目前我国冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病(CAD)患病率仍处于持续上升阶段,尽管近年来在传统危险因素控制和他汀降低低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)等治疗方面取得巨大进步,仍有大量患者存在心血管事件的残余风险[1-2]。因此,进一步寻找CAD的相关危险因素并加以干预,具有重要意义。脂蛋白(a)[Lp(a)]是一种类低密度脂蛋白的血脂颗粒,主要由富含胆固醇酯的内核和特有的载脂蛋白(a)[Apo(a)]组成,具有基因多态性和长期稳定的特点,在人群中呈偏态分布[3-5]。有研究发现Lp(a)升高与罹患心血管事件风险增加及相关血运重建有关[6-7];尽管也有部分研究认为冠心病患者Lp(a)升高与其致死率无关[8],但Lp(a)在冠心病治疗领域的研究已越来越受重视。另有研究表明不同水平Lp(a)和LDL-C人群罹患CAD风险各有不同[9],Lp(a)是否为导致冠脉狭窄的独立因素仍未定论。因此本文通过研究不同Lp(a)表达水平的人群与CAD风险的关系,及其与LDL-C、冠脉狭窄程度的相关性,探讨其与CAD发生及狭窄严重程度的关系。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象收集2013年1月~2016年12月期间在南方医科大学南方医院就诊住院并符合以下标准的患者531例,所有纳入者均行冠状动脉造影及外周血血脂八项检查。排除标准:既往有冠脉搭桥史、严重瓣膜病、重症心肌炎、严重肝肾功能损害、严重感染性疾病、血液系统性疾病、甲状腺功能异常、肿瘤以及临床数据缺失的患者。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 病史采集所有纳入的研究对象均收集包括年龄、性别、发病时间(胸闷、胸痛),询问吸烟史、高血压及糖尿病史,测量收缩压、舒张压、身高、体质量,计算体质量指数(BMI)。入院后行血常规、血肌酐(Scr)、尿酸(UA)、血脂八项、C反应蛋白(CRP)、糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)等项目检查。

1.2.2 血脂测量方法采用美国Roche全自动生化分析仪测定甘油三酯(TG)、总胆固醇(TC)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(HDL-C)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)、载脂蛋白A-I(apoA-I)、载脂蛋白B(apoB)、载脂蛋白E(apoE)、Lp(a)等脂质指标,试剂盒为美国Roche全自动生化分析仪配套试剂盒,质控及校准品由美国Bio-Rad公司提供。TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C等指标采用酶学方法检测,而apoA-I、apoB、apoE、Lp(a)采用免疫比浊法检测。

1.2.3 冠脉造影冠状动脉造影术由心内科导管室专业医师在标准导管室完成。所有患者均采用Judkins法多体位完成左、右冠状动脉造影,并由2名有经验的医师对其造影结果进行重新评估,以每支冠状动脉血管最严重狭窄程度进行定量评定,主要的冠状动脉包括:左主干、左前降支、左回旋支及右冠状动脉;主要冠脉分支包括:第一对角支、第二对角支、钝缘支、左室后支、后降支。

1.2.4 诊断标准参考2016年中国成人血脂异常防治指南,人群血清Lp(a)浓度以30 mg/dL为切点,高于此水平界定为高Lp(a),否则为低Lp(a)[10]。根据冠状动脉造影结果,证实至少1支心外膜冠状动脉或其主要分支内径狭窄≥50%的患者诊断冠心病;其中,冠心病患者按临床症状的严重程度分为急性冠脉综合征(ACS)组[11]和稳定性心绞痛(SAP)组[12]。根据美国心脏病协会的冠脉分段评价标准,冠心病患者冠脉狭窄程度采用Gensini评分系统进行评价[13],直径狭窄 < 25%计1分,26%~50%计2分,51%~75%计4分,76%~90%计8分,91%~99%计16分,完全闭塞计32分。根据冠状动脉节段乘以相应系数,左主干病变×5;左前降支病变:近端× 2.5,中端×1.5,远端×1;对角支病变:D1×1,D2×0.5,左旋回支病变:近端×2.5,远端×1;后降支×1,后侧支×0.5;右冠状动脉病变:近、中、远和后降支均×1,各狭窄冠脉评分之和即为Gensini评分。

1.2.5 统计学分析应用SPSS19.0统计软件对数据进行统计分析。计量资料采用均数±标准差表示,两组间比较采用两组独立样本t检验;多组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较采用SNK-q检验;计数资料组间采用χ2检验;采用单因素Logistic回归分析冠心病的危险因素,再将这些指标纳入多因素Logistic回归分析;采用双侧检验,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 按照血清Lp(a)分组的临床指标比较高Lp(a)组和低Lp(a)组的血清Lp(a)水平分别为60.15±26.28 mg/dL和14.16±7.66 mg/dL,两组在年龄、性别、BMI、吸烟、高血压和糖尿病史方面无统计学差异(P>0.05);实验室检验指标除CRP(P=0.018)和apoA-I(P=0.030)之外均无明显统计学差异(P>0.05),两组具有可比性(表 1)。

| 表 1 高Lp(a)组(HLPA)和低Lp(a)组(LLPA)患者的临床资料比较 Tab.1 Comparison of the clinical data between the high Lp(a) group(HLPA) and low Lp(a) group(LLPA) |

高低Lp(a)两组的LDL-C分别为3.03±0.88 mmol/L和2.94±0.89 mmol/L,没有统计学差异(P=0.288,表 1);根据LDL-C水平按照四分位法分为C1组(≤ 2.36 mmol/L)、C2组(2.36~2.94 mmol/L)、C3组(2.94~ 3.56 mmol/L)和C4组(>3.56 mmol/L),其组间Lp(a)浓度差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表 2)。

| 表 2 Lp(a)与LDL-C相关性分析 Tab.2 Association of Lp(a) and LDL-C |

单因素Logistic回归分析结果示年龄、性别、吸烟和糖尿病史、HbA1c、Scr、CRP、HDL-C、apoA-I和Lp(a)是冠心病的危险因素;多因素Logistic回归分析提示Lp(a)、LDL-C、年龄和性别是冠心病的独立危险因素。其中,高Lp(a)对冠心病的OR为2.443(P=0.013),Lp(a)水平越高,罹患冠心病的风险亦随之升高(表 3)。

| 表 3 冠心病的危险因素的Logistic回归分析 Tab.3 Logistic regression analysis of the risk factors of CAD |

当LDL-C处于较高水平时,高Lp(a)组有92例罹患CAD,比低Lp(a)组风险更高(P=0.006);在低LDL-C组内,高Lp(a)组人群发生CAD的风险也较低Lp(a)组升高(P=0.020,表 4)。

| 表 4 不同LDL-C条件下Lp(a)与CAD的关系 Tab.4 Association of Lp⑷ with CAD at different levels of LDL-C |

与SAP组相比,ACS组患者血清CRP、TC、LDLC、apoB、Lp(a)、apoE水平更高,吸烟所占比例更高,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05);两组在年龄、性别、BMI、高血压、糖尿病、HbA1c等方面均无统计学差异(P>0.05,表 5)。

| 表 5 不同病例分型冠心病患者临床资料比较 Tab.5 Comparison of the clinical data between SAP group and ACS group |

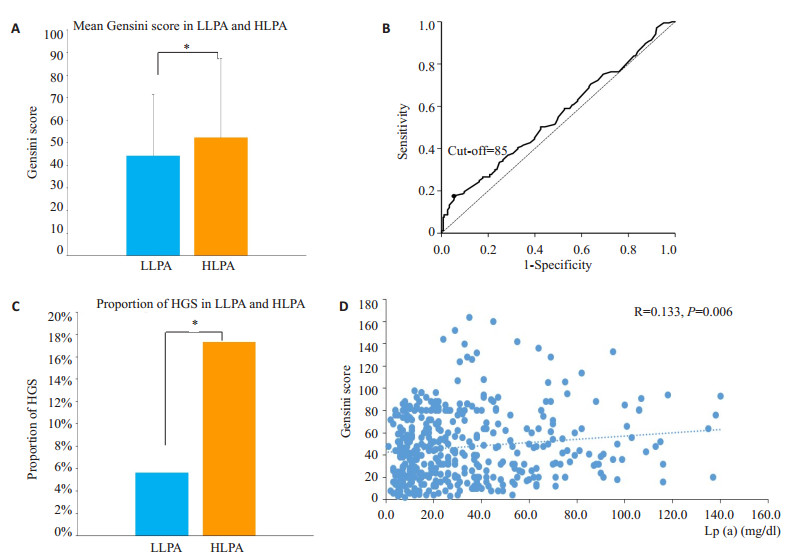

冠心病患者中高Lp(a)组和低Lp(a)组分别有173例和266例,两者的Gensini评分分别为52.35±34.58和44.26±26.98(P=0.010,图 1A)。现通过ROC曲线进一步明确Lp(a)对冠脉狭窄影响的程度,由此可得到Gensini评分的cut-off值为85(图 1B)。图 1C显示在冠心病患者中,高Lp(a)和低Lp(a)两组高Gensini评分患者的比例分别为17.3%和5.6%(P=0.026)。相关性分析提示CAD患者Gensini评分与Lp(a)存在线性关系(R=0.130, β=0.142, 95%CI: 0.040~0.244, P=0.006,图 1D)。

|

图 1 冠心病患者血清Lp(a)与Gensini评分的关系 Fig.1 Relationship between Lp(a) and Gensini score in patients with CAD. A: Mean Gensini score in LLPA and HLPA groups; B: ROC curve of Lp(a) affecting Gensini score; C: Proportion of HGS in LLPA and HLPA group; D: Relationship between Lp(a) and Gensini score. LLPA: Low lipoprotein(a); HLPA: High lipoprotein(a); HGS: High Gensini score. *P < 0.05. |

本研究是在中老年人群中探索血清Lp(a)水平与罹患CAD的风险,CAD人群中Lp(a)差异与临床稳定性及冠脉狭窄程度的相关性。根据Lp(a)水平将入组的531例患者分为高、低Lp(a)两组,回顾性分析其临床资料、血脂情况及冠脉造影结果,调整混杂因素后发现年龄、性别、LDL-C是CAD的独立危险因素。既往对Lp(a)与冠心病关系的研究结果并不统一,有研究显示对LDL-C控制达标的CAD患者Lp(a)升高与其病情进展无相关性[14],也有研究指出高Lp(a)水平的CAD患者病情更重[15]。本研究通过多因素logistic回归分析显示,调整了混杂因素后发现血清Lp(a)水平升高增加CAD风险,这与既往研究结果一致[16-17]。

冠心病的基础是动脉粥样硬化,内皮损伤和脂质沉积参与了斑块形成到管腔进行性狭窄的整个过程,进一步深入探讨脂质及脂蛋白参与动脉粥样硬化进展的机制是目前防治冠心病的方向之一[18-19]。本研究中,高、低Lp(a)两组间LDL-C没有相关性,而一项53 2359人规模的研究表明LDL-C和Lp(a)之间存在微弱的相关性[5]。进一步研究证实经多因素回归分析表明Lp(a)能独立增加CAD风险,且无论LDL-C水平高低,Lp(a)升高均增加罹患CAD的风险,这种相关性在LDL-C升高时更明显。

本研究中CAD患者Lp(a)水平升高与其临床严重程度及冠脉狭窄程度相关。既往研究表明存在高危因素拟行冠状动脉介入手术的CAD患者中有48%合并Lp(a)升高[20]。还有研究表明CAD患者发生ACS的风险可能与Lp(a)水平有关,应用Lp(a)联合LDL-C可用于评估CAD的严重程度[21]。Lp(a)在冠心病发生发展的机制研究显示:Apo(a)可以通过与β2整合蛋白结合后促进炎性细胞的粘附与迁移,炎症反应促进动脉粥样硬化的发生;同时Lp(a)中含有血小板活化因子乙酰水解酶,能够水解和抑制血小板活化因子而促进炎症反应的发生[22]。另一方面,Apo(a)与纤溶酶原存在高度的结构同源性,能竞争地抑制纤溶酶原与血小板结合,抑制纤溶过程及血栓溶解,在血栓的形成中发挥作用[23]。

但目前有关Lp(a)的观点尚未统一[24-25]。2016年ESC血脂管理指南[26]认为Lp(a)检测在普通人群中价值相对较小,但对评估未来10年心血管事件风险为高危和有CAD家族史的患者则十分重要。目前有关降Lp(a)的临床研究结局均有LDL-C的同步降低,因而通过降低Lp(a)防治CAD尚需更多的随机对照研究加以佐证。

本研究尚存在以下不足:首先,本研究为单中心回顾性队列研究,样本量较少,且入组对象为有冠脉造影指征的住院患者,其本身危险分层及出现CAD事件的风险较普通人群高,相关结论的应用需扩大样本人群证实;其次,本研究中Lp(a)的检测只局限于颗粒水平,未能进一步说明不同分型的Lp(a)对结局对影响;而且本研究未引入时间因素与CAD发病的相关风险,在论证强度上有所欠缺。

总而言之,本研究再次证明Lp(a)是CAD的独立危险因素,高Lp(a)人群患CAD风险更高,且无论LDLC处于高低水平均存在该风险;在冠心病患者中Lp(a)升高与其临床严重程度及冠脉狭窄程度有关,Lp(a)处于高水平时其Gensini评分明显增高,是狭窄程度的独立危险因素。临床工作中联合检测LDL-C和Lp(a)可以进一步完善患者相关危险分层,指导患者进行预防。

| [1] |

戴闺柱. 与血脂指南有关的若干脂质新理念[J].

中华心血管病杂志, 2015, 43(11): 930-33.

DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2015.11.002. |

| [2] |

Laschkolnig A, Kollerits B, Lamina CA, et al. Lipoprotein (a) concentrations, apolipoprotein (a) phenotypes, and peripheral arterial disease in three independent cohorts[J].

Cardiovasc Res, 2014, 103(1): 28-36.

|

| [3] |

Gencer B and F Mach. Lipoprotein (a):the perpetual supporting actor[J].

Eur Heart J, 2018, 39(27): 2597-9.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy385. |

| [4] |

Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a cardiovascular risk factor:current status[J].

Eur Heart J, 2010, 31(23): 2844-53.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq386. |

| [5] |

Varvel S, Mcconnell JP, Tsimikas S. Prevalence of elevated Lp (a) mass levels and patient thresholds in 532359 patients in the United States[J].

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2016, 36(11): 2239-45.

DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308011. |

| [6] |

Waldeyer C, Makarova N, Zeller TA, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the European population:results from the BiomarCaRE consortium[J].

Eur Heart J, 2017, 38(32): 2490-8.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx166. |

| [7] |

Zhang HW, Zhao X, Guo YL, et al. Elevated lipoprotein (a) levels are associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J].

Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2018, 28(10): 980-6.

DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.05.010. |

| [8] |

Zewinger S, Kleber ME, Tragante V, et al. Relations between lipoprotein (a) concentrations, LPA genetic variants, and the risk of mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease:a molecular and genetic association study[J].

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2017, 5(7): 534-43.

DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30096-7. |

| [9] |

Willeit P, Kiechl S, Kronenberg F, et al. Discrimination and net reclassification of cardiovascular risk with lipoprotein (a)[J].

J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014, 64(9): 851-60.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.061. |

| [10] |

中国成人血脂异常防治指南制订联合委员会. 中国成人血脂异常防治指南[J].

中华心血管病杂志, 2016, 31(10): 937-50.

|

| [11] |

Cannon CP, Brindis RG, Chaitman BR, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease[J].

Crit Pathw Cardiol, 2013, 12(2): 65-105.

DOI: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e3182846e16. |

| [12] |

Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris:executive summary:The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology[J].

Eur Heart J, 2006, 27(11): 1341-81.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001. |

| [13] |

Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease[J].

Am J Cardiol, 1983, 51(3): 606.

DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9149(83)80105-2. |

| [14] |

Puri R, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary atheroma progression rates during long-term highintensity statin therapy:Insights from Saturn[J].

Atherosclerosis, 2017, 263: 137-44.

DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.06.026. |

| [15] |

Simons LA, Simons J, Friedlander YA. LDL-cholesterol Predicts a First CHD Event in Senior Citizens, Especially So in Those With Elevated Lipoprotein (a):Dubbo Study of the Elderly[J].

Heart Lung Circ, 2018, 27(3): 386-9.

DOI: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.04.012. |

| [16] |

Rigamonti F, Carbone F, Montecucco F, et al. Serum lipoprotein (a) predicts acute coronary syndromes in patients with severe carotid stenosis[J].

Eur J Clin Invest, 2018, 48(3): e12888.

DOI: 10.1111/eci.2018.48.issue-3. |

| [17] |

Erhart G, Lamina C, Lehtimaki TA, et al. Genetic factors explain a major fraction of the 50% lower lipoprotein (a) concentrations in finns[J].

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2018, 38(5): 1230-41.

DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310865. |

| [18] |

Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in People at low risk of vascular disease:meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials[J].

Lancet, 2012, 380(9841): 581-90.

DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. |

| [19] |

Laufs U, Weingaertner O. Pathological phenotypes of LDL particles[J].

Eur Heart J, 2018, 39(27): 2574-6.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy387. |

| [20] |

Weiss MC, Berger JS, Gianos E, et al. Lipoprotein (a) screening in patients with controlled traditional risk factors undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention[J].

J Clin Lipidol, 2017, 11(5): 1177-80.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.07.005. |

| [21] |

Sun D, Zhao X, Li S, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a marker for predicting the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in untreated Chinese patients undergoing coronary angiography[J].

Biomed Environ Sci, 2018, 31(4): 253-60.

|

| [22] |

Ellis KL, Boffa MB, Sahebkar AA, et al. The Renaissance of lipoprotein (a):Brave New World for preventive cardiology?[J].

Prog Lipid Res, 2017, 68: 57-82.

DOI: 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.09.001. |

| [23] |

Gencer B, Kronenberg F, Stroes ES, et al. Lipoprotein (a):the revenant[J].

Eur Heart J, 2017, 38(20): 1553-60.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx033. |

| [24] |

Gaudet D, Watts GF, Robinson JG, et al. Effect of alirocumab on lipoprotein (a) over ≥ 1.5 years (from the phase 3 ODYSSEY program)[J].

Am J Cardiol, 2017, 119(1): 40-6.

DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.09.010. |

| [25] |

Verbeek R, Hoogeveen RM, Langsted AA, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk associated with elevated lipoprotein (a) attenuates at low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in a primary prevention setting[J].

Eur Heart J, 2018, 39(27): 2589-96.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy334. |

| [26] |

Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias[J].

Eur Heart J, 2016, 37(39): 2999-3058.

DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272. |

2019, Vol. 39

2019, Vol. 39