临床上对所有患者在全麻诱导前均常规进行预给氧,即诱导前为患者提供高浓度氧气(常规为纯氧),通过呼吸运动将其呼吸道内的氮气置换出来,增加血液和肺泡中的氧储备,从而获得足够的时间以完成气管插管,这是传统全麻诱导的必须步骤[1-2]。此方法可为心肺功能正常的患者提供大概7 min的无通气安全时限,即无通气状态下脉搏氧饱和度(SpO2)大于90%的持续时间[3]。目前大量研究表明,大部分气管插管可在40 s内完成[4-8]。随着现代插管技术的进步,气管插管时长甚至可缩短至10 s左右[9-10]。即使面对困难气道患者,仍可在20 s左右完成插管[11]。另外,吸入高浓度氧被证实与氧化应激、冠状动脉痉挛和肺不张等并发症相关[3, 12-14]。而在小鼠或人体上的研究证实,吸入空气时,以上并发症的严重程度显著降低[15-20]。故我们推测,空气面罩通气条件下行全麻诱导对于减轻或者预防以上并发症有一定的益处。同时,在插管技术不断娴熟、插管时长不断缩短的条件下,是否有必要对所有患者均常规进行预给氧值得商榷。

评价空气面罩通气条件下行全麻诱导插管可行性及安全性的关键在于,它能否为麻醉医师提供充足的无通气安全时限来完成气管插管,而其相关研究目前尚未见报道。本研究通过比较常规预给氧和空气面罩通气在无通气安全时限和气管插管时长方面的差异,来确定空气面罩通气情况下进行全麻诱导插管的可行性及安全性。

1 资料和方法 1.1 病例和分组80例拟全麻下行择期手术患者,年龄18~60岁,美国麻醉医师学会(ASA)分级Ⅰ ~Ⅱ级,体质量指数(BMI)18~30 kg/m2。排除的病例包括:预计插管困难者、血色素 < 90 g/L、吸空气时SpO2 < 95%、严重心肺疾病者、返流误吸风险高者、欠配合者、屏气时长 < 30 s者。预计插管困难预计插管困难的因素包括:病史、肥胖、颈短、甲颏间距 < 6.5 cm、张口度 < 2.5 cm、Mallampati分级>Ⅲ级等等常规判断方法[1]。所有患者均签署知情同意书。本研究获中山大学附属第六医院伦理委员会批准并在https://clinicaltrials.gov注册(NCT03239678)。

本研究采用随机设计,将患者按入组的先后顺序进行编号(1~80),用SPSS 22.0统计软件在计算机上产生与患者编号对应的随机数字,然后将随机数字按升序排序, 将排在第1~40位置上的随机数字所对应的患者分入Ⅰ组(预给氧),将第41~80位置上的随机数字所对应的患者分入Ⅱ组(空气面罩通气),每组各例40例。本研究采用双盲设计,患者和负责气管插管的医师均不知患者所在的组别。对于麻醉诱导期间吸入气体氧浓度的调节、SpO2及相关指标的记录则由助手来完成。

1.2 麻醉方法患者术前禁食6 h,禁饮2 h,麻醉前30 min肌注苯巴比妥钠0.1 g,阿托品0.5 mg。入室后执行标准监测,开放前臂静脉后,静滴乳酸林格氏溶液200 mL,以防止全麻诱导后低血压的发生。用2%利多卡因局麻下行左桡动脉穿刺置管以持续监测血压。脉搏氧饱和度监测仪监测SpO2,监测仪的探头夹在无血压袖带的那侧肢体的手指,并将其声音关闭,以防其气管插管的医师通过监测仪声音的变化来判断氧饱和度的大概数值。记录平卧位静息5 min时患者的基础SpO2,然后用密闭性良好的面罩给患者吸入按分组指定的气体。Ⅰ组吸氧浓度为100%,Ⅱ组为21%,气体流量6 L/min。首先要求患者用1 min的时间进行8次深呼吸,随后行全麻诱导。

诱导方案:静注咪达唑仑2 mg,紧接着丙泊酚1 mg/(kg·min)静脉泵注,芬太尼4 μg/kg用90 s的时间静脉泵注。每10 s进行1次改良观察者镇静/警觉评分(MOAA/S)[21],至患者对推动无反应(MOAA/S 1分),将丙泊酚药量改为维持量1 mg/(kg·min),并根据血压的情况给予调整。此时静注顺式阿曲库铵0.3 mg/kg并托起下颌,压紧面罩,确保不漏气,开始机控辅助呼吸(潮气量10 mL/kg,通气频率16次/min)。顺式阿曲库铵注射4 min后停止通气,进行气管插管,并记录喉镜下Cormack-Lehane分级(Ⅲ级和Ⅳ级提示有气管插管困难)[22]。全部气管插管由两位经过正规培训的有5年以上工作经验的麻醉医师执行,且统一使用Macintosh喉镜经口气管插管(镜片型号:Mac3;导管型号:男性患者7.5#,女性患者7.0#)。插管完成后,给套囊充气,但不予机械通气,用纤维支气管镜确认气管导管在患者的气管内。若面罩通气过程中SpO2降至90%以下,则立即改用纯氧面罩加压通气;或插管过程中SpO2降至90%以下,则尽快完成气管插管,并进行纯氧机械通气,以纠正低氧血症;若出现不能尽快完成气管插管的情况,则改用再次面罩通气,若通气效果欠佳,则考虑使用喉罩通气、环甲膜穿刺通气等。上述3种情况均认为是失败病例。

气管插管完成并经纤维支气管镜确认气管导管在气管内后,等待SpO2降至90%,此时将气管导管连接麻醉机,行机控通气(潮气量10 mL/kg,通气频率16次/min,吸氧浓度为40%)。SpO2回升至96%后,为防止过度通气,潮气量改为6~8 mL/kg,通气频率改为12次/min。

1.3 观察指标患者的一般资料:性别,年龄,身高,体质量等;无通气安全时限,即从停止面罩通气起到SpO2降至90%时所用的时间[3];气管插管时长,即从停止面罩通气起到气管插管后给套囊充气完毕所用的时间;两组患者在气管插管完成时,SpO2≥90%的例数;基础SpO2值、气管插管完成时SpO2值、气管导管连接麻醉机后SpO2回升至96%所用的时间和期间的最低SpO2值;面罩通气结束时和导管连接麻醉机时的呼气末二氧化碳分压(Pet CO2)。

1.4 统计学处理所有研究数据均采用SPSS 22.0统计学软件进行统计分析,计量资料以均数±标准差表示,并采用t检验。计数资料用卡方检验进行分析。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果入组的80例患者中,Ⅱ组有2例患者被剔除,1例在使用肌松药之前出现舌根后坠而给予纯氧,另1例因助手对数据记录不全而剔除。

2.1 两组一般资料比较两组患者在年龄、性别构成、血红蛋白量、体质量指数、ASA分级和Mallampati分级等一般资料的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表 1)。

| 表 1 两组患者的一般资料 Table 1 Demographic data of the patients in the two groups (Mean±SD or number of cases) |

在气管插管完成时,Ⅱ组40例患者除剔除的2例外,全部38例的SpO2≥90%;而Ⅰ组全部40例患者的SpO2≥90%。故两组患者在插管完成时SpO2≥90%的例数差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表 2)。

| 表 2 气管插管完成时脉搏氧饱和度≥90%的例数、无通气安全时限、气管插管时长、脉搏氧饱和度和呼气末二氧化碳分压等数值 Table 2 Number of cases with SpO2≥90% upon completion of tracheal incubation, peripheral oxygen saturation, partial pressure of end-tidal CO2, intubation time and safe duration of apnea in the two groups (Mean±SD or number of cases) |

两组的气管插管时长的差异无统计学意义(P> 0.05,表 2)。

2.4 两组无通气安全时限的比较无通气安全时限:Ⅱ组无通气安全时限显著小于Ⅰ组(P < 0.01,表 2);Ⅱ组无通气安全时限和BMI显著相关(P < 0.05,表 3);和年龄、性别、血红蛋白量、屏气时长以及是否抽烟无关(P>0.05,表 3)。

| 表 3 Ⅱ组患者无通气安全时限的影响因素分析 Table 3 Contributing factors for safe duration of apnea in patients without preoxygenatoin (Mean±SD, n=38) |

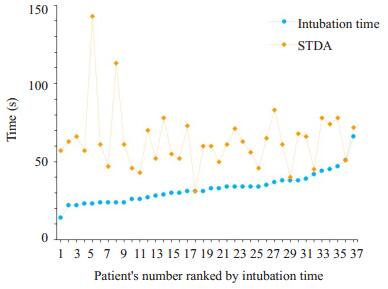

两组的无通气安全时限均显著大于气管插管时长(P < 0.01,表 4、图 1)。

| 表 4 每组患者无通气安全时限和气管插管时长的比较 Table 4 Intubation time and safe duration of apnea in the two groups (Mean±SD) |

|

图 1 Ⅱ组患者无通气安全时限和气管插管时长的分布 Figure 1 Safe duration of apnea and intubation time in patients without preoxygenatoin (n=38). STDA: Safe time duration for apnea. |

两组间基础SpO2值、气管导管连接麻醉机后SpO2回升至96%所用的时间以及面罩通气结束时PetCO2值的差异均无统计学意义;Ⅱ组气管插管完成时SpO2值、气管导管连接麻醉机后SpO2回升至96%期间的最低SpO2值和导管连接麻醉机时的PetCO2值均小于Ⅰ组(P < 0.01,表 2)。

3 讨论在全麻醉诱导前,麻醉医师常规对所有患者用高浓度氧气进行预给氧,此经典方法又称为“给氧去氮”,已在临床上使用了半个多世纪[23]。近年来,越来越多的证据表明,吸入高浓度氧气可引起各种不良后果。与0.4的吸入氧气分数(FiO2)相比,0.8 FiO2可显著降低氧合指数、抑制机体抗氧化应激反应,并增加乳酸水平和氧化应激水平[13]。将哺乳类动物细胞暴露于高浓度氧气的环境后,细胞内活性氧簇水平提高,并抑制了细胞的抗氧化应激和系统修复的能力。吸入高浓度氧还可导致冠状动脉痉挛[24]。将7位健康成人在吸空气时和吸5 min纯氧后的冠状动脉超声结果作对比,发现吸纯氧后,受试者的冠状动脉的血管阻力增加了(20±4)%,血流速度降低了(15±3)%[20]。另外研究表明,分别用0.6 FiO2、0.8 FiO2和纯氧给不同患者吸氧5.5 min,然后行气管插管并用0.4 FiO2维持机械通气9 min,患者便可出现不同程度的肺不张;预给氧时的FiO2越大,肺不张的程度越高[3]。然而,吸氧时间超过14 min后,与纯氧相比,0.8 FiO2预给氧在降低肺不张程度方面的优势会逐渐消失[25]。

综上所述,目前临床上常规的预给氧可通过氧化应激、冠状动脉痉挛和肺不张等途径对全麻患者造成各种不良后果。本研究首次证实了在空气面罩通气的情况下,全麻诱导的无通气安全时限达63.6±20.0 s,可为有经验的麻醉医师提供较充足的时间顺利完成气管插管。

本研究发现,当患者在空气面罩通气条件下(FiO2= 0.21)行全麻诱导插管时,其无通气安全时限要显著低于预给氧条件下插管的患者(P < 0.01)。此结果与Edmark等[3]的发现相似。本研究发现,空气面罩通气条件下行全麻诱导后,无通气安全时限的数值与患者的年龄、性别、血红蛋白量、屏气时长以及是否抽烟无关,但与BMI的数值显著相关。BMI≥25患者的无通气安全时限显著小于体质量正常的患者。Jense等[26]也证实,超重或肥胖患者与体质量正常的患者相比,在无通气期间更容易发生低氧血症。其原因可能与此类患者的肺部功能相对异常有关,包括肺活量、最大吸气量、补呼气量、功能残气量和呼吸系统顺应性的降低[27]。

本研究中,两组的气管插管时长的差异无统计学意义。除剔除的2例外,剩余78例患者插管时长为32.8± 9.6 s,与其他研究的结果相似[5, 8]。一些非传统插管器械(如光棒、可视喉镜等)在缩短插管时长方面展现了明显的优势,包括对困难气道患者的插管或者是由非麻醉专业的医师进行的插管[11, 28]。在一项包含265例患者的使用光棒行气管插管的研究中,206例患者有困难插管病史或预测有困难插管可能,其插管时长为25.7±20.1 s;59例传统方法插管失败后改用光棒插管的患者,其插管时长为19.7±13.5 s [11]。对152例患者使用光棒插管,148例(97.4%)一次性插管成功,插管时长为11.5±6.7 s [9]。随着插管技术的不断发展,空气面罩通气情况下行全麻诱导的安全性和可行性有希望得到进一步的证实。本研究80例患者中,在气管插管完成时,Ⅱ组40例患者除剔除的2例外,全部38例的SpO2≥90%;而Ⅰ组全部40例患者的SpO2≥90%。故两组患者在插管完成时SpO2≥90%的例数没有具统计学意义的差异。

综上所述,和气管插管时长相比,空气面罩通气的全麻诱导可为有经验的麻醉医师提供较充足的无通气安全时限完成气管插管。

致谢: 感谢中山六院麻醉护士潘星宇、韩佳馨在数据记录方面所提供的帮助,感谢中山六院麻醉手术科全体医护对本研究的支持。| [1] | Carin A. Hagberg CAA. airway management in the adult, chapter 55. in miller rd, editors: miller's anesthesia[M]. Philadelphia, Elsevier, 2014: 1648-53. |

| [2] | 邓小明, 姚尚龙, 于布为, 等. 第4版[M]. 北京: 人民出版社, 2014: 1043-4. |

| [3] | Edmark L, Kostova-Aherdan K, Enlund M, et al. Optimal Oxygen concentration during induction of general anesthesia[J]. Anesthesiology, 2003, 98(1): 28-33. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-200301000-00008. |

| [4] | Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, et al. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016, 11: CD011136. |

| [5] | Arici S, Karaman S, Dogru S, et al. The McGrath series 5 video laryngoscope versus the macintosh laryngoscope: a randomized trial in obstetric patients[J]. Turkish J Med Sci, 2014, 44(3): 387-92. |

| [6] | Aziz MF, Dillman D, Fu RW, et al. Comparative effectiveness of the C-MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy in the setting of the predicted difficult airway[J]. Anesthesiology, 2012, 116(3): 629-36. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318246ea34. |

| [7] | Sun DA, Warriner CB, Parsons DG, et al. The GlideScope video laryngoscope: randomized clinical trial in 200 patients[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2005, 94(3): 381-4. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aei041. |

| [8] | Wallace CD, Foulds LT, Mcleod GA, et al. A comparison of the ease of tracheal intubation using a McGrath Mac(R) laryngoscope and a standard Macintosh laryngoscope[J]. Anaesthesia, 2015, 70(11): 1281-5. DOI: 10.1111/anae.13209. |

| [9] | Kim J, Im KS, Lee JM, et al. Relevance of radiological and clinical measurements in predicting difficult intubation using light wand (Surch-lite) in adult patients[J]. J Int Med Res, 2016, 44(1): 136-46. DOI: 10.1177/0300060515594193. |

| [10] | Pournajafian AR, Ghodraty MR, Faiz SH, et al. Comparing glidescope video laryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope regarding hemodynamic responses during orotracheal intubation:A randomized controlled trial[J]. Iran Red Crescent Med J, 2014, 16(4): e12334. |

| [11] | Hung OR, Pytka S, Morris I, et al. Lightwand intubation: Ⅱ--clinical trial of a new lightwand for tracheal intubation in patients with difficult airways[J]. Can J Anaesth, 1995, 42(9): 826-30. DOI: 10.1007/BF03011187. |

| [12] | Rothen H, Sporre B, Engberg G, et al. Prevention of atelectasis during general anaesthesia[J]. Lancet, 1995, 345(8962): 1387-91. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92595-3. |

| [13] | Koksal GM, Dikmen Y, Erbabacan E, et al. Hyperoxic oxidative stress during abdominal surgery: a randomized trial[J]. J Anesth, 2016, 30(4): 610-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00540-016-2164-7. |

| [14] | Moradkhan R, Sinoway LI. Revisiting the role of Oxygen therapy in cardiac patients[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010, 56(13): 1013-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.052. |

| [15] | Saric A, Sobocanec S, Safranko ZM, et al. Female headstart in resistance to hyperoxia-induced oxidative stress in mice[J]. Acta Biochim Pol, 2014, 61(4): 801-7. |

| [16] | Bouch S, O'reilly M, Harding R, et al. Neonatal exposure to mild hyperoxia causes persistent increases in oxidative stress and immune cells in the lungs of mice without altering lung structure[J]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015, 309(5): L488-96. DOI: 10.1152/ajplung.00359.2014. |

| [17] | Paiva LA, Silva IS, de Souza AS, et al. Pulmonary oxidative stress in diabetic rats exposed to hyperoxia[J]. Acta Cirurgica Brasileira, 2017, 32(7): 503-14. DOI: 10.1590/s0102-865020170070000001. |

| [18] | Borges JB, Hedenstierna G, Bergman JS, et al. First-time imaging of effects of inspired Oxygen concentration on regional lung volumes and breathing pattern during hypergravity[J]. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2015, 115(2): 353-63. DOI: 10.1007/s00421-014-3020-9. |

| [19] | Dussault C, Gontier E, Verret C, et al. Hyperoxia and hypergravity are Independent risk factors of atelectasis in healthy sitting humans: a pulmonary ultrasound and SPECT/CT study[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2016, 121(1): 66-77. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00085.2016. |

| [20] | Momen A, Mascarenhas V, Gahremanpour A, et al. Coronary blood flow responses to physiological stress in humans[J]. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2009, 296(3): H854-61. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.01075.2007. |

| [21] | Yuen VM, Irwin MG, Hui TW, et al. A double-blind, crossover assessment of the sedative and analgesic effects of intranasal dexmedetomidine[J]. Anesth Analg, 2007, 105(2): 374-80. DOI: 10.1213/01.ane.0000269488.06546.7c. |

| [22] | Selvi O, Kahraman T, Senturk O, et al. Evaluation of the reliability of preoperative descriptive airway assessment tests in prediction of the Cormack-Lehane score: A prospective randomized clinical study[J]. J Clin Anesth, 2017, 36(7): 21-6. |

| [23] | Hamilton WK, Eastwood DW. A study of denitrogenation with some inhalation anesthetic systems[J]. Anesthesiology, 1955, 16(6): 861-7. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-195511000-00004. |

| [24] | Baez A, Shiloach J. Effect of elevated Oxygen concentration on bacteria, yeasts, and cells propagated for production of biological compounds[J]. Microb Cell Fact, 2014, 13: 181. DOI: 10.1186/s12934-014-0181-5. |

| [25] | Edmark L, Auner U, Enlund M, et al. Oxygen concentration and characteristics of progressive atelectasis formation during anaesthesia[J]. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 2011, 55(1): 75-81. DOI: 10.1111/aas.2010.55.issue-1. |

| [26] | Jense HG, Dubin SA, Silverstein PI, et al. Effect of obesity on safe duration of apnea in anesthetized humans[J]. Anesth Analg, 1991, 72(1): 89-93. |

| [27] | Behazin N, Jones SB, Cohen RI, et al. Respiratory restriction and elevated pleural and esophageal pressures in morbid obesity[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2010, 108(1): 212-8. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91356.2008. |

| [28] | Hirabayashi Y, Seo N. Tracheal intubation by non-anesthesia residents using the Pentax-AWS airway scope and Macintosh laryngoscope[J]. J Clin Anesth, 2009, 21(4): 268-71. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.08.024. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37