2. 清华大学生物医学影像研究中心,北京 100084;

3. 解放军总医院第一附属医院神经内科,北京 100048;

4. 解放军总医院第一附属医院放射科,北京 100048;

5. 首都医科大学北京脑重大疾病研究院,北京 100069

2. Center for Biomedical Imaging Research, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China;

3. Department of Neurology, First Affiliated Hospital of General Hospital of PLA, Beijing 100048, China;

4. Department of Radiology, First Affiliated Hospital of General Hospital of PLA, Beijing 100048, China;

5. Beijing Institute of Brain Disorders, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100069, China

动脉粥样硬化(AS)斑块破裂引发的急性血栓栓塞是导致心脑血管事件的主要原因之一。作为AS易损斑块组织学特点之一,斑块内出血(IPH)可以通过增加斑块内脂质体积、促进炎性反应、改变斑块机械力环境加速了斑块的进展[1-2],进而导致斑块纤维帽破裂,最终引发血栓栓塞事件。IPH被认为是再发性脑缺血症状[3]的预测因素之一,并与颅内卒中具有明显的相关性[4],如区域性的脑梗死和分水岭区脑梗死[5-6]。研究发现,缺血性脑血管病病灶同侧的颈动脉斑块存在IPH更为常见[7],进一步提示IPH促进脑缺血性卒中事件的作用。

尽管颈动脉斑块IPH与脑缺血性卒中事件的相关性以及与斑块易损性之间关系已得到证实,然而,对于单侧及双侧颈动脉AS斑块发生IPH的患者,其斑块的危险程度是否存在差异却未有研究报道。因此,本研究旨在探讨含IPH的单、双侧颈动脉AS斑块易损性差异,为IPH的发生机制提供分析依据,并且为颈动脉AS斑块患者脑缺血性卒中事件发生风险提供预测依据。

1 资料和方法 1.1 研究对象回顾性分析2009年12月~2012年12月间来我院行颈动脉高分辨磁共振检查的患者。纳入标准:单侧或双侧颈动脉AS斑块发生IPH;排除标准:单侧或双侧颈动脉闭塞。与动脉粥样硬化相关的临床资料从患者病历中查找获得。其中入选颈动脉斑块出血患者44例,男性36例(82%),平均年龄71.4±9.6岁,体质量指数(BMI)24.6±3.5 kg/m2,高血脂16例(36.4%),高血压27例(61.4%),糖尿病8例(18.2%),冠心病14例(31.8%),吸烟7例(15.9%),详细信息在表 1中列出。本研究方案已通过机构伦理委员会审查,所有患者均已签署知情同意书。

| 表 1 患者临床特点 Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled (n=44) |

所有患者均行双侧颈动脉磁共振多对比度黑血管壁成像检查。磁共振成像采用3.0 T磁共振(SignaHDx, General Electric Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA)及4通道颈部相控阵线圈(Department of Radiology, University of Washington, USA)。颈动脉管壁成像方案使用了T1加权(T1 weighted imaging T1WI)、T2加权(T2 weighted imaging T2WI)、3D时间飞跃(3 dimensional time of flight 3D-TOF)序列。扫描参数分别为:3D-TOF:3D梯度回波序列,TR/TE 29/2.1 ms,翻转角20°,层数26,层厚2 mm,视野140 mm×140 mm,矩阵256×256,回波链长度1;T1WI:四翻转恢复快速自旋回波序列,TR/TE 800/ 7.3 ms,翻转角90°,层数12,层厚2 mm,纵向覆盖范围24 mm;视野140 mm×140 mm,矩阵256×256,回波链长度12;T2WI:快速自旋回波序列,TR/TE 3000/60 ms,翻转角90°,层数16,层厚2 mm,视野140 mm×140 mm,矩阵256×256,回波链长度10。

1.2.2 图像分析两名有两年以上动脉管壁影像判读经验的放射诊断医师采取观点一致性原则对斑块图像进行判读。首先对图像质量进行评估,图像质量按信噪比程度分为4个等级:1级为差,4级为优。1级:图像质量差,管腔和管壁境界显示不清,有明显运动和血流伪影,斑块成分无法分辨;2级:图像质量不佳,大部分管腔和管壁境界边界尚清楚,可有运动和血流伪影,斑块成分无法分辨;3级:图像质量好,大部分管腔和管壁境界边界清楚,可有少许运动和血流伪影,斑块成分清晰可辨;4级:图像质量优,管腔和管壁境界边界清楚,无运动和血流伪影,斑块成分清晰可辨,本研究中评分≤2级的图像被剔除。在管壁横轴位图像上应用CASCADE软件(Vascular Imaging Lab, University of Washington)半自动勾画动脉管腔、管壁及斑块成分如钙化、IPH的边界,并对管壁斑块的最大管壁厚度和管腔狭窄程度进行定量测量。定量测量各斑块成分的体积。应用图像工作站(AW4.5 GE Healthcare)对3D-TOF图像进行最小信号强度投影,采用NASCET标准测量管腔狭窄程度。IPH在T1WI和3D-TOF序列上表现为高信号。钙化在各个序列上均显示为低信号。纤维帽破裂表现为在3D-TOF序列上斑块表面“黑带”部分消失,由高信号替代,包括裂隙状纤维帽破裂及溃疡[8],裂隙状的纤维帽破裂核磁表现为,3D-TOF序列和T1WI上可见斑块内线条状高信号(斑块内出血)一直延伸至管腔,其与管腔血流信号之间无等信号纤维帽覆盖[9]。溃疡表现为3D-TOF序列、T1WI和T2WI上斑块表面破溃,形成不规则局限性缺损,缺损区域在3D-TOF序列图像上可见与管腔相通的不均匀血流信号,缺损区域在T1WI和T2WI上血流信号被抑制[10]。

1.2.3 统计学方法选择患者双侧颈动脉中斑块易损性较严重的一侧进入研究(单侧IPH组为发生IPH侧颈动脉,双侧IPH组为斑块负荷较大侧颈动脉)。所有连续性变量使用均数±标准差描述,分类变量使用百分率进行描述。对单、双侧发生IPH两组间的相关变量进行统计检验,服从正态分布及方差齐使用两组独立样本t检验,不服从的变量则使用Wilcoxon秩和检验。对两组间的纤维帽破裂和溃疡发生率进行卡方检验。另外使用Logistic回归分析纤维帽破裂和单双侧IPH的相关性。双侧P < 0.05表示有统计学意义。采用SPSS 22.0统计软件完成上述统计学分析。

2 结果 2.1 颈动脉斑块成分及负荷的MR特征在入选的44例颈动脉IPH患者中,单侧IPH患者30例(68%),双侧IPH患者14例(32%)。所有入选的44根颈动脉中,发生纤维帽破裂共35例(80%),其中包括溃疡11例(25%)。单侧IPH(IPH单)组纤维帽破裂21(70%)例,双侧IPH(IPH双)组纤维帽破裂14例(100%)例。IPH单组溃疡4(13%)例,IPH双组溃疡7例(50%)。斑块的最大管壁厚度为5.5±1.6 mm,狭窄程度为(42± 21)%。斑块特点信息在表 2中显示。

| 表 2 斑块特点 Table 2 Plaque characteristics in these patients (n=44) |

IPH双组发生溃疡的概率显著高于IPH单组(50% vs 13%,P=0.025)。Logistic回归分析发现,双侧IPH与溃疡的发生明显相关(OR=6.5,95% CI 1.5~28.7,P= 0.014),模型1校正了性别,两者之间的相关性仍可见显著统计学意义(OR=5.7,95%CI 1.1~29.2,P=0.036)。然而,模型2中额外校正年龄(P=0.131)或最大斑块厚度(P=0.139)后,双侧IPH与溃疡的相关性未见明显统计学差异。IPH双组纤维帽破裂的概率高于IPH单组(100% vs 70%,P=0.058),尽管未见显著统计学差异。

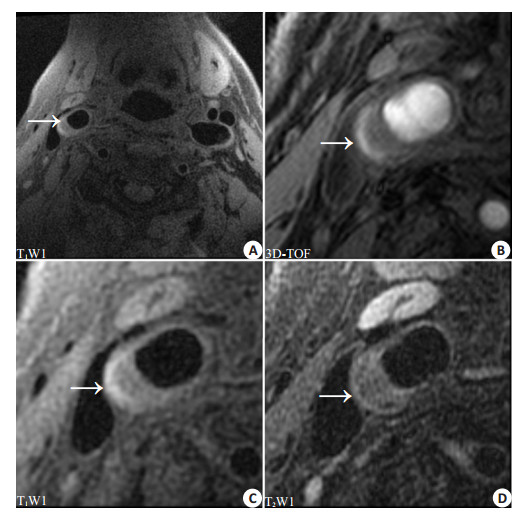

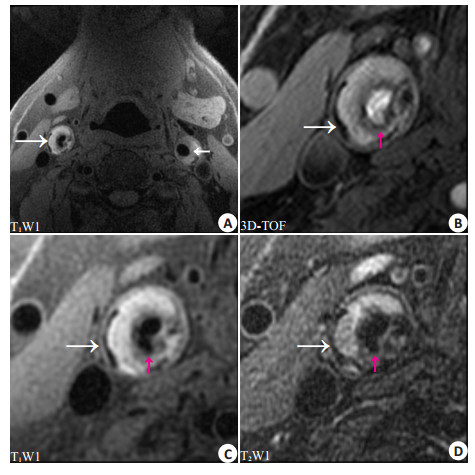

研究发现IPH双组患者年龄小于IPH单组(66.6±9.4 vs 73.7±9.0,P=0.027)。对于斑块的负荷而言,IPH双组斑块最大厚度高于IPH单组(6.3±1.9 vs 5.0±1.3 mm,P= 0.035),但两组间狭窄程度未见统计学差异(0.39±0.23 vs 0.48±0.18,P=0.21)。图 1、图 2即显示了两名患者中,相对较年轻的患者发生了双侧IPH,并在斑块负荷较严重侧发生斑块溃疡。

|

图 1 单侧IPH患者颈动脉多对比MR成像 Figure 1 Multi-contrast MRI of an 80-year-old male patient with unilateral IPH. A: IPH (arrow) with hyperintensity on T1WI in the right carotid atherosclerotic plaque; B, C and D: Multi-contrast MR images of the right carotid plaque showing intact plaque surface. |

|

图 2 双侧IPH患者颈动脉多对比MR成像 Figure 2 Multi-contrast MRI of a 60-year-old male patient with bilateral IPHs. A: IPHs (white arrows) with hyperintensity on T1WI in the bilateral carotid atherosclerotic plaques; B, C and D: Multi-contrast MR images of the right carotid plaque showing an ulcer on the plaque surface (red arrows). |

本研究发现双侧发生IPH的患者其较严重侧斑块发生纤维帽破裂、溃疡的可能性更大。双侧IPH患者年龄明显小于单侧IPH患者,但其较严重侧斑块的最大斑块厚度大于单侧IPH组。对单、双侧IPH和斑块的发生溃疡的相关性分析发现,双侧IPH与较严重侧斑块溃疡的发生具有明显的相关性。

本研究结果显示IPH双组斑块最大厚度大于IPH单组。前期研究发现IPH可以促进斑块体积的增长[11],此作用可能是因为红细胞内富含游离胆固醇,并且红细胞可以促进巨噬细胞活化[12]。巨噬细胞的嗜红细胞作用能够增强对低密度脂蛋白(LDL)的氧化作用,导致LDL转化,促进脂质沉积,进入巨噬细胞[13],进而促进了斑块的增长。另外,研究发现IPH双组纤维帽的稳定性明显低于IPH单组。国外研究证明IPH与纤维帽破裂及溃疡的发生有明显的关系[14]。其原因主要是IPH导致斑块炎症反应活跃[15]、生物力学特点发生改变[2, 16],因此促进了纤维帽发生破裂。IPH可以促进斑块内巨噬细胞活化,而活化的巨噬细胞可以释放大量的蛋白酶和酶激活剂[17],这些蛋白酶作用于纤维帽,使纤维帽稳定性降低,进而发生破裂。本实验结果提示单侧IPH的患者与双侧IPH患者斑块内炎症反应强度可能不尽相同。因此虽然同为存在IPH的斑块,但两组间纤维帽破裂、溃疡的发生率却不同。最近的实验提示药物的使用,如他汀类药物,可以明显的降低斑块内的炎性反应[18]。

逻辑回归分析对单、双侧IPH与溃疡的发生做了相关性分析,结果发现,双侧IPH与溃疡发生具有明显的相关性。本研究在模型中校正年龄或斑块最大厚度后,上述两者的相关性消失。研究结果提示斑块发生溃疡可能和IPH促进斑块体积的增大有关。斑块体积在发生IPH后明显增加,原因可能是红细胞包膜中富含磷脂及游离胆固醇,游离胆固醇在斑块内不能降解,磷脂也聚集在斑块内,促进了斑块内脂质核体积的增加[19]。斑块坏死脂质核体积的增加提高了纤维帽破裂的风险[20]。除此之外,斑块纤维帽的破裂可能还与患者年龄增长有关,由于随着年龄的增加,血管平滑肌细胞增值性能降低,炎症反应活跃,血管的顺应性降低,斑块更容易破裂[21]。

本研究结果显示双侧IPH组患者,其年龄较小,而斑块负荷更大,其原因可能是,促进斑块发生IPH的因素在单、双侧患者间分布情况存在差异。目前导致斑块内新生微血管发生渗漏或破裂继而发生IPH的原因尚未清楚。现阶段认为可能与血压值、高血压类型、机体内生物分子的活跃程度及药物使用情况[22]有关。研究发现,与收缩压、舒张压相比,脉压差和斑块IPH的发生关系更加密切,脉压差越大,斑块发生IPH的可能性越大;不同类型的高血压对斑块发生IPH的影响也不相同[23]。另外类胰蛋白酶及基质金属蛋白酶在机体内可以促进斑块IPH的发生[24-25]。这些因素均可能促进IPH的发生。

本研究首次分析了单、双侧颈动脉AS斑块出血两组患者间的斑块负荷、成分、表面状态及年龄间的差别,对单侧和双侧IPH患者其较严重侧的AS斑块危险程度进行对比。研究发现相较于单侧IPH的患者,双侧IPH组其较严重侧的斑块易损性更高,提示双侧IPH的患者其AS斑块的危险性明显高于单侧IPH患者。因此,对斑块危险性进行分析时,双侧IPH的出现可能提示了患者未来斑块不稳定性更高,应该特别受到重视。另外,本研究还对IPH的发生机制,以及IPH促进斑块进展,增加斑块不稳定性等问题进行了探讨。研究发现,斑块发生IPH的原因,以及之后斑块进展可能与多种因素有关,如药物使用情况、血压、血脂等。

本研究存在一定的局限性:首先,样本数量较少,亟待大样本的试验来进行进一步的验证。其次,扫描范围较小,部分斑块不能完整覆盖,对斑块成分分析具有一定限制。最近的3D血管管壁成像技术可以提供更大的扫描范围[26],可以作为后期研究的一个重要的检查手段。再次,本研究为回顾性研究,因此需要后续的前瞻性研究进行进一步探索。

| [1] | Kodama T, Narula N, Agozzino M, et al. Pathology of plaque haemorrhage and neovascularization of coronary artery[J]. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown), 2012, 13 (10): 620-7. DOI: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328356a5f2. |

| [2] | Teng Z, Sadat U, Brown AJ, et al. Plaque hemorrhage in carotid artery disease: pathogenesis, clinical and biomechanical considerations[J]. J Biomech, 2014, 47 (4): 847-58. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.01.013. |

| [3] | Altaf N, Macsweeney ST, Gladman J, et al. Carotid intraplaque hemorrhage predicts recurrent symptoms in patients with high-grade carotid stenosis[J]. Stroke, 2007, 38 (5): 1633-5. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.473066. |

| [4] | Yamada K, Kawasaki M, Yoshimura S, et al. High-Intensity signal in carotid plaque on routine 3D-TOF-MRA is a risk factor of ischemic stroke[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis, 2016, 41 (1/2): 13-8. |

| [5] | Isabel C, Lecler A, Turc G, et al. Relationship between watershed infarcts and recent intra plaque haemorrhage in carotid atherosclerotic plaque[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9 (10): e108712. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108712. |

| [6] | Park JS, Kwak HS, Lee JM, et al. Association of carotid intraplaque hemorrhage and territorial acute infarction in patients with acute neurological symptoms using carotid magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with gradient-echo[J]. J Korean Neurosurg Soc, 2015, 57 (2): 94-9. DOI: 10.3340/jkns.2015.57.2.94. |

| [7] | Kerwin WS. Carotid artery disease and stroke: assessing risk with vessel wall MRI[J]. ISRN Cardiol, 2012 (8): 180710. |

| [8] | Cai JM, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, et al. Classification of human carotid atherosclerotic lesions with in vivo multicontrast magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Circulation, 2002, 106 (11): 1368-73. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000028591.44554.F9. |

| [9] | Kampschulte A, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, et al. Differentiation of intraplaque versus juxtaluminal hemorrhage/thrombus in advanced human carotid atherosclerotic lesions by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Circulation, 2004, 110 (20): 3239-44. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147287.23741.9A. |

| [10] | Yu W, Underhill HR, Ferguson MS, et al. The added value of longitudinal black-blood cardiovascular magnetic resonance angiography in the cross sectional identification of carotid atherosclerotic ulceration[Z], 2009: 31. |

| [11] | Sun J, Underhill HR, Hippe DS, et al. Sustained acceleration in carotid atherosclerotic plaque progression with intraplaque hemorrhage: a long-term time course study[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2012, 5 (8): 798-804. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.03.014. |

| [12] | Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Burke AP, et al. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 349 (24): 2316-25. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa035655. |

| [13] | Yuan XM, Anders WL, Olsson AG, et al. Iron in human atheroma and LDL oxidation by macrophages following erythrophagocytosis[J]. Atherosclerosis, 1996, 124 (1): 61-73. DOI: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05817-0. |

| [14] | Xu DX, Hippe DS, Underhill HR, et al. Prediction of High-Risk plaque development and plaque progression with the carotid atherosclerosis score[J]. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 2014, 7 (4): 366-73. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.09.022. |

| [15] | de Vries MR, Quax PH. Plaque angiogenesis and its relation to inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque destabilization[J]. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2016, 27 (5): 499-506. DOI: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000339. |

| [16] | Sadat U, Teng Z, Young VE, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging-based finite element analysis for the biomechanical stress analysis of hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic carotid plaques[J]. Circ J, 2011, 75 (4): 884-9. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0719. |

| [17] | Welgus HG, Campbell EJ, Cury JD, et al. Neutral metalloproteinases produced by human mononuclear phagocytes. Enzyme profile, regulation, and expression during cellular development[J]. J Clin Invest, 1990, 86 (5): 1496-502. DOI: 10.1172/JCI114867. |

| [18] | Verhoeven B, Moll FL, Koekkoek JA, et al. Statin treatment is not associated with consistent alterations in inflammatory status of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: a retrospective study in 378 patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy[J]. Stroke, 2006, 37 (8): 2054-60. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.0000231685.82795.e5. |

| [19] | Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, et al. Presence of intraplaque hemorrhage stimulates progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study[J]. Circulation, 2005, 111 (21): 2768-75. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504167. |

| [20] | Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL, et al. Predictors of surface disruption with Mr imaging in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2010, 31 (3): 487-93. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A1842. |

| [21] | Monk BA, George SJ. The effect of ageing on vascular smooth muscle cell Behaviour--A Mini-Review[J]. Gerontology, 2015, 61 (5): 416-26. |

| [22] | Liem MI, Schreuder FH, van Dijk AC, et al. Use of antiplatelet agents is associated with intraplaque hemorrhage on carotid magnetic resonance imaging: the plaque at risk study[J]. Stroke, 2015, 46 (12): 3411-5. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008906. |

| [23] | Selwaness M, van den Bouwhuijsen QJ, Verwoert GC, et al. Blood pressure parameters and carotid intraplaque hemorrhage as measured by magnetic resonance imaging: The Rotterdam Study[J]. Hypertension, 2013, 61 (1): 76-81. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198267. |

| [24] | de Nooijer R, Verkleij CJ, von der Thüsen JH, et al. Lesional overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 promotes intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced lesions but not at earlier stages of atherogenesis[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006, 26 (2): 340-6. |

| [25] | Zhi XL, Xu C, Zhang H, et al. Tryptase promotes atherosclerotic plaque haemorrhage in ApoE-/-mice[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8 (4): e60960. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060960. |

| [26] | Wang J, Börnert P, Zhao H, et al. Simultaneous noncontrast angiography and intraplaque hemorrhage (SNAP) imaging for carotid atherosclerotic disease evaluation[J]. Magn Reson Med, 2013, 69 (2): 337-45. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.24254. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37