2. 华北理工大学 基础医学院病理教研室, 河北 唐山 063000

2. Department of Pathology, College of Basic Medicine, North China University of Science and Technology, Tangshan 063000, China

双膦酸盐相关颌骨坏死(BRONJ)是双膦酸盐类药物的严重临床并发症[1-3]。BRONJ常发生于多发性骨髓瘤等恶性肿瘤患者,而这些患者在接受双膦酸盐治疗的同时,往往同时接受其他抗肿瘤、抗血管生成及免疫调节剂等药物的治疗。那么这些药物的应用是否会影响双膦酸盐诱发的颌骨坏死,其作用机制如何?目前尚不清楚。沙利度胺(ThD)作为免疫调节剂,具有明显的抗血管生成作用,也常和双膦酸盐一起联合用于上述肿瘤的治疗[4]。本研究旨在应用唑来膦酸建立BRONJ动物模型的基础上,加用ThD,来探讨其对BRONJ的影响及作用机制,为寻找BRONJ有效防治手段提供实验依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 实验动物采用7~8 周SPF 级雌性SpragueDawley大鼠36只,体质量220±20 g,购于北京维通利华,所有大鼠均饲养在教研室专设的动物房内。

1.1.2 主要试剂唑来膦酸(Sigma-Aldrich);沙利度胺(湖北大仝生工);CD31 抗体[1∶200,北京博奥森(bs-0468R)];TUNEL(Terminal-deoxynucleoitidylTransferase Mediated Nick End Labeling)试剂盒(Roche);乙二胺四乙酸(上海化学试剂公司)。

1.2 实验分组及处理将36只SD大鼠,随机分成3组:A组为对照组,腹腔注射生理盐水,5 次/周;B 组腹腔注射唑来膦酸(ZOL),0.125 mg/kg,2次/周;C组应用ZOL的同时,皮下注射沙利度胺(ThD),100 mg/kg,5次/周。用药3周后,拔除大鼠左上颌第1磨牙;继续用药。

拔牙后第4、8周末,分2批处死大鼠,切取上颌骨,多聚甲醛固定,乙二胺四乙酸脱钙,制作5 μm石蜡切片。每个动物随机选取3张不连续切片用于组织学分析。定量检测是在拔牙创周1 mm内毗邻骨组织中进行,计算3张切片的均值作为该动物的定量参数。

1.3 颌骨坏死组织学评价切片脱蜡,苏木素-伊红染色。定量分析包括:骨陷窝密度(BLD,个/mm2),指单位面积内骨陷窝数目;空骨陷窝百分比(PEL,%),指骨组织中空骨陷窝占骨陷窝总数的百分比;死骨面积(ADB,mm2),指骨组织中死骨区域所占的总面积。死骨评判参考文献[5]并进行了改进:即面积超过3000 μm2、空骨陷窝比≥66%的区域,被定义为死骨。BLD、PEL的测量是在400倍镜下每张切片上随机选取3个不重复视野进行评价。

1.4 微血管密度检测采用免疫组织化学方法进行检测。一抗为兔抗鼠CD31抗体(1∶200),二抗为生物素化的羊抗兔IgG;苏木素复染,二氨基联苯胺(DAB)显色。微血管密度(MVD,个/mm2)测量参考Weidner 对肿瘤微血管密度的评价方法[6],并进行了改良:200倍镜下在拔牙创周毗邻骨组织中随机选取3个视野,行微血管计数并取平均值。微血管定义为边界清楚呈棕染的内皮细胞巢团或是管壁无平滑肌层且管径小于50 μm的血管。

1.5 细胞凋亡检测按TUNEL试剂盒操作步骤进行。所用dUTP 和辣根过氧化酶均由荧光素标记。在TUNEL反应混合液处理后及DAB显色前,将切片置于荧光显微镜下观察。200倍镜下每张切片随机选取3个不重复视野,计算凋亡细胞(绿色)数,取平均值。

1.6 数据处理数据以均数±标准差表示。用SPSS 13.0统计软件对数据进行单因素方差分析,样本间多重比较采用LSD法;检验水准为双侧α=0.05。

2 结果 2.1 大体标本观察拔牙后4、8周,A组标本拔牙创愈合良好,粘膜完整,无死骨裸露;B、C组拔牙创也基本愈合,无裸露死骨,但部分标本粘膜表面有较小的瘘管(图 1)。

|

图 1 拔牙后8周拔牙创大体标本观察 Figure 1 Observation of specimens at week 8 after teeth extraction. A: Group A; B: Group B; C: Group C. Small fistulas were observed ingroups B and C (Black arrow). |

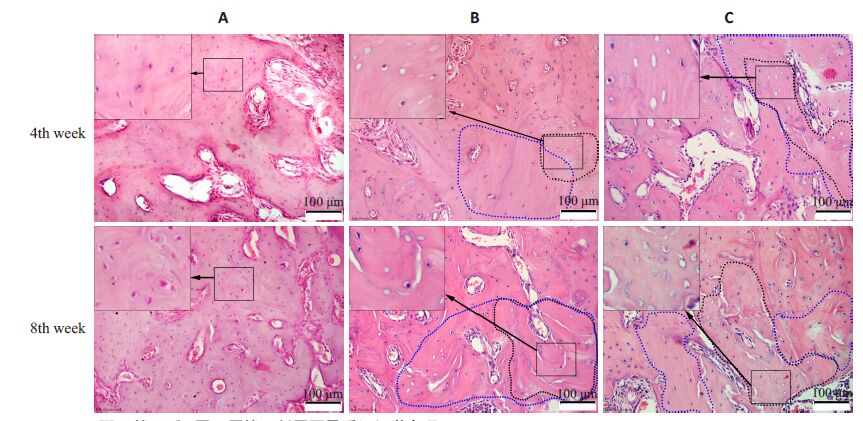

拔牙后4周,3组拔牙窝内可见新生骨组织,均无死骨形成。B组拔牙窝两侧及基底部毗邻骨组织内可见较多的空骨陷窝,有些区域空骨陷窝连接成片,为死骨;部分骨陷窝内骨细胞虽未消失,但细胞核呈固缩状态。死骨及邻近骨组织内,骨陷窝分布稀疏,骨陷窝数目较少,这些区域骨沉积线染色较深,走形紊乱。C组拔牙窝周毗邻骨组织内空骨陷窝及死骨情况较B组更为显著。而在A组,拔牙窝周毗邻骨组织内骨细胞分布正常,空骨陷窝较少,骨沉积线分布规则,未见死骨(图 2)。

|

图 2 拔牙后4周、8周拔牙创周围骨质组织学表现 Figure 2 Histological examination of the peri-socket areas at week 4 and week 8 after tooth extraction (HEstaining,original magnification: ×200). In each figure,the insert on the top left shows the magnified image ofthe boxed area. The areas encircled by blue dashed lines indicate areas with less bone lacunae,and the areasencircled by black dashed line indicate the dead bone. |

拔牙后8周(图 2),B组、C组骨基质内骨陷窝分布稀疏,可见较多的空骨陷窝和小片死骨,较4周时明显增多。A组则骨细胞分布正常,空骨陷窝较少,无死骨形成,与4周时相似。

定量分析见表 1。拔牙后4、8周,BLD A组最高,B组次之,C组最低(P<0.01)。PEL及ADB则是C组最高,B组次之,A组最低(P<0.01)。与4周比较,8周时B组、C组BLD显著降低(P<0.01),而PEL、ADB则显著增加(P<0.01)。上述结果提示,ZOL可以诱发骨细胞死亡,并引起骨坏死,而ThD则可进一步加重ZOL的上述作用。

| 表 1 拔牙后4周、8周3组BLD、PEL、ADB比较 Table 1 Comparison of BLD,PEL and ADB among the 3 groups at week 4 and week 8 after tooth extraction (Mean±SD,n=6) |

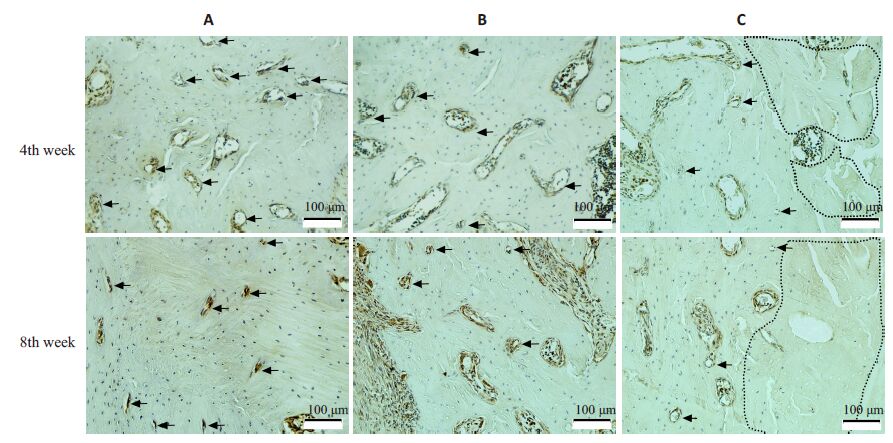

拔牙后4、8周,3组标本骨组织内均有阳性着色(棕色)微血管,但血管数目及类型有明显区别。A组微血管较多,除较大微血管外,还存在许多直径<10 μm的毛细血管及内皮细胞巢团(图 3,A组);而B组、C组死骨及周围区域微血管较少,毛细血管更少;8 周与4 周相比较,毛细血管数进一步减少(图 3B,C组);

|

图 3 拔牙后4周、8周拔牙创周围微血管检测 Figure 3 Detection of microvessels at peri-socket areas at week 4 and week 8 after tooth extraction(Iimmunohistochemistry with CD31 antibody,original magnification: × 200). The areas encircled by black dashedlines indicate the dead bone,and black arrows indicate microvessels. |

定量分析见表 2。拔牙后4周、8周,微血管密度A组最高,B组次之,C组较少。与A组比较,B组、C组微血管密度在4 周时分别减少了25.87%和55.27%(P<0.01),在8 周时分别减少了45.62%和72.84%(P<0.01)。8周与4周相比,B组、C组微血管密度则进一步减少(P<0.01)。上述结果提示,ZOL可显著抑制骨内微血管生成,而ThD则可进一步加重微血管生成障碍。

| 表 2 拔牙后4、8周三组微血管密度比较 Table 2 Comparison of microvessel density among the 3 groupsat week 4 and week 8 after tooh extraction (Mean±SD,n=6) |

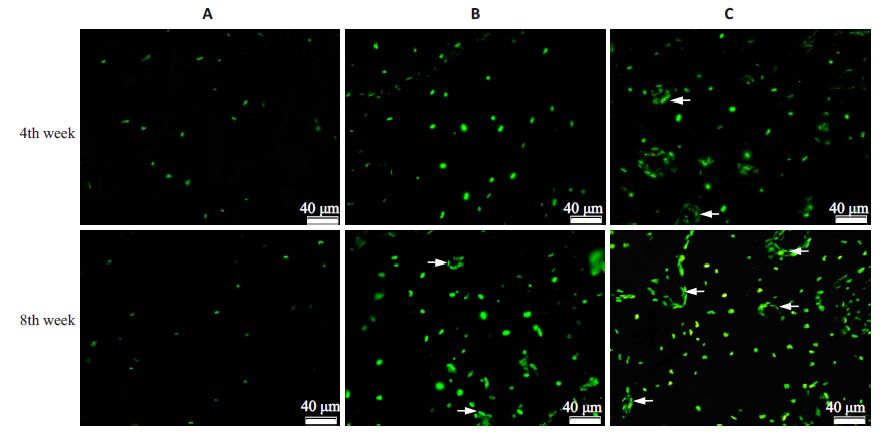

在4周、8周时(图 4,表 3),A组骨组织内细胞凋亡较少,荧光染色较浅;B组凋亡细胞较多,荧光较强,且在8周时可见血管内皮细胞凋亡现象;C组则有更多的骨细胞及血管内皮细胞发生凋亡。3组比较,4周时B组、C 组细胞凋亡数较A 组分别增加了54.80%和87.89%(P<0.01),而8 周时则分别增加了208.08%和250.58%(P<0.01)。以上结果提示,ZOL可诱发骨细胞及血管内皮细胞发生凋亡,而ThD则会进一步加重细胞凋亡现象。

|

图 4 拔牙后4周、8周拔牙创周围骨质细胞凋亡检测 Figure 4 Detection of apoptotic cells at peri-socket areas at week 4 and week 8 after tooth extraction (TUNEL assay,original magnification: ×200). More apoptotic bone cells and vascular endothelial cells (white arrows) were observedin groups B and C than in group A. |

| 表 3 拔牙后4、8周3组细胞凋亡计数比较 Table 3 Comparison of apoptotic cells among 3 groups at week4 and week 8 after tooth extraction (Mean±SD,n=6) |

BRONJ是双膦酸盐类药物临床应用最主要的并发症,严重影响患者的生活质量[1-2, 7]。针对BRONJ,国内外学者开展了广泛的临床研究工作,总结了其临床分型,规范了其治疗措施,同时,在许多动物身上成功地建立了BRONJ 动物模型[5, 8-9]。本研究通过系统应用ZOL,配合牙齿拔除术,建立大鼠颌骨坏死模型,为BRONJ发病机制的研究提供实验平台。结果表明,B组(ZOL处理组)大鼠拔牙创周围出现了成片的死骨区域,其内骨陷窝空虚,骨细胞消失,且这种现象持续长达8周,提示BRONJ动物模型是成功的。

ThD曾作为镇静、催眠及妊娠呕吐的治疗药物,但因其对血管生成抑制诱发新生儿畸形而被停用[10]。近年来,ThD被尝试用于一些肿瘤的临床治疗[10],获得了较好的效果。在这些肿瘤的治疗中,常常面临ThD和双膦酸盐类药物联合用药。ThD是否会影响双膦酸盐诱发的颌骨坏死(BRONJ),其作用机制如何?目前尚不清楚。本研究发现,加用ThD的C组拔牙窝周围骨质空骨陷窝比例、死骨面积均较单纯应用ZOL的B组显著增加,从而证实ThD的应用会加重ZOL诱发的颌骨坏死。

研究发现,ThD可显著降低多发性骨髓瘤患者骨髓内微血管密度[11],并可抑制人脐静脉内皮细胞的生长。ThD可通过激活中性神经膦脂酶,促进神经酰胺生成,来抑制血管内皮细胞表面VEGF受体,实现对血管生成的抑制[12]。本研究中,加用ThD的C组拔牙窝周围骨质内微血管密度显著降低。结果提示,ThD可显著抑制拔牙创周围骨质内微血管的生成。由于微血管生成抑制可造成局部骨质营养供应下降,成骨细胞、破骨细胞活性降低,局部骨代谢障碍,从而使这些区域更容易发生骨坏死,因而ThD对微血管生成的抑制可能是其加重ZOL诱发颌骨坏死的重要原因。

国内外学者针对BRONJ提出了多种致病学说,如破骨细胞抑制,骨转换降低[13]、上皮细胞毒性[14]、血管生成抑制等[15]。然而,上述学说在BRONJ致病机制中的作用尚无定论。帕米膦酸也可使大鼠颌骨坏死区血管数目显著减少[15]。ZOL可直接调节血管生成细胞因子的释放、抑制细胞因子与其受体结合等发挥抗血管形成作用,降低血清中新生血管形成的细胞因子VEGF、bFGF、MMP-1、MMP-2、IL 的表达[18],抑制小G蛋白翻译后修饰,阻断VEGF-VEGFR-丝裂原活化蛋白激酶-蛋白激酶B信号通路[19]。在体外,诱导内皮祖细胞和内皮细胞的分化和凋亡,可显著抑制内皮细胞增殖、黏附、迁移及毛细血管样结构生成[16-17]。ZOL不仅抑制内皮祖细胞分化和小管样形成,阳止血管发生[20-21],而且可以抑制血管内皮细胞的增殖、黏附和迁移能力,干扰血管生成[21]。本研究中,应用ZOL的B组微血管密度较A组显著降低,在拔牙后4、8周2个时间点,微血管密度分别减少了25.87%和45.62%,同时,B组微血管内皮在8周时也出现了细胞凋亡现象。以上结果提示,ZOL不仅可以直接作用于生血管形成的细胞因子,而且可以通过作用于内皮细胞显著抑制颌骨内微血管生成,造成微血管血循环障碍。因此推测ZOL对微血管的影响也是诱发颌骨坏死的重要原因。

本研究另一个重要发现是骨坏死及周围区域出现骨细胞减少,骨陷窝密度降低现象。与A组比较,B组、C 组骨陷窝密度在4 周时分别降低了21.23%和28.93%,在8周时分别降低了26.04%和35.82%。分析骨陷窝密度低的原因,可能与药物对成骨细胞活性的影响有关。研究表明,ZOL可改变前成骨细胞MC3T3的活性和生物学行为,使细胞形态、碱性膦酸酶活性及Runx1及Col1基因表达异常,向骨细胞分化障碍[22]。颌骨坏死与双膦酸盐诱发的成骨细胞功能异常有关[23]。ThD在体外也可抑制成骨细胞发育,降低细胞ALP活性及基质矿化能力[7]。骨陷窝密度降低的另一个可能原因是药物对微血管生成的抑制。如上所述,ThD和ZOL在体外及体内均有明显抗微血管生成作用,而微血管障碍可致局部营养供应下降,成骨细胞活性改变,诱发骨基质形成及矿化能力异常,导致局部骨陷窝密度减低。据我们所知,该现象在国内外为首次报道。骨陷窝密度降低使局部骨组织营养代谢能力下降,这也是这些区域更易出现坏死的重要原因。

综上所述,本研究中沙利度胺和双膦酸盐的联合应用加重了唑来膦酸诱发的早期阶段颌骨坏死,而沙利度胺及唑来膦酸对颌骨坏死的作用与其对微血管生成的抑制有关。

| [1] | 黄如冰, 吴晓林, 俞娟. 双磷酸盐相关性颌骨坏死12例临床分析[J]. 中华口腔医学研究杂志:电子版,2012, 6 (4) : 353-7. |

| [2] | 彭诚, 王东. 双膦酸盐类药物治疗相关的下颌骨坏死的研究进展[J]. 医学综述,2011, 17 (8) : 1181-3. |

| [3] | Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, et al. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on bisphosphonaterelated osteonecrosis of the jaws-2009 update[J]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg,2009, 67 (5 Suppl) : 2-12. |

| [4] | Christodoulou C, Pervena A, Klouvas G, et al. Combination of bisphosphonates and antiangiogenic factors induces osteonecrosis of the jaw more frequently than bisphosphonates alone[J]. Oncology,2009, 76 (3) : 209-11. DOI: 10.1159/000201931. |

| [5] | Bi Y, Gao Y, Ehirchiou D, et al. Bisphosphonates cause osteonecrosis of the jaw-like disease in mice[J]. Am J Pathol,2010, 177 (1) : 280-90. DOI: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090592. |

| [6] | Weidner N. Current pathologic methods for measuring intratumoral microvessel density within breast carcinoma and other solid tumors[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat,1995, 36 (2) : 169-80. DOI: 10.1007/BF00666038. |

| [7] | Bolomsky A, Schreder M, Mei?ner T, et al. Immunomodulatory drugs Thalidomide and lenalidomide affect osteoblast differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells in vitro[J]. Exp Hematol,2014, 42 (7) : 516-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.03.005. |

| [8] | Cankaya AB, Erdem MA, Isler SC, et al. Use of cone-beam computerized tomography for evaluation of bisphosphonateassociated osteonecrosis of the Jaws in an experimental rat model[J]. Int J Med Sci,2011, 8 (8) : 667-72. |

| [9] | Pautke C, Kreutzer K, Weitz J, et al. Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a minipig large animal model[J]. Bone,2012, 51 (3) : 592-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.04.020. |

| [10] | Kumar S. Anderson KC. Drug insight: thalidomide as a treatment for multiple myeloma[J]. Nat Clin Pract Oncol,2005, 2 (5) : 262-70. DOI: 10.1038/ncponc0174. |

| [11] | Kumar S, Witzig TE, Dispenzieri A, et al. Effect of thalidomide therapy on bone marrow angiogenesis in multiple myeloma[J]. Leukemia,2004, 18 (3) : 624-7. DOI: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403285. |

| [12] | Yabu T, Tomimoto H, Taguchi Y, et al. Thalidomide-induced antiangiogenic action is mediated by ceramide through depletion of VEGF receptors, and is antagonized by sphingosine-1-phosphate[J]. Blood,2005, 106 (1) : 125-34. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3679. |

| [13] | Abtahi J, Agholme F, Sandberg O, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw in a rat model arises first after the bone has become exposed. No primary necrosis in unexposed bone[J]. J Oral Pathol Med,2012, 41 (6) : 494-9. DOI: 10.1111/jop.2012.41.issue-6. |

| [14] | Kim RH, Lee RS, Williams D, et al. Bisphosphonates induce senescence in normal human oral keratinocytes[J]. J Dent Res,2011, 90 (6) : 810-6. DOI: 10.1177/0022034511402995. |

| [15] | López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Martínez-Canovas A, et al. Perioperative antibiotic regimen in rats treated with pamidronate plus dexamethasone and subjected to dental extraction: a study of the changes in the Jaws[J]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg,2011, 69 (10) : 2488-93. DOI: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.059. |

| [16] | Wood J, Bonjean K, Ruetz S, et al. Novel antiangiogenic effects of the bisphosphonate compound zoledronic acid[J]. J Pharm Exp Ther,2002, 302 (3) : 1055-61. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.102.035295. |

| [17] | Fournier P, Boissier S, Filleur S, et al. Bisphosphonates inhibit angiogenesis in vitro and testosterone-stimulated vascular regrowth in the ventral prostate in castrated rats[J]. Cancer Res,2002, 62 (22) : 6538-44. |

| [18] | Santini D, Vincenzi B, Galinzzo S, et al. Repeated intermittent low. dose therapy with zoledronic acid induces all early, sustained, and long-lasting decrease of peripheral vascular endothelial growth factor levels in cancer patients[J]. Clin Cancer Res,2007, 13 (15) : 4482-6. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0551. |

| [19] | Soltau J, Zirrgiebel U, Esser N, et al. Antitumoral and antiangiogenic efficacy of bisphosphonates in vitro and in a murine RENCA model[J]. Anticancer Res,2008, 28 (2A) : 933-41. |

| [20] | Yamada J, Tsuno NH, Kitaymma J, et al. Anti-angiogenie property of zoledrenic acid by inhibition of endothelial progenitor cell differentiation[J]. J Surg Res,2009, 151 (1) : 115-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.01.031. |

| [21] | Hasmim M, Bider M, Ruegg C. Zoledronate inhibits endothelial cell adhesion. migration and survival through the suppression of multiple, prenylation-dependent signaling pathways[J] . J Thmmb Haemest, 2007, 5(1): 166-73. |

| [22] | Patntirapong S, Singhatanadgit W, Chanruangvanit C, et al. Zoledronic acid suppresses mineralization through direct cytotoxicity and osteoblast differentiation inhibition[J]. J Oral Pathol Med,2012, 41 (9) : 713-20. DOI: 10.1111/jop.2012.41.issue-9. |

| [23] | Subramanian G, Cohen HV, Quek SY. A model for the pathogenesis of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw and teriparatide's potential role in its resolution[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod,2011, 112 (6) : 744-53. DOI: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.020. |

2015, Vol. 35

2015, Vol. 35