2. 广州市花都区人民医院骨科,广东 广州 510800;

3. 南方医院医科大学南方医院创伤骨科,广东 广州 510515

2. Department of Orthopedics, Huadu District People's Hospital, Guangzhou 510800, China;

3. Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

神经肽Y(NPY)对骨发育、骨生理和骨代谢有直接调控作用[1],其受体Y1,Y2与成骨细胞的分化、增殖等生物学效应密切相关[2-3]。在中枢神经系统,NPY是通过下丘脑中的Y2受体完成骨代谢调控,在外周神经系统,通过靶细胞如骨髓间充质干细胞(BMSCs)、成骨细胞等细胞膜上的Y1受体调控骨代谢[4-6]。但在Y1受体对靶细胞的调控上各文献报道结论不一[5, 7-10]。NPY通过Y1受体促进BMSCs增殖和成骨分化[8, 11-13];NPY通过Y1受体抑制了成骨细胞分化和BMSCs的增殖[14-15]。动物实验发现,当特异性敲除Y1受体后,小鼠股骨的松质骨体积、骨小梁厚度和数量均明显增加[10, 15],提示Y1受体可能抑制成骨作用[16];也有文献发现敲除Y1受体基因小鼠可导致骨折愈合延迟[17]。Y1受体在骨代谢中的作用存在争议,机制不明。因此本研究拟通过阻断Y1受体,进一步直接说明Y1受体的对体外培养BMSCs成骨分化的机制,并通过局部注射Y1受体拮抗剂观察对骨缺损修复的影响,从体内和体外共同探讨Y1受体在外周骨代谢中的可能作用。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验动物SPF级体质量80~100 g或280~320 g雄性Sprague Dawley大鼠(南方医科大学动物实验中心提供),动物的使用方案获得南方医科大学动物医学伦理委员会审查批准,并严格遵循美国NIH有关实验动物照料及使用的指南。

1.2 BMSCs获取、培养、成骨诱导分化选用体质量80~100 g SD雄性大鼠,取两侧股骨,用5 mL注射器吸取L-DMEM(Gibco,美国)将骨髓冲出,形成单细胞悬液。用10%胎牛血清(FBS,Gibco,澳大利亚)的L-DMEM,以2×106密度接种于25 cm2培养瓶,培养箱中孵育(37 ℃,5% CO2),每2~3 d换全液1次,细胞贴壁融合到80%左右进行传代培养,第3代细胞接种于12孔板,1×104/孔,进行成骨诱导分化培养(L-DMEM, 50 μg/mL维生素C,100 nmol/L地塞米松和10 mmol/L β-甘油磷酸)。随机分为4组,对照组(等体积PBS),终浓度分别为10-6、10-7、10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂组(PD160170,Abcam,美国,分别为高、中、低浓度组)[12-13],每2~3 d换液,每次换液均加入相应刺激物。

1.3 碱性磷酸酶(ALP)染色室温下用4%多聚甲醛固定10 min,按说明书配制碱性磷酸酶染液(上海碧云天生物技术有限公司,上海),弃固定液,PBS清洗2遍,12孔板每孔加染液400 μL覆盖细胞膜,避光染色1 h,弃染液,自来水洗2遍终止染色,晾干,光学显微镜下观察拍照,IPP 6.0进行分析比较ALP染色的程度。

1.4 茜素红染色以70%乙醇固定细胞1 h,PBS洗3次,茜素红溶液(Sigma,Tris-HCl配制0.1%茜素红溶液,pH值为8.3)染色30 min后PBS洗3遍,置于光学显微镜下观察,IPP 6.0计算矿化结节面积。

1.5 Western blot法收集细胞,提取总蛋白,采用Bradford法测定总蛋白质浓度,每孔上样40 μg,进行SDS-PAGE电泳,转膜,5%脱脂牛奶液封闭l h。以β-actin为内参,加抗-Collagen Ⅰ(Santa,1:200)、抗-Runx2(abcam,1:1000)、抗-Osteocalcin(abcam,1:1000)孵育4 ℃过夜,PBS洗3次,10 min/次,加入相应二抗,室温孵育l h,化学发光液染色后进行观察和图像分析。

1.6 q-PCR法通过q-PCR检测大鼠细胞I型胶原(COLI)、骨钙素(OCN)和Runt相关转录因子2(Runx2)基因表达水平。GenBank上查找目的基因mRNA序列(表 1),通过Trizol提取细胞RNA,进行总RNA纯度和完整性检测,最后进行逆转录反应,选择GAPDH作为内参。

| 表 1 成骨相关基因COLI、OCN、Runx2基因的序列 Table 1 Gene sequences of osteogenesis-related genes COLI, OCN, and Runx2 |

将雄性SD大鼠(280~300 g)随机分为3组,每组6只。其中A组为等体积PBS(对照组),B组为10-6 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂(高浓度组),C组为10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂(低浓度组)。通过腹腔注射2%戊巴比妥钠溶液(50 mg/kg)麻醉SD大鼠,手术暴露双侧股骨干骺端约1 cm,股骨髁上0.5 cm处利用医用慢速直流电钻(直接为2.5 mm)由前向后钻通双侧骨皮质,形成直径为2.5 mm的圆柱形缺损[18]。术后1周行X线检查排除骨折后,各组于股骨内外侧髁上骨缺损区内垂直注射上述对应各组试剂,各组每次注射0.2 mL,1次/d,连续注射28 d。

1.8 Micro-CT检测将股骨远端标本通过Micro-CT检测(Skyscan, 德国),对大鼠双侧股骨进行8 µm薄层扫描,扫描范围为股骨干骺端骨缺损近端、远端5 mm。通过配套软件CTan、CTvox将标本从冠状面、矢状面进行分析并建立出圆柱形骨缺损,同时计算标本骨体积分数、骨表面积和骨体积的比值、骨小梁数量、骨小梁厚度等。

1.9 统计学方法利用SPSS19.0软件,实验数据以均数±标准差表示。采用单因素方差分析比较各组的检测指标的平均值,用Bonferroni法进行不同组的数据的两两比较,P < 0.05认为差异具有统计学意义。

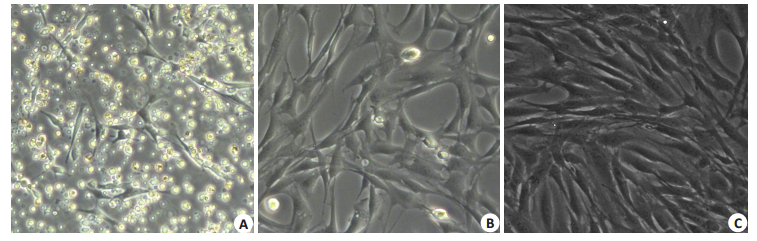

2 结果 2.1 BMSCs细胞培养、鉴定原代BMSCs培养24 h后即可见一些单个的黏附贴壁细胞,呈纺锤状或多边形(图 1A);3~5 d细胞增殖迅速,形成克隆细胞群,呈梭形、多突状的成纤维样细胞,7~9 d可达80%融合;传代3~5 d后细胞贴壁铺展、呈均一的长梭形、漩涡状或束状平行排列(图 1B,C),第3代经过流式鉴定可获得高纯度BMSCs[13]。

|

图 1 BMSCs原代、传代形态 Figure 1 Morphology of BMSCs in primary culture (A) and in the first (B) and third (C) passages (Original magnification: × 100). |

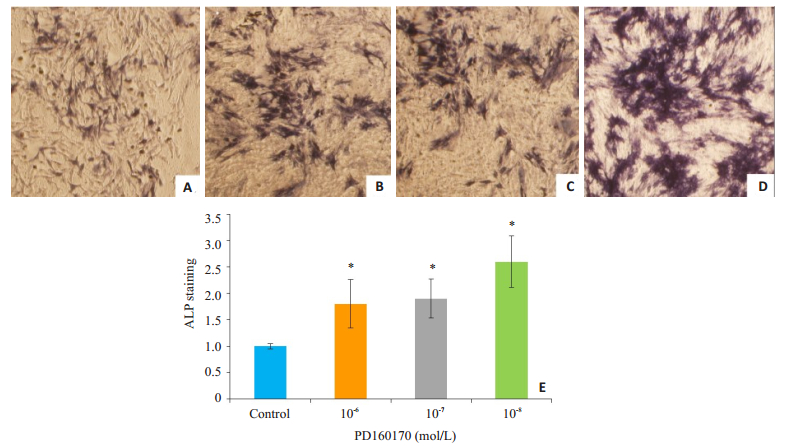

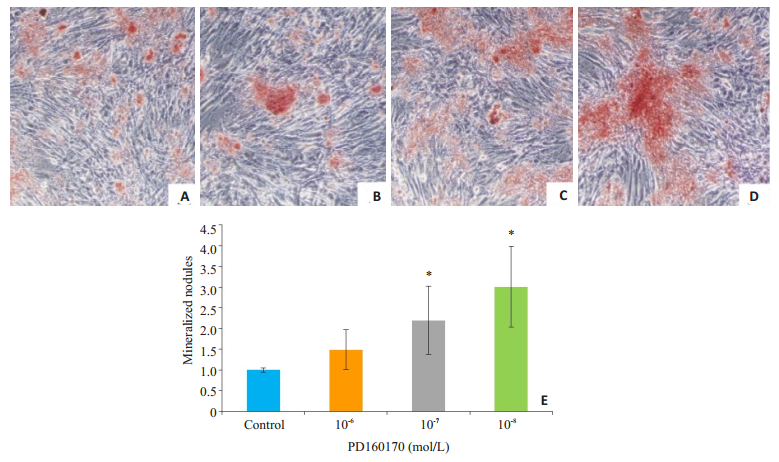

成骨分化诱导7 d,通过ALP染色发现,与对照组相比,10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂组BMSCs细胞内ALP染色强度即棕褐色的阳性细胞比例明显提高,差异有统计学意义(P=0.005);10-6 mol/L和10-7 mol/L浓度的Y1受体拮抗剂对于ALP的表达有促进作用(图 2)。茜素红染色结果显示,成骨诱导分化14 d对照组细胞外基质可见少量红染矿化结节,而Y1受体拮抗剂组红染矿化结节明显增多,以10-8 mol/L浓度最为明显,差异有统计学意义(P=0.03,图 3)。

|

图 2 7 d Y1受体拮抗剂促进BMSCs成骨分化中碱性磷酸酶的表达 Figure 2 NPY Y1 receptor antagonist enhances expression of alkaline phosphatase in BMSCs on day 7 of osteogenic differentiation (ALP staining, × 100). A: Control group; B-D: 10-6, 10-7, and 10-8 mol/L Y1 receptor antagonist groups, respectively; E: Comparison of ALP expressions among the 4 groups. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

|

图 3 14 d Y1受体拮抗剂促进BMSC成骨分化中矿化结节的形成 Figure 3 NPY Y1 receptor antagonist promotes formation of mineralized nodules in the extracellular matrix in BMSCs on day 14 of osteogenic differentiation (Alizarin red staining, ×100). A: Control group; B-D: 10-6, 10-7, and 10-8 mol/L Y1 receptor antagonist groups, respectively; E: Comparison of the intensity of mineralized nodules among the 4 groups. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

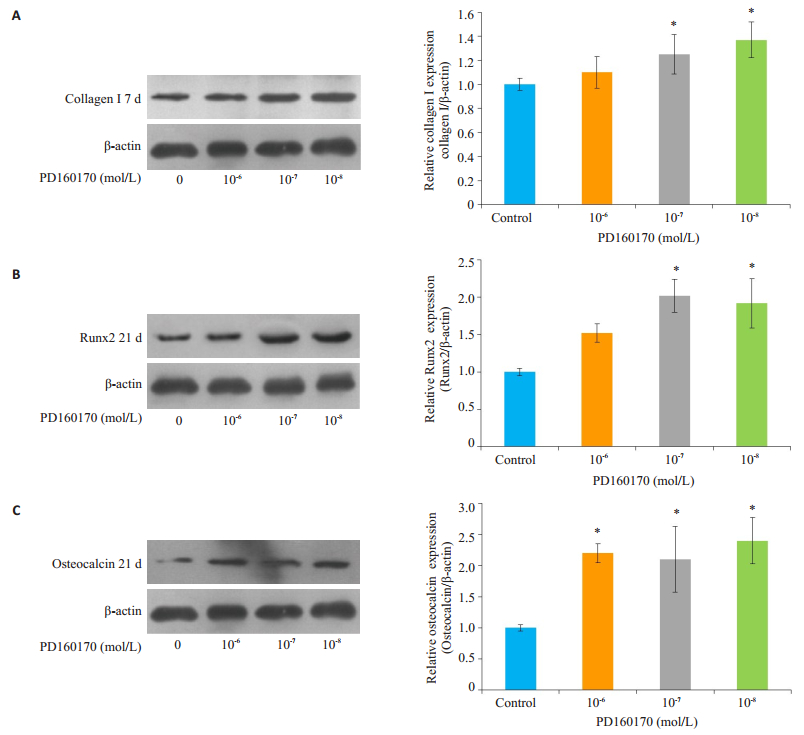

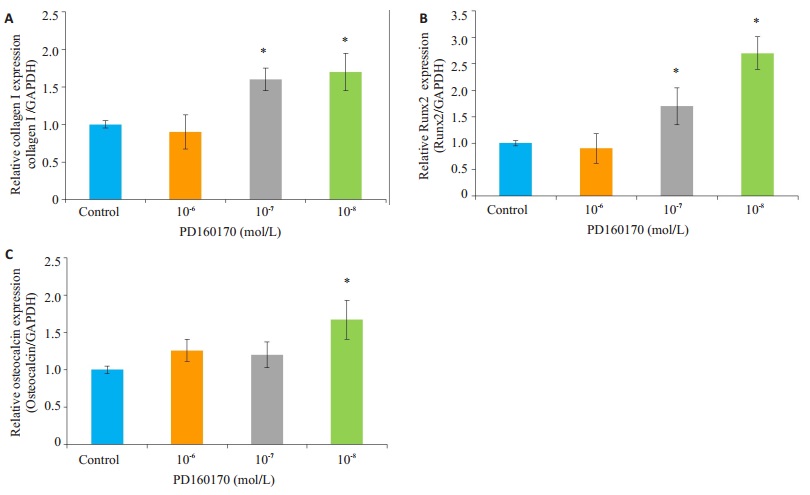

在成骨诱导第7天,10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂组COLI蛋白表达水平高于对照组,差异具有统计学意义(P=0.03),而高、中浓度组差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05,图 4A);在成骨诱导第21天,低、中度浓度组Runx2蛋白表达水平明显高于对照组,分别为对照组的2.0和1.9倍,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 4B);Y1受体拮抗剂组OCN蛋白表达水平高于对照组,高、中、低三浓度组分为对照组的2.2、2.1、2.4倍,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.001,图 4C)。同时通过对BMSCs成骨诱导分化过程中COLI、OCN、Runx2基因的检测,发现10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂可有效促进第7天COLI基因(1.7±0.25),第21天OCN基因(1.6±0.26)、Runx2基因(2.7±0.31)的表达,差异均具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 5)。

|

图 4 Y1受体拮抗剂对BMSCs成骨诱导分化过程中COLI、Runx2、OCN蛋白表达的影响 Figure 4 Comparison of the expressions of COLI, Runx2 and OCN proteins among control, 10-6, 10-7, and 10-8 mol/L Y1 receptor antagonist groups. A: Expression of COLI protein on day 7; B, C: Expressions of Runx2 and OCN proteins on day 21. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

|

图 5 Y1受体拮抗剂对BMSCs成骨诱导分化过程中COLI、Runx2、OCN mRNA表达的影响 Figure 5 Comparison of the expressions of osteogenic differentiation-related mRNA in cells treated with different concentrations (10-6, 10-7, 10-8 mol/L) of Y1 receptor antagonist. A: COLI mRNA expression at 7 days; B, C: Runx2 and OCN mRNA expressions at 21 days. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

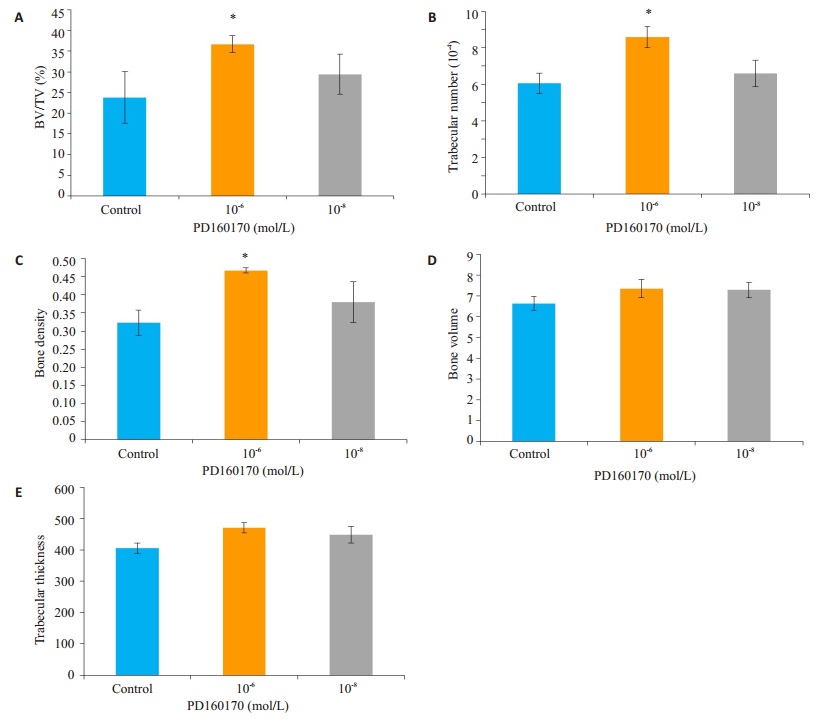

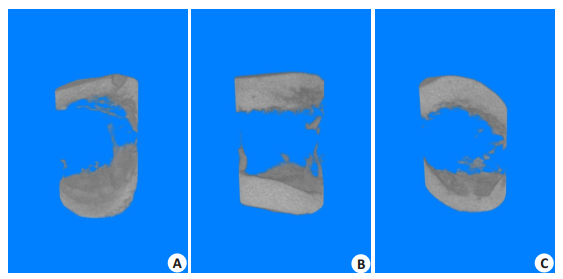

每日局部注射0.2 mL浓度为10-6、10-8 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂及等体积PBS溶液,连续注射28 d后,通过Micro-CT扫描三维重建圆柱形骨缺损部分结果发现,10-6 mol/L组大鼠骨缺损部分平均BV/TV、骨小梁数量、骨密度等高于对照组,且差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 6A~C),同时发现骨小梁厚度(P=0.07)、骨体积(P=0.35)与对照组相比,差异无统计学意义(图 6D,E)。而与对照组相比,10-8 mol/L浓度组对上述参数无明显促进骨缺损愈合作用(图 6、7)。

|

图 6 Y1受体拮抗剂对骨缺损中BV/TV、骨小梁数量、股小梁厚度、骨密度、骨体积等影响 Figure 6 Comparison of bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV, A), trabecular number (B), bone density (C), bone volume (D), and trabecular thickness (E) in rats with local injection of different concentrations (10-6 and 10-8 mol/L) of Y1 receptor antagonist for 28 days, with PBS as control. *P < 0.05 vs control group. |

|

图 7 Y1受体拮抗剂不同浓度组大鼠股骨缺损Micro-CT三维重建 Figure 7 Micro-CT 3D reconstruction of femoral defects in rats. A: Control group; B, C: 10-6 and 10-8 mol/L Y1 receptor antagonist groups, respectively. |

NPY可通过结合其特异性Y受体,尤其是Y1受体和Y2受体,来调节成骨细胞和破骨细胞的活性,从而实现骨的生理与病理过程中的重要作用[6, 19-20]。以往较多文献的研究主要通过直接加入外源性NPY刺激[12-13, 21],或者通过种系或部分基因敲除Y1或Y2受体来研究Y1受体在BMSCs增殖、成骨分化的作用[10, 15, 22],其结果表明NPY对BMSCs成骨分化的影响可能与Y1受体表达的变化相关[22]。本研究通过体外实验直接加入Y1受体拮抗剂干预,发现其可以调控BMSCs成骨分化,包括促进ALP的表达以及矿化结节的形成,同时发现成骨相关蛋白或基因(COLI、OCN、Runx2)表达也相应提高,从而直接证明Y1受体在BMSCs成骨分化中可能起抑制作用。

以往研究表明BMSCs成骨诱导分化过程中Y1受体蛋白水平以时间依赖性的方式减少,间接提示Y1受体通路可能介导抑制BMSCs成骨分化的作用[23]。同时已有文献报道在成骨前细胞MC3T3-E1细胞中,转入Y1受体沉默子siRAN后,Y1受体表达明显下降,而ALP、OCN、Runx2等成骨标志物表达上升,提示Y1受体抑制MC3T3-E1成骨分化[24-25]。因此拮抗Y1受体可作为预防或治疗骨质疏松症的药物靶点之一[26]。同时我们猜想在BMSCs诱导成骨分化过程中,Y1受体的表达是个动态变化过程,可能是信号通路不可缺少的一部分,而相关结论需进一步研究验证。

本次体内实验,通过局部注射终浓度为10-6 mol/L Y1受体拮抗剂28 d,三维重建大鼠骨缺损部分后,发现平均BV/TV、骨小梁数量、骨密度均高于对照组,提示外周Y1受体拮抗剂可促进骨缺损修复。尽管以往研究通过种系敲除Y1受体的小鼠和成骨细胞特异性敲除Y1受体的小鼠均表现出较高的骨形成速率和较多的骨量形成[5, 15, 21],但存在一定的局限性。在种系特异性受体敲除中易引起相关其他受体的改变,如种系敲除Y2受体引起干细胞Y1受体表达下调[22];在BMSCs成骨分化时加入NPY及Y2受体特异性激动剂PYY会引起Y1受体mRNA的表达下降[27]。通过特异性敲除成骨细胞表面Y1受体,发现小鼠松质骨骨量、骨小梁数量、骨小梁厚度、骨形成率以及骨矿化沉积率明显增高[10]。但是外周骨组织周围除了成骨细胞外,BMSCs、骨祖细胞以及成骨前细胞MC3T3细胞表面均有Y1受体表达[12-13, 24],为此通过单纯某种细胞Y1受体敲除技术,只能得出相应细胞Y1受体在骨代谢中作用。小鼠口服Y1受体拮抗剂BIBO3304 8周后可以促进骨的形成和骨量增加,其原因可能为阻断Y1受体后,增加成骨细胞活性进而提高骨量,且对体质量、食物摄取、能量代谢等均无影响[7, 28]。但Y1受体广泛分布于外周及中枢神经系统,无法避免Y1受体对中枢系统其它未知功能的影响,如免疫系统、脂肪代谢等[26]。因此选择局部注射Y1受体拮抗剂可能是研究其对骨代谢效应更直观的方式。通过本研究我们更有理由提出Y1受体通路在外周可能不是调控BMSCs成骨分化的积极因素,甚至是一种能够产生负性调节的因素。但也有文献发现种系敲除Y1受体基因后小鼠发生骨折愈合延迟,而单独敲除成骨细胞上Y1受体的小鼠对骨折愈合无明显影响[17],其可能原因是前者降低了破骨细胞的活性,导致骨折愈合过程中炎症反应时间和软骨骨化时间延长。

本研究认为,NPY作为一种特异性结合Y1受体蛋白表达动态调控具有双向效应的神经肽,对于具有成骨分化潜能且分化程度较低的成骨相关细胞(如BMSCs及成骨前体细胞),在没有施加干预因素情况下常规表达Y1受体,而NPY通过Y1受体发挥其抑制成骨分化的作用;若成骨分化强制启动后(通过成骨诱导培养基的作用),Y1受体表达下降,发挥促进成骨分化作用。此外也有文献报道Y5受体在骨髓细胞中表达, 并且已经有研究证明Y5受体在体外环境中能引起骨髓细胞增殖[11, 29]。在小鼠中缺乏Y6受体信号的转导可导致成骨细胞数目的增加和破骨细胞数量的减少[30], 但Y5和Y6受体在骨调节中的作用还有待确定[6, 9, 29]。

本研究通过体内外实验研究发现NPY Y1受体拮抗剂可促进BMSCs成骨分化以及骨缺损的修复,提示外周Y1受体为抑制成骨作用,为预防或治疗骨质疏松症及调控骨代谢相关药物靶点的发现和确认提供了新的研究思路。

| [1] |

Yang TY, Wang TC, Tsai YH, et al. The effects of an injury to the brain on bone healing and callus formation in young adults with fractures of the femoral shaft[J].

J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2012, 94B(2): 227-30.

|

| [2] |

Allison SJ, Baldock P, Sainsbury A, et al. Conditional deletion of hypothalamic Y2 receptors reverts gonadectomy-induced bone loss in adult mice[J].

J Biol Chem, 2006, 281(33): 23436-44.

DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M604839200. |

| [3] |

Horsnell H, Baldock PA. Osteoblastic actions of the neuropeptide Y system to regulate bone and energy homeostasis[J].

Curr Osteoporos Rep, 2016, 14(1): 26-31.

DOI: 10.1007/s11914-016-0300-9. |

| [4] |

Franquinho F, Liz MA, Nunes AF, et al. Neuropeptide Y and osteoblast differentiation - the balance between the neuroosteogenic network and local control[J].

FEBS J, 2010, 277(18): 3664-74.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07774.x. |

| [5] |

Lee NJ, Herzog H. NPY regulation of bone remodelling[J].

Neuropeptides, 2009, 43(6): 457-63.

DOI: 10.1016/j.npep.2009.08.006. |

| [6] |

Khor EC, Baldock P. The NPY system and its neural and neuroendocrine regulation of bone[J].

Curr Osteoporos Rep, 2012, 10(2): 160-8.

DOI: 10.1007/s11914-012-0102-7. |

| [7] |

Sousa DM, Baldock PA, Enriquez RF, et al. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonism increases bone mass in mice[J].

Bone, 2012, 51(1): 8-16.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.020. |

| [8] |

Ma WH, Zhang XE, Shi SS, et al. Neuropeptides stimulate human osteoblast activity and promote gap junctional intercellular communication[J].

Neuropeptides, 2013, 47(3): 179-86.

DOI: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.12.002. |

| [9] |

Matic I, Matthews BG, Kizivat T, et al. Bone-specific overexpression of NPY modulates osteogenesis[J].

J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact, 2012, 12(4): 209-18.

|

| [10] |

Lee NJ, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, et al. Osteoblast specific Y1 receptor deletion enhances bone mass[J].

Bone, 2011, 48(3): 461-7.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.174. |

| [11] |

Igura K, Haider HKh, Ahmed RP, et al. Neuropeptide y and neuropeptide y y5 receptor interaction restores impaired growth potential of aging bone marrow stromal cells[J].

Rejuvenation Res, 2011, 14(4): 393-403.

DOI: 10.1089/rej.2010.1129. |

| [12] |

Liu S, Jin D, Wu JQ, et al. Neuropeptide Y stimulates osteoblastic differentiation and VEGF expression of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells related to canonical Wnt signaling activating in vitro[J].

Neuropeptides, 2016, 56(2): 105-13.

|

| [13] |

Wu JQ, Liu S, Meng H, et al. Neuropeptide Y enhances proliferation and prevents apoptosis in rat bone marrow stromal cells in association with activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in vitro[J].

Stem Cell Res, 2017, 21(3): 74-84.

|

| [14] |

Igwe JC, Jiang X, Paic F, et al. Neuropeptide Y is expressed by osteocytes and can inhibit osteoblastic activity[J].

J Cell Biochem, 2009, 108(3): 621-30.

DOI: 10.1002/jcb.v108:3. |

| [15] |

Lee NJ, Doyle KL, Sainsbury A, et al. Critical role for Y1 receptors in mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation and osteoblast activity[J].

J Bone Miner Res, 2010, 25(8): 1736-47.

DOI: 10.1002/jbmr.61. |

| [16] |

Shi YC, Baldock PA. Central and peripheral mechanisms of the NPY system in the regulation of bone and adipose tissue[J].

Bone, 2012, 50(2, SI): 430-6.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.001. |

| [17] |

Sousa DM, Mcdonald MM, Mikulec KA, et al. Neuropeptide Y modulates fracture healing through Y- 1 receptor signaling[J].

J Orthop Res, 2013, 31(10): 1570-8.

DOI: 10.1002/jor.22400. |

| [18] |

Miron RJ, Wei LF, Bosshardt DD, et al. Effects of enamel matrix proteins in combination with a bovine-derived natural bone mineral for the repair of bone defects[J].

Clin Oral Investig, 2014, 18(2): 471-8.

DOI: 10.1007/s00784-013-0992-5. |

| [19] |

Graessel S, Muschter D. Do neuroendocrine peptides and their receptors qualify as novel therapeutic targets in osteoarthritis?[J].

Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(2): 45.

|

| [20] |

Peng S, Zhou YL, Song ZY, et al. Effects of neuropeptide Y on stem cells and their potential applications in disease therapy[J].

Stem Cells Int, 2017, 25(8): 6823917.

|

| [21] |

Baldock PA, Allison SJ, Lundberg P, et al. Novel role of Y1 receptors in the coordinated regulation of bone and energy homeostasis[J].

J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(26): 19092-102.

DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M700644200. |

| [22] |

Lundberg P, Allison SJ, Lee NJ, et al. Greater bone formation of Y2 knockout mice is associated with increased osteoprogenitor numbers and altered Y1 receptor expression[J].

J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(26): 19082-91.

DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M609629200. |

| [23] |

王钊, 金丹, 陀泳华, 等. 神经肽Y受体在骨髓间充质干细胞成骨分化过程中的表达[J].

中华创伤杂志, 2011, 27(1): 72-7.

|

| [24] |

Kurebayashi N, Sato M, Fujisawa T, et al. Regulation of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor expression by bone morphogenetic protein 2 in C2C12 myoblasts[J].

Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2013, 439(4): 506-10.

DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.014. |

| [25] |

Yahara M, Tei K, Tamura M. Inhibition of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor induces osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3E1 cells[J].

Mol Med Rep, 2017, 16(3): 2779-84.

DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6866. |

| [26] |

Sousa DM, Herzog H, Lamghari M. NPY signalling pathway in bone homeostasis: Y1 receptor as a potential drug target[J].

Curr Drug Targets, 2009, 10(1): 9-19.

DOI: 10.2174/138945009787122888. |

| [27] |

Teixeira L, Sousa DM, Nunes AF, et al. NPY revealed as a critical modulator of osteoblast function in vitro: new insights into the role of Y1 and Y2 receptors[J].

J Cell Biochem, 2009, 107(5): 908-16.

DOI: 10.1002/jcb.v107:5. |

| [28] |

Loh K, Shi YC, Walters S, et al. Inhibition of Y1 receptor signaling improves islet transplant outcome[J].

Nat Commun, 2017, 8(1): 490.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-00624-2. |

| [29] |

Alves CJ, Alencastre IS, Neto E, et al. Bone injury and repair trigger central and peripheral NPY neuronal pathways[J].

PLoS One, 2016, 11(11): e0165465.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165465. |

| [30] |

Khor EC, Yulyaningsih E, Driessler F, et al. The y6 receptor suppresses bone resorption and stimulates bone formation in mice via a suprachiasmatic nucleus relay[J].

Bone, 2016, 84(7): 139-47.

|

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38