2. 南方医科大学第三附属医院急危重症医学部,广东 广州 510630;

3. 南方医科大学病理生理教研室//广东省医学休克微循环重点实验室,广东 广州 510515;

4. 广州军区广州总医院重症医学科//全军热区创伤救治与组织修复重点实验室,广东 广州 510010

2. Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Third Affiliated Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510630, China;

3. Department of Pathophysiology, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Shock and Microcirculation Research, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

4. Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Guangzhou General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Key Laboratory of Tropical Zone Trauma Care and Tissue Repair of PLA, Guangzhou 510010, China

在热损伤病理过程中,血管内皮细胞(VEC)是最早出现形态和功能变化的细胞之一,其损伤可导致微循环障碍,启动弥漫性血管内凝血(DIC),参与全身炎症反应综合征(SIRS),最终促使机体发展为多器官功能障碍[1-2]。我们课题组前期研究已发现热打击可诱导HUVEC细胞广泛凋亡,其机制与核外p53快速线粒体移位,并继而激活线粒体凋亡信号有关[3-4]。除了作为一个重要的促凋亡转录因子[5-8],p53也是细胞自噬的重要调节因子[9-12],已有研究证实核外p53同时具有抑制自噬和诱导线粒体损伤、促进细胞凋亡的双重作用,这两种作用可能是诱导细胞死亡时的一致效应[13]。目前对于细胞热损伤过程中核外p53、细胞自噬及细胞凋亡三者之间的关系,国内外尚无研究报道。本研究旨在通过观察热打击原代分离的主动脉内皮细胞(MAEC)后核外p53与细胞自噬和凋亡之间的关系,阐明热打击后细胞死亡模式及其信号转导机制,探讨重症中暑所致血管内皮损害的发病机制。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要仪器与试剂二氧化碳孵箱(Heraeus);倒置相差显微镜(德国Leica);荧光显微镜(德国Leica);流式细胞仪为美国BD公司产品;酶标光度计为美国BIO-RAD产品;贝克曼GS-15R高速冷冻离心机。DMEM高糖培养基、胎牛血清(FBS)、胰酶、双抗均(Gibco);Ⅱ型胶原酶(Worthington);v WF一抗(Abcam, ab6994);α-actin一抗(Abcam, ab5694);辣根过氧化酶标记的anti-rabbit二抗(A cam, ab6721);DAB显色试剂盒(迈新生物技术DAB-0031/ 1031);Annexin V-FITC/PI凋亡检测试剂盒(Invitrogen);CCK-8细胞计数试剂盒(碧云天);线粒体膜电位检测试剂盒(JC-1,碧云天);LC3-ǁ抗体(abcam, ab63817),p53多克隆抗体(武汉博士德生物技术有限公司),Mitotracker(Invitrogen),FITC绿光标记二抗(Santa Cruz);Pifithrin-a(PFT, CalbiochemMerk),3-MA(Sigma, M9281),肝素钠(海普天);化学发光剂ECL(Amersham)。

1.2 热打击后细胞存活率测定取原代培养3~4代状态良好的MAEC细胞,按5×104/孔密度铺入96孔板,待细胞贴壁稳定后进行打击处理。对照组将细胞置于标准37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱2 h,热应激组分别置于43 ℃细胞培养箱中2 h,各组分别设置5个复孔。热打击后放回37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中复温(0、1、3、6、9 h),之后加入CCK8 10 μL/孔,操作参考说明书。用酶联免疫检测仪于450 mm处读取吸光度值,计算细胞存活率。实验分别独立重复3次。

1.3 Annexin V/PI流式细胞仪检测细胞凋亡热打击组为将细胞置于43 ℃孵育2 h,对照组37 ℃孵育2 h,热打击后继续在细胞培养箱复温(0、1、3、6、9 h)。使用Annexin V-FITC/PI试剂盒,按说明书进行操作,调整待检测细胞浓度为1×106/mL,冰PBS润洗2次,将细胞重悬于100 μL含2 μLAnnexin-V-FITC(20 μg/mL)缓冲液中轻轻混匀,避光室温放置15 min,转至流式检测管,加入400 μL PBS,每个样品临上机前加入1 μL PI(50 μg/mL),2 min后迅速检测。流式细胞仪检测激发波长Ex=488 nm;发射波长Em=530 nm。

1.4 线粒体膜电位的检测取原代培养3~4代状态良好的MAEC细胞置于43 ℃孵育2 h,对照组37 ℃孵育2 h,热打击后继续在细胞培养箱复温(0、1、3、6、9 h),用0.25%胰酶消化单层细胞,收集细胞,取约1×106细胞,重悬于0.5 mL细胞培养液中加入0.5 mL JC-1染色工作液,摇晃混匀后,置于细胞培养箱中37 ℃孵育20 min。孵育结束后,600 g 4℃离心5 min,沉淀细胞,弃上清,注意尽量不要丢弃细胞。按照1 mL JC-1染色缓冲液(5×)加入4 mL去离子水的比例,配置成适量的JC-1染色缓冲液(1×),并放置于冰浴。用JC-1染色缓冲液(1×)洗涤细胞2次:加入1 mL JC-1染色缓冲液(1×)重悬细胞,600 g 4 ℃离心5 min,沉淀细胞,弃上清;再次加入1 mL JC-1染色缓冲液(1×)重悬细胞,600 g 4 ℃离心5 min,沉淀细胞,弃上清。再用适量JC-1染色缓冲液(1×)重悬细胞后,用荧光分光光度计检测。

1.5 免疫荧光标记结合荧光显微镜观察p53线粒体移位及LC3-ǁ蛋白表达取原代培养3~4代状态良好的MAEC细胞,按5×104/孔密度接种到铺有载玻片的6孔板中,待细胞贴壁稳定后进行热打击处理。4%多聚甲醛固定,PBS漂洗;0.2%Triton X-100/PBS处理,BSA封闭,分别加入p53和LC3-ǁ一抗,4 ℃孵育过夜;次日,再分别加入FITC绿光标记二抗和Mitotracker红光标记二抗,37 ℃孵育1 h,PBS漂洗,封片剂封片,荧光显微镜下观察。

1.6 Western blot观察p53线粒体移位及LC3-ǁ蛋白表达收集对照组与热打击组的MAEC细胞,按细胞组分分离试剂盒说明书提取线粒体与细胞质。BCA法定量后,SDS聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳后,将蛋白转移至硝酸纤维素膜,5% BSA温封闭2 h,洗膜后加入LC3-ǁ抗体、p53多克隆抗体4 ℃过夜,TBST洗3遍后,加入二抗室温孵育2 h后使用化学发光剂ECL进行反应、曝光。

1.7 统计学方法采用SPSS 13.0统计软件包进行分析。计量资料,在方差齐性的基础上应用单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA),组间差异用LSD法比较,P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

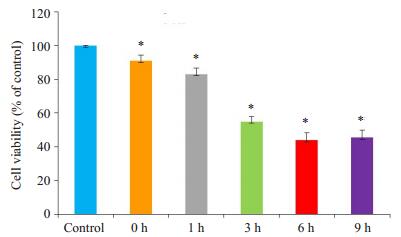

2 结果 2.1 热打击后细胞活力检测检测热打击后MAEC细胞活力,结果显示与对照组相比,热打击后细胞活力在复温0 h后呈时间依赖性下降(图 1)。

|

图 1 热打击后细胞活力检测 Figure 1 Effects of heat stress on the viability of mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) in primary culture. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

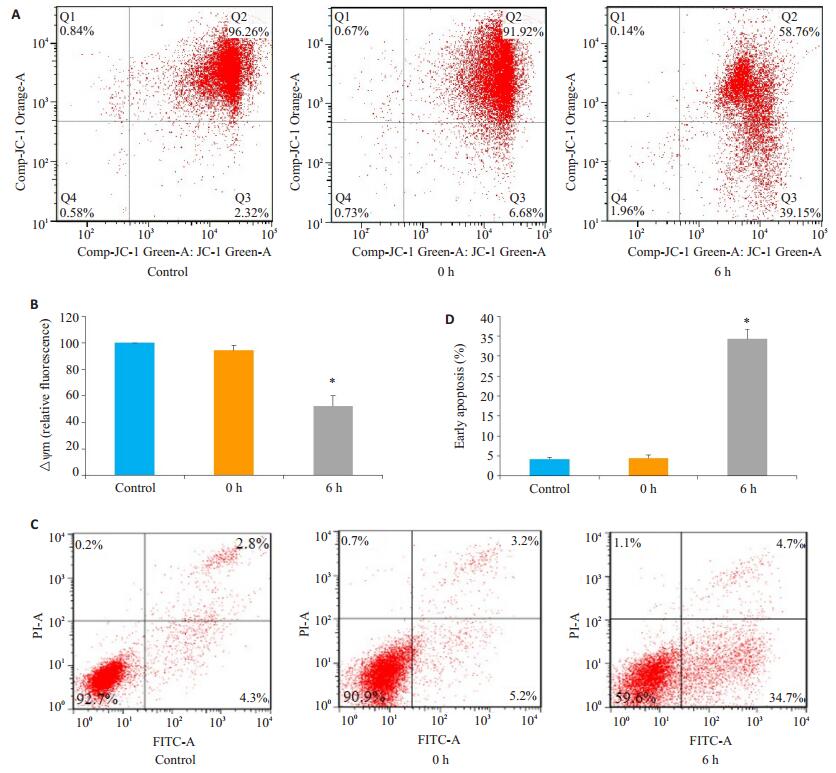

为了进一步明确热打击对MAEC细胞的影响,我们观察了细胞线粒体膜电位及细胞凋亡发生情况。结果发现热打击诱导线粒体膜电位明显下降(图 2A~B),同时细胞凋亡显著增高(图 2C~D)。这一结果表明在热打击过程中,细胞线粒体受损,并最终诱导了以凋亡为主的细胞死亡模式。

|

图 2 热打击后细胞膜电位和细胞凋亡检测 Figure 2 Changes in cell membrane potential and apoptosis after heat stress. A, B: Loss of△Ψm measured by JC-1 staining and flow cytometry; C, D: Apoptotic rate of MAECs determined by AnnexinV-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry. *P < 0.05 vs control group (37 ℃). |

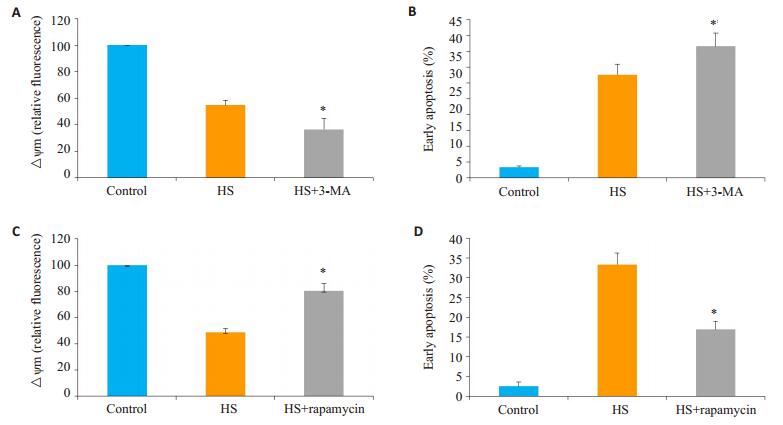

为了明确在热打击中,细胞自噬在线粒体损伤及细胞凋亡的作用,我们分别使用了细胞自噬抑制剂3-MA和自噬诱导剂rapamycin预处理细胞,43 ℃热打击细胞2 h后复温6 h,观察线粒体膜电位和细胞凋亡情况。结果显示自噬抑制剂3-MA进一步促进了热打击诱导的线粒体膜电位下降和细胞凋亡(图 3A~B);而自噬诱导剂rapamycin可明显逆转由热打击诱导的细胞线粒体膜电位下降和细胞凋亡(图 3C~D)。这一结果提示自噬在热打击诱导血管内皮损伤中起重要作用。

|

图 3 3-MA和rapamycin对热打击细胞线粒体膜电位和细胞凋亡的影响 Figure 3 Effects of autophagy inhibition and enhancement on mitochondrial damage and cell apoptosis induced by heat stress. A: flow cytometry and JC-1 measure the effect of 3-MA on △Ψm. B: The effect of 3-MA on apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry using AnnexinV- FITC/PI staining. C: flow cytometry and JC-1 measure the effect of rapamycin on △Ψm. D: The effect of rapamycin on apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry using AnnexinV-FITC/PI staining. *P < 0.05 compared with HS group. |

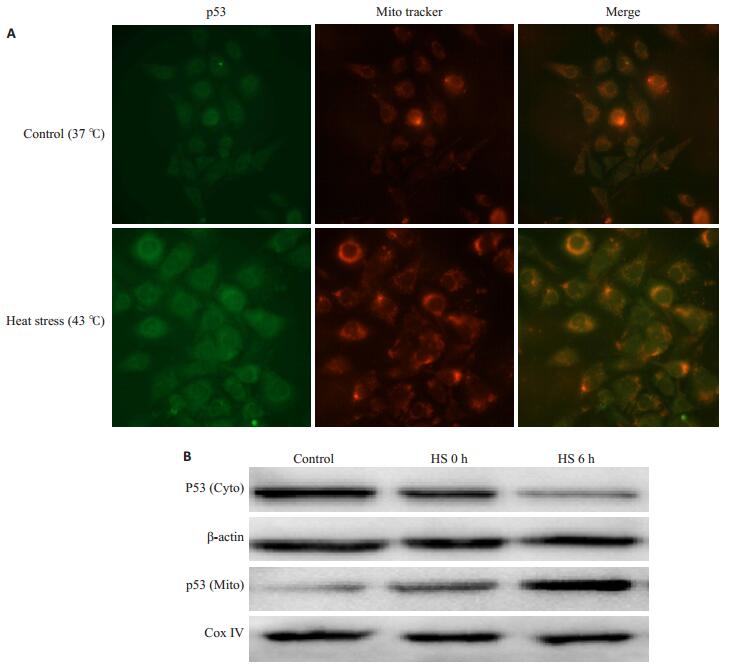

前期研究已证实在热打击HUVEC细胞模型中,p53线粒体移位是细胞凋亡的关键启动信号。为了验证这一信号在原代MAEC细胞中的作用,我们通过细胞免疫荧光染色方法分析了43 ℃热打击与37 ℃对照组p53的亚细胞定位,Mitotracker标记线粒体,红色为Mitotracker标记的线粒体,绿色为P53免疫荧光染色,如果p53移位到线粒体,在荧光显微镜下可以观察到红色和绿色重叠变为橙色。结果显示,在37 ℃对照组我们可以分别观察到Mitotracker标记红色荧光和p53标记绿色荧光,Merge后没有发现重叠的橙色荧光,而热打击2 h后复温6 h红色和绿色重叠变为橙色(图 4A),表明P53与Mitotracker发生了共定位,即热打击诱导了p53线粒体转位。进一步通过western blot检测p53的亚细胞定位发现,与37 ℃对照组比较,热打击后随着复温时间(0 h、6 h)延长,胞浆p53表达逐渐减弱,而线粒体p53表达逐渐增强(图 4B)。这一结果进一步确认了热打击后,细胞核外p53发生了线粒体移位。

|

图 4 热打击诱导p53线粒体移位 Figure 4 Heat stress induces translocation of p53 from nucleus to mitochondria. A: Confocal laser scanning microscopy localizing p53 in the mitochondria in cells with heat stress. The cells were stained with antip53 antibody (green) and MitoTracker (red); B: Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions of p53 detected by Western blotting. |

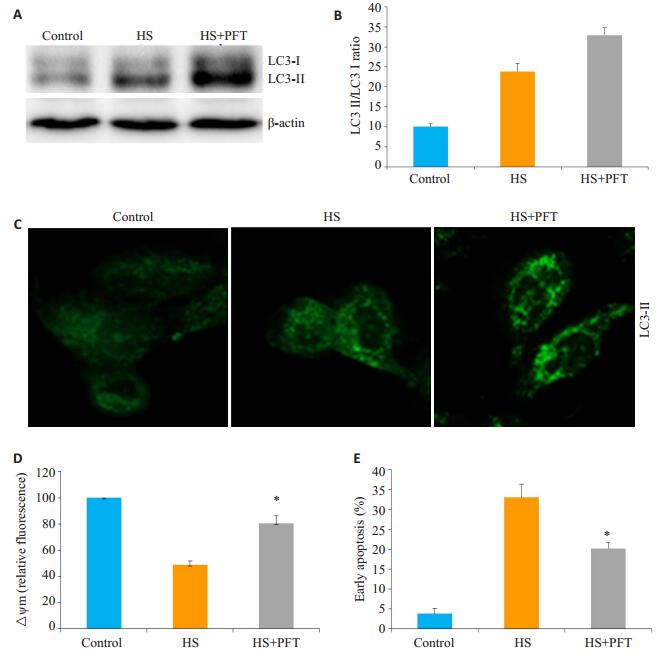

前期研究已证实p53抑制剂可明显改善热打击诱导细胞线粒体损伤及细胞凋亡,本研究在原代细胞中,p53抑制剂明显诱导了细胞自噬、同时减轻了热打击诱导细胞线粒体损伤。为了进一步分析核外P53是否介导了细胞自噬抑制,继而激活线粒体凋亡信号, 我们使用PFT(已有研究证实PFT可有效消除核外p53对自噬的抑制作用,并且对核内p53调控自噬作用无明显影响)预处理细胞1.5 h,热打击细胞2 h后复温6 h。观察PFT对热打击诱导细胞自噬及细胞线粒体损伤的影响。结果显示,PFT明显促进了自噬相关蛋白LC3-ǁ的表达(图 5A~C),同时也也明显抑制了热打击诱导的细胞线粒体膜电位的降低和细胞凋亡(图 5D~E)。这一结果提示核外p53介导了细胞自噬抑制,继而激活线粒体凋亡信号。

|

图 5 p53抑制剂PFT对热打击细胞自噬及凋亡的影响 Figure 5 Effect of p53 inhibitor PFT on heat stress-induced autophagy and mitochondrial apoptosis signaling. A, B: Western blot analysis of the effect of PFT on LC3-Ⅱ in MAEC cells with heat stress; C: Confocal laser scanning microscopy for observing the effect of PFT on LC3-Ⅱ in cells after heat stress; D: Flow cytometry and JC-1 staining for assessing the effect of PFT on △Ψm; E: Effect of PFT on apoptotic rate of MAECs determined by AnnexinV-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometry. *P < 0.05 vs heat stress group. |

人体长时间在高温环境下可出现一系列不良应激反应,严重时可导致器官功能损害,甚至诱发重症中暑的发生,直接威胁人们的生命[14-15]。已有研究表明,在高热刺激的直接或间接作用下,早期血管内皮细胞即可出现形态和功能改变,其损伤也被认为是重症中暑重要的发病机制之一[1, 6]。我们前期在HUVEC细胞热打击模型研究中发现,高热打击(43 ℃)诱导细胞广泛凋亡,在这一过程中核外p53快速线粒体移位,继而激活线粒体凋亡信号起关键作用[3-4]。但是对于核外p53如何介导线粒体损伤并最终激活内源性凋亡信号目前仍不明确。本项目在前期研究基础上,利用原代MAEC细胞热打击模型验证了热打击诱导细胞线粒体损伤和细胞凋亡,更为重要的是发现核外p53介导的细胞自噬抑制是这一过程的重要机制。

正常的自噬过程对于维持细胞内环境的稳定性及细胞生命活动的顺利进行十分重要,细胞自噬不足时常引起损伤的细胞器及变性蛋白等不能被及时清除,内环境的稳定状态被破坏,但过度的自噬也会导致自噬应激,诱导细胞结构受损(如造成线粒体及内质网等功能障碍等)[17-18]。研究表明,自噬和凋亡既互相区别,又不可分割,两者通常共存于同一细胞,可能有共同的调节机制[19-24]。目前普遍认为两者可能在以下几个存在交互效应:自噬促进凋亡、自噬与凋亡相互拮抗、自噬与凋亡协同促进细胞死亡[21, 25-26]。本实验发现在热打击诱导MAEC细胞损伤中,自噬抑制剂3-MA [27-28]进一步增强了热打击对细胞的损伤效应,细胞表现为线粒体损伤加重及细胞凋亡率增加。而自噬诱导剂rapamycin [29]可逆转上述效应。这一结果验证了文献所报道的自噬和凋亡之间密不可分的联系,推测热损伤中,细胞自噬抑制,导致损伤的细胞器及变性蛋白等不能被及时清除,继而促进细胞线粒体损伤及细胞凋亡。

当然,细胞在应对不同的外界刺激需要精确的自噬或凋亡信号调节机制。我们前期研究已证实,核外p53线粒体移位并诱导线粒体损伤,最终激活线粒体凋亡信号是热打击诱导内皮细胞广泛凋亡的重要分子机制[4]。本项目研究中,我们利用原代MAEC热打击细胞模型验证了这一分子机制。研究表明,p53在自噬调控中发挥复杂而又重要的作用,从亚细胞定位层面来看,核外p53抑制细胞自噬,核内p53促进细胞自噬[11-13, 30]。本项目研究发现p53线粒体移位是热打击后MAEC细胞自噬的主要调控机制,抑制p53线粒体移位可明显促进细胞自噬,并减轻线粒体损伤及细胞凋亡发生率。因此,热打击不仅诱导了核外p53的促凋亡功能,也启动了其自噬抑制功能,并且自噬受抑可能是热打击激活线粒体凋亡信号,继而介导细胞早期广泛凋亡的关键。

尽管我们的初步研究已发现热打击诱导核外p53抑制自噬、激活线粒体凋亡途径这一信号通路在热打击诱导血管内皮细胞凋亡中的重要作用,但到目前为止对这一通路的具体机制仍不明确,尤其是对于核外p53如何介导细胞自噬仍需深入探索。

| [1] |

Wu C, Guo S, Niu Y, et al. Heat-shock protein 60 of Porphyromonas gingivalis May induce dysfunction of human umbilical endothelial cells via regulation of endothelial-nitric oxide synthase and vascular endothelial-cadherin[J].

Biomed Rep, 2016, 5(2): 243-7.

DOI: 10.3892/br.2016.693. |

| [2] |

Leon LR, Helwig BG. Heat stroke: Role of the systemic inflammatory response[J].

J Appl Physiol, 2010, 109(6): 1980-8.

DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00301.2010. |

| [3] |

Gu ZT, Wang H, Li L, et al. Heat stress induces apoptosis through transcription-independent p53-mediated mitochondrial pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cell[J].

Sci Rep, 2014, 4: 4469.

|

| [4] |

Gu ZT, Li L, Wu F, et al. Heat stress induced apoptosis is triggered by transcription-independent p53, Ca(2+) dyshomeostasis and the subsequent Bax mitochondrial translocation[J].

Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 11497.

DOI: 10.1038/srep11497. |

| [5] |

Levine AJ. Reviewing the future of the P53 field[J].

Cell Death Differ, 2018, 25(1): 1-2.

DOI: 10.1038/cdd.2017.181. |

| [6] |

Lane D, Levine A. p53 research: the past thirty years and the next thirty years[J].

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2010, 2(12): a000893.

|

| [7] |

Fridman JS, Lowe SW. Control of apoptosis by p53[J].

Oncogene, 2003, 22(56): 9030-40.

DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207116. |

| [8] |

Haupt S, Berger M, Goldberg Z, et al. Apoptosis-the p53 network[J].

J Cell Sci, 2003, 116(Pt 20): 4077-85.

|

| [9] |

Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53[J].

Nat Cell Biol, 2008, 10(6): 676-87.

DOI: 10.1038/ncb1730. |

| [10] |

Morselli E, Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, et al. Mutant p53 protein localized in the cytoplasm inhibits autophagy[J].

Cell Cycle, 2008, 7(19): 3056-61.

DOI: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6751. |

| [11] |

Tasdemir E, Chiara Maiuri M, Morselli E, et al. A dual role of p53 in the control of autophagy[J].

Autophagy, 2008, 4(6): 810-4.

DOI: 10.4161/auto.6486. |

| [12] |

Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, et al. Autophagy regulation by p53[J].

Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2010, 22(2): 181-5.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.001. |

| [13] |

Ranjan A, Iwakuma T. Non-Canonical cell death induced by p53[J].

Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17(12): pii: E2068.

DOI: 10.3390/ijms17122068. |

| [14] |

Leon LR, Bouchama A. Heat stroke[J].

Compr Physiol, 2015, 5(2): 611-47.

|

| [15] |

Howe AS, Boden BP. Heat-related illness in athletes[J].

Am J Sports Med, 2007, 35(8): 1384-95.

DOI: 10.1177/0363546507305013. |

| [16] |

Plumier JC, Robertson HA, Currie RW. Differential accumulation of mRNA for immediate early genes and heat shock genes in heart after ischaemic injury[J].

J Mol Cell Cardiol, 1996, 28(6): 1251-60.

DOI: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0115. |

| [17] |

Cai Y, Arikkath J, Yang L, et al. Interplay of endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in neurodegenerative disorders[J].

Autophagy, 2016, 12(2): 225-44.

DOI: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1121360. |

| [18] |

Jiang XS, Chen XM, Wan JM, et al. Autophagy protects against palmitic acid-induced apoptosis in podocytes in vitro[J].

Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 42764.

DOI: 10.1038/srep42764. |

| [19] |

Fernández A, Ordóñez R, Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin and endoplasmic reticulum stress: relation to autophagy and apoptosis[J].

J Pineal Res, 2015, 59(3): 292-307.

DOI: 10.1111/jpi.12264. |

| [20] |

Wu H, Che X, Zheng Q, et al. Caspases: a molecular Switch node in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis[J].

Int J Biol Sci, 2014, 10(9): 1072-83.

DOI: 10.7150/ijbs.9719. |

| [21] |

Booth LA, Tavallai S, Hamed HA, et al. The role of cell signalling in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis[J].

Cell Signal, 2014, 26(3): 549-55.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.028. |

| [22] |

Gump JM, Thorburn A. Autophagy and apoptosis: what is the connection[J].

Trends Cell Biol, 2011, 21(7): 387-92.

DOI: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.03.007. |

| [23] |

Abedin MJ, Wang D, Mcdonnell MA, et al. Autophagy delays apoptotic death in breast cancer cells following DNA damage[J].

Cell Death Differ, 2007, 14(3): 500-10.

DOI: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402039. |

| [24] |

Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma[J].

J Clin Invest, 2007, 117(2): 326-36.

DOI: 10.1172/JCI28833. |

| [25] |

Sui XB, Kong N, Ye L, et al. p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents[J].

Cancer Lett, 2014, 344(2): 174-9.

DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.019. |

| [26] |

Dai C, Ciccotosto GD, Cappai R, et al. Rapamycin confers neuroprotection against Colistin- Induced oxidative stress, mitochondria dysfunction, and apoptosis through the activation of autophagy and mTOR/Akt/CREB signaling pathways[J]. ACS Chem Neurosci, 2018, [Epub ahead of print].

|

| [27] |

Miller S, Oleksy A, Perisic O, et al. Finding a fitting shoe for Cinderella: searching for an autophagy inhibitor[J].

Autophagy, 2010, 6(6): 805-7.

DOI: 10.4161/auto.6.6.12577. |

| [28] |

Zhu S, Lin G, Song C, et al. RA and ω-3 PUFA co-treatment activates autophagy in cancer cells[J].

Oncotarget, 2017, 8(65): 109135-50.

|

| [29] |

Feldman ME, Apsel B, Uotila A, et al. Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2[J].

PLoS Biol, 2009, 7(2): e38.

|

| [30] |

Abdelalim EM, Tooyama I. The p53 inhibitor, pifithrin-α, suppresses self-renewal of embryonic stem cells[J].

Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012, 420(3): 605-10.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.041. |

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38