2. Department of Biostatistics School of Public Health,Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515;

3. Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China,Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, USA

2. 南方医科大学公共卫生学院生物统计学系,广东 广州 510515;

3. 耶鲁大学公共卫生学院生物统计学系, 美国 纽黑文

Retained products of conception (RPOC) are estimated to occur in about 1% of term pregnancies and much more frequently after miscarriage or termination of pregnancy (TOP) worldwide[1-3]. Recent studies reported high incidences of RPOC in Chinese women varying from 2.3% to 21.3% after second trimester TOP[4-6].

For treatment of RPOC, curettage has long been used to stop bleeding, eliminate infection or prevent long-term complications[7], and recent studies showed a high curettage rate ranging from 30.8% to 59% after second trimester TOP[8-11]. In spite of the wide use of curettage for management of RPOC, concerns have been raised over its potential postoperative complications such as pelvic infection[12], uterine perforation[7, 13], cervical laceration[14], intrauterine adhesions (IUAs)[7, 15], infertility[16] and the need a second evacuation of the uterus following surgical intervention of incomplete miscarriage[17].

Several studies have shown that expectant management is convenient, effective, safe and cost-effective for first-trimester incomplete miscarriage as compared to surgical evacuation[12, 18-22] with a reported success rate varying from 25% to 100%[23-26]. But so far, the prognosis and risks of complications associated with curettage and expectant therapy for management of RPOC after second trimester TOP remain to be clarified. In this study, we aimed to investigate the prognosis and complications in women receiving expectant therapy or curettage for RPOC after second trimester TOP.

PATIENTS AND METHODS Patient selectionBetween January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2015, consecutive patients with RPOC following second trimester TOP in Nanfang Hospital were enrolled. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Committee at Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University. The patients were included if they were otherwise healthy, had a single intrauterine pregnancy of 13 weeks or more, regularly returned for routine follow-up and were willing to have telephone interview in the course of follow-up. The patients were excluded for evidence of any past or present chronic disease that may potentially complicate pregnancy or cause serious obstetric complications, such as uncontrolled asthma, liver disease, hemolytic disorders, thromboembolism and hypertension. Patients who missed the immediate ultrasound assessment or failed to show compliance with follow-up in the outpatient clinic were also excluded.

Diagnosis and treatmentThe women undergoing second trimester TOP at our medical center received abdominal ultrasound examination within 48 h after fetus and placental expulsion to assess the uterine cavity. The criteria for diagnosis of RPOC included the presence of clinical symptoms (abnormal vaginal bleeding), ultrasound findings of irregular lining of the uterine wall with echogenic mass or hyperechoic foci and extension of the uterine wall into the cavity[27]. The patients were counseled about possible complications and the need for close observation once they were diagnosed with RPOC. The choice between expectant therapy and curettage for treatment was made at the physician's discretion with full consideration of the ultrasound findings and the patients' preference. All the patients were fully informed of the treatments and gave written informed consent before the treatment. Expectant therapy for RPOC was either initiative (in cases of spontaneous absorption or expulsion of the retained product) or passive (in cases at risk of massive hemorrhage following curettage for possible placenta increta). Immediate curettage was performed in case of a retained placenta or severe blood loss, or when a placental remnant was suspected based on clinical symptoms and ultrasonographic assessment of the uterine cavity. Curettage for removal of the RPOC was performed using a standardized technique by experienced obstetricians. Briefly, the cervix was dilated with Hegar's dilators to 7-8 mm through which a curette was inserted into the uterus, and the lining of the uterus was gently scraped to remove the retained tissue in the uterus.

Data collectionWe searched the digital database of the patients at our department to retrieve the data of the medical records (age, gravidity, parity, and gestational age), description of the abortion (i.e., history of uterine surgery, indications, regimens for TOP and induction-abortion interval), clinical presentations at the time of RPOC diagnosis (i.e., asymptomatic patients and bleeding), outcomes (i.e., duration of vaginal bleeding and recovery time of normal menstruation), and complications related to curettage or expectant therapy. Because the clinical data of β-HCG was incomplete in these patients, we did not compare the level of β-HCG or the duration of negative β-HCG. Complications were defined as the presence of at least one of the symptoms: severe vaginal bleeding requiring intervention, hospitalization for endometritis, abdominal/pelvic pain, polymenorrhea, hypomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.

Follow-upAll the patients were routinely followed up at the outpatient clinic at 1, 2, and 6 weeks after fetus and placental expulsion or sooner if the patients had such complaints as abnormal vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain and smelly lochia that require medical attention. Ultrasound examination was performed if the patients had irregular vaginal bleeding or complained of persistent or abdominal pain. During the follow-up, irregular vaginal bleeding or infections were managed with a second curettage, hysteroscopy, or antibiotics. The menstrual cycle, complications, the need for a second intervention, and the outcomes of fertility and pregnancy within 2 years following the treatments were recorded during follow-up.

Statistical analysisFor continuous variables, the data are presented as Mean±SD or medians with the interquartile range (IQR). The differences between the two groups were tested using independent Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney U Test as appropriate. The categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test between the two groups. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the risk factors for the complications in bivariate and multivariate analyses, and the results are presented as the odds ratio (OR) with the 95% confidence interval (CI). All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

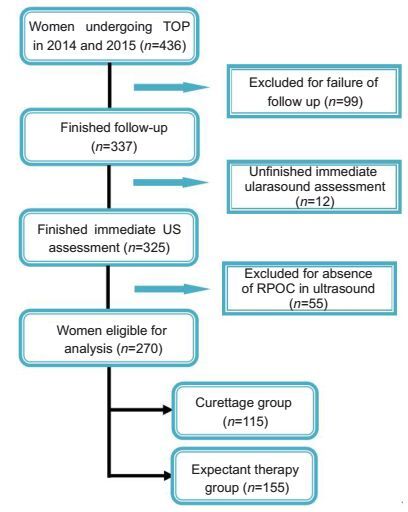

RESULTS Patient characteristicsA total of 436 patients were initially recruited for screening. Fig. 1 presents the flow diagram illustrating the screening procedure. Of the 436 patients, 99 were excluded due to follow-up loss or non-compliance; 12 were excluded due to failure in immediate ultrasound assessment before discharge; and 55 were excluded due to absence of abnormal ultrasound findings in the uterine cavity. Finally, a total of 270 patients were included in the study, among whom 115 patients received curettage and 155 received expectant therapy for RPOC. None of the patients had such complications as placenta accreta or placenta increta.

|

Figure 1 Flow chart illustrating the procedure of patient selection. |

The basic characteristics of the two groups of patients are summarized in Tab. 1. The patients in curettage and expectant therapy groups were comparable for age, gravidity, parity, previous uterine surgery, type of indications and regimens for TOP. The median (IQR) gestational age was significantly lower (P= 0.007) and the induction-abortion interval was significantly longer (P < 0.001) in curettage group than in expectant therapy group.

| Table 1 Basic characteristics of the two groups of patients |

As shown in Tab. 2, the duration of vaginal bleeding was significantly longer in expectant therapy group than in curettage group (P=0.005). No significant difference was found in the recovery time of menstruation between the two groups (P=0.287). The percentage of patients with of vaginal bleeding for over 42 days was significantly higher in curettage group than in expectant therapy group (P=0.040). No significant difference was found between the two groups in the percentage of patients with recovery time of menstruation beyond 60 days (P= 0.783).

| Table 2 Outcomes of the treatments for RPOC in the two groups |

Complications after treatment occurred in 2 (1.3%) patients in expectant therapy group and in 14 (12.2%) patients in curettage group (P=0.002). The details of the complications in both groups are listed in Tab. 3. The results of bivariate and multivariate analyses of the risk factors for the complication are shown in Tab. 4. In bivariate analyses, the rate of complication was significantly higher in curettage group than in expectant therapy group (OR=10.60, 95% CI: 2.36-47.66, P=0.002). After adjustment for the patients' age, gravidity, parity, previous uterine surgery, gestational age, types of indications, regimens for TOP and induction-abortion interval, the rate of complication was still significantly higher in curettage group (OR=18.26, 95% CI: 3.57-93.42, P < 0.001).

| Table 3 Complications after treatment for RPOC in the two groups (n) |

| Table 4 Bivariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for the complications |

Overall, a cumulative conception rate of 12.6% (34/270) was recorded in short-term follow-up, including 19 in curettage group and 15 in expectant therapy group. Follow-up of the pregnancy outcomes showed that in curettage group, one woman experienced spontaneous miscarriage in the first trimester, one had missed abortion at 11+3 weeks, one had preterm delivery at the gestational age of 29 weeks, and 16 patients had term deliveries; in expectant therapy group, one woman had spontaneous miscarriage in the first trimester, one underwent another first trimester TOP due to unintended pregnancy, and 13 had uneventful ongoing pregnancies.

DISCUSSIONWe found in this study that patients receiving expectant therapy or curettage for RPOC after TOP had comparable outcomes, and curettage was associated with a significantly higher rate of complications compared with expectant therapy.

The patients receiving expectant therapy for RPOC had a longer duration of vaginal bleeding than those undergoing curettage, but the menstruation recovery time was similar between the two groups, and these results were consistent with the findings in previous studies[12, 18, 22, 28-31]. In spite of the longer duration, vaginal bleeding was mostly mild in patients with expectant therapy. We found a significantly higher incidence of vaginal bleeding for over 42 days in patients receiving curettage than in those with expectant therapy and comparable incidences of menstruation recovery time beyond 60 days between the two groups, suggesting that curettage increases the risk of prolonged vaginal bleeding time, which may decrease hemoglobin level and increase the risk of infections. The induction-abortion interval was also longer in curettage group, possibly because, as we hypothesized, the women with longer induction-abortion intervals were more likely to develop RPOC, and in such cases, obstetricians preferred curettage over expectant therapy to avoid potential massive postpartum hemorrhage caused by RPOC.

In this cohort we found a high risk of postoperative complication in patients receiving curettage for RPOC, as was consistent with previous studies[32, 33]. But some studies also reported similar complication rate between patients having expectant management and surgical treatment[12, 18, 31]. We presume that this discrepancy may arise from the differences in the characteristics of the patient populations that had been studied: the gestational age, the type of pregnancy loss, and the sample size all contribute to the conclusion.

Due to the short term of follow-up, we were not able to confirm the overall conception rate and reproductive outcomes in this cohort. The data we collected so far showed no significant difference in the conception rate or the reproductive outcomes between the curettage group and expectant therapy group.

Considering the high rate of complications associated with curettage for RPOC and the similar prognoses and reproductive outcomes between expectant management and curettage, we believe it is time to question the high rate of curettage that causes inevitable trauma to the uterus. The International Conference on Second Trimester Abortion conducted by ICMA and FIGO in March, 2007, in London recommended that the use of curettage to complete second trimester abortion should be avoided, and where necessary, be replaced by suction[34]. Our results support this recommendation and demonstrate that expectant therapy, as a practical alternative to curettage, is both safe and effective for management of RPOC following a second trimester TOP.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size, clearly defined case groups, and the use of bivariate and multivariate analyses that were robust to control for the measured potential confounders. Nevertheless, this study has inherent limitations for its retrospective nature. In addition, we collected some data from patients through telephone interview, which could be liable to recall bias. Although we had controlled for the potential confounders in the multivariate analyses, we do not exclude the possibility of other unmeasured confounding variables (e.g. socioeconomic status and body mass index); and we could not control for other clinical factors such as serum β-HCG level, the period of β-HCG negativity, consistency in routine care provided by different medical teams and the provider-level differences regarding curettage.

ConclusionTreatment of RPOC after TOP with expectant therapy or curettage has comparable prognosis in terms of the duration of vaginal bleeding and the recovery time of menstruation, while curettage is associated with a significantly higher rate of complication. Expectant therapy is both safe and effective for the management of RPOC following a second trimester TOP, and can serve as a practical alternative to curettage.

| [1] | Van den Bosch T, Daemen A, Van Schoubroeck D, et al. Occurrence and outcome of residual trophoblastic tissue:a prospective study[J]. J Ultrasound Med, 2008, 27(3): 357-61. DOI: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.3.357. |

| [2] | Hoveyda F, MacKenzie IZ. Secondary postpartum haemorrhage:incidence, morbidity and current management[J]. BJOG, 2001, 108(9): 927-30. |

| [3] | Zalel Y, Cohen SB, Oren M, et al. Sonohysterography for the diagnosis of residual trophoblastic tissue[J]. J Ultrasound Med, 2001, 20(8): 877-81. DOI: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.8.877. |

| [4] | Sun LM. The observation on efficacy of second trimester termination of pregnancy by mifepristone combined with misoprostol versus intra-amniotic Rivanol injection[J]. J Pract Gynecol Endocrinol, 2015, 2(9): 190-2. |

| [5] | Sun XF, Kong GQ. The observation on efficacy of termination of 14-20 weeks pregnancy by mifepristone combined with misoprostol versus intra-amniotic Rivanol injection[J]. Chin J Healthy Birth Child Care, 2014, 20(8): 557-8. |

| [6] | Sun YR. Clinical observation on the second trimester termination of pregnancy by mifepristone combined with misoprostol and Foly cather[J]. China Medical Herald, 2011, 8(1): 153-4. |

| [7] | Hooker AB, Aydin H, Br lmann HAM, et al. Long-term complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception:a systematic review[J]. Fertil Steril, 2016, 105(1): 156-64. DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.021. |

| [8] | Rasmussen AL, Frostholm GT, Lauszus FF. Curettage after medical induced abortions in second trimester[J]. Sex Reprod Healthc, 2014, 5(3): 156-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.06.002. |

| [9] | Mentula M, Heikinheimo O. Risk factors of surgical evacuation following second-trimester medical termination of pregnancy[J]. Contraception, 2012, 86(2): 141-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.11.070. |

| [10] | Van der Knoop BJ, Vandenberghe G, Bolte AC, et al. Placental retention in late first and second trimester pregnancy termination using misoprostol:a retrospective analysis[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2012, 25(8): 1287-91. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2011.629257. |

| [11] | Mei Q, Li X, Liu H, et al. Effectiveness of mifepristone in combination with ethacridine lactate for second trimester pregnancy termination[J]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014, 178(7): 12-5. |

| [12] | Al-Ma'Ani W, Solomayer EF, Hammadeh M. Expectant versus surgical management of first-trimester miscarriage:a randomised controlled study[J]. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2014, 289(5): 1011-5. DOI: 10.1007/s00404-013-3088-1. |

| [13] | National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Chinese health statistical almanac of health and family planning[M]. Beijing: Pecking Union Medical College Press, 2014: 226-7. |

| [14] | Peterson WF, Berry FN, Grace MR, et al. Second-trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation:an analysis of 11, 747 cases[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 1983, 62(2): 185-90. |

| [15] | Hooker AB, Muller LT, Paternotte E, et al. Immediate and long-term complications of delayed surgical management in the postpartum period:a retrospective analysis[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2014, 28(16): 1884-9. |

| [16] | Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage:prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome[J]. Hum Reprod Update, 2014, 20(2): 262-78. DOI: 10.1093/humupd/dmt045. |

| [17] | Verkuyl DA, Crowther CA. Suction v.conventional curettage in incomplete abortion:a randomised controlled trial[J]. S Afr Med J, 1993, 83(1): 13-5. |

| [18] | Dangalla DP, Goonewardene IM. Surgical treatment versus expectant care in the management of incomplete miscarriage:a randomised controlled trial[J]. Ceylon Med J, 2012, 57(4): 140-5. |

| [19] | Whitley KA, Trinchere K, Prutsman W, et al. Midtrimester dilation and evacuation versus prostaglandin induction:a comparison of composite outcomes[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2011, 205(4): 381-6. |

| [20] | Grossman D, Constant D, Lince N, et al. Surgical and medical second trimester abortion in South Africa:a cross-sectional study[J]. Bmc Health Serv Res, 2011, 11(1): 1-9. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-1. |

| [21] | Lohr PA, Hayes JL, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Surgical versus medical methods for second trimester induced abortion[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008(1): CD6714. |

| [22] | Nanda K, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012(3): CD3518. |

| [23] | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green-top Guideline No. 25: The management of early pregnancy loss. London, October 2006. |

| [24] | Sajan R, Pulikkathodi M, Vahab A, et al. Expectant versus surgical management of early pregnancy miscarriages-a prospective study[J]. J Clin Diagn Res, 2015, 9(10): C6-9. |

| [25] | Luise C, Jermy K, May C, et al. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage:observational study[J]. BMJ, 2002, 324(7342): 873-5. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.873. |

| [26] | de Vries JI, van RM, van HC. Predictive value of sonographic examination to visualize retained placenta directly after birth at 16 to 28 weeks[J]. J Ultrasound Med, 2000, 19(1): 13-4. |

| [27] | Wolman I, Altman E, Faith G, et al. Combined clinical and ultrasonographic work-up for the diagnosis of retained products of conception[J]. Fertil Steril, 2009, 92(3): 1162-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.087. |

| [28] | Wickramasinghe WUS. Surgical treatment versus expectant care in the management of incomplete miscarriage. Thesis for MD Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2010. Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. 2010. |

| [29] | Trinder J, Brocklehurst P, Porter R, et al. Management of miscarriage:expectant, medical, or surgical? Results of randomised controlled trial(miscarriage treatment(MIST)trial)[J]. BMJ, 2006, 332(7552): 1235-40. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.38828.593125.55. |

| [30] | Shelley JM, Healy D, Grover S. A randomised trial of surgical, medical and expectant management of first trimester spontaneous miscarriage[J]. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 2005, 45(2): 122-7. DOI: 10.1111/ajo.2005.45.issue-2. |

| [31] | Waard WD, Vos J, Bonsel GJ, et al. Management of miscarriage:a randomized controlled trial of expectant management versus surgical evacuation[J]. Hum Reprod, 2002, 17(9): 2445-50. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/17.9.2445. |

| [32] | Pather S, Ford M, Reid R, et al. Postpartum curettage:an audit of 200 cases[J]. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol, 2005, 45(5): 368-71. DOI: 10.1111/ajo.2005.45.issue-5. |

| [33] | Chung TK, Lee DT, Cheung LP, et al. Spontaneous abortion:a randomized, controlled trial comparing surgical evacuation with conservative management using misoprostol[J]. Fertil Steril, 1999, 71(6): 1054-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00128-4. |

| [34] | Zaidi S, Begum F, Tank J, et al. Achievements of the FIGO Initiative for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortion and its Consequences in South-Southeast Asia[J]. Int J Gynecol Obstet, 2014, 126 suppl 1(3): S20-3. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37