2. 南方医科大学中医药学院,广东 广州 510515;

3. 广州中医药大学,广东 广州 510403

2. School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

3. Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou 510403, China

前交叉韧带(ACL)是膝关节中维持其稳定的重要韧带之一[1-2]。临床上,当ACL因为各种原因导致损伤或者断裂时,不仅会因为其物理结构受损导致膝关节不稳,而且还会因为损伤后本体感觉的缺失而进一步影响膝关节整体稳定性[3-6]。本体感觉是人体控制和协调肢体运动过程中不可或缺的组成部分,它的主要作用是提供一些关节运动和位置的传入信息,而机体正是通过整合这些信息来预防和避免因过度运动而导致的韧带损伤[7-9]。因此,ACL的本体感觉对于膝关节稳定性至关重要,一旦发生本体感觉缺失,应积极采取措施治疗。

电针疗法是一种将针灸和电刺激相结合的治疗方法,现代许多研究发现,通过针刺合并电刺激相应穴位,可以使局部肌肉关节功能得到一定程度的恢复[10-14]。研究发现电针可以改善软组织的微循环、消除炎症介质、抑制损害性信息的传导[15],另一方面可以通过增加本体感觉从而对骨关节损伤起到康复治疗作用[16]。在兔膝关节ACL损伤模型中本体感受器的数量会减少,并且体感诱发电位和腘绳肌肌电图的潜伏期逐渐延长、波幅逐渐降低[17],而电针对本体感觉功能的影响可能是通过针灸及电刺激增强关节周围的本体感受器及神经末梢兴奋性产生的[18]。但目前针对电针穴位治疗ACL本体感觉减退的基础研究甚少,对本体感觉的客观评价也很难实现。例如,通过电针刺激督脉,增强神经可塑性,促进轴突再生及突触重建[19]。通过电针治疗可以治疗坐骨神经损伤,维持感觉神经元存活,最终改善大鼠下肢的感觉功能[20]。以往文献多从分子生物学角度观察电针治疗本体感觉减退及神经损伤的效果,而本研究着重从神经电生理以及病理组织学方面观测ACL本体感觉变化,以及电针治疗的效果,使结果更具有直观性、客观性,以及临床指导价值。

因此,本研究通过电针穴位干预灵长类动物食蟹猴ACL损伤模型,并利用神经电生理学体感诱发电位(SEPs)和运动神经传导速度(MCV)检测,以及对ACL中本体感受器形态、总体数量和变异数量的观察,来探讨电针对食蟹猴单侧ACL损伤后本体感觉的影响,进一步揭示电针对ACL本体感觉减退的治疗机制。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要实验材料 1.1.1 实验动物选取SPF级正常食蟹猴21只,均为雄性,年龄4~5岁,体质量6~7 kg,由云南英茂生物科技有限公司提供。动物伦理通过了该公司的动物实验伦理审查委员会的审查,动物饲养及动物福利已通过国际实验动物饲养评估认证协会(AAALAC)认证执行。

1.1.2 仪器关节镜系统(型号:72200616,美国Smith & Nephew),穴位神经刺激仪(型号:G91-D,扬州康岭医用电子仪器有限公司),诱发电位仪(型号:MEB-9402C,日本光电公司),全自动真空组织脱水机(型号:ASP6025,德国Leica),全自动冷冻包埋机(型号:Arcadia,德国Leica),石蜡切片机(型号:819,德国Leica),烤片机(型号:MST,德国SLEE),倒置显微镜(型号:DMi8,德国Leica)。

1.1.3 试剂和耗材毫针(型号:0.3 mm×40 mm)购自中国苏州医疗用品厂有限公司,Zoletil 50麻醉剂购自法国Virbac,盐酸左氧氟沙星氯化钠注射液购自江苏豪森药业股份有限公司,注射用盐酸曲马多购自石家庄制药集团有限公司,碘伏消毒液、0.9% NaCl、清创器械包、一次性注射器、无菌纱布、可吸收缝合线、无菌手术单均购自北京中杉金桥生物技术有限公司,氯化金、乙醇、二甲苯、中性树胶、蒸馏水、无水酒精、天然浓缩柠檬汁、甲酸、甘油均购自广东光华科技股份有限公司。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 动物分组及造模将27只正常食蟹猴随机分为3组:电针干预组(n=9)、模型对照组(n=9)和正常对照组(n=9)。然后对电针干预组和模型对照组的食蟹猴进行单膝ACL损伤造模(造模侧随机选择),单膝ACL损伤模型采用关节镜微创造模技术,造模方法:用Zoletil 50麻醉剂肌注麻醉后,作膝关节关节镜入路切口,探查膝关节软骨、前后交叉韧带、半月板等均完好无损,用钩刀将ACL横行切断1/4,冲洗关节腔,缝合切口,术毕(图 1)。手术均由同一组操作人员完成。术后3 d分别给予每只造模食蟹猴盐酸左氧氟沙星氯化钠注射液(8 mg/kg)静脉滴注预防感染,同时给予注射用盐酸曲马多(2 mg/kg)肌注减轻术后疼痛。术后7 d所有动物的伤口均愈合,未发生感染或者延迟愈合等情况。

|

图 1 通过关节镜技术建立ACL损伤模型 Figure 1 Establishment of ACL injury model in cynomolgus monkeys with arthroscopic technique. A: Arthroscopic approach (arrow); B: Arthroscopic operation in the knee joint cavity; C: Normal ACL (arrow); D: 1/4 ACL injury induced using a hook knife. Arrow indicates the injured site in the ACL. |

正常对照组不做任何手术干预,只给予普通饲养适应性喂养,在实验开始时即进行神经电生理检测,以及处死取ACL进行氯化金染色,用于对比。

1.2.2 电针干预电针干预组在术后7 d伤口愈合后即开始电针干预,选取损伤侧的委阳(属足太阳膀胱经,位于腘横纹上,股二头肌腱的内侧缘)、阴谷(属足少阴肾经,位于腘窝内侧,当半腱肌肌腱与半腊肌肌腱之间)、膝阳关(属足少阳胆经,位于股骨外上髁上方的凹陷处)、曲泉(属足厥阴肝经,位于股骨内侧髁的后缘,半腱肌、半膜肌止端的前缘凹陷处),用指切进针法进针,进针后针尖略向内上倾斜,进针约0.5~0.8 cm,施以提插捻转,待腘绳肌有所抽动即可。采用穴位神经刺激仪行电针治疗,单侧4个穴位需要两组电针,委阳和阴谷一组(委阳接正极,阴谷接负极),膝阳关和曲泉一组(膝阳关接正极,曲泉接负极),频率20 Hz、强度3 mA(预实验中食蟹猴最佳耐受强度),每次20 min,每天治疗1次,4周为1个疗程,总共干预3个疗程(图 2)。空白模型组不给于任何干预。

|

图 2 电针干预膝关节周围穴位 Figure 2 Acupoints around the knee for electropuncture. A: Acupoint nerve stimulator; B: Acupuncture points on the injured side of the knee. |

在电针干预的4、8、12周时,分别在电针干预组和模型对照组选取3只食蟹猴,进行神经电生理检测,然后在处死食蟹猴并取其ACL进行氯化金染色。

1.2.3 神经电生理学检查SEPs:用Zoletil 50麻醉剂麻醉成功后,简单固定头部及四肢。两耳尖连线和鼻根部到枕外隆突连线的交点再往后1 cm(下肢皮层区)作为记录电极点,参考电极放置于鼻根部,地线接于侧耳鬓处。用双极表面电极刺激ACL的股骨或者胫骨附着部位对应体表处,刺激参数为恒压方法,在波宽0.1 ms,频率2 Hz,刺激强度15~20 mA的情况下测定SEPs。

MCV:将刺激电极置于腘窝处进行刺激,记录电极置于腘绳肌肌腹,参考电极放置于记录电极旁开2 cm。用双极表面电极刺激ACL的股骨或者胫骨附着部位对应体表处,刺激参数为恒压方法,在波宽0.2 ms,频率1 Hz,刺激强度25~30 mA的情况下测定MCV。使用诱发电位仪记录SEPs和MCV,引得的信号输入微机操作系统,测量和分析SEPs和MCV图形、潜伏期和波幅指标。

1.2.4 氯化金染色先将动物给予Zoletil 50麻醉剂麻醉后,静脉注射空气处死,快速暴露并取材ACL,将新鲜取下的标本放入柠檬汁和88%甲酸的混合液中(柠檬汁:甲酸=3: 1),置暗室中室温下放15 min→l%氯化金溶液置暗室中放30 min→25%甲酸溶液置暗室中保存15 h→蒸馏水冲洗1 h→纯甘油保存24 h→常规梯度酒精脱水→二甲苯透明→石蜡包埋切片。每个ACL只选取5张病理切片,选取的切片尽量代表性覆盖组织各个部位。标记股骨端、胫骨端和中间部,由3名操作者分别对ACL的本体感受器计数,避免重复记录。

1.3 统计学方法所有资料采用SPSS 20.0统计软件进行统计学分析。计量数据以均数±标准差表示,并应用重复测量的方差分析进行统计,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 神经电生理检测结果在4、8、12周中的任何一个时间点,与正常对照组相比,电针干预组和模型对照组的SEPs、MCV潜伏期延长,波幅下降,但电针干预组优于模型对照组,3组差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。

在模型对照组中,SEPs、MCV随时间增加而潜伏期逐渐延长,波幅逐渐下降,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),而在电针干预组中,SEPs、MCV随时间增加而潜伏期逐渐缩短,波幅逐渐上升,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 3~6)。

|

图 3 3组SEPs潜伏期在不同时间点的对比 Figure 3 Comparison of the incubation time of SEPs in the 3 groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

|

图 4 3组SEPs波幅在不同时间点的对比 Figure 4 Comparison of amplitude of SEPs in the groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

|

图 5 3组MCV潜伏期在不同时间点的对比 Figure 5 Comparison of incubation of MCV in the 3 groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

|

图 6 3组MCV波幅在不同时间点的对比 Figure 6 Comparison of the amplitude of the MCV in the 3 groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

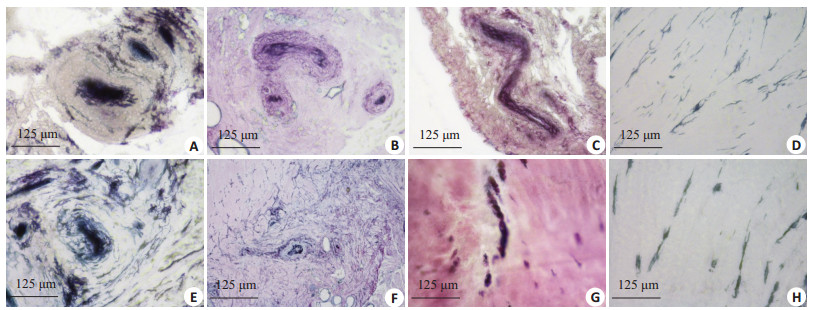

通过氯化金染色,我们在ACL中共观察到四类本体感受器,分别是:Ruffini小体、Pacinian小体、Golgi腱器官和游离神经末梢,正常的Ruffini小体形态类似于树形,可见有分支状结构出现;Pacinian小体一般为椭圆形,外层有一层被囊包裹;Golgi腱器官呈螺旋状形态出现;而游离神经末梢一般无特定的形态,多呈细长的梭形。本体感受器受损异常变形后,结构出现溶解、紊乱、变形,甚至体积缩小,而游离神经末梢多呈不规则形态,一般可见神经末梢明显减少(图 7)。

|

图 7 正常和异常变异的本体感受器对比 Figure 7 Comparison of normal and variable proprioceptors (Original magnification: × 400). A, B, C, D: Ruffini corpuscle, Pacinian corpuscle, Golgi tendon organs and free nerve endings in the normal ACL, respectively; E, F, G: Variable Ruffini corpuscle, Pacinian corpuscle and Golgi tendon organs in the injured ACL, respectively; H: Free nerve endings in the injured ACL, where the number of the nerve endings became less. |

在本体感受器总体数量上,在4、8、12周中的任何一个时间点,与正常对照组相比,电针干预组和模型对照组下降,差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05),且模型对照组趋势比电针干预组明显,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05);在本体感受器变异数量上,在4、8、12周中的任何一个时间点,与正常对照组相比,电针干预组和模型对照组均上升,有统计学差异(P < 0.05),但电针干预组与模型对照组比较,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。在电针干预组和模型对照组中,本体感受器随时间增加而总体数量下降,变异数量上升,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 8,9)。

|

图 8 3组本体感受器的总数在不同时间点的对比 Figure 8 Comparison of total number of proprioceptors in the 3 groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

|

图 9 3组本体感受器的变异数在不同时间点的对比 Figure 9 Comparison of variable proprioceptors in the 3 groups at different time points. aP < 0.05 vs 8 weeks in the same group; bP < 0.05 vs 12 weeks in the same group; cP < 0.05 vs the model group at the same time; dP < 0.05 vs the blank control group. |

膝关节是人体最大结构并且最复杂的屈曲关节,运动损伤、车祸伤、外来暴力等诸多因素可以造成膝关节的损伤[21-24]。膝关节损伤作为临床上的常见疾病,其损伤的类型较多,具体包括:膝关节骨折、膝关节骨挫伤、关节软骨损伤、韧带损伤和半月板损伤等,其中尤以ACL损伤多见[25-28]。临床上,当ACL断裂损伤时,即使韧带获得重建,患者仍会出现膝关节不稳,这可能和本体感觉的缺失有关。本体感觉主要依靠分布在肌肉、关节等处的本体感受器来感知的位置觉、运动觉和振动觉,而ACL作为稳定膝关节前向运动的主要韧带,其稳定作用的发挥很大程度上依赖于其中本体感受器的功能作用[29-32]。

早在1956年,Skoglund等[32]就已发现ACL中的本体感受器。Schultz等[33]又将其分为4类:Ruffini小体、Pacinian小体、Golgi腱器官和其它游离神经末梢,ACL中的Pacinian小体可以感知膝关节运动的起始、加速和终止。Ruffini小体和Golgi腱器官对关节内压力、韧带张力变化能作出反应,因此,能感受膝关节的位置和旋转角度。ACL中的游离神经末梢参与感受细小刺激。本体感受器主要集中分布在ACL的腱骨愈着部,当ACL受到应力时,愈合部的本体感受器就会感知到,并发出信号使大脑作出反应,从而保护膝关节稳定性。另外,如果当ACL损伤时,其中的本体感受器必然也会受损,从而导致功能减退,影响膝关节的位置觉、运动觉和振动觉,即使给予韧带重建也无法到达本体感觉的完全恢复。因此,ACL除了通过其本身的物理特性来稳定膝关节以外,本体感觉也在维持膝关节稳定性中有着重要意义[34-35]。在本研究的模型对照组中,SEPs、MCV随时间增加而潜伏期逐渐延长,波幅逐渐下降,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),同时本体感受器总体数量下降,变异数量上升,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),这说明当ACL损伤时,本体感觉会受到影响。

3.2 电针对于ACL本体感觉的促进作用许多研究都已证实电针刺激穴位疗法在治疗肢体活动障碍、关节疼痛、药物依赖等方面具有确切的疗效[36-38]。针刺效应主要由中枢神经系统介导,即针刺能够促进中枢系统内的内源性阿片肽及单胺类神经递质的释放,引起特定生理学效应而达到治疗的目的。电针可促使神经元生长、轴突再生、突触重构以及靶器官功能联系得到改善[39]。本研究选取委阳、阴谷、膝阳关及曲泉这几个穴位,主要的依据是:ACL损伤属中医筋伤痹证之范畴,以肝脾肾虚为根本,风寒湿外邪侵袭为外因。我们选取的穴位中,委阳,属足太阳膀胱经,为三焦下合穴,主治腰脊强痛,腿足挛痛;阴谷,属足少阴肾经穴位,主治膝关节疼痛不利;膝阳关,属足少阳胆经,主治膝腘肿痛、挛急及小腿麻木等下肢、膝关节疾患;曲泉,属足厥阴肝经,主治膝髌肿痛,下肢痿痹。故而在膝关节的局部选取这几个穴位,利用穴位的近治作用,很好的顾及到对诸经的调整[40-41]。电针可通过刺激相关穴位,向中枢传入大量的本体运动和感觉信息,从而帮助建立正常的感觉、运动模式,反射性激活屈、伸肌群而参与稳定膝关节活动,重建关节本体感觉的功能[42]。在本研究中,电针干预组的SEPs、MCV随时间增加而潜伏期逐渐缩短,波幅逐渐上升,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),同时,电针干预可以延缓总体数量的下降趋势,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。这说明电针对本体感觉有一定的促进作用。在本体感受器变异数量上,电针干预组与模型对照组比较,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),这说明电针对已经变异的本体感受器没有可逆效果。

综上所述,ACL本体感觉在膝关节稳定中有着重要的作用。ACL损伤后,同侧ACL的SEPs、MCV随时间增加而潜伏期逐渐延长,波幅逐渐下降,同时,本体感受器总体数量下降,变异数量上升,这说明损伤ACL的本体感觉随时间增加而逐渐下降,而电针干预治疗是一种有效的干预方法,可以对损伤ACL的本体感觉起到一定的康复治疗作用。

| [1] | Noyes FR, Huser LE, Levy MS. Rotational knee instability in ACL-Deficient knees: role of the anterolateral ligament and iliotibial band as defined by tibiofemoral compartment translations and rotations[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2017, 99(4): 305-14. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00199. |

| [2] | Parcells BW, Tria AJ. The cruciate ligaments in total knee arthroplasty[J]. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ), 2016, 45(4): E153-60. |

| [3] | 高彦平, 姜雪梅, 张鸣生. 前交叉韧带胫骨棘止点撕脱骨折损伤机制及诊治[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2008, 28(11): 2086-8. DOI: 10.3321/j.issn:1673-4254.2008.11.047. |

| [4] | Lowe WR, Warth RJ, Davis EP, et al. Functional bracing after anterior cruciate ligament Reconstruction: a systematic review[J]. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2017, 25(3): 239-49. DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00710. |

| [5] | Li J, Kong F, Gao X, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of knee stability and proprioception for posterior cruciate ligament Reconstruction with autograft, hybrid graft, and γ-Irradiated allograft[J]. Arthroscopy, 2016, 32(12): 2548-55. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.04.024. |

| [6] | Mir SM, Talebian S, Naseri N, et al. Assessment of knee proprioception in the anterior cruciate ligament injury risk position in healthy subjects: a cross-sectional study[J]. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26(10): 1515-8. DOI: 10.1589/jpts.26.1515. |

| [7] | Yeung J, Cleves A, Griffiths H, et al. Mobility, proprioception, strength and FMS as predictors of injury in professional footballers[J]. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med, 2016, 2(1): e000134. DOI: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000134. |

| [8] | Long Z, Wang R, Han J, et al. Optimizing ankle performance when taped: Effects of kinesiology and athletic taping on proprioception in full weight-bearing stance[J]. J Sci Med Sport, 2017, 20(3): 236-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.024. |

| [9] | Torres R, Ferreira J, Silva D, et al. Impact of patellar tendinopathy on knee proprioception: a Cross-Sectional study[J]. Clin J Sport Med, 2017, 27(1): 31-6. DOI: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000295. |

| [10] | Ye T, Xue HW, Wang Y, et al. Controlled observation on the efficacy of thoracic facet joint disorder treated with electroacupuncture and manual reduction[J]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu, 2013, 33(12): 1077-80. |

| [11] | Kwon YD, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2006, 45(11): 1331-7. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel207. |

| [12] | 董宝强, 赵宗仙, 宋杰, 等. 膝骨性关节炎经筋病灶点体表温度分布规律分析[J]. 中华中医药杂志, 2014, 29(9): 2757-60. |

| [13] | 蔡敬宙, 邓加勤, 李湘力, 等. 膝关节隔盐灸治疗膝关节骨关节炎临床疗效观察[J]. 辽宁中医药大学学报, 2015, 17(7): 157-60. |

| [14] | 曹锐, 杨红玲, 何润东. 针刺治疗膝骨性关节炎45例临床观察[J]. 中医杂志, 2016, 57(13): 1133-6. |

| [15] | 王傅, 陈丽珍, 雷振辉, 等. 电针综合疗法治疗髌骨软化症的疗效观察[J]. 中国康复医学杂志, 2007, 22(1): 8. |

| [16] | 郭纪涛, 戴琪萍, 裘敏蕾, 等. 电针对膝骨关节炎患者本体感觉影响的· 1176 · J South Med Univ, 2017, 37(9): 1171-1177 http://www.j-smu.com临床观察[J]. 中国康复医学杂志, 2008, 23(12): 1114-6. |

| [17] | 李彬, 吴海山, 温昱. 兔膝关节ACL损伤后韧带内本体感受器的变化及机制[J]. 山东医药, 2011, 51(31): 16-8. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2011.31.009. |

| [18] | 朱燕, 裘敏蕾, 丁莹, 等. 电针对功能性踝关节不稳运动员本体感觉的影响[J]. 世界针灸杂志:英文版, 2013, 23(1): 4-8. |

| [19] | 李兵奎, 曾彬, 常巍, 等. 督脉电针对脊髓损伤大鼠生长相关蛋白43表达的影响[J]. 中国康复理论与实践, 2014, 20(1): 27-9. |

| [20] | 潘墦, 于天源, 吴剑聪, 等. 电针对坐骨神经损伤大鼠背根神经节中神经营养因子-3及其受体TrkC的影响[J]. 中国康复医学杂志, 2014, 29(12): 1109-12. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2014.12.002. |

| [21] | Wang X, Wei L, Lv Z, et al. Proximal fibular osteotomy: a new surgery for pain relief and improvement of joint function in patients with knee osteoarthritis[J]. J Int Med Res, 2017, 45(1): 282-9. DOI: 10.1177/0300060516676630. |

| [22] | Patel RM, Brophy RH. Anterolateral ligament of the knee: anatomy, function, imaging, and treatment[J]. Am J Sports Med, 2017, 3: 363546517695802. |

| [23] | Chen XX, Li J, Wang T, et al. Anatomical knee variants in discoid lateral meniscal tears[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2017, 130(5): 536-41. DOI: 10.4103/0366-6999.200535. |

| [24] | 彭炳龙, 贾芝和, 文姗, 等. 改良膝关节侧方小切口治疗胫骨平台骨折[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2010, 30(11): 2568-9. |

| [25] | Leppanen M, Pasanen K, Kujala UM, et al. Stiff landings are associated with increased ACL injury risk in young female basketball and floorball players: response[J]. Am J Sports Med, 2017, 45(3): NP5-6. |

| [26] | Bojicic KM, Beaulieu ML, Imaizumi Krieger DY, et al. Association between lateral posterior tibial slope, body mass index, and ACL injury risk[J]. Orthop J Sports Med, 2017, 5(2): 2325967116688664. |

| [27] | Bisciotti GN, Chamari K, Cena E, et al. ACL injury in football: a literature overview of the prevention programs[J]. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J, 2017, 6(4): 473-9. |

| [28] | 张力, 靳安民, 李奇. rhBMP-2增强前交叉韧带重建术后腱骨界面愈合能力的实验研究[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2008, 28(10): 1869-73. DOI: 10.3321/j.issn:1673-4254.2008.10.024. |

| [29] | Reis Eda F, Pereira GB, de Sousa NM, et al. Acute effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and static stretching on maximal voluntary contraction and muscle electromyographical activity in indoor soccer players[J]. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2013, 33(6): 418-22. |

| [30] | Godinho P, Nicoliche E, Cossich V, et al. Proprioceptive deficit in patients with complete tearing of the anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Rev Bras Ortop, 2015, 49(6): 613-8. |

| [31] | Relph N, Herrington L, Tyson S. The effects ofACL injury on knee proprioception: a meta-analysis[J]. Physiotherapy, 2014, 100(3): 187-95. DOI: 10.1016/j.physio.2013.11.002. |

| [32] | Skoglund S. Anatomical and physiological studies of knee joint innervation in the cat[J]. Acta Physiol Scand, 1956, 36(124): 1-101. |

| [33] | Schultz RA, Miller DC, Kerr CS, et al. Mechanoreceptors in human cruciate ligaments. A histological study[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1984, 66(7): 1072-6. DOI: 10.2106/00004623-198466070-00014. |

| [34] | Lee SJ, Ren Y, Chang AH, et al. Effects of pivoting neuromuscular training on pivoting control and proprioception[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2014, 46(7): 1400-9. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000249. |

| [35] | Braunig P, Hustert R. Proprioceptive control of a muscle receptor organ in the locust leg[J]. Brain Res, 1983, 274(2): 341-3. DOI: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90715-1. |

| [36] | Baert IA, Mahmoudian A, Nieuwenhuys A, et al. Proprioceptive accuracy in women with early and established knee osteoarthritis and its relation to functional ability, postural control, and muscle strength[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2013, 32(9): 1365-74. DOI: 10.1007/s10067-013-2285-4. |

| [37] | Gao YH, Li CW, Wang JY, et al. Activation of hippocampal MEK1 contributes to the cumulative antinociceptive effect of electroacupuncture in neuropathic pain rats[J]. BMC Complement AlternMed, 2016, 16(1): 517. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-016-1508-z. |

| [38] | Huang KY, Liang S, Yu ML, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture for improving learning and memory ability in animals[J]. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2016, 16(1): 297. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-016-1298-3. |

| [39] | Villarreal Santiago M, Tumilty S, M.cznik A, et al. Does acupuncture alter pain-related functional connectivity of the central nervous system? a systematic review[J]. J Acupunct Meridian Stud, 2016, 9(4): 167-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.jams.2015.11.038. |

| [40] | 李学武, 赵吉平, 汤立新, 等. 透针法治疗膝关节骨性关节炎的临床疗效评价[J]. 北京中医药大学学报, 2006, 29(12): 844-6. DOI: 10.3321/j.issn:1006-2157.2006.12.014. |

| [41] | 刘晴, 刘维, 吴沅皞. 针灸治疗膝关节骨性关节炎选穴规律现代文献研究[J]. 山东中医杂志, 2015, 34(11): 824-6. |

| [42] | Zhu Y, Qiu ML, Ding Y, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on the proprioception of athletes with functional ankle instability[J]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu, 2012, 32(6): 503-6. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37