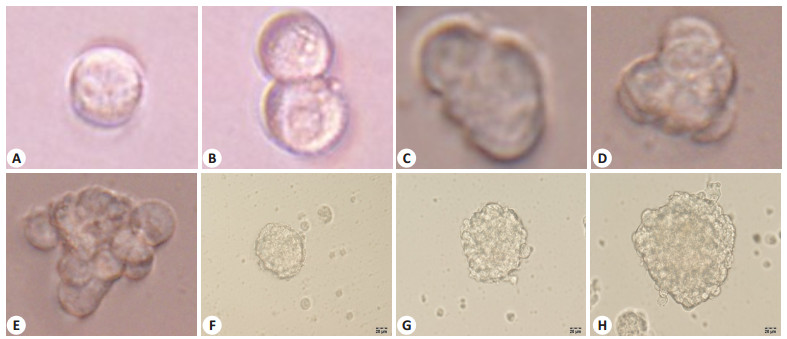

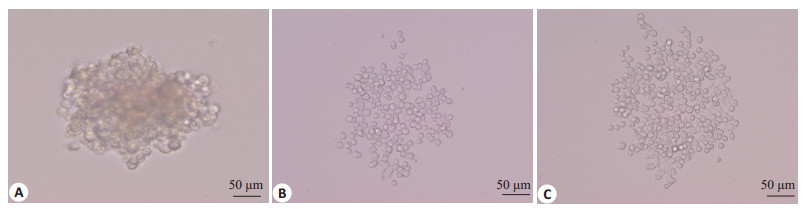

共计接种8块96孔板(共768孔),培养结直肠癌原代培养的单细胞源性肿瘤细胞球克隆8个(clone sphere1~8),肿瘤细胞球克隆形成率为1.04%(8/768)。用无血清培养基培养的单细胞悬液,形成了肿瘤细胞球,其动态生长、增殖、增大如图所示(图 2)。肿瘤细胞球用有血清培养基培养,诱导其分化,24 h后贴壁生长,周边的细胞呈长梭形或短梭形生长,中间的细胞呈悬浮生长,48 h后所有细胞呈贴壁生长(图 3)。

|

图 2 倒置显微镜观察肿瘤干细胞的体外克隆球的形成 Fig.2 Formation of clonal spheres by cancer stem cells in vitro observed under an inverted microscope. The number of tumor cell cells and the volume of the clone sphere increase with time showing the expansion of the tumor stem cell sphere. A: Day 1; B: Day 3; C: Day 5; D: Day 8; E: Day 12; F: Day 15; G: Day 18; H: Day 22; 8D(A-D: ×400, E-H: ×200) |

|

图 3 在含血清培养基中肿瘤干细胞球分化生长的过程 Fig.3 Cancer stem cell differentiation and growth in serum-containing medium. The cells differentiate into epithelioid and spindleshaped tumor cells (×200) A: 0 h; B: 24 h; C: 48 h |

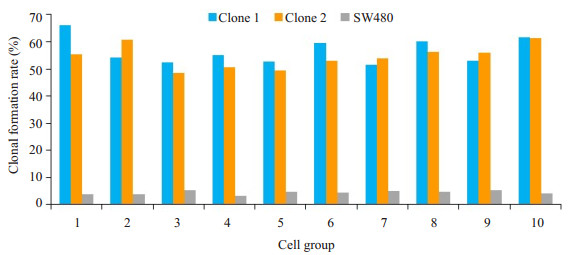

软琼脂集落形成实验统计学分析结果表明,接种相同数量细胞后,原代培养的clone sphere 1和clone sphere 2克隆形成率为56.64%和54.45%,对照组人结直肠癌细胞株SW480的克隆形成率为4.41%,clone sphere 1和clone sphere 2所形成的细胞克隆数量均显著高于SW480细胞(P < 0.01)。3组细胞的总体差别具有显著性(F=598.78,P < 0.01)(表 1、图 4)。

| 表 1 肿瘤干细胞球克隆、SW480细胞克隆形成实验比较 Tab.1 Comparison of clone formation efficiency with CSC and SW480 |

|

图 4 SW480和原代培养肿瘤干细胞软琼脂集落形成实验 Fig.4 Soft agar colony formation experiment of SW480 and primary cultured cancer stem cells. The colony formation rate of clone sphere 1 and clone sphere 2 was 56.64% and 54.45%, respectively, and that of SW480 cells was 4.41% |

来源于原代培养肿瘤细胞克隆球按前述细胞数接种于裸鼠皮下,均形成了皮下瘤,而SW480细胞未形成肿瘤。图 5A示接种500个SW480细胞,裸鼠皮下未形成皮下瘤,图 5B示接种500个原代培养的clone sphere 1,在裸鼠皮下形成了皮下瘤结节,显微镜下观察组织形态仍为腺癌结构(图 5C、D)。

|

图 5 原代培养的肿瘤干细胞裸鼠皮下成瘤实验 Fig.5 Primary cultured cancer stem cells are tumorigenic in nude mice. A: 500 SW480 cells fail to form tumors 35 days after injection in nude mice; B: 500 primary cultured cancer stem cells form subcutaneous tumors 35 days after injection in nude mice; C, D: HE staining of the tumors formed by cancer stem cells in nude mice (C: ×40; D: ×400) |

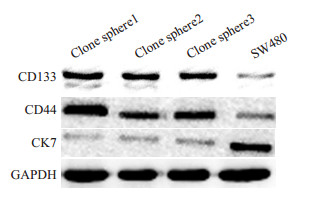

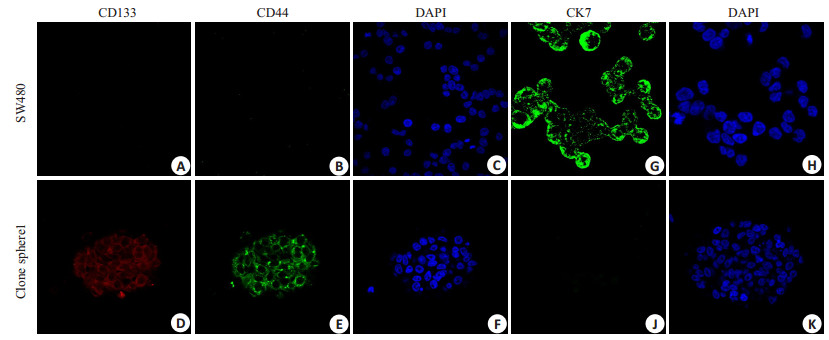

多次免疫印迹杂交结果表明,原代培养的肿瘤细胞球克隆CD133、CD44的表达高于结肠癌SW480细胞系,CK7的表达明显低于SW480(图 6)。免疫荧光检测结果表明,原代培养的肿瘤细胞球克隆强烈表达CD133、CD44而不表达CK7,而结肠癌SW480细胞系强烈表达CK7而不表达CD133、CD44(图 7)。结果显示原代培养的肿瘤细胞球表达结直肠癌CSC的标记物:CD133和CD44。

|

图 6 免疫印迹法检测原代培养的肿瘤干细胞克隆亚系及SW480细胞CD133、CD44、CK7的表达 Fig.6 Expression of CD133, CD44 and CK7 in primary cultured tumor stem cell clone subline and SW480 cells detected by immunoblotting. The expressions of CD133 and CD44 were stronger but CK7 expression was lower in CSCs than in SW480 cells |

|

图 7 免疫荧光检测原代培养的肿瘤干细胞克隆亚系及SW480细胞CD133、CD44、CK7的表达 Fig.7 Expression of CD133, CD44 and CK7 in primary cultured tumor stem cell clone sublines and SW480 cells detected by immunofluorescence. SW480 cells do not express CD133 (A) and CD44 (B), while CSCs strongly express CD133 stained by red (D) and CD44 stained by green (F). SW480 cells strongly express CK7 stained by green (G), while the CSCs do not express CK7 (J). The cell nucle are stained by DAPI in bule (C, F, H, K). The results showed that the expression of CD133 and CD44 in CSC was stronger than that in SW480 |

从临床结直肠癌组织中获得CSC,一直是CSC研究中的难题。我们通过原代培养,有限稀释和无血清培养基筛选,在结直肠癌组织原代培养的肿瘤细胞中,约1.04%的细胞具有克隆球形成能力,这些细胞在体外无血清培养基中能保持未分化的悬浮状态。后续体内外实验鉴定了这些原代培养的肿瘤细胞球具有CSC特性,为结肠癌的深入研究建立良好的细胞模型,有利于结直肠CSC库的建立和抗CSC的治疗。

CSC具有自我更新、诱导分化两大主要特性。无血清培养基中的EGF和bFGF能促进干细胞增殖并维持其干性,有利肿瘤干细胞体外培养及扩增[7, 22]。LIF、B27作为血清替代物,提供了细胞赖以生存的必需营养物质,LIF有利于保持干细胞的未分化状态。我们观察原代培养的肿瘤细胞球在这种培养基中生长缓慢,类似干细胞的增殖特征。血清会诱导CSC分化,肿瘤细胞球加入血清后贴壁分化,成为梭型贴壁生长的细胞,与细胞株培养生长方式一致,提示这些细胞球具有CSC特性并能被诱导分化。

软琼脂集落实验结果表明,原代培养的肿瘤干细胞球比SW480细胞株具有更强的增殖能力。软琼脂集落实验消除了细胞之间相互影响,使单个细胞形成形态明显不同细胞集落克隆,而不利于细胞依赖性强的细胞增殖生长[23]。干细胞能够悬浮生长或在半固体培养基中生长,而普通细胞未附着固体表面就很难生长[24]。体外实验反映了肿瘤干细胞的生物学功能,还需通过动物体内实验鉴定其致瘤能力。鉴定CSC的金标准是少量细胞(通常为102~103个细胞)植入免疫缺陷动物(如裸鼠)体内,模拟干细胞的分化过程,能够分化演变为完整的恶性肿瘤,并具有与原发肿瘤类似的组织学特点[21, 25-26]。裸鼠皮下成瘤实验表明,我们从新鲜结直肠癌组织中,原代培养获得的肿瘤细胞球是结直肠癌CSC,因为500个细胞即可形成皮下瘤,而SW480细胞株在相同数量级却不能形成肿瘤。体内、体外实验表明用原代培养及无血清培养基培养出的细胞球,具有CSC的自我更新和分化潜能,是具有干细胞特性的肿瘤起始细胞。

CD44、CD133被认为是结直肠癌干细胞重要标志物[15, 20, 27-29],CK7可以做为结直肠癌分化标志物[30],我们的研究结果显示原代培养结直肠癌干细胞表达CD133和CD44,不表达CK7,表明克隆球中的绝大部分细胞仍处于未分化状态,且表达CSC标志物。

按照经典的免疫磁珠法或流式法分选CSC,不可避免地使用已知CSC标记物,造成CSC的单一性,难以解释临床结直肠癌患者肿瘤演变的复杂过程。我们的经验显示,原代培养手术切除的结直肠癌标本,可以获得多个CSC克隆(我们从1例患者中获得了8个CSC克隆),虽然体内外实验鉴定这些克隆具有结直肠癌CSC特性,但这些克隆也可能存在CSC的异质性,为结直肠癌CSC生物学行为抑制性的研究和肿瘤个体化治疗,提供了可靠的细胞模型,有利于建立多样性的CSC细胞库,为全面研究结直肠癌的发生发展提供了重要的技术支撑。

| [1] |

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, et al. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells[J].

Nature, 2001, 414(6859): 105-11.

DOI: 10.1038/35102167. |

| [2] |

Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice[J].

Nature, 1994, 367(6464): 645-8.

DOI: 10.1038/367645a0. |

| [3] |

Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions[J].

Nat Rev cancer, 2008, 8(10): 755-68.

DOI: 10.1038/nrc2499. |

| [4] |

O'brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, et al. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice[J].

Nature, 2007, 445(7123): 106-10.

DOI: 10.1038/nature05372. |

| [5] |

Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells[J].

Nature, 2007, 445(7123): 111-5.

DOI: 10.1038/nature05384. |

| [6] |

Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells[J].

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2007, 104(24): 10158-63.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. |

| [7] |

Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors[J].

Cancer Res, 2003, 53(2): 487-8.

|

| [8] |

Vermeulen L, Todaro M, de Sousa Mello F, et al. Single-cell cloning of colon cancer stem cells reveals a multi-lineage differentiation capacity[J].

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(36): 13427-32.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0805706105. |

| [9] |

Heidt DG, Li C, Mollenberg N, et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells[J].

cancer Res, 2006, 130(2): 194-5.

|

| [10] |

Li C, Lee CJ, Simeone DM. Identification of human pancreatic cancer stem cells[J].

Methods Mol Biol, 2009, 568(6): 161-73.

|

| [11] |

Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line[J].

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004, 101(3): 781-6.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0307618100. |

| [12] |

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells[J].

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2003, 100(7): 3983-8.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. |

| [13] |

Feng L, Wu JB, Yi FM. Isolation and phenotypic characterization of cancer stem-like side population cells in colon cancer[J].

Mol Med Rep, 2015, 12(3): 3531-6.

DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3801. |

| [14] |

Mahkamova K, Latar N, Aspinall S, et al. Hypoxia increases thyroid cancer stem cell-enriched side population[J].

World J Surg, 2018, 42(2): 350-7.

DOI: 10.1007/s00268-017-4331-x. |

| [15] |

Fanali C, Lucchetti D, Farina M, et al. Cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer from pathogenesis to therapy: controversies and perspectives[J].

World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(4): 923-42.

DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.923. |

| [16] |

贾健锋, 贺长林. 结直肠肿瘤干细胞体外培养形态、标志物及转移动力学特征[J].

检验医学与临床, 2014(z1): 290-3.

|

| [17] |

李勇, 杨召, 吴妮莎, 等. shRNA干扰KLF4对Lgr5+结直肠癌肿瘤干细胞迁移侵袭的影响及机制[J].

武汉大学学报:医学版, 2018, 39(6): 899-904.

|

| [18] |

胡祥, 程勇, 王吉明, 等. 结肠癌细胞系SW480肿瘤干细胞相关亚群初步分离、鉴定[J].

中国癌症杂志, 2008, 18(7): 496-500.

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3639.2008.07.004. |

| [19] |

成蕾, 肖云峰, 李孝琼, 等. FH535对结直肠癌肿瘤干细胞自我更新及侵袭迁移的抑制作用及机制[J].

中国普通外科杂志, 2018, 27(10): 1288-94.

DOI: 10.7659/j.issn.1005-6947.2018.10.011. |

| [20] |

Zhou Y, Xia L, Wang H, et al. Cancer stem cells in progression of colorectal cancer[J].

Oncotarget, 2018, 9(70): 33403-15.

|

| [21] |

Ramesh P, Kirov AB, Huels DJ, et al. Isolation, propagation, and clonogenicity of intestinal stem cells[J].

Methods Mol Biol, 2018, 11: 1-13.

|

| [22] |

Zhou SL, Ochalek A, Szczesna K, et al. The positional identity of iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells along the anterior-posterior axis is controlled in a dosage-dependent manner by bFGF and EGF[J].

Differentiation, 2016, 92(4): 183-94.

DOI: 10.1016/j.diff.2016.06.002. |

| [23] |

Ye Q, Feng B, Yf P, et al. Expression of γ-synuclein in colorectal cancer tissues and its role on colorectal cancer cell line HCT116[J].

World J Gastroenterol, 2009, 15(40): 5035-43.

DOI: 10.3748/wjg.15.5035. |

| [24] |

Yang K, Tang Y, Habermehl GK, et al. Stable alterations of CD44 isoform expression in prostate cancer cells decrease invasion and growth and alter ligand binding and chemosensitivity[J].

BMC cancer, 2010, 10(1): 16.

DOI: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-16. |

| [25] |

Takemasa I, Ishii H, Haraguchi N, et al. Perspectives on current status and future directions for cancer stem cells theory in gastrointestinal cancer[J].

Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi, 2009, 110(4): 207-12.

|

| [26] |

Wahab S, Islam F, Gopalan V, et al. The identifications and clinical implications of cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer[J].

Clin Colorectal cancer, 2017, 16(2): 93-102.

|

| [27] |

Cherciu I, Bărbălan A, Pirici D, et al. Stem cells, colorectal cancer and cancer stem cell markers correlations[J].

Current health sciences journal, 2015, 40(3): 153-61.

|

| [28] |

Lugli A, Iezzi G, Hostettler I, et al. Prognostic impact of the expression of putative cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD166, CD44s, EpCAM, and ALDH1 in colorectal cancer[J].

Br J cancer, 2010, 103(3): 382-90.

|

| [29] |

Fedyanin M, Anna P, Elizaveta P, et al. Role of stem cells in colorectal cancer progression and prognostic and predictive characteristics of stem cell markers in colorectal cancer[J].

Curr Stem Cell Res Ther, 2017, 12(1): 19-30.

|

| [30] |

Park SY, Kim HS, Hong EK, et al. Expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in primary carcinomas of the stomach and colorectum and their value in the differential diagnosis of metastatic carcinomas to the ovary[J].

Hum Pathol, 2002, 33(11): 1078-85.

DOI: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129422. |

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39