2. 南京医科大学第三临床医学院,江苏 南京 210006;

3. 南京 医科大学附属南京医院内分泌科,江苏 南京 210012

2. The Third Clinical Medical College of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China, 210006;

3. Department of Endocrinology, The Affiliated Nanjing Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China, 210012

餐后高血糖与糖尿病慢性并发症风险密切相关[1-4],尤其是对于2型糖尿病(T2DM)患者[5-6]。因此,控制餐后高血糖是T2DM患者治疗的重要目标。尽管应用降糖药物及严格控制饮食,但餐后高血糖及血糖波动仍然是T2DM患者的主要特征[7-8]。因此,我们需要另外的治疗策略来控制餐后高血糖。

运动已成为T2DM患者治疗的重要基石[9]。既往已有多项研究[10-16]表明,餐后运动可使餐后血糖明显下降。然而,晚餐后运动对糖尿病患者餐后血糖影响的研究较少。晚餐后运动可能导致1型糖尿病(T1D)的儿童发生夜间低血糖[17-18],使T2DM患者迟发性低血糖风险增加[19]。在临床中,夜间低血糖很容易被忽视,而动态血糖监测(CGM)能够连续监测患者数天的血糖,尤其能监测到不易发现的无症状夜间低血糖。既往有研究[14]表明无严重并发症的T2DM患者晚餐后进行20 min轻中度运动,与不运动或餐前运动相比,可有效降低餐后高血糖,但该研究未使用CGM。在我国,人们习惯于晚餐后运动,本研究组前期研究通过CGM观察晚餐后运动对T2DM患者血糖谱的影响,结果显示晚餐后0.5 h进行20 min中强度运动可明显改善餐后高血糖及血糖波动,同时无低血糖发生。但是晚餐后何时运动对改善餐后高血糖更有利却未完全明确。有学者报道[20],晚餐后1.5 h进行运动与餐后1 h或0.5 h运动相比,对T2DM患者的即时降糖作用最强。而另外一项研究[21]报道,血糖达到峰值前0.5 h进行运动可以使峰值血糖降低更为显著。这两项研究均未使用CGM,而是通过每间隔0.5或1 h测一次毛细血管血糖或血清血糖来反映血糖变化,这并不能完整反映餐后血糖变化。

本研究应用CGM观察晚餐后0.5 h和晚餐后1 h这两个不同时间段进行短时中强度运动对T2DM患者的餐后血糖谱的影响有无区别。

1 对象和方法 1.1 研究对象根据WHO诊断及分型入组确诊的T2DM患者,无糖尿病急、慢性并发症,无肝肾疾病、心肺疾病及运动禁忌。排除标准为:使用外源性胰岛素、近期体质量变化大(>3 kg/6月)以及规律运动(>150 min/周)。本研究最终纳入15例(9名男性,6名女性)志愿参加研究的平时缺乏运动T2DM患者,通过饮食控制和/或口服降糖药控制血糖。所有受试者试验期间均保持药物维持不变,提供标准化糖尿病饮食。本研究方案获得南京医科大学附属南京医院医学伦理委员会的批准,且受试者均签署了知情同意书。

1.2 研究方法在入组时,收集受试者年龄、身高、体质量、血压、静息心率(HR)、既往病史和用药情况的数据。隔夜禁食至少10 h,收集所有受试者的血液样本。测量血浆葡萄糖、总胆固醇(TC)、甘油三酯(TG)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(HDL-C)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)、尿酸和肌酐水平。糖化血红蛋白HbA1c由DiaSTAT HbA1c分析仪测定。受试者均通过跑步机完成有氧运动能力测试,通过12导联心电图监测心功能。

1.2.1 研究设计将受试者随机分成两组,分别纳入晚餐后0.5 h运动组和晚餐后1 h运动组,7 d后交叉。在运动日前1 d 16:00~17:00,将CGM(美敦力)传感器置入受试者的前腹部,在运动日后1 d 08:00~09:00移除CGM。在使用CGM期间,每日使用罗氏卓越型血糖测试仪采集4次手指毛细血管血糖,分别为3餐前及睡前,由内分泌科专门护士输入来校准CGM血糖值。通过上述方法,CGM可以每5 min监测1次皮下组织间质液中葡萄糖浓度,从而用于评估血糖连续变化。为进一步分析,将持续血糖监测的时间分成不同时段,分别为:餐后2 h、餐后3 h、夜间(从凌晨00:00到次日早上06:00)以及餐后12 h(从晚上17:00到次日早上05:00)。

所有受试者在运动日前2 d不进行剧烈体力劳动和运动训练。分别在晚餐后0.5 h或1 h开始进行0.5 h中等强度运动,并要求在运动当天的其他时段禁止参加中度或重度运动。

心率监测仪被用于监测整个运动过程,使用储备心率(HRR)方法计算运动强度[22],将运动强度设定为HRR的40%。该方法是先预估最大HR,即220减去受试者的年龄,而HRR就是预估的最大HR和静息HR之间的差值,运动时心率设定为静息HR+40% HRR。受试者在跑步机上完成所有的运动,通过调整跑步机速度,将运动强度调整到设定心率。在这0.5 h运动过程中不包括3 min的热身和2 min的减速时间。受试者被要求在整个运动期间保持该运动强度。

1.2.2 药物与饮食受试者所使用的药物在整个试验过程中保持不变,服用降糖药的时间保持相同。在试验期间,提供给受试者标准化饮食,确保每天总能量摄入量为105 kJ/kg/d,其中55%的热量由碳水化合物提供、18%的热量由蛋白质提供,剩余的27 %的热量由脂肪提供。分为3等份分别在07:00、11:30和17:00提供给受试者作为早、中、晚餐。为确保两个运动日之间的饮食匹配,受试者被要求在这两天进食相同种类的食物。早餐包括纯牛奶、鸡蛋和白面馒头,午餐包括白米饭、青菜、瘦肉、青椒和豆干,晚餐包括白米饭、番茄、瘦肉、豆腐和白菜(标准餐见表 1)。

| 表 1 标准餐的食物组成 Table 1 Composition of a standard 2000-kcal meal for the participants |

将数据从CGM导出并转换成血糖值。餐后血糖曲线下面积(AUC)使用梯形法计算。高峰血糖是指晚餐后2 h或3 h内的最高血糖值。餐后血糖峰值是指餐后高峰血糖和餐前血糖之间的差值。血糖变异系数(CV)是血糖标准差(SDBG)除以平均血糖(MBG)而得到的参数,反映血糖波动情况。平均血糖波动幅度(MAGE)是计算连续峰值和最低值之间差值的算术平均数,而峰值至最低值或最低值至峰值的方向是由第一次偏移方向确定的,同时仅计算平均血糖波动值超过1 SD的偏移量[23]。

数据分析使用统计软件SPSS 17.0进行。所有数据通过Kolmogorov-Smirnov或Shapiro-Wilk检验正态分布。正态分布的变量以均数±标准差表示。两组间比较用配对t检验。两组间特定时间点血糖的比较使用重复测量方差分析。P<0.05被认为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 受试者临床特征共9名受试者使用口服降糖药,而6名受试者口服降压药治疗,8名受试者正在口服降脂药物。所有受试者均严格遵守饮食标准及运动流程,无受试者退出研究(表 2)。

| 表 2 受试者临床特征 Table 2 Participant characteristics at baseline |

受试者静息心率为72.3±3.9 b/min。以受试者运动结束前最后5 min测量的心率设为运动心率,餐后0.5 h运动组的运动心率为115 ± 4.5 b/min,对应于HRR的43.0% ± 6.0%,餐后1 h运动组的运动心率为114±3.9 b/min,对应于HRR的41.0%±5.0%,两者均符合本研究设定的40% HRR强度运动,且无统计学差异(表 3)。

| 表 3 受试者运动参数 Table 3 Exercise characteristics of the participants (b/min) |

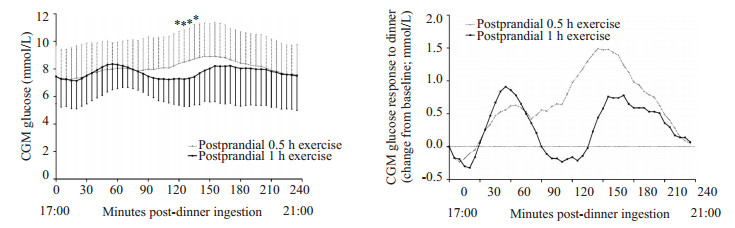

两组的餐后平均血糖变化曲线及餐后血糖与餐前血糖差值的平均值变化曲线见图 1。晚餐后0.5 h运动组与晚餐后1 h运动组的餐后2 h平均血糖(MBG)、高峰血糖、餐后血糖峰值及餐后血糖曲线下面积(AUC)均无统计学差异(表 4)。同样,两组间餐后12 h平均血糖(MBG)、CV、MAGE也无统计学差异,且均无夜间低血糖。具体参数值见表 3。但两组间晚餐后各个时间点血糖方差分析比较显示,晚餐后1 h运动组餐后120~ 135 min血糖明显低于晚餐后0.5 h运动组(P<0.05,图 1)。

|

图 1 晚餐后0.5 h运动组与晚餐后1 h运动组CGM血糖平均值及与餐前血糖差值曲线图 Figure 1 Average CGM values and average postprandial CGM glucose change from baseline in postprandial 0.5 h exercise and postprandial 1 h exercise groups during the postprandial period. Time 0 represents the time of first bite. *P < 0.05 between the two conditions. |

| 表 4 动态血糖监测指标 Table 4 Continuous glucose monitor parameters |

既往已有多项研究表明餐后运动对餐后高血糖有改善作用[10-16],但餐后何时运动对改善餐后高血糖更有利却未完全明确,国内外指南均未提及。Colberg等[14]研究显示,T2DM患者晚餐后运动与晚餐前运动或不运动相比,可以明显改善餐后高血糖。本课题组前期研究使用CGM也观察到类似结果。但这两项研究均采用了晚餐后0.5 h左右运动。而大部分研究选择餐后0.5 h[12, 15-16, 24-25]或餐后1 h[26-27]进行运动,也有一些研究选择餐后40 min[28-29]或餐后45 min运动[29]。这些研究均未提及选择这些时段进行运动的依据或原因。而本研究则观察了晚餐后0.5 h和晚餐后1 h进行短时中强度运动对无严重并发症T2DM患者餐后血糖谱的影响有何不同,结果显示两者无明显差异,均无低血糖发生,但晚餐后1 h运动对餐后2 h血糖的降糖作用更强。据我们所知,本研究是首次使用CGM观察晚餐后不同时段运动对T2DM患者血糖谱影响。

如前所述,研究[20]认为晚餐后1.5 h进行运动与餐后0.5 h或1 h进行运动相比,对T2DM患者的即时降糖作用更强。随着进餐后时间的延长,血糖达峰后逐渐下降,餐后1.5 h进行运动对餐后2 h血糖有更为明显的下降作用较易理解,但对于整个餐后血糖AUC是否有更好地改善作用未明确,,该研究每0.5 h测量外周毛细血管血糖计算出的AUC不够全面和准确。而本研究使用CGM观察餐后血糖谱的变化,每5 min测得组织间液血糖所计算AUC则更为合理。本研究中的运动时间为晚餐后,符合我国大部分人晚餐后运动习惯。而餐后1.5 h运动对于T2DM患者而言时间可能过迟,因此本研究未设置餐后1.5 h运动组,在将来的运动研究中可以考虑增设。另一项研究[21]认为血糖达峰前0.5 h进行运动更有效,但在临床应用中可能难以实施,每个T2DM患者的达峰时间各不相同,每日每餐的达峰时间可能也不恒定,因此不适合临床应用推广。

运动可能导致低血糖,包括运动后即刻发生低血糖以及运动后迟发性低血糖或夜间低血糖,夜间低血糖多发生于午后运动或夜晚运动[30]。而本研究使用CGM就可以全面地监测血糖波动,尤其是不易察觉的夜间低血糖。正如Bacchi等[19]的研究所述,晚餐前1 h有氧运动可能增加T2DM患者的迟发性低血糖的风险。然而,在本研究中无论是晚餐后0.5 h运动组还是晚餐后1 h运动组均未发现夜间低血糖。这可能与我们的所采用的短时中等强度运动有关。但从图 1餐后血糖与餐前血糖差值的变化曲线中我们可以发现,晚餐后1 h运动组受试者餐后1.5 h以后出现了比餐前血糖低的情况,尽管幅度很小,但是若运动强度再增加,时间再延长,不排除出现低血糖可能。因此,我们认为对于易出现低血糖的糖尿病患者,更推荐晚餐后0.5 h运动,同时运动强度不宜过高、时间不宜过长。

既往研究[31-32]结果表明降低餐后血糖峰值可改善炎症、内皮功能,减少颈动脉内膜中层厚度。而运动明显降低餐后高血糖,可改善T2DM患者的心血管风险。本研究结果显示,晚餐后0.5 h与晚餐后1 h短时中强度运动对T2DM患者餐后血糖峰值降低无显著差异,对运动后12 h血糖波动影响也基本一致。因此我们认为,对于无严重并发症的T2DM患者在餐后0.5 h或1 h均可进行适当的短时中强度运动,通过这种简单的运动锻炼即可获得较大的益处。

本研究还存在一些局限性。首先,研究中评估运动强度是基于心率而未使用最大氧耗量,然而在我国使用心率评估运动强度更具操作性;其次,本研究纳入的样本量偏小,但所得结果仍有临床指导意义;再次,尽管本研究组前期研究已明确晚餐后短时中强度运动明显改善T2DM患者餐后高血糖,但此次研究未设置非运动组作为对照。在后期研究中拟扩大样本量,同时设定非运动组为对照;最后,我们在研究中未测定胰岛素等激素水平来进一步探讨运动的降糖机制。

综上所述,晚餐后0.5 h与晚餐后1 h进行短时中等强度运动对无严重并发症T2DM患者餐后血糖谱影响无明显差异,均安全有效。晚餐后1 h运动可能对降低餐后2 h即时血糖更有利,但对于易出现低血糖的T2DM患者餐后0.5 h运动更安全。

| [1] |

De Vegt F, Dekker JM, Ruhe HG, et al. Hyperglycaemia is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the Hoorn population: the Hoorn Study[J].

Diabetologia, 1999, 42(8): 926-31.

DOI: 10.1007/s001250051249. |

| [2] |

Meigs JB, Nathan DM, D'agostino RB, et al. Fasting and postchallenge glycemia and cardiovascular disease risk: the framingham offspring study[J].

Diabetes Care, 2002, 25(10): 1845-50.

DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1845. |

| [3] |

Ceriello A, Hanefeld M, Leiter L, et al. Postprandial glucose regulation and diabetic complications[J].

Arch Intern Med, 2004, 164(19): 2090-5.

DOI: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2090. |

| [4] |

Ceriello A. Postprandial hyperglycemia and diabetes complications - Is it time to treat?[J].

Diabetes, 2005, 54(1): 1-7.

DOI: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.1. |

| [5] |

Cavalot F, Petrelli A, Traversa M, et al. Postprandial blood glucose is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly in women: lessons from the san luigi gonzaga diabetes study[J].

J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006, 91(3): 813-9.

DOI: 10.1210/jc.2005-1005. |

| [6] |

Cavalot F, Pagliarino A, Valle M, et al. Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: lessons from the san luigi gonzaga diabetes study[J].

Diabetes Care, 2011, 34(10): 2237-43.

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-2414. |

| [7] |

Praet SF, Manders RJ, Meex RC, et al. Glycaemic instability is an underestimated problem in Type Ⅱ diabetes[J].

Clin Sci (Lond), 2006, 111(2): 119-26.

DOI: 10.1042/CS20060041. |

| [8] |

Van Dijk JW, Manders RJ, Hartgens FA, et al. Postprandial hyperglycemia is highly prevalent throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients[J].

Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2011, 93(1): 31-7.

DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.03.021. |

| [9] |

Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: american college of sports medicine and the american diabetes association: joint position statement. exercise and type 2 diabetes[J].

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2010, 42(12): 2282-303.

DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb61c. |

| [10] |

Larsen JJ, Dela F, Kjaer M, et al. The effect of moderate exercise on postprandial glucose homeostasis in NIDDM patients[J].

Diabetologia, 1997, 40(4): 447-53.

DOI: 10.1007/s001250050699. |

| [11] |

Larsen JJ, Dela F, Madsbad S, et al. The effect of intense exercise on postprandial glucose homeostasis in type Ⅱ diabetic patients[J].

Diabetologia, 1999, 42(11): 1282-92.

DOI: 10.1007/s001250051440. |

| [12] |

Høstmark AT, Ekeland GS, Beckstrøm AC, et al. Postprandial light physical activity blunts the blood glucose increase[J].

Prev Med, 2006, 42(5): 369-71.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.10.001. |

| [13] |

Derave W, Mertens A, Muls E, et al. Effects of post-absorptive and postprandial exercise on glucoregulation in metabolic syndrome[J].

Obesity, 2007, 15(3): 704-11.

DOI: 10.1038/oby.2007.548. |

| [14] |

Colberg SR, Zarrabi L, Bennington L, et al. Postprandial walking is better for lowering the glycemic effect of dinner than pre-dinner exercise in type 2 diabetic individuals[J].

J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2009, 10(6): 394-7.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.03.015. |

| [15] |

Dipietro L, Gribok A, Stevens MS, et al. Three 15-min bouts of moderate postmeal walking significantly improves 24-h glycemic control in older People at risk for impaired glucose tolerance[J].

Diabetes Care, 2013, 36(10): 3262-8.

DOI: 10.2337/dc13-0084. |

| [16] |

Erickson ML, Little JP, Gay JL, et al. Effects of postmeal exercise on postprandial glucose excursions in people with type 2 diabetes treated with add-on hypoglycemic agents[J].

Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2017, 126: 240-7.

DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.02.015. |

| [17] |

Wilson DM, Calhoun PM, Maahs DM, et al. Factors associated with nocturnal hypoglycemia in at-risk adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes[J].

Diabetes Technol Ther, 2015, 17(6): 385-91.

DOI: 10.1089/dia.2014.0342. |

| [18] |

Tsalikian E, Mauras N, Beck RW, et al. Impact of exercise on overnight glycemic control in - Children with type 1 diabetes mellitus[J].

J Pediatr, 2005, 147(4): 528-34.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.065. |

| [19] |

Bacchi E, Negri C, Trombetta MA, et al. Differences in the acute effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in subjects with type 2 diabetes: results from the RAED2 randomized trial[J].

PLoS One, 2012, 7(12): e49937.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049937. |

| [20] |

熊艳, 梁奕铨. 餐后不同时间急性运动负荷对NIDDM患者的降糖作用[J].

中山医科大学学报, 2000, 21(5): 360.

DOI: 10.3321/j.issn:1672-3554.2000.05.012. |

| [21] |

陈璎珞, 元香南, 尹杰, 等. 不同运动因素对2型糖尿病患者早餐后糖代谢的影响[J].

中国运动医学杂志, 2007, 26(1): 29-33.

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6710.2007.01.005. |

| [22] |

Karvonen J, Vuorimaa T. Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities. Practical application[J].

Sports Med, 1988, 5(5): 303-11.

DOI: 10.2165/00007256-198805050-00002. |

| [23] |

Mo YF, Zhou J, Li M, et al. Glycemic variability is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients[J].

Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2013, 12: 15.

DOI: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-15. |

| [24] |

Hatamoto Y, Goya R, Yamada Y, et al. Effect of exercise timing on elevated postprandial glucose levels[J].

J Appl Physiol, 2017, 123(2): 278-84.

DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00608.2016. |

| [25] |

Nygaard H, Ronnestad BR, Hammarstrom DA, et al. Effects of exercise in the fasted and postprandial state on interstitial glucose in hyperglycemic individuals[J].

J Sports Sci Med, 2017, 16(2): 254-63.

|

| [26] |

Parker L, Shaw CS, Banting L, et al. Acute low-volume highintensity interval exercise and continuous moderate-intensity exercise elicit a similar improvement in 24-h glycemic control in overweight and obese adults[J].

Front Physiol, 2016, 7: 661.

|

| [27] |

Terada T, Wilson BJ, Myette-Cote E, et al. Targeting specific interstitial glycemic parameters with high-intensity interval exercise and fasted-state exercise in type 2 diabetes[J].

Metabolism, 2016, 65(5): 599-608.

DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.003. |

| [28] |

Haxhi J, Leto G, Di Palumbo AS, et al. Exercise at lunchtime: effect on glycemic control and oxidative stress in middle-aged men with type 2 diabetes[J].

Eur J Appl Physiol, 2016, 116(3): 573-82.

DOI: 10.1007/s00421-015-3317-3. |

| [29] |

Van Dijk JW, Venema M, Van Mechelen WA, et al. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise versus activities of daily living on 24-hour blood glucose homeostasis in male patients with type 2 diabetes[J].

Diabetes Care, 2013, 36(11): 3448-53.

DOI: 10.2337/dc12-2620. |

| [30] |

Nadella S, Indyk JA, Kamboj MK. Management of diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents: engaging in physical activity[J].

Transl Pediatr, 2017, 6(3): 215-24.

DOI: 10.21037/tp. |

| [31] |

Ho SS, Dhaliwal SS, Hills A, et al. Acute exercise improves postprandial cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals[J].

Atherosclerosis, 2011, 214(1): 178-84.

DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.015. |

| [32] |

Esposito K, Giugliano D, Nappo F, et al. Regression of carotid atherosclerosis by control of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus[J].

Circulation, 2004, 110(2): 214-9.

DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134501.57864.66. |

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38