风湿热引起的风湿性心脏病会导致心脏瓣膜的永久性损伤,这在发达国家虽然不常见,但仍然是全世界发展中国家的重大健康问题[1]。随着生活及医疗条件的改善,风湿性心脏病的人群患病率正在降低,但我国瓣膜性心脏病仍以风湿性心脏病最为常见[2-4]。风湿性心脏瓣膜病最终导致心脏扩大、心衰、心律失常危及生命。风湿性瓣膜病的内科治疗手段有限,行外科瓣膜置换手术是其有效的治疗方法。然而,根据荟萃分析显示,尽管接受了心脏手术,仍有2.95%(4293/145592)的患者在手术后会出现死亡,其中年老患者的死亡率更高[5]。因此,寻找影响预后的高危因素是具有重要性及紧迫性的。

血清尿酸是嘌呤核苷酸降解的终产物,这已经被证明与几种病理状况下的氧化应激和炎症有关[6-7]。风湿性心脏病伴有心脏扩大、心衰的患者需要使用利尿剂减轻心脏前负荷,此情况在主动脉瓣受累的患者中更为常见[8]。56%患者使用髓袢利尿剂后会出现高尿酸血症,使用醛固酮受体阻滞剂57%患者也同样出现[9]。因此,风湿性心脏病主动脉瓣病变的患者常伴有血尿酸升高的情况。在既往研究,血尿酸已被证明与不良预后独立相关[10-12]。尽管既往已有研究证实血尿酸与心脏手术后急性肾损伤(AKI)之间的关系[13-14],然而,尚无对于血尿酸影响中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换术后患者预后的研究。因此,本研究旨在研究中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换术后患者血尿酸对院内及1年不良事件的预测价值。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象本研究连续性收集2009年3月~2013年7月间在广东省人民医院诊断为风湿性心脏病并接受主动脉瓣瓣膜置换的中老年患者。患者年龄>40岁。所有入选患者在术前行冠状动脉造影术了解冠状动脉情况。风湿性心脏的诊断标准包括:(1)既往风湿热病史;(2)心脏瓣膜结构异常所致的相关症状和心脏杂音;(3)超声心动图检查提示瓣膜瓣叶增厚、粘连、钙化及瓣膜开放或关闭功能不全[15]。

本研究排除标准包括:未接受主动脉瓣置换术、未进行术前血尿酸检测、既往确诊痛风、合并感染、自身免疫性疾病、恶性肿瘤史以及近期接受重大外科手术和创伤的患者。经过严格的纳排标准,最后入选632名患者。所有患者入院后第2天在空腹状态下采集静脉血,通过Beckman Coulter AU5800(Beckman Coulter Inc, California)自动检测血尿酸水平。常规进行心脏彩超检查,通过双平面Simpson方法评估左室射血分数(LVEF)。

1.2 定义和终点事件高尿酸血症定义为男性血清尿酸水平>417 μmol/L(7 mg/dL),女性血清尿酸水平>357 μmol/L(6 mg/dL)。AKI[16]定义为在48 h内血清肌酐增加≥30 μmol/L(0.3 mg/dL)或需要肾脏替代治疗。本研究的主要终点事件是住院期间的全因死亡。所有患者术后均通过电话采访进行了1年的跟踪随访。次要终点包括术后AKI、肾替代治疗及术后1年的全因死亡。

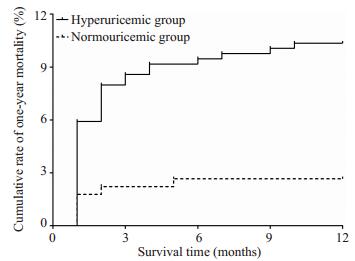

1.3 统计学分析统计分析采用SPSS 13.0。描述性分析采用均数±标准差,M(IQR),%,n。正态连续变量采用两独立样本t检验。非正态变量采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。分类资料采用χ2检验或fisher检验。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。采用单因素Logistic回归法校正住院死亡的混杂因素。P < 0.05的指标进行多变量分析进一步评估。采用Kaplan-Meier曲线分析1年死亡率的累积率,并采用Log-rank检验进行比较。

2 结果 2.1 基线资料比较本研究共纳入632例患者(女性占64.2%,年龄58± 6岁),其中高尿酸血症组381例,血尿酸正常组251例(表 1)。高尿酸血症组尿酸平均值489.2±98.1 μmol/ L,血尿酸正常组尿酸314.5±58.6 μmol/L,P < 0.001。两组比较,高尿酸血症组患者平均年龄较大(58.0±6.0岁vs 57.0±5.8岁,P=0.026)。高尿酸血症组中同时行二尖瓣手术置换率(90.8% vs 85.7%,P= 0.045)、同时行三尖瓣手术干预率(76.9% vs 68.9%,P= 0.026)和血清肌酐(88.1±28.6 μmol/L vs 74.2±18.5 μmol/L,P < 0.001)均高于血尿酸正常组。高尿酸血症组的LVEF比血尿酸正常组低(60.3±10.2% vs 62.5±8.3%,P=0.004)。住院期间患者死亡34例(5.4%),其中高尿酸血症组29例(7.6%),血尿酸正常组5例(2.0%),高尿酸血症组的院内死亡率高于血尿酸正常组(P < 0.002)。此外,高尿酸血症组的术后AKI发生率有增长趋势(66.9% vs 60.2%,P=0.082)。

| 表 1 基线资料的比较 Table 1 Comparison of baseline data of the patients between the two groups |

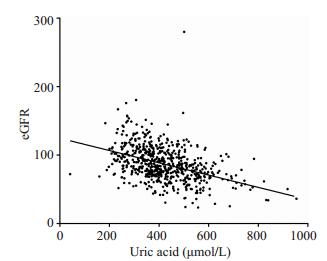

血尿酸与肾小球滤过率(eGFR)呈负相关(r=-0.421,P < 0.001),与C反应蛋白(CRP)呈正相关(r= 0.093,P=0.025)。绘制的散点图显示血尿酸与eGFR呈线性相关(图 1)。

|

图 1 血清尿酸水平与eGFR值相关性分析 Figure 1 Correlation analysis of serum uric acid and eGFR. |

单因素Logistic回归分析显示尿酸水平与院内死亡有关。其他混杂因素包括年龄、糖尿病、纽约心脏协会(NYHA)心功能Ⅲ~Ⅳ级、eGFR < 60 mL/min、1.73 m2、接受冠状动脉旁路移植术(CABG)和术后AKI。采用多重Logistic回归分析,结果显示血尿酸(OR=3.07,95% CI:1.13,8.37,P=0.028),年龄(OR= 1.08,95% CI:1.01,1.15,P=0.026),NYHA心功能Ⅲ~ Ⅳ级(OR=2.47,95% CI:1.15,5.32,P=0.021)和术后AKI(OR=3.34,95% CI:1.13,9.86,P=0.029)与院内死亡独立相关(表 2)。

| 表 2 院内及1年死亡的多因素分析 Table 2 Multivariate analysis of in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates |

对563例(89.1%)患者完成术后1年的随访,其中高尿酸血症组338例,血尿酸正常组225例。在此随访期间,死亡41人(6.4%),其中高尿酸血症组35例,血尿酸正常组6例,高尿酸血症组死亡率高于血尿酸正常组(10.4% vs 2.7%,P=0.001)。多因素Cox比例风险分析显示,校正其他混杂因素(包括年龄、NYHA心功能Ⅲ~Ⅳ级和术后AKI)后,高尿酸血症与1年死亡独立相关(HR=3.14,95% CI:1.30,7.62,P=0.011,表 2)。采用Kaplan-Meier曲线分析显示,高尿酸血症患者的1年死亡累积率较高(Log-rank= 11.73,P=0.001,图 2)。

|

图 2 术后1年死亡的Kaplan-Meier曲线分析 Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of the 1-year postoperative death in the patients. |

大样本研究显示,风湿性瓣膜病患者尽管接受了手术治疗,仍有4.8%的患者在心脏围手术期或短期内死亡[17]。因此,寻找影响此病预后的高危因素是重要且必要的。血清尿酸是嘌呤核苷酸的代谢产物,已被应用于多种疾病中作为预测指标,包括急性肾脏疾病、急性心肌梗死和脑卒中,作为事件的独立预测因子[10-12]。尽管既往已有研究证实血尿酸与心脏手术后AKI之间的关系,但是目前尚不清楚血尿酸升高与中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换后的死亡率是否有关。本研究中,有5.4%的患者出现院内死亡,这与EuroSCORE数据库相似。本研究基线数据显示,60.3%(381/632)患者在术前伴有高尿酸血症,经回归分析校正影响预后的混杂因素后,高尿酸血症是中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换后患者院内及1年死亡的独立预测因子,且本研究结果显示这种关系并不受患者基线eGFR水平的影响(HR=1.34,95% CI:0.64,2.81,P=0.438)。

高尿酸血症与院内死亡率相关的机制尚不清楚。一方面,是尿酸与术后AKI的关系。Lee等[13]揭露了术前尿酸水平与术后AKI的发生有关,其研究结果提示,术前测量血尿酸浓度有助于对冠脉搭桥患者术后发生AKI进行危险分层评估。此外,有研究表明尿酸可能是接受心脏瓣膜和动脉瘤手术患者发生AKI的新型危险因素[14]。另一方面,AKI已被证明是不良事件的预测因子。荟萃分析显示,心脏术后AKI使术后早期死亡率增加了2倍以上[18],且与长期死亡风险增加相关[19]。本研究中,高尿酸血症患者的AKI发生率也有升高趋势。因此,我们推测尿酸的预后价值可能是由它对AKI的影响引起的。但是,这并不是唯一的原因。

在动物研究中,发现尿酸从坏死组织中释放并诱导炎症细胞死亡[20]。此外,尿酸改变由CRP表达介导的人血管细胞的增殖/迁移和一氧化氮释放,据报道其与心脏手术后的不良预后独立相关[21-23]。本研究我们还发现血清尿酸水平与CRP呈正相关。这表明高尿酸血症与死亡率有关可能是由炎症引起的。

本研究显示尿酸水平与eGFR呈负相关,此结果与既往研究结果相似。既往研究显示,慢性肾脏疾病是高血尿酸的独立预测因素,高血尿酸和慢性肾脏疾病与急性心力衰竭患者的不良预后相关[24],且慢性肾脏疾病已经被证明与心功能不全患者的不良预后相关[25-26]。风湿性心脏病患者的心脏瓣膜属永久性损伤,常伴发充血性心力衰竭[27],甚至是急性心力衰竭,这种情况在累及主动脉瓣的风心病患者中更为常见。这些证据可以支持我们的发现,高尿酸血症与中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换后患者的不良预后相关。作为便宜且简单的测量指标,高尿酸血症是中老年风湿性主动脉瓣置换后患者院内死亡的独立预测因子。在随访期间,高尿酸血症患者的1年死亡率显著升高。本研究指出,应该更多地关注需接受手术治疗且合并高尿酸血症的中老年风湿性主动脉瓣患者。我们建议在中老年风湿性主动脉瓣患者接受手术治疗前将血尿酸作为风险评估指标。

| [1] | Kumar RK, Tandon R. Rheumatic fever & rheumatic heart disease: the last 50 years[J]. Indian J Med Res, 2013, 137(4): 643-58. |

| [2] | 饶栩栩, 黄震东. 我国风湿性心脏病的流行现状[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 1998, 26(2): 98-100. |

| [3] | 李霞, 张水旺, 郭文玲. 成年风湿性心脏病患者20年发病演变趋势(摘要) J][J]. 中国循环杂志, 2001, 16(5): 353. |

| [4] | 刘小清. 我国风湿性心脏病近年的流行状况[C]. 2008: 25. http://cpfd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CPFDTOTAL-ZHYX200806001845.htm |

| [5] | Guida P, Mastro F, Scrascia G, et al. Performance of the European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation Ⅱ: a meta-analysis of 22 studies involving 145, 592 cardiac surgery procedures[J]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2014, 148(6): 3049-57. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.039. |

| [6] | Shi Y. Caught red-handed: uric acid is an agent of inflammation[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120(6): 1809-11. DOI: 10.1172/JCI43132. |

| [7] | Leyva F, Anker S, Swan JW, et al. Serum uric acid as an index of impaired oxidative metabolism in chronic heart failure[J]. Eur Heart J, 1997, 18(5): 858-65. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015352. |

| [8] | Marijon E, Mirabel M, Celermajer DS, et al. Rheumatic heart disease[J]. Lancet, 1966, 41(3): 27-30. |

| [9] | Lin CS, Lee WL, Hung YJ, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and its association with antihypertensive treatment in hypertensive patients in Taiwan[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2012, 156(1): 41-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.033. |

| [10] | Guo W, Liu Y, Chen JY, et al. Hyperuricemia is an Independent predictor of Contrast-Induced acute kidney injury and mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention[J]. Angiology, 2015, 66(8): 721-6. DOI: 10.1177/0003319714568516. |

| [11] | Trkulja V, Car S. On-admission serum uric acid predicts outcomes after acute myocardial infarction: systematic review and metaanalysis of prognostic studies[J]. Croat Med J, 2012, 53(2): 162-72. DOI: 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.162. |

| [12] | Chiquete E, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Murillo-Bonilla LM, et al. Serum uric acid and outcome after acute ischemic stroke: PREMIER study[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2013, 35(2): 168-74. DOI: 10.1159/000346603. |

| [13] | Lee EH, Choi JH, Joung KW, et al. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass surgery[J]. J Korean Med Sci, 2015, 30(10): 1509-16. DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.10.1509. |

| [14] | Ejaz AA, Beaver TM, Shimada M, et al. Uric acid: a novel risk factor for acute kidney injury in high-risk cardiac surgery patients[J]. Am J Nephrol, 2009, 30(5): 425-9. DOI: 10.1159/000238824. |

| [15] | Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World heart federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2012, 9(5): 297-309. DOI: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7. |

| [16] | Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury[J]. Crit Care, 2007, 11(2): R31. DOI: 10.1186/cc5713. |

| [17] | Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, et al. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients[J]. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 1999, 15(6): 816-22. DOI: 10.1016/S1010-7940(99)00106-2. |

| [18] | Pickering JW, James MT, Palmer SC. Acute kidney injury and prognosis after cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2015, 65(2): 283-93. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.008. |

| [19] | Corredor C, Thomson R, Al-Subaie N. Long-term consequences of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 2016, 30(1): 69-75. DOI: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.07.013. |

| [20] | Kono H, Chen CJ, Ontiveros F, et al. Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120(6): 1939-49. DOI: 10.1172/JCI40124. |

| [21] | Kang DH, Park SK, Lee IK, et al. Uric acid-induced C-reactive protein expression: Implication on cell proliferation and nitric oxide production of human vascular cells[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2005, 16(12): 3553-62. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2005050572. |

| [22] | Cappabianca G, Paparella D, Visicchio G, et al. Preoperative C-reactive protein predicts mid-term outcome after cardiac surgery[J]. Ann Thorac Surg, 2006, 82(6): 2170-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.039. |

| [23] | Kim DH, Shim JK, Hong SW, et al. Predictive value of C-reactive protein for major postoperative complications following off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: prospective and observational trial[J]. Circ J, 2009, 73(5): 872-7. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-1010. |

| [24] | Okazaki H, Shirakabe A, Kobayashi N, et al. The prognostic impact of uric acid in patients with severely decompensated acute heart failure[J]. J Cardiol, 2016, 68(5): 384-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.04.013. |

| [25] | Shiba N, Shimokawa H. Chronic kidney disease and heart failure--Bidirectional close Link and common therapeutic goal[J]. J Cardiol, 2011, 57(1): 8-17. DOI: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.09.004. |

| [26] | Hamaguchi S, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kinugawa S, et al. Chronic kidney disease as an Independent risk for long-term adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure in Japan. Report from the Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD)[J]. Circ J, 2009, 73(8): 1442-7. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0062. |

| [27] | Remenyi B, Elguindy A, Smith SC, et al. Valvular aspects of rheumatic heart disease[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(125): 1335-46. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37