2. 基础医学院病原生物学教研室;

3. 附属医院临床技能中心, 江西 九江 332000;

4. 江西省南昌大学附属九江医院内分泌科, 江西 九江 332000

2. Department of Pathogenic Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Jiujiang University, Jiujiang 332000, China;

3. Clinical Skills Center, Affiliated Hospital of Jiujiang University, Jiujiang 332000, China;

4. Department of Endocrinology, Jiujiang Hospital Affiliated to Nanchang University, Jiujiang 332000, China

人骨髓间充质干细胞(human mesenchymal stem cells,hMSCs)是一种易于扩增、具有多种分化潜能的细胞[1],在不同诱导条件下,能够向成骨细胞[2]、成软骨细胞[3]和脂肪细胞[4]分化。有研究表明hMSCs 能定向分化为成骨细胞和脂肪细胞,如果成人骨骼中的这两种细胞分化比例失衡(成骨细胞减少、脂肪细胞增多),将导致骨量下降,是骨质疏松发生发展的关键因素[5-6],而有关hMSCs成脂分化方面的研究较少,因此,hMSCs成脂分化调控机制是一个值得关注的研究方向。

miRNAs可以和靶基因mRNA通过碱基配对方式结合来引导沉默复合体降解mRNA或阻碍其翻译[7]。近年来,基因芯片和高通量测序技术得到了广泛运用,已经证实了miRNA与人类许多重要疾病(如肿瘤、免疫性疾病、心血管疾病)的发生、发展密切相关[8-10]。目前,有关hMSCs成脂分化的miRNA研究甚少,筛选出更多具有潜在研究价值的miRNA显得尤为重要。

本研究旨在应用miRNA 芯片和转录组测序(mRNA-seq)技术,分析hMSCs成脂分化中miRNA和mRNA的表达水平,并将miRNA与mRNA的表达趋势进行关联分析,聚焦具有研究价值的miRNA与mRNA相互调控关系。同时,采用多个数据库进行靶基因的预测,取其交集部分作。以期筛选出具有潜在价值的miRNA及其靶基因,为人类成骨细胞与脂肪细胞分化平衡调控机制深入研究提供有力的实验依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料人骨髓间充质干细胞(产品货号:7500)和DMEM培养液(产品货号:7501)购美国Sciencell公司(上海兴泊生物科技公司代理)、胰蛋白酶和油红O(美国Gibco公司);分化诱导剂(美国Sigma公司):胰岛素、地塞米松、1-甲基-3-异丁基黄嘌呤(1-methyl-3-isobuthylxanthine,IBMX)、吲哚美新。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 人骨髓间充质干细胞培养取出液氮保存的hMSCs细胞,复苏接种于康宁Corning一次性细胞培养瓶(25 cm2)中,加入新鲜DMEM培养液5 mL,放入5%CO2培养箱内37 ℃培养,每间隔2 d换液1次。当贴壁细胞融合度达到90%左右时,再进行传代(用0.25%的胰酶消化),对细胞进行计数后按1×105/mL浓度接种继续培养,用传至第3~5代的细胞进行诱导分化实验。

1.2.2 人骨髓间充质干细胞成脂诱导将3~5 代的hMSCs接种于6 孔板和培养瓶(75 cm2)中,当hMSCs细胞完全汇合之后,加入诱导培养液(0.5 mmol/LIBMX、10% FBS、100 mmol/L吲哚美新、1 μmol/L地塞米松、10 mg/L胰岛素的DMEM培养液),在诱导3 d后,用含10% FBS 和10 μg/mL胰岛素的DMEM培养液培养1 d,如此交替,诱导至21 d。用相差显微镜下观察细胞形态变化过程,并于第0、7、14、21天,进行油红O染色和细胞送检测序。

1.2.3 油红O染色染液的配制:用98 %的异丙醇溶解油红O干粉,配置成干液(油红O浓度为5 mg/mL),染色前将蒸馏水和干液以2∶3比例进行混合后静置24 h再过滤,取滤液作为新鲜染液。贴附细胞用PBS冲洗1次,用10%中性甲醛固定10 min,然后PBS漂洗,加入新鲜染液染色10 min,再用PBS冲洗后,直接镜下观察。

1.2.4 miRNAs 基因芯片检测本实验送检的细胞用TRIZOL处理,由上海烈冰生物公司进行miRNA芯片杂交。基因表达谱芯片的检测分析由总RNA的提取和鉴定、miRNA标记和miRNA芯片杂交等步骤组成,接着进行芯片扫描,最后通过Genepix Pro 6.0软件进行数据分析。

1.2.5 转录组测序(mRNA-seq)首先提取细胞样本总的RNA,根据所测RNA类别进行分离和纯化,接着将其片段化(或反转录后片段化)为测序平台所需要的长度,再连接测序的接头。利用PCR扩增,当扩增到一定丰度后上机测序,直到获得充足的序列。将所得的这些序列通过与参考基因组比对或者是从头组装以形成全基因组的转录谱,从而完成整个文库的制备工作,最后将构建好的文库通过Illumina HiSeq2000 测序系统进行测序。

1.2.6 miRNA靶基因的预测运用国际公认的模式物种靶基因预测数据库TargetScan、PicTar和miRanda对miRNA进行靶基因的预测,并取三者预测结果的交集作为靶基因,以提高预测结果的准确性和可靠性。

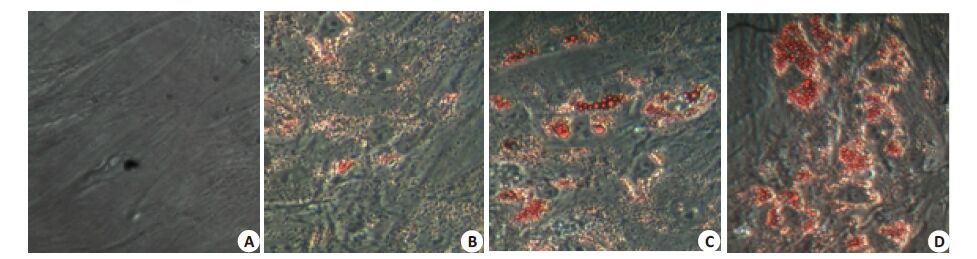

2 结果 2.1 hMSCs 诱导分化为脂肪细胞(油红O染色)MSC随着诱导时间的延长,胞内脂滴逐渐增多,细胞体积逐渐增大,由原来的长梭形变为圆形或多角形,诱导分化至21 d,绝大多数hMSCs细胞诱导分化成脂肪细胞。通过油红O染色发现许多大小不等的橙红色脂肪滴存在于脂肪细胞中(图 1)。

|

图 1 骨髓间充质干细胞分化成脂肪细胞的形态 Figure 1 Morphology of mesenchmal stem cells during adipogenic differentiation (Original magnification: ×25). A: 0 d; B: 7 d; C: 14 d;D: 21 d. |

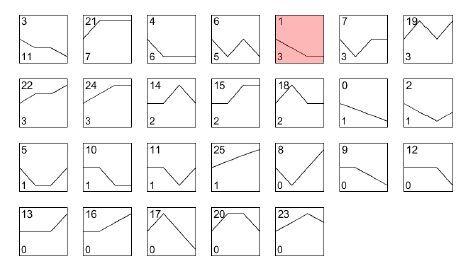

根据芯片结果,用倍数法进行差异miRNA筛选,得到各个时间点相对于起始时间点表达量变化差异显著的miRNA,筛选标准为:Fold Change>2 或FoldChange <0.5,共得到3 组差异基因:AD 7 d 和hMSCs(0 d)、AD 14 d和hMSCs(0 d)、AD 21 d和hMSCs(0 d),并集56个差异miRNA。将3组差异miRNA的并集结果在各个时间点相对于起始时间点的表达值变化情况进行统计。对差异miRNA 4个时间点的表达值变化趋势进行计算,共得到26种不同的动态变化趋势(图 2)。

|

图 2 成脂-miRNA/趋势总图 Figure 2 Dynamic changes of the differentially expressed miRNAs during adiopogenic differentiation of hMSCs. A total of 26 variation patterns of the differentially expressed miRNAs were identified. In each box, the number at the upper left corner indicates the type of variation tendency, and the number at the lower left corner indicates the number of genes that have such a variation tendency. |

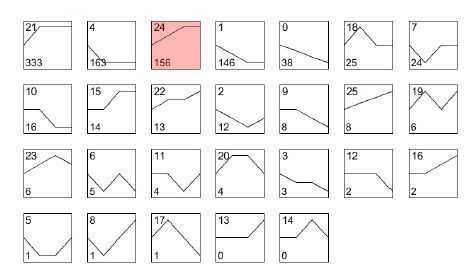

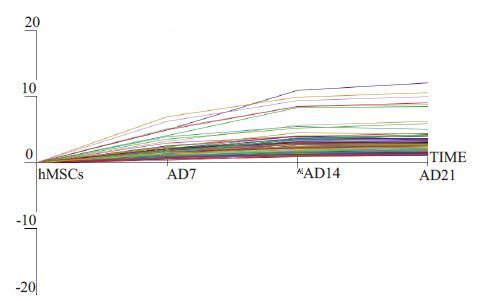

根据测序的结果用DEG-Seq进行差异基因筛选,得到各个时间点相对于起始时间点表达量变化差异显著的基因,筛选标准为:Fold Change>2,P value<0.05,FDR<0.05或Fold Change<0.5,P value<0.05,FDR<0.05,共得到3组差异基因:AD 7 d和hMSCs(0 d)、AD 14 d和hMSCs(0 d)、AD 21 d和hMSCs(0 d),并集1001个差异基因。将3组差异基因并集结果在各个时间点相对于起始时间点的表达值变化情况进行统计。对并集基因4个时间点的表达值变化趋势进行计算,共得到26种不同的动态变化趋势(图 3)。

|

图 3 成脂-mRNA/趋势总图 Figure 3 Patterns of dynamic changes of the differentially expressed mRNAs during adiopogenic differentiation of hMSCs. In each box, the number at the upper left corner indicates the type of variation tendency, and the number at the lower left corner indicates the number of genes that have such a variation tendency. |

运用国际公认的模式物种靶基因预测数据库TargetScan、PicTar和miRanda对miRNA进行靶基因的预测。根据miRNA预测得到的靶基因,以此为契合点,找到miRNA与mRNA差异表达情况相反的调控关系,即miRNA表达趋势与对应的靶基因表达趋势完全相反(根据趋势类型编号的编号原则,两类趋势编号相加为25则趋势类型完全相反,如:图 2和图 3中粉红色框趋势编号),从而聚焦到具有研究价值的miRNA与mRNA相互调控关系。

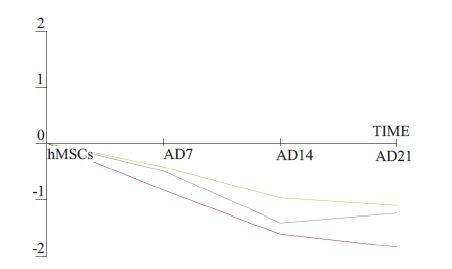

我们通过筛选获得hsa-miR-140-5p在成脂分化中的表达趋势为编号1(图 4),而通过数据库预测到其候选靶基因LIFR在成脂分化中的表达趋势为编号24(图 5)。

|

图 4 成脂-miRNA/趋势1(包括hsa-miR-140-5p在内的3个microRNA) Figure 4 Variation patterns of 3 differentially expressed miRNAs including hsa-miR-140-5p during adiopogenic differentiation of hMSCs. |

|

图 5 成脂-mRNA/趋势 Figure 5 Variation patterns of 156 differentially expressed mRNAs including LIFR during adiopogenic differentiation of hMSCs. |

本研究的miRNA 基因芯片分析结果显示,miR-140-5p(hsa-miR-140-5p)在hMSCs成脂分化过程中表达具有显著差异,且表达量呈逐渐下降趋势。已有文献报道[12-13],miR-140-5p通过作用多个不同靶基因分别抑制舌鳞状癌细胞的侵袭和转移,以及肝癌细胞的增殖和转移;参与髓鞘的形成和肥胖症的发生[14-15];调控软骨细胞的分化[16],而涉及调控hMSCs成脂分化的机制研究甚少。尽管如此,已有一篇文献报道了miR-140-5p通过靶向作用转化生长因子-β受体1(Transforminggrowth factor-β receptor 1,TGFBR1)调控成脂分化(以前脂肪细胞3T3-L1为研究对象)[17],这从侧面有力的证实了miRNA-140-5p 调控hMSCs 成脂分化的可能性。脂分化的过程中有多个miRNAs差异表达,它们通过改变细胞增殖(miR-24、miR-31、the miR-17-92 cluster)[18-19]、抑制wnt 信号通路(miR-8)[20]或影响PPARγ的表达(miR-27、miR-130)[21-23]全面参与调控成脂分化。可见miRNAs是调控hMSCs成脂分化的重要调节因子,筛选出更具潜在研究价值的miRNA是进一步研究的关键所在。miR-140-5p在成脂分化中的差异表达提示其通过靶向作用参与调节hMSCs成脂定向分化的机制值得深入研究。

在miRNAs研究基础上,针对hMSCs成脂分化过程运用Illumina HiSeq 2000 平台实施转录组测序(mRNA-seq),并将miRNA与mRNA的表达趋势进行关联分析,聚焦具有研究价值的miRNA与mRNA相互调控关系,我们发现白血病抑制因子受体(LIFR)在成脂分化中表达量呈逐渐升高趋势,而上述miR-140-5p表达量呈逐渐下降的趋势,二者呈现负调控的对应关系。同时经三个靶基因预测数据库预测,LIFR 为miR-140-5p 共有的靶基因,因此,LIFR 满足miR-140-5p候选靶基因的基本要求。

LIFR属造血细胞因子受体超家族成员[24-25],作为受体除了与LIF结合外,还可以和多种细胞因子,如抑癌蛋白M、睫状神经营养因子和心肌营养素-1等结合继而启动下游各种信号通路[26-28]。可见,LIFR是链接细胞因子(配体)和信号通路之间的枢纽,起着至关重要的作用。在本研究中我们发现LIFR在hMSCs成脂分化中表达逐渐升高,提示LIFR与成脂分化密切相关。有文献报道[29]在3T3-L1细胞成脂分化中LIFR表达也升高,且具有促进成脂分化功能。这也间接地支撑了LIFR作为miR-140-5p靶基因的可行性和重要性。

综上所述,本研究应用miRNA芯片结合转录组测序(mRNA-seq),并将miRNA与mRNA的表达趋势进行关联分析,聚焦具有研究价值的miRNA与mRNA相互调控关系,同时经3 个靶基因预测数据库预测miRNA 靶基因。最终筛选出具有潜在研究价值的miR-140-5p 及其靶基因LIFR,为miRNA-140-5p 靶向作用LIFR调控hMSCs成脂分化的后续深入研究提供了可靠依据。

| [1] | Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Science, 1999, 284 (5411): 143-7. DOI: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. |

| [2] | Arinzeh TL. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone repair: preclinical studies and potential orthopedic applications[J]. Foot Ankle Clin, 2005, 10 (4): 651-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.06.004. |

| [3] | Barry F, Boynton RE, Liu B, et al. Chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow: differentiationdependent gene expression of matrix components[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2001, 268 (2): 189-200. DOI: 10.1006/excr.2001.5278. |

| [4] | Helder MN, Knippenberg M, Klein-Nulend J, et al. Stem cells from adipose tissue allow challenging new concepts for regenerative medicine[J]. Tissue Eng, 2007, 13 (8): 1799-808. DOI: 10.1089/ten.2006.0165. |

| [5] | Rosen C, Karsenty G, Macdougald O. Foreword: interactions between bone and adipose tissue and metabolism[J]. Bone, 2012, 50 (2): 429. DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.006. |

| [6] | Scheideler M, Elabd C, Zaragosi LE, et al. Comparative transcriptomics of human multipotent stem cells during adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis[J]. BMC Genomics, 2008, 9 : 340. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-340. |

| [7] | Huang C, Gou S, Wang L, et al. MicroRNAs and peroxisome Proliferator-Activated receptors governing the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther, 2016, 11 (3): 197-207. DOI: 10.2174/1574888X10666150528144517. |

| [8] | Fanini F, Fabbri M. MicroRNAs and Cancer resistance: A new molecular plot[J]. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2016, 99 (5): 485-93. DOI: 10.1002/cpt.v99.5. |

| [9] | Garo LP, Murugaiyan G. Contribution of MicroRNAs to autoimmune diseases[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2016, 73 (10): 2041-51. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-016-2167-4. |

| [10] | Lee S, Choi E, Cha MJ, et al. Impact of miRNAs on cardiovascular aging[J]. J Geriatr Cardiol, 2015, 12 (5): 569-74. |

| [11] | Pino AM, Rosen CJ, Rodríguez JP. In osteoporosis, differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) improves bone marrow adipogenesis[J]. Biol Res, 2012, 45 (3): 279-87. DOI: 10.4067/S0716-97602012000300009. |

| [12] | Kai Y, Peng W, Ling W, et al. Reciprocal effects between microRNA-140-5p and Adam10 suppress migration and invasion of human tongue cancer cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 448 (3): 308-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.032. |

| [13] | Yang H, Fang F, Chang R, et al. MicroRNA-140-5p suppresses tumor growth and metastasis by targeting transforming growth factor β receptor 1 and fibroblast growth factor 9 in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 58 (1): 205-17. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26315. |

| [14] | Viader A, Chang LW, Fahrner T, et al. MicroRNAs modulate Schwann cell response to nerve injury by reinforcing transcriptional silencing of dedifferentiation-related genes[J]. J Neurosci, 2011, 31 (48): 17358-69. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-11.2011. |

| [15] | Ortega FJ, Mercader JM, Catalán V, et al. Targeting the circulating microRNA signature of obesity[J]. Clin Chem, 2013, 59 (5): 781-92. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.195776. |

| [16] | Swingler TE, Wheeler G, Carmont V, et al. The expression and function of microRNAs in chondrogenesis and osteoarthritis[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64 (6): 1909-19. DOI: 10.1002/art.v64.6. |

| [17] | Zhang X, Chang A, Li Y, et al. miR-140-5p regulates adipocyte differentiation by targeting transforming growth factor-β signaling[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5 (2): 18118. |

| [18] | Sun F, Wang J, Pan Q, et al. Characterization of function and regulation of miR-24-1 and miR-31[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2009, 380 (3): 660-5. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.161. |

| [19] | Kennell JA, Gerin I, Macdougald OA, et al. The microRNA miR-8 is a conserved negative regulator of Wnt signaling[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105 (40): 15417-22. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0807763105. |

| [20] | Wang Q, Li YC, Wang J, et al. miR-17-92 cluster accelerates adipocyte differentiation by negatively regulating tumor-suppressor Rb2/p130[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105 (8): 2889-94. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0800178105. |

| [21] | Lee EK, Lee MJ, Abdelmohsen K, et al. miR-130 suppresses adipogenesis by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression[J]. Mol Cell Biol, 2011, 31 (4): 626-38. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.00894-10. |

| [22] | Kim SY, Kim AY, Lee HW, et al. miR-27a is a negative regulator of adipocyte differentiation via suppressing PPAR gamma expression[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2010, 392 (3): 323-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.012. |

| [23] | Karbiener M, Fischer C, Nowitsch S, et al. microRNA miR-27b impairs human adipocyte differentiation and targets PPARgamma[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2009, 390 (2): 247-51. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.098. |

| [24] | Pan W, Cain C, Yu Y, et al. Receptor-mediated transport of LIF across blood-spinal cord barrier is upregulated after spinal cord injury[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 2006, 174 (1/2): 119-25. |

| [25] | del Valle I, Rudloff S, Carles A, et al. E-cadherin is required for the proper activation of the Lifr/Gp130 signaling pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. Development, 2013, 140 (8): 1684-92. DOI: 10.1242/dev.088690. |

| [26] | Natesh K, Bhosale D, Desai A, et al. Oncostatin-M differentially regulates mesenchymal and proneural signature genes in gliomas via STAT3 signaling[J]. Neoplasia, 2015, 17 (2): 225-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.neo.2015.01.001. |

| [27] | Wagener EM, Aurich M, Aparicio-Siegmund S, et al. The amino acid exchange R28E in ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) abrogates interleukin-6 receptor-dependent but retains CNTF receptor-dependent signaling via glycoprotein 130 (gp130)/ leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR)[J]. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289 (26): 18442-50. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M114.568857. |

| [28] | Plun-Favreau H, Perret D, Diveu C, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), cardiotrophin-1, and oncostatin M share structural binding determinants in the immunoglobulin-like domain of LIF receptor[J]. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278 (29): 27169-79. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M303168200. |

| [29] | White UA, Stephens JM. Neuropoietin activates STAT3 Independent of LIFR activation in adipocytes[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2010, 395 (1): 48-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.132. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37