2. 军事科学院军事医学研究院辐射医学研究所,北京 100850;

3. 解放军总医院第一附属医院麻醉科,北京 100048;

4. 解放军第307医院麻醉科,北京 100071

2. Beijing Institute of Radiation Medicine, Academy of Military Medical Science, Beijing 100850, China;

3. First Affiliated Hospital of PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100048, China;

4. Department of Anesthesiology, 307 Hospital of PLA, Beijing 100071, China

随着医学进步,越来越多新生儿及婴幼儿在全身麻醉或监测麻醉下接受手术、有创或影像学检查,麻醉明显提高了新生儿、婴幼儿的配合度及舒适度。于此同时,麻醉药对于发育期大脑的影响也受到越来越多的关注。研究显示[1],患儿在3岁前多次接受全身麻醉与学习能力障碍和注意力缺陷/多动症的发生率增加存在相关性,但目前临床研究尚未得到确切结论[2-5]。

丙泊酚作为临床上最常使用的短效静脉麻醉药,1989年美国FDA通过并推荐临床使用,1999年荷兰和瑞士批准丙泊酚应用于婴幼儿麻醉。但丙泊酚对于发育期大脑的影响目前尚无确切结论[6-8]。手术创伤可引起高水平肾上腺皮质激素及氧化应激而诱导c-fos表达的增加[9]。因此,我们通过设计“局麻剖腹探查手术”和“丙泊酚麻醉”双因素研究,观察手术创伤及丙泊酚麻醉对幼鼠近期、远期神经发育、行为学的影响及就相关机制进行探讨,为临床上新生儿及婴幼儿手术时机及麻醉药物的合理选择提供参考,同时为优化麻醉管理可能在婴幼儿围术期神经功能中的保护作用提供理论依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验动物SD大鼠,10日龄,雌雄各半,体质量18~25 g,由北京维通利华公司提供(动物合格证号:SCXK(京)2016-0011),且已通过解放军总医院伦理委员会审查。适应环境3 d,室温20~25 ℃,湿度60%~70%,空气新鲜,通气良好,与母鼠共同饲养。

1.2 主要药品、试剂与实验仪器丙泊酚注射液(10 mg/mL,AstraZeneca,批号:MV039);盐酸罗哌卡因注射液(75 mg/mL,Astra Zeneca,H20140763);大鼠TNF-a ELISA检测试剂盒(abcam,产品编号:ab100785);雷勃MK3酶标仪(Thermo, USA);3-18K高速低温离心机(Startorius, Germany);全自动组织匀浆仪(Roche, USA)。

1.3 实验模型建立及分组实验模型:(1)局麻腹部手术:将幼鼠用胶带固定于加热毯(37 ℃),腹部备皮、消毒、铺单,0.1 mL 0.5%罗哌卡因逐层麻醉,行约2.5 cm腹部正中切口,暴露腹腔,无菌钳依次探查肝、脾、胃、小肠、结肠等内脏后,丝线逐层缝合肌肉和皮肤,手术历时1 h。(2)假手术:幼鼠固定、备皮、消毒,不手术。(3)丙泊酚麻醉:腹腔注射丙泊酚注射液75 mg/kg。

实验分组:104只13日龄(P13)SD幼鼠,按体质量编号,CHISS软件随机分为4组,每组26只,即对照组(con组)、丙泊酚组(ppf组)、手术组(sur组)、丙泊酚+手术组(ppf+sur组)。con组腹腔注射7.5 mL/kg生理盐水后行假手术。ppf+sur组于丙泊酚麻醉翻正反射消失后行局麻手术。模型建立后每组随机分成两个亚组,一组于术后1 d行海马TNF-α、脑组织caspase-3、c-fos检测,另一组分笼饲养至60日龄(P60)时行Morris水迷宫、海马TNF-α、脑组织caspase-3、c-fos检测。

1.4 ELISA法检测海马组织中TNF-α的含量每组随机选取8只于模型建立后1 d取海马组织行ELISA检测。幼鼠断头处死,冰上取脑,分离海马,液氮保存。称取40 mg标本,加入RIPA裂解液、蛋白酶抑制剂、磷酸酶抑制剂PMSF,震荡匀浆、裂解,离心,取上清液行ELISA法检测。另一亚组于60 d行为学检测后每组选取8只取海马组织行TNF-α检测。

1.5 免疫组化法检测脑组织中caspase-3、c-fos的表达每组随机选取5只于模型建立后1 d,腹腔注射10%水合氯醛35 mg/kg麻醉,开胸暴露心脏,经左心室插管,连接灌注系统,剪开右心耳作为灌注液流出口。快速灌注生理盐水至流出液澄清、肝脏颜色均匀变白后,缓慢灌注4%多聚甲醛内固定。取脑组织,置于4%多聚甲醛中固定24 h。采用免疫组织化学法检测caspase-3、c-fos的表达。常规石蜡包埋,连续切取厚度为4 μm的切片,切片二甲苯、常规梯度酒精浸泡至脱蜡,3% H2O2封闭内源性过氧化物酶,柠檬酸缓冲液抗原修复,滴加一抗(caspase-3抗体,c-fos抗体,稀释浓度为1:100,购自美国abcam公司),4 ℃孵育24 h,依次滴加二抗(山羊抗兔二抗工作液,PV-9001试剂盒,北京中杉金桥生物技术有限公司),每步操作间用0.01 mol/L PBS缓冲液冲洗5 min×3次,DAB显色,脱水透明后封片。光镜下观察(40×),采用image Pro图像分析处理系统进行分析。另一亚组于大鼠60 d行为学检测后每组随机选取5只行免疫组化检测。

1.6 Morris水迷宫实验(MWM)评估大鼠空间学习和记忆能力。直径1.2 m、深0.5 m圆形泳池,注满22±1 ℃水,深30 cm,分为4个象限。定位航行训练:水池按方位平均分成4个象限,将直径10 cm的平台置于第一象限内,没于水面下1.5 cm。将大鼠置于第一象限中点面朝池壁放入水中,若大鼠找到平台,记录其找到平台时间(s),即“登台潜伏期”,并在圆台上停留10 s,如果大鼠60 s内未找到水下平台,则时间记为60 s,并将大鼠放到圆台停留10 s;将动物移开、擦干、灯下烤5 min、放回笼内,所有大鼠训练结束后,依次行2~4象限训练,每只大鼠每天训练4次,连续训练5 d,同时记录大鼠游泳速度。第6天行空间探索实验:撤掉平台,将大鼠置于平台象限对侧象限面朝池壁放于水中,记录60 s内大鼠“目标象限停留时间”和“穿过原平台所在位置的次数。”

1.7 统计学处理采用SPSS 22.0统计学软件进行分析,计量资料以均数±标准差表示,组间比较采用析因设计的方差分析,两两比较采用LSD检验,水迷宫采用重复测量的方差分析,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

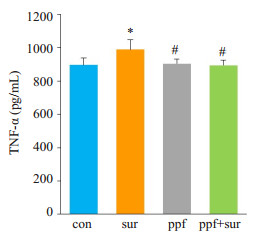

2 结果 2.1 13日龄幼鼠海马组织TNF-α、脑组织caspase-3,c-fos的表达模型建立后1 d,海马组织中TNF-α的含量(图 1)。与con组相比,sur组海马组织TNF-α含量升高(P < 0.05);而与sur组相比,ppf+sur组海马组织TNF-α含量降低(P < 0.05);ppf组、ppf+sur组与con组相比,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。

|

图 1 13日龄幼鼠海马组织TNF-α浓度 Figure 1 Concentration of TNF-α in the hippocampus of the P13 SD rats. *P < 0.05 vs con group; #P < 0.05 vs sur group |

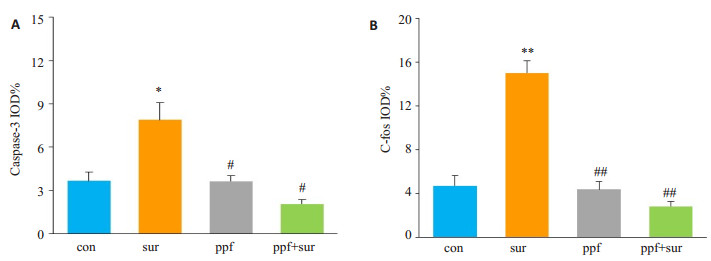

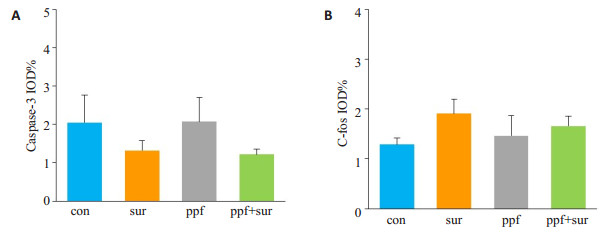

Caspase-3、c-fos的表达结果显示(图 2),与con组相比,sur组脑组织caspase-3(P < 0.05)、c-fos表达增加(P < 0.01);而与sur组相比,ppf+sur组脑组织caspase-3(P < 0.05)、c-fos表达减少(P < 0.01);ppf组、ppf+sur组与con组相比,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。

|

图 2 13日龄幼鼠脑组织切片中caspase-3、c-fos的表达 Figure 2 Expression of caspase-3 and c-fos in the brain of the P13 rats. A: caspase-3; B: c-fos. *P < 0.05 vs con group; #P < 0.05 vs sur group; **P < 0.01 vs con group; ##P < 0.01 vs sur group |

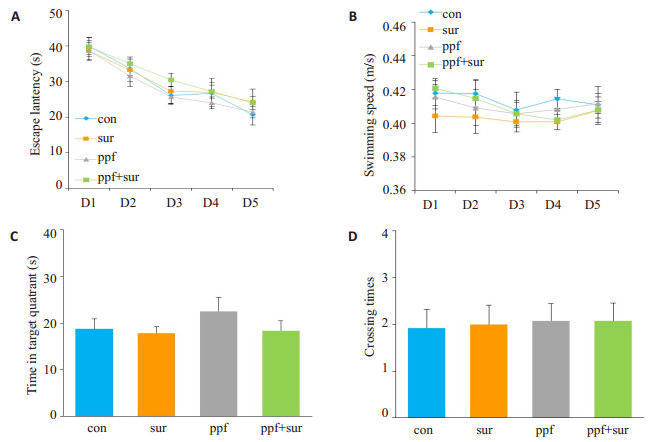

水迷宫结果显示(图 3),4组大鼠之间游泳速度差异无统计学意义;con组、sur组、ppf组、ppf+sur组登台潜伏期差异无统计学意义;参考记忆测试中,目标象限停留时间及穿台次数各组之间差异无统计学意义。

|

图 3 60日龄成鼠Morris水迷宫试验情况 Figure 3 Morris water maze test results in the 4 groups. A: Escape latency in navigation training; B: Swimming speed; C, D: Time in target quadrant (C) and crossing times (D) |

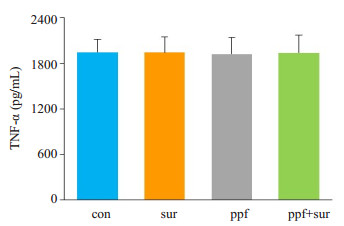

水迷宫测试完成后,取大鼠海马组织行TNF-α ELISA检测,结果显示(图 4),各组大鼠之间差异无统计学意义。免疫组化法检测脑组织caspase-3、c-fos的表达结果显示(图 5),各组之间差异无统计学意义。

|

图 4 60日龄成鼠海马组织TNF-α浓度 Figure 4 Concentration of TNF-α in the hippocampus of the P60 SD rats |

|

图 5 60日龄成鼠脑组织切片中caspase-3、c-fos的表达 Figure 5 Expression of caspase-3 and c-fos in the brain of the P60 rats. A: caspase-3; B: c-fos |

FDA于近期发出一项引发广泛关注的药物安全通告[10]:孕妇或儿童多次或长时间使用全身麻醉或镇静药物,可能会伤害孕妇所怀胎儿或3岁以下儿童的大脑。由此,婴幼儿手术或麻醉时机的选择也成为研究热点。以往有许多研究中选择出生后7 d的SD大鼠单次或多次给予丙泊酚暴露来研究麻醉对大脑的影响[6-7, 11],但7日龄SD大鼠与人类年龄对应很难转换。而本研究拟观察从新生儿期(出生后28 d)至早期婴儿期(< 3月)丙泊酚麻醉和手术创伤双重因素对发育期大脑的影响,而13日龄SD幼鼠相当于人类41 d[12],60日龄大鼠相当于人类13岁左右。加之预实验发现7日龄幼鼠难以耐受开腹手术,因此选择13日龄SD幼鼠作为研究对象,大鼠60日龄作为研究终点。

本实验研究发现局麻腹部手术下13 d龄幼鼠海马组织中TNF-α释放增多,脑组织c-fos、caspase-3蛋白表达增加,海马神经元凋亡增加。已有研究发现,手术创伤后产生的致炎因子能够导致认知功能的减退[13-15]。而海马对于炎症反应极为敏感[16], 这在术后大鼠的空间学习记忆[17-18]、恐惧记忆[19-21]等测试中已得到证实。TNF-α是脑组织损伤后较早释放的具有多种生物学效应的重要促炎细胞因子,c-fos是即刻早期癌基因家族成员中的一种,是神经元激活和参与兴奋反应活动的开始,TNF-α与c-fos的过量表达均可产生神经毒性[22],加速细胞凋亡。caspase-3作为促凋亡信号转导通路的重要效应酶,是凋亡途径的执行者,也是细胞凋亡的特征性标志。手术创伤促使海马炎症介质释放增多,使神经胶质细胞产生Fos蛋白[23],c-fos表达升高,通过调控其下游靶基因从而使一些维持细胞生存的蛋白合成减少,杀手蛋白增加,加速海马神经元的凋亡。姚星等研究[24-25]结果表明,手术创伤能导致海马炎症介质释放增多,Fos蛋白表达增高,且与神经细胞凋亡呈正相关。这些结果均与本研究结果一致。

本研究还发现,单次给予丙泊酚麻醉不会引起13 d龄SD幼鼠海马炎性介质释放增多以及caspase-3、c-fos表达增加,同时丙泊酚还能缓解手术创伤引起的上述影响。已有研究证实,丙泊酚对大脑具有保护作用,这可能是因为丙泊酚能够降低大脑氧代谢率、降低颅内压,减少兴奋性谷氨酸神经递质的释放及神经毒性引起的病理性改变,抑制脂质过氧化,防止蛋白变性,减少炎症介质的释放,进而减少/抑制细胞凋亡,从而对大脑产生保护作用。Li等[26-27]研究结果说明,丙泊酚可在一定程度上抑制NF-κB的活化和caspase-3、TNF-α的高度表达,阻止炎性级联反应的进一步扩大,通过抑制神经元凋亡实现对脑组织的保护作用。这些结论均与本研究结论一致。

认知活动是脑的高级神经活动,也是重要的智力因素,学习、记忆是其组成部分。本研究也证实单次给予13 d龄SD幼鼠局麻腹部手术及丙泊酚麻醉在其60 d时不会出现学习记忆功能的受损。Anders等[28]也发现,新生10 d龄小鼠单次注射60 mg/kg丙泊酚后其成年认知功能并未减退,与本研究结果一致。大鼠学习记忆的快速发育期是妊娠的末期以及出生后2周,该时期未成熟的神经系统对内外环境的变化具有高度的敏感性。同时出生后2周也正是神经发育高峰期,此期的神经系统具有很强的适应与损伤的自我修复功能[29]。随着炎症、凋亡诱导因素的消失,神经干细胞的激活与损伤修复的进行,内源性神经干细胞增殖分化,海马神经元的损伤逐渐被代偿,从而修复大鼠的神经网络结构。这可能是各组大鼠在60 d时未检测出认知功能、神经功能损伤的原因。

综上所述,幼鼠接受局麻手术可引起大脑炎症介质释放增多以及caspase-3、c-fos的表达增加。但此类手术创伤所产生的影响不会持续至大鼠成年。同时,单次丙泊酚麻醉不会对幼鼠中枢神经系统产生影响,同时还能缓解手术创伤引起的大脑神经功能的损伤。

| [1] | Hu D, Flick RP, Zaccariello MJ, et al. Association between Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia and Learning and Behavioral Outcomes in a Population-based Birth Cohort[J]. Anesthesiology, 2017, 127(2): 227-40. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001735. |

| [2] | Lei SY, Hache M, Loepke AW. Clinical research into anesthetic neurotoxicity:does anesthesia cause neurological abnormalities in humans[J]. J NeurosurgAnesthesiol, 2014, 26(4): 349-57. |

| [3] | Ing C, Dimaggio C, Whitehouse A, et al. Long-term differences in language and cognitive function after childhood exposure to anesthesia[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 130(3): e476-85. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-3822. |

| [4] | Backeljauw B, Holland SK, Altaye M, et al. Cognition and brain structure following early childhood surgery with anesthesia[J]. Pediatrics, 2015, 136(1): e1-12. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-3526. |

| [5] | Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association between a single general anesthesia exposure before age 36 months and neurocognitive outcomes in later childhood[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(21): 2312-20. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.6967. |

| [6] | Cattano D, Young C, Straiko MM, et al. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain[J]. AnesthAnalg, 2008, 106(6): 1712-4. |

| [7] | Yu D, Jiang Y, Gao J, et al. Repeated exposure to propofol potentiates neuroapoptosis and long-term behavioral deficits in neonatal rats[J]. NeurosciLett, 2013, 534(1): 41-6. |

| [8] | Nyman Y, Fredriksson A, Lonnqvist PA, et al. Etomidate exposure in early infant mice (P10) does not induce apoptosis or affect behaviour[J]. ActaAnaesthesiolScand, 2016, 60(5): 588-96. |

| [9] | Huang YY, Kandel ER, Varshavsky L, et al. A genetic test of the effects of mutations in PKA on mossy fiber LTP and its relation to spatial and contextual learning[J]. Cell, 1995, 83(7): 1211-22. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90146-9. |

| [10] | FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA review results in new warnings about using general anesthetics and sedation drugs in young children and pregnant women[EB/OL]. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532356.htm, 2017-04-28/2017-11-07 |

| [11] | Cao YL, Zhang W, Ai YQ, et al. Effect of propofol and ketamine anesthesia on cognitive function and immune function in young rats[J]. Asian Pac J Trop Med, 2014, 7(5): 407-11. DOI: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60066-3. |

| [12] | Workman AD, Charvet CJ, Clancy B, et al. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species[J]. J Neurosci, 2013, 33(17): 7368-83. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. |

| [13] | Cao XZ, Ma H, Wang JK, et al. Postoperative cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation in the hippocampus triggered by surgical trauma are exacerbated in aged rats[J]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2010, 34(8): 1426-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.027. |

| [14] | He HJ, Wang Y, Le Y, et al. Surgery upregulates high mobility group box-1 and disrupts the blood-brain barrier causing cognitive dysfunction in aged rats[J]. CNS NeurosciTher, 2012, 18(12): 994-1002. |

| [15] | Rosczyk HA, Sparkman NL, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation and cognitive function in aged mice following minor surgery[J]. Exp Gerontol, 2008, 43(9): 840-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.06.004. |

| [16] | Yirmiya R, Goshen I. Immune modulation of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2011, 25(2): 181-213. |

| [17] | Wuri G, Wang DX, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of surgical stress on longterm memory function in mice of different ages[J]. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 2011, 55(4): 474-85. DOI: 10.1111/aas.2011.55.issue-4. |

| [18] | Tan WF, Cao XZ, Wang JK, et al. Protective effects of lithium treatment for spatial memory deficits induced by tau hyperphosphorylation in splenectomized rats[J]. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 2010, 37(10): 1010-5. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05433.x. |

| [19] | Fidalgo AR, Cibelli M, White JP, et al. Peripheral orthopaedic surgery down-regulates hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor and impairs remote memory in mouse[J]. Neuroscience, 2011, 190(36): 194-9. |

| [20] | Fidalgo AR, Cibelli M, White JP, et al. Systemic inflammation enhances surgery-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice[J]. NeurosciLett, 2011, 498(1): 63-6. |

| [21] | Terrando N, Monaco C, Ma D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha triggers a cytokine cascade yielding postoperative cognitive decline[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(47): 20518-22. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1014557107. |

| [22] | Gao YJ, Ji RR. c-Fos and pERK, which is a better marker for neuronal activation and central sensitization after noxious stimulation and tissue injury[J]. Open Pain J, 2009, 2(1): 11-7. |

| [23] | Vareli K, Frangou-Lazaridis M. Prothymosin α is localized in mitotic spindle during mitosis[J]. Biol Cell, 2004, 96(6): 421-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.04.002. |

| [24] | 姚星, 彭勉, 鲁胜强, 等. 手术创伤对老龄大鼠海马炎症介质表达的影响[J]. 武汉大学学报:医学版, 2013, 34(2): 171-3. |

| [25] | 童民锋, 刘伟国. c-fos基因在大鼠创伤性颅脑损伤中不同阶段表达水平与细胞凋亡关系的研究[J]. 浙江创伤外科, 2009, 14(5): 432-3. |

| [26] | Li J, Han B, Ma X, et al. The effects of propofol on hippocampal caspase-3 and Bcl-2 expression following forebrain ischemiareperfusion in rats[J]. Brain Res, 2010, 1356(3): 11-23. |

| [27] | 任晓玲, 桂军云, 李海波, 等. 大鼠颅脑损伤急性期脑组织NF-κB、TNF-α的表达及丙泊酚的干预效应[J]. 现代医药卫生, 2011, 27(9): 1283-4. |

| [28] | Fredriksson A, Ponten ET, Eriksson P. Neonatal exposure to a combination of N-methyl-D-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor anesthetic agents potentiates apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent behavioral deficits[J]. Anesthesiology, 2007, 107(3): 427-36. DOI: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278892.62305.9c. |

| [29] | Sturman DA, Moghaddam B. The Neurobiology of Adolescence:Changes in brain architecture, functional dynamics, and behavioral tendencies[J]. NeurosciBiobehav Rev, 2011, 35(8): 1704-12. |

2018, Vol. 38

2018, Vol. 38