前列腺癌是常见的泌尿系统恶性肿瘤。晚期前列腺的治疗以雄激素剥夺治疗(ADT)为主,然而大多数患者最终都将进展为雄激素不依赖的去势抵抗型前列腺癌(CRPC)[1]。目前广泛应用于治疗转移性CRPC (mCRPC)的多西他赛等化疗药物由于耐药性的产生,治疗效果有限,而耐药产生可能与前列腺癌神经内分泌分化(NED)有关[2-4]。

神经内分泌分化(NED)是前列腺癌的常见特征,常表现为神经内分泌(NE)标志物的表达增加,包括神经元特异性烯醇化酶(NSE)、嗜铬粒蛋白A(Chr A)、突触素(SYP)等[5]。有研究表明ADT的应用可以促进前列腺癌NED[6-7],而NED常提示不良预后[8-9],并且与化疗抵抗性有关[3, 10]。因此,针对NED的机制研究对改善前列腺癌的临床治疗状况有着重要意义。

有证据表明ADT或敲除雄激素受体(AR)可以增加多种炎症免疫细胞的浸润并促进前列腺癌的侵袭和转移[11-13]。其中,肥大细胞可以通过促进血管生成、组织重塑等功能在肿瘤的进展中发挥重要作用[14]。我们之前的研究证明了肥大细胞可通过抑制AR信号通路促进前列腺癌NED[15],然而在CRPC阶段,前列腺癌的进展及转化经常不依赖于雄激素及AR信号通路,而肥大细胞是否能通过non-AR信号通路调节前列腺癌NED,目前还未有文献报道。与NED前列腺癌细胞低增殖活性的特点相一致,我们在前期实验中发现肥大细胞可以诱导前列腺癌细胞的生长抑制,同时明显上调周期蛋白依赖性激酶抑制因子p21的表达,而p21是否与NED有关目前尚未明确。因此,本研究在之前的研究基础上,拟进一步探索肥大细胞促进前列腺癌NED的相关机制,为雄激素不依赖及化疗抵抗的前列腺癌的治疗提供新的思路。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要试剂和材料LNCaP细胞系购自美国ATCC,C4-2和293T由美国西南医学中心的Jer-Tsong Hsieh教授赠送,人肥大细胞系HMC-1细胞由罗彻斯特大学医学中心眼科研究所的John Frelinger教授赠送;RPMI 1640培养基、DMEM、IMDM培养基、胎牛血清(Thermo Fisher Scientific);GAPDH(6c5)抗体(Santa Cruz),Enolase-2 (NSE)和AR抗体(Cell Signaling),p21抗体(ProteinTech);Lipofectamine 2000转染试剂(Thermo Fisher Scientific);CCK8细胞增殖毒性检测试剂盒(Dojindo);多西他赛(DTX)(Selleck)。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 细胞培养LNCaP和C4-2细胞在含有10%胎牛血清(FBS)的RPMI 1640中培养,293T细胞在含有10% FBS的DMEM中培养,人肥大细胞系HMC-1在含有10%热灭活FBS、2 nmol/L谷氨酰胺、100 U/mL青霉素和50 mg/mL链霉素的IMDM中培养。所有细胞均培养于37 ℃,含有5%二氧化碳的细胞培养箱中。孔径为0.4 μm的Transwell小室用于前列腺癌细胞与HMC-1细胞的共培养,按照前列腺癌细胞单独培养或共培养分为2组,分别标记为LNCaP、LNCaP+HMC-1,以及C4-2、C4-2+HMC-1。

1.2.2 MTT实验检测前列腺癌细胞活性为了确定HMC-1共培养对前列腺癌细胞生长活性的影响,收集LNCaP和C4-2细胞接种在96孔板中(1000细胞/100 μL培养基/孔),分为2组,分别为单独培养组及共培养组。每2 d检测细胞活性,检测方法如下:将培养基替换为MTT溶液(0.5 mg/mL),在37 ℃继续孵育1 h。除去培养基后,加入DMSO 150 µL充分溶解结晶物,测定A570 nm处的吸光度。

1.2.3 平板克隆形成实验检测前列腺癌细胞增殖能力将前列腺癌细胞接种在6孔板(500细胞/2 mL)中,培养或与HMC-1细胞共培养14 d。终止培养,细胞以4%多聚甲醛固定20 min,用0.1%结晶紫染色15 min,对含有超过50个细胞的细胞克隆进行计数。

1.2.4 CCK8实验检测多西他赛对前列腺癌细胞活性的影响将C4-2细胞或共培养的C4-2细胞接种于96孔板(5000细胞/100 μL培养基/孔),24 h后,加入不同浓度(0、2、4、6、8、10 nmol/L,其中0 nmol/L浓度为只加入溶剂无水乙醇)的多西他赛处理48 h后检测细胞活性,或加入6 nmol/L多西他赛,检测不同时间点(0、24、48、72 h)的细胞活性。使用CCK8(Dojindo)检测细胞活性:用10% CCK8代替培养基并在37 ℃继续孵育1 h,然后用酶标仪测吸光度A450 nm。

1.2.5 RNA提取、逆转录和实时定量PCR实验检测相应基因的mRNA水平使用Trizol试剂(Invitrogen)提取前列腺癌细胞总RNA,用NanoDrop测定RNA浓度及纯度。使用Superscript Ⅲ转录酶(Invitrogen)对1 μg总RNA进行逆转录。以GAPDH作内参基因,使用Sybr Green qPCR试剂进行荧光实时定量PCR以检测目的基因的mRNA表达水平。QPCR引物如下:NSE,上游引物5'-AGCCTCTACGGGCATCTATGA-3',下游引物5'-TTCTCAGTCCCATCCAACTCC-3';CHGA(Chr A),上游引物5'-TAAAGGGGATACCGAGGTGATG-3',下游引物5'-TCGGAGTGTCTCAAAACATTCC-3';SYP,上游引物5'-CTCGGCTTTGTGAAGGTGCT-3',下游引物5'-CTGAGGTCACTCTCGGTCTTG-3';P21,上游引物5'-CGATGGAACTTCGACTTTGTCA-3',下游引物5'-GCACAAGGGTACAAGACAGTG-3';GAPDH,上游引物5'-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3',下游引物5'-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3'。

1.2.6 Western blot检测相应蛋白表达水平用RIPA细胞裂解液裂解前列腺癌细胞,提取总蛋白,并且在10%~12% SDS-PAGE凝胶上电泳分离20 μg蛋白,然后电转膜至PVDF膜上(Millipore)。用含有5% BSA的TBST室温封闭1 h后,用适当稀释的特异性一抗(GAPDH、NSE、AR抗体稀释比为1: 1000,p21抗体稀释比为1: 2000)4 ℃孵育过夜。将印迹与HRP标记的二抗室温孵育1 h,并使用ECL化学发光法显像。

1.2.7 质粒转染将前列腺癌细胞接种在6孔板中。当细胞汇合达到70%时,根据使用说明书,使用Lipofectamine 2000试剂进行转染。对于沉默p21表达,用p21靶向质粒pLKO.1-sh-p21或对照质粒转染C4-2细胞,分别标记为sh-p21组、scramble组;对于过表达p21,用p21过表达质粒pCMV-p21或空载体质粒转染C4-2细胞,分别标记为p21组、vector组。转染48 h后进行RT-qPCR或Western blot实验分别检测mRNA及蛋白水平的表达情况。

1.2.8 慢病毒包装和转染使用Lipofectamine 2000转染试剂将载体质粒pLKO.1-sh-AR/对照质粒,包装质粒psPAX2和包膜质粒pMD2.G共转染293T细胞,48 h后收集富含sh-AR慢病毒或对照慢病毒的上清液,过滤并在-80 ℃保存备用。前列腺癌细胞接种在6孔板中,使24 h后细胞密度为30%~40%,每孔加入0.5 mL收集的sh-AR慢病毒或对照慢病毒上清,分别标记为sh-AR组、scramble组,24 h后换液,置培养箱中继续培养。转染48~72 h后进行RT-qPCR或Western blot实验分别检测mRNA及蛋白水平的表达情况。

1.2.9 统计学分析所有统计分析均使用SPSS 22.0进行,实验数据以均数±标准差表示,两组间的比较用独立样本t检验进行统计分析,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

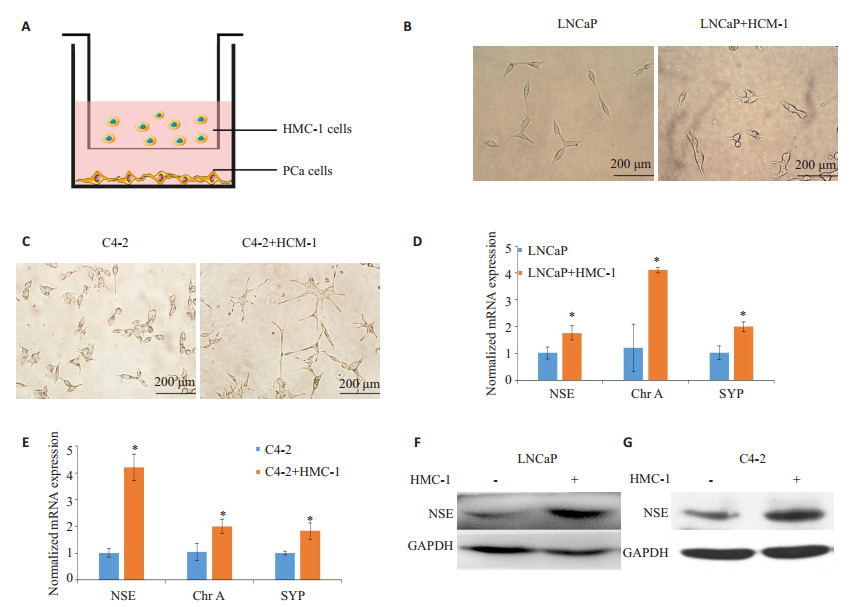

2 结果 2.1 肥大细胞促进前列腺癌细胞的神经内分泌分化在与肥大细胞(HMC-1)共培养后(图 1A),前列腺癌细胞(LNCap、C4-2)的形态从梭形变成较长的、带有树突状突触样结构的细胞形态(图 1B、C);在共培养的前列腺癌细胞中,包括NSE、ChrA、SYP在内的NE标志物的mRNA表达显著增加(P < 0.05,图 1D、E)。Western blot结果显示在共培养的LNCaP和C4-2细胞中NSE蛋白水平显著上调(图 1F、G)。

|

图 1 肥大细胞对前列腺癌细胞神经内分泌分化(NED)的作用 Figure 1 Effects of mast cells on neuroendocrine phenotypes of LNCaP and C4-2 cells. A: Schematic illustration of the co-culture system. PCa cells (LNCaP and C4-2) were plated in the lower chambers of transwells, and human mast cells (HMC-1) were plated on the upper insert chambers. PCa cells were co-cultured with or without HMC-1 cells for 48 h, and the conditioned medium (CM) was then collected. B, C: Morphological changes of LNCaP and C4-2 cells co-cultured with HMC-1 cells or not (× 200). D, E: Expressions of mRNAs of neuron-specific enolase (NSE), chromogranin A (chr A) and synaptophysin (SYP) NE markers of LNCaP and C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture determined by RT-qPCR. F, G: Total cell lysates were extracted from LNCaP and C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture, and the expressions of NSE protein were detected with Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Results are presented as Mean±SD. *P < 0.05. |

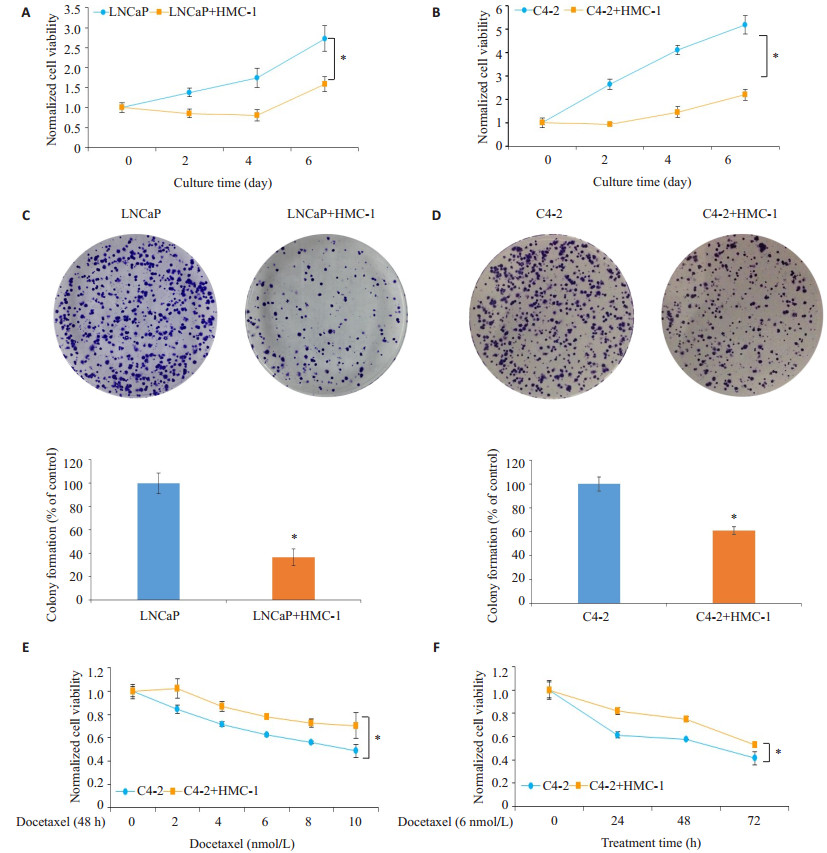

MTT实验检测细胞活性显示,共培养的LNCaP和C4-2细胞出现明显的生长抑制(图 2A和B)。克隆形成实验进一步提示,HMC-1细胞共培养使LNCaP和C4-2细胞的集落形成数量显著降低(P < 0.05,图 2C、D)。

|

图 2 肥大细胞对前列腺癌细胞的增殖及多西他赛化疗敏感性的作用 Figure 2 Effects of co-culture with mast cells on PCa cell proliferation and docetaxel sensitivity. A, B:Cell viability of LNCaP and C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture was determined by MTT assay at 0, 2, 4 and 6 days (normalized with 0 day group). C, D:Photographs and quantitative data of colony formation assay of cultured/co-cultured LNCaP and C4-2 cells. E: C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture were treated with different doses (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 nmol/L) of docetaxel for 48 h, and cell viability was determined by CCK8. All dose groups are normalized with 0 nmol/L group. F:C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture were treated with 6 nmol/L docetaxel, and the cell viability was determined by CCK8 assay at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. All time groups are normalized with 0 h group. Results were presented as Mean±SD. *P < 0.05. |

将C4-2细胞或共培养的C4-2细胞接种在96孔板中并用上述剂量的多西他赛处理48 h,CCK8结果提示,共培养组中多西他赛抑制C4-2细胞活性的效果明显减弱(P < 0.05,图 2E)。以6 nmol/L多西他赛对共培养的C4-2细胞进行不同时间的化疗时也得到了类似的结果(图 2F)。

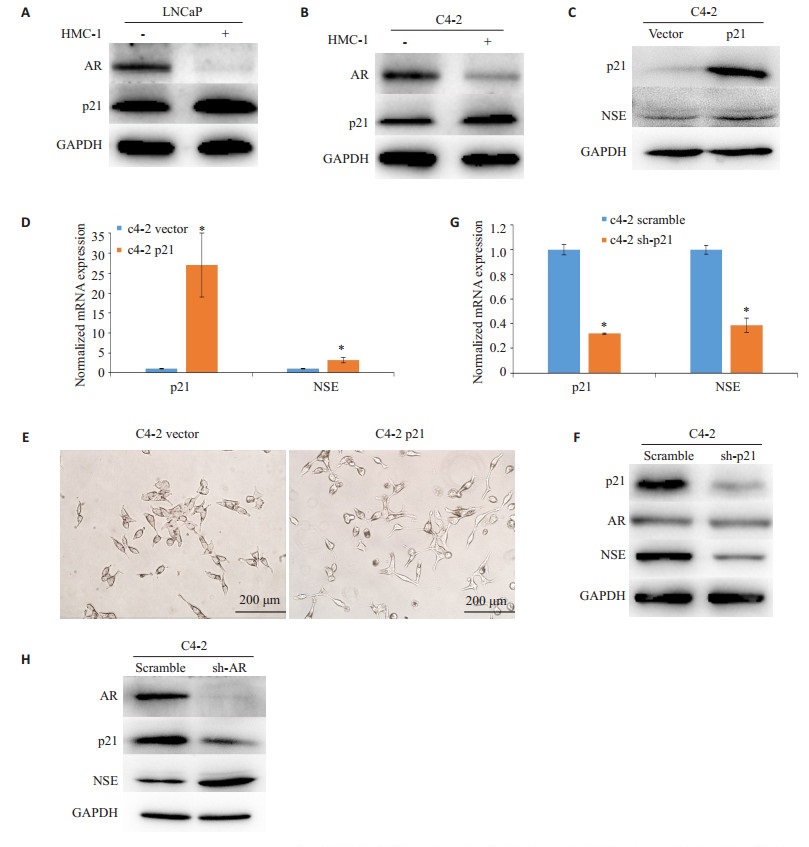

2.3 肥大细胞介导的p21过表达可以促进前列腺癌细胞NED在观察到生长抑制的同时,我们发现在共培养的前列腺癌细胞中AR的表达被明显抑制,同时p21的表达显著增加(P < 0.05,图 3A、B)。在C4-2细胞中过表达p21可导致NSE的蛋白及mRNA表达水平明显上调(P < 0.05,图 3C、D),并诱导NE样形态改变(图 3E);敲除p21则显著抑制了NSE的蛋白及mRNA表达(P < 0.05,图 3F、G)。同时,敲除p21不会影响AR的表达(图 3F),而敲除AR虽可导致NSE的表达上调,但会抑制p21的表达(图 3H、F)。

|

图 3 肥大细胞导致的p21过表达在前列腺癌细胞NED中的作用 Figure 3 Mast cells-mediated p21 overexpression promotes NED in PCa cells. A, B: Total cell lysates were extracted from LNCaP and C4-2 cells with or without HMC-1 co-culture, and the expressions of AR and p21 proteins were detected by Western blotting; C: Total cell lysates were extracted from C4-2 cells after transfection with pCMV-p21 or vector, and the expressions of p21 and NSE proteins were detected with Western blotting; D: P21 and NSE mRNAs of C4-2 cells after transfection with pCMV-p21 or vector were determined by RT-qPCR. E: Morphological changes of C4-2 cells transfected with pCMV-p21 or vector (× 200). F: Total cell lysates were extracted from C4-2 cells after transfection with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble, and the expressions of p21, AR and NSE proteins were detected with Western blotting. G: P21 and NSE mRNAs of C4-2 cells transfected with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble were determined by RT-qPCR. H: Total cell lysates were extracted from C4-2 cells transfected with sh-AR lentivirus or scramble, and the expressions of AR, p21 and NSE proteins were detected by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Results are presented as Mean±SD. *P < 0.05. |

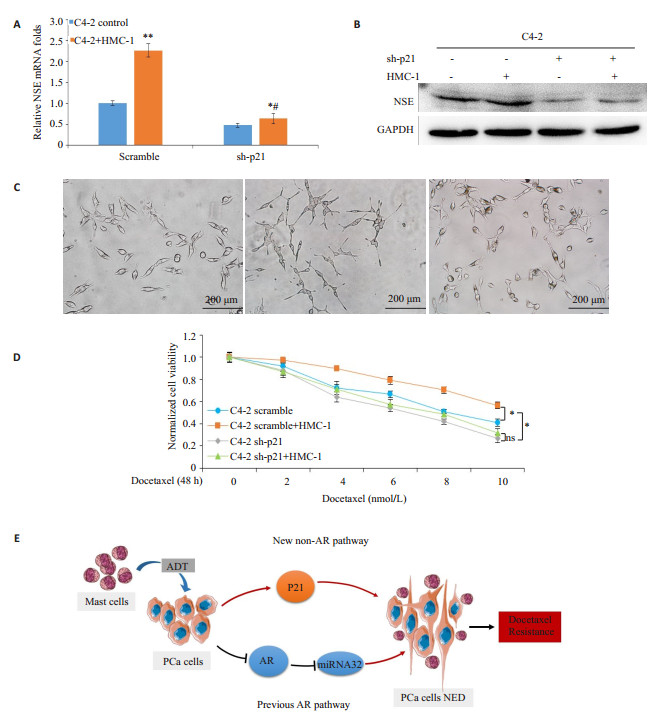

在scramble组中,共培养的C4- 2细胞中NSE mRNA表达水平显著上调(P < 0.05,图 4A)。而相比之下,在沉默p21的C4-2细胞中,HMC-1共培养上调NSE水平的幅度明显减小(P < 0.05)。敲除p21可以部分逆转由肥大细胞诱导的NSE表达上调。类似地,Western blot结果提示,p21敲除减弱了肥大细胞上调NSE蛋白表达水平的作用(图 4B)。此外,共培养导致的C4-2细胞NE形态改变也随p21的敲除而被抑制(图 4C)。与对NE表型的影响一致,敲除p21也部分逆转了肥大细胞共培养诱导的多西他赛耐药性增加(P < 0.05,图 4D)。

|

图 4 沉默p21表达可逆转肥大细胞导致的前列腺癌细胞NED和化疗抵抗性 Figure 4 Silencing 21 reverses mast cells-induced NED and docetaxel resistance in PCa cells. A: C4-2 cells transfected with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble were cultured with or without HMC-1 cells, then NSE mRNAs of each group was determined by RT-qPCR. Results are presented as Mean±SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control, #P < 0.05 compared with scramble. B: C4-2 cells transfected with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble were cultured with or without HMC-1 cells. The cell lysates were extracted and NSE proteins were detected with Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. C: Morphology change of C4-2 cells transfected with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble, with or without HMC-1 cell co-culture (× 200). D: C4-2 cells transfected with pLKO.1-sh-p21 or scramble were cultured with or without HMC-1 cells, and then treated with different doses of docetaxel for 48 h. Cell viability was detected by CCK8. Results are presented as Mean±SD. *P < 0.05. ns: No statistical significance. E: The diagram shows the AR and non-AR signaling pathways by which infiltrating mast cells promote NED in PCa. |

NED被认为参与了去势抵抗型前列腺癌CRPC的发生及进展,并与化疗等治疗的抵抗发生相关[4],但NED的发生机制还不十分清楚,尤其在肿瘤出现雄激素抵抗后是如何产生的。在本研究中我们在体外模拟前列腺癌肥大细胞浸润,发现肥大细胞介导的p21表达上调可以增加前列腺癌的NE表型,揭示了一个新的调控机制——p21调控NED,并且是不依赖雄激素受体AR而存在。

肿瘤微环境的改变对肿瘤生物学行为的影响已有广泛的研究。浸润的肥大细胞可以通过分泌促进血管生成、肿瘤生长、侵袭和调节免疫的刺激物如FGF-2,VEGF,MMP9和IL-6等发挥促进肿瘤进展的作用[16]。我们之前的研究表明,ADT导致的肥大细胞浸润可以通过抑制AR信号通路并上调miRNA32表达来促进前列腺癌NED[15],阐明了肥大细胞依赖于AR信号通路调控前列腺癌NED的部分机制。然而,在雄激素非依赖的CRPC中,肿瘤的细胞活动常不依赖于AR信号通路[17],同时,发展到去势抵抗阶段的前列腺癌往往存在更明显的NED[5],因此,在CRPC中可能存在着重要的non-AR信号通路调控NED。在本研究中,与之前的研究结果一致,肥大细胞共培养确实可以增加NE表型、促进NED而增加前列腺癌恶性特质,同时我们还发现调控细胞周期进程的一个关键蛋白p21的表达明显上调。最近有研究发现mTOR的激活可以诱导NED,同时出现的生长抑制可能与干扰素调节因子1的表达增加有关,但诱导NED的机制未能明确[18]。本研究发现肥大细胞也能够抑制前列腺癌细胞的增殖同时上调p21的表达;我们发现p21可以正向调节NED,并且该信号通路不受AR调控,作为一个新的non-AR信号通路调节前列腺癌NED,这可能为靶向阻断包括CRPC在内的前列腺癌的NED提供新的思路。另外,由于ADT可以增加肥大细胞浸润而诱导NED,通过抑制p21信号通路来阻断NED,可能有助于减少ADT在前列腺癌治疗过程中的负面作用并延缓去势抵抗的出现。

有几项临床研究表明,包括多西他赛在内的细胞毒性化疗药物对具有NE特征的前列腺癌的治疗效果不佳[19-21]。另外一些研究也将NED与化疗耐药通过多种机制联系起来[3, 10, 22]。NE细胞通常表现出低增殖活性,这个特征赋予了NED前列腺癌细胞对细胞毒性化疗药物更强的抵抗性,因为这些药物主要杀伤周期进程中的细胞[4]。此外,有研究提示,具有NE特征的前列腺癌细胞呈现出较强的抗凋亡能力[23],这可能与抗凋亡蛋白例如survivin[24-26]的表达增加有关,并且NE细胞的肿瘤干细胞样特性也可以造成化疗耐药[27-28]。事实上,我们观察到被肥大细胞共培养诱导出现NED的前列腺癌细胞,在多西他赛化疗时细胞的存活率较高,呈现出对多西他赛化疗较强的抵抗性。敲除p21部分逆转了肥大细胞诱导的NED,同时也减轻了前列腺癌细胞的多西他赛化疗抵抗性。因此,我们的研究结果支持了NED与前列腺癌化疗抵抗性之间的相关性,并且通过揭示肥大细胞部分通过p21促进NED的信号通路,我们提供了针对NED相关的肿瘤进展和改善前列腺癌多西他赛抵抗性的潜在治疗方法。

综上所述,本研究发现了肥大细胞可以部分通过上调p21表达促进前列腺癌神经内分泌分化及增加前列腺癌细胞对多西他赛化疗抵抗性,这一新的non-AR信号通路为神经内分泌分化的发生机制作出了进一步的阐释并为改善前列腺癌的治疗抵抗性提供新的思路。后续工作还需进一步探索p21调控神经内分泌分化的具体分子机制,为有效阻断该信号通路提供分子靶点。

| [1] |

Yap TA, Smith AD, Ferraldeschi RA, et al. Drug discovery in advanced prostate cancer: translating biology into therapy[J].

Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2016, 15(10): 699-718.

DOI: 10.1038/nrd.2016.120. |

| [2] |

Oudard S, Fizazi K, Sengelov L, et al. Cabazitaxel versus docetaxel as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomized phase Ⅲ Trial-FIRSTANA[J].

J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(28): 3189.

DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1068. |

| [3] |

Terry S, Maille P, Baaddi H, et al. Cross modulation between the androgen receptor axis and protocadherin-PC in mediating neuroendocrine transdifferentiation and therapeutic resistance of prostate cancer[J].

Neoplasia, 2013, 15(7): 761.

DOI: 10.1593/neo.122070. |

| [4] |

Conteduca V, Aieta M, Amadori D, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer: current and emerging therapy strategies[J].

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2014, 92(1): 11-24.

DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.05.008. |

| [5] |

Sainio M, Visakorpi T, Tolonen T, et al. Expression of neuroendocrine differentiation markers in lethal metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer[J].

Pathol Res Pract, 2018, 214(6): 848-856.

DOI: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.04.015. |

| [6] |

Bishop JL, Thaper D, Vahid S, et al. The master neural transcription factor BRN2 is an androgen receptor-suppressed driver of neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer[J].

Cancer Discov, 2017, 7(1): 54-71.

DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1263. |

| [7] |

Wang C, Peng G, Huang H, et al. Blocking the feedback loop between neuroendocrine differentiation and macrophages improves the therapeutic effects of enzalutamide (MDV3100) on prostate cancer[J].

Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(3): 708-23.

DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2446. |

| [8] |

Heck MM, Thaler MA, Schmid SC, et al. Chromogranin a and neurone-specific enolase serum levels as predictors of treatment outcome in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer undergoing abiraterone therapy[J].

BJU Int, 2017, 119(1): 30-7.

DOI: 10.1111/bju.2017.119.issue-1. |

| [9] |

Wang HT, Yao YH, Li BG, et al. Neuroendocrine prostate Cancer (NEPC) progressing from conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma: factors associated with time to development of NEPC and survival from NEPC diagnosis-a systematic review and pooled analysis[J].

J Clin Oncol, 2014, 32(30): 3383-90.

DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3553. |

| [10] |

Dasilva JO, Amorino GP, Casarez EV, et al. Neuroendocrinederived peptides promote prostate cancer cell survival through activation of IGF-1R signaling[J].

Prostate, 2013, 73(8): 801-12.

DOI: 10.1002/pros.v73.8. |

| [11] |

Izumi K, Fang LY, Mizokami A, et al. Targeting the androgen receptor with siRNA promotes prostate cancer metastasis through enhanced macrophage recruitment via CCL2/CCR2-induced STAT3 activation[J].

EMBO Mol Med, 2013, 5(9): 1383-401.

DOI: 10.1002/emmm.201202367. |

| [12] |

Lin TH, Izumi K, Lee SO, et al. Anti-androgen receptor ASC-J9 versus anti-androgens MDV3100 (Enzalutamide) or casodex (Bicalutamide) leads to opposite effects on prostate cancer metastasis via differential modulation of macrophage infiltration and STAT3-CCL2 signaling[J].

Cell Death Dis, 2013, 4: e764.

DOI: 10.1038/cddis.2013.270. |

| [13] |

Li L, Dang Q, Xie HJ, et al. Infiltrating mast cells enhance prostate cancer invasion via altering LncRNA-HOTAIR/PRC2-androgen receptor (AR)-MMP9 signals and increased stem/progenitor cell population[J].

Oncotarget, 2015, 6(16): 14179-90.

|

| [14] |

Albini A, Bruno A, Noonan DM, et al. Contribution to tumor angiogenesis from innate immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: implications for immunotherapy[J].

Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 527.

DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00527. |

| [15] |

Dang Q, Li L, Xie HJ, et al. Anti-androgen enzalutamide enhances prostate cancer neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation via altering the infiltrated mast cells -> androgen receptor (AR) -> miRNA32 signals[J].

Mol Oncol, 2015, 9(7): 1241-51.

DOI: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.010. |

| [16] |

Sfanos KS, Hempel H, De Marzo AM. The role of inflammation in prostate cancer[J].

Adv Exp Med Biol, 2014, 816: 153-81.

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8. |

| [17] |

Bluemn EG, Coleman IM, Lucas JM, et al. Androgen receptor Pathway-Independent prostate cancer is sustained through FGF signaling[J].

Cancer Cell, 2017, 32(4): 474.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.09.003. |

| [18] |

Kanayama M, Hayano T, Koebis M, et al. Hyperactive mTOR induces neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer cell with concurrent up-regulation of IRF1[J].

Prostate, 2017, 77(15): 1489-98.

DOI: 10.1002/pros.v77.15. |

| [19] |

Cindolo L, Cantile M, Vacherot F, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation prostate cancer: from lab to bedside[J].

Urol Int, 2007, 79(4): 287-96.

DOI: 10.1159/000109711. |

| [20] |

Culine S, El Demery M, Lamy P, et al. Docetaxel and cisplatin in patients with metastatic androgen Independent prostate cancer and circulating neuroendocrine markers[J].

J Urol, 2007, 178(3, 1): 844-8.

|

| [21] |

Flechon A, Pouessel D, Ferlay C, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of carboplatin and etoposide in patients with anaplastic progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with or without neuroendocrine differentiation: results of the French GenitoUrinary Tumor Group (GETUG) P01 trial[J].

Ann Oncol, 2011, 22(11): 2476-81.

DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdr004. |

| [22] |

Li Y, Chen HQ, Chen MF, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation is involved in chemoresistance induced by EGF in prostate cancer cells[J].

Life Sci, 2009, 84(25/26): 882-7.

|

| [23] |

Fixemer T, Remberger K, Bonkhoff H. Apoptosis resistance of neuroendocrine phenotypes in prostatic adenocarcinoma[J].

Prostate, 2002, 53(2): 118-23.

DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0045. |

| [24] |

Xing NZ, Qian JQ, Bostwick D, et al. Neuroendocrine cells in human prostate over-express the anti-apoptosis protein survivin[J].

Prostate, 2001, 48(1): 7-15.

DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0045. |

| [25] |

Gong JY, Lee JG, Akio H, et al. Attenuation of apoptosis by chromogranin A-induced akt and survivin pathways in prostate cancer cells[J].

Endocrinology, 2007, 148(9): 4489-99.

DOI: 10.1210/en.2006-1748. |

| [26] |

Morrison DJ, Hogan LE, Condos G, et al. Endogenous knockdown of survivin improves chemotherapeutic response in ALL models[J].

Leukemia, 2012, 26(2): 271-9.

DOI: 10.1038/leu.2011.199. |

| [27] |

Palapattu GS, Wu C, Silvers CR, et al. Selective expression of CD44, a putative prostate cancer stem cell marker, in neuroendocrine tumor cells of human prostate cancer[J].

Prostate, 2009, 69(7): 787-98.

DOI: 10.1002/pros.v69:7. |

| [28] |

Hao J, Madigan MC, Khatri A, et al. In vitro and in vivo prostate cancer metastasis and chemoresistance can be modulated by expression of either CD44 or CD147[J].

PLoS One, 2012, 7(8): e40716.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040716. |

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38